News & Blog

Global Market for Company School Paintings (18th–19th Century British India)

Company School painting – also known as “Company style” – refers to a Indo-European style of watercolor painting that flourished in British India during the late 18th and 19th centuries . The style first emerged around the 1760s–1770s in eastern India (Murshidabad in Bengal) and soon spread to other centers of British activity such as Benares (Varanasi), Delhi, Lucknow, Madras, and Patna . Indian artists, many trained in Mughal or regional courts, adapted their traditional techniques to suit the tastes of employees of the English East India Company. The result was a “hybrid originality” blending the refined detail and vibrant color of Mughal miniature art with Western conventions of perspective and shading . These works were typically executed in watercolor on paper (and occasionally on delicate mica sheets) and ranged from small album pages to larger folios .

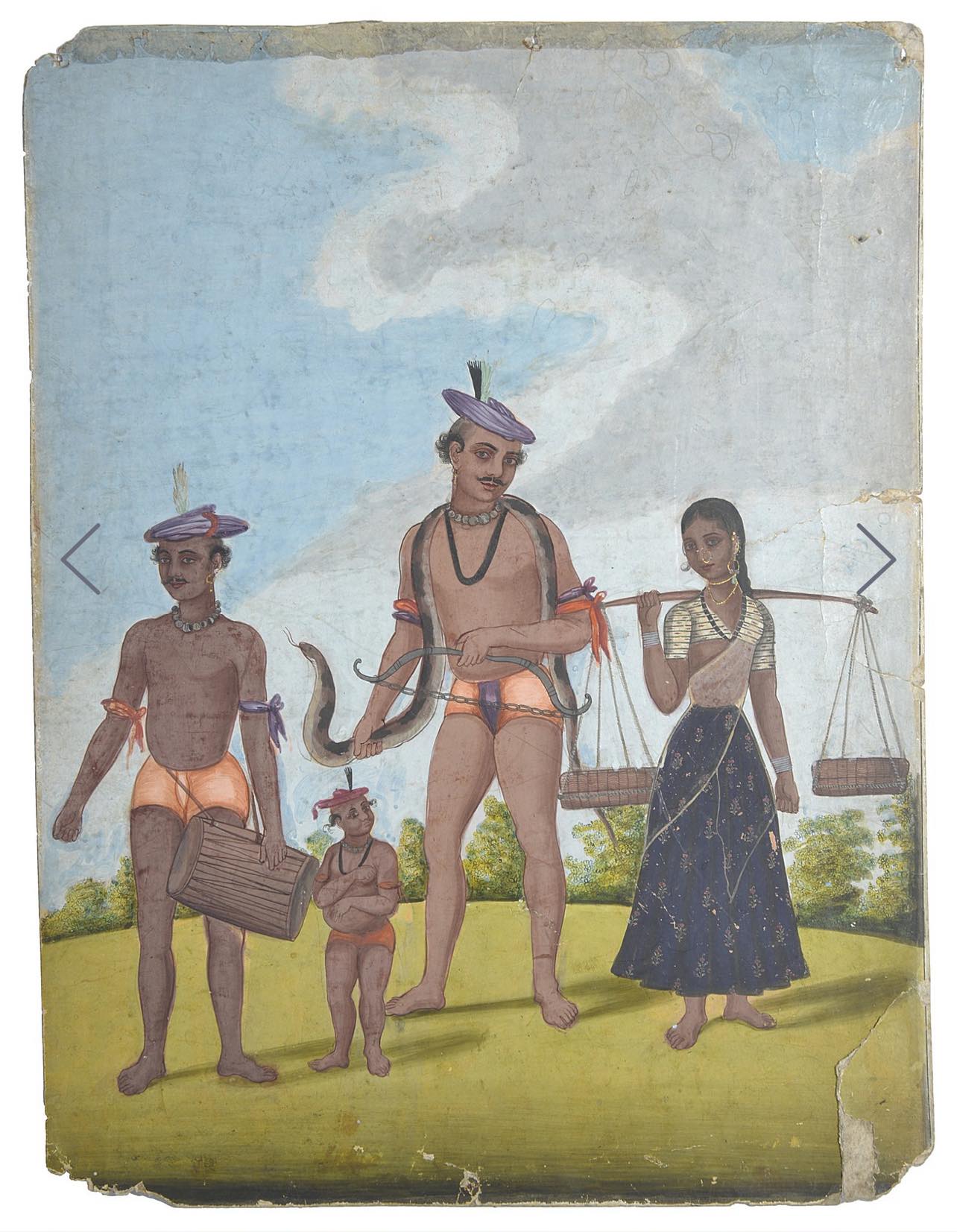

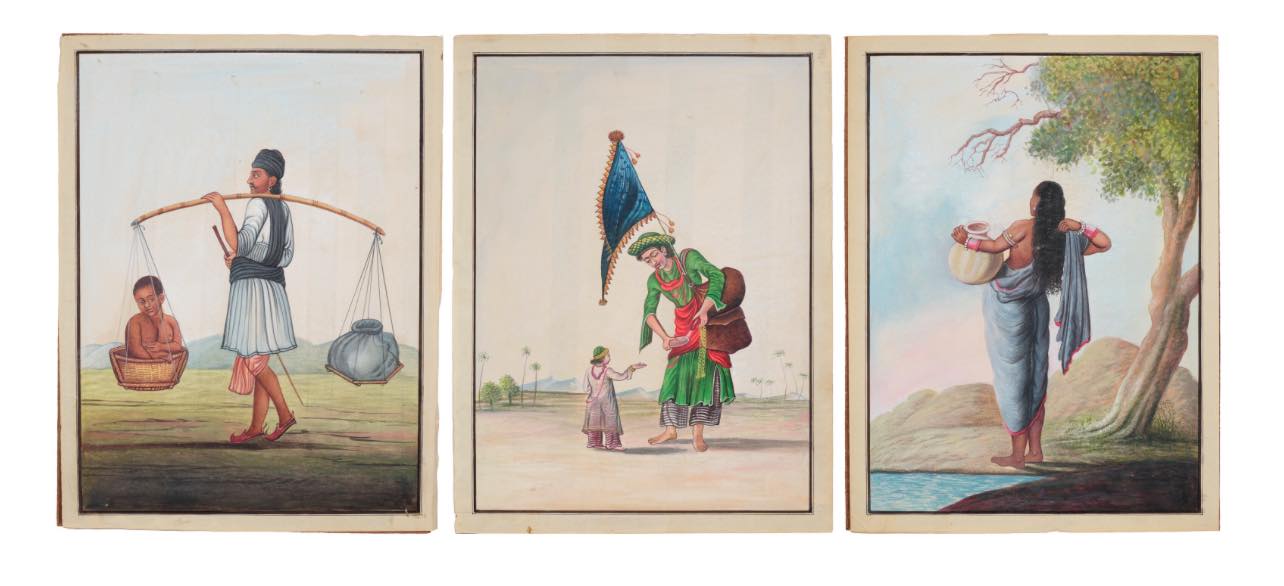

Popular subject matter in Company School art was shaped by European patron interest. Favorite themes included scenes of everyday life in India, occupations and castes, festivals and rituals, portraits of local rulers or residents, and studies of Indian flora and fauna . The “cult of the picturesque” in late Georgian Britain fueled demand for images of an exotic India, resulting in series depicting costumes, trades, monuments, and native customs . Notably, Indian painters produced brilliantly observed natural history illustrations of plants, birds, and animals that often rivaled or exceeded the quality of contemporary European scientific drawings . By the early 19th century, enterprising artists were assembling portfolios of standard subjects to sell to British officers, travelers and tourists passing through, indicating a shift from working solely on commission to a more speculative art market .

Hibiscus flower study, 19th-century Company School watercolor. Botanical subjects like this were popular commissions for East India Company patrons .

The historical context of Company School paintings is closely tied to the colonial encounter. These works were often created by Indian artists employed or patronized by East India Company officials, hence the appellation “Company” school. Albums such as those commissioned by Lady Mary Impey in Calcutta (1770s–1780s) – featuring birds and animals rendered by artists like Shaykh Zayn al-Din and Bhawani Das – or the Fraser Album commissioned in Delhi (1815–1820) by British officers James and William Fraser – featuring portraits of villagers and local nobility – exemplify the genre’s range . Such collections were brought back to Europe or passed down through families, forming the nucleus of many holdings of Company paintings in the West. Over time, however, these works were somewhat neglected by art historians, viewed as a provincial offshoot of Indian miniature art. It was only in recent decades that their importance has been re-evaluated. In 2019–2020, the Wallace Collection in London mounted Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, the first major exhibition in the UK devoted to Company School master painters . As writer-historian William Dalrymple (who curated the exhibition) observed, this genre is “only now beginning to receive its full credit” – a recognition that has helped spark new appreciation and demand in the art market.

Market Trends in the Past 15 Years

Over the last 10–15 years, the market for Company School paintings has seen a notable upswing in interest, driven by both scholarly reappraisal and collectors’ expanding taste for historical Indian art. In the early 2000s, Company paintings were often overshadowed by higher-profile categories (such as modern Indian painters or classical Indian miniatures), and many works traded privately or at minor sales for modest prices. However, the 2010s witnessed growing visibility for this niche. Blue-chip auctioneers began spotlighting Company School works in their regular Islamic and Indian art sales, and collectors recognized the genre’s unique blend of aesthetic and historical value.

A clear inflection point was the landmark dedicated sale “In an Indian Garden: The Carlton Rochell Collection of Company School Paintings” at Sotheby’s London on 27 October 2021 – the first auction devoted entirely to Company School works . The sale offered 29 lots of paintings from the Rochell collection (spanning natural history studies to architectural views) with a total pre-sale estimate of £1.7–2.5 million . The results confirmed robust demand: the auction realized approximately £3 million (about $4.2M), nearly doubling its low estimate . The top lot was “A Great Indian Fruit Bat” (a striking watercolor of a flying fox bat from the Impey Album, Calcutta circa 1778) which sparked competitive bidding and sold for £644,200 – more than twice its estimate . This price was, at the time, among the highest ever paid for a Company School painting at auction. Importantly, the sale attracted global buyers and set multiple artist records, signaling that what had once been considered a provincial curiosity had firmly entered the international collecting mainstream.

Subsequent auctions have continued this momentum. Sotheby’s and Christie’s now regularly include Company School pieces in their spring and autumn sales of South Asian or Islamic art, and dedicated single-owner sales have further cemented market confidence. In late 2023, Sotheby’s held a much-anticipated auction of The Stuart Cary Welch Collection (Part II) in London, which included several Company School masterworks with illustrious provenance. That sale “doubled its estimate, bringing in over £10 million” in total, underscoring “continued interest in pieces with distinguished provenance” . The top lot was an exceptionally important painting from the Fraser Album – an Assembly of Village Elders with William Fraser’s Munshi and Diwan (Delhi, c.1816) – which had been valued at £150,000–250,000 and ultimately sold for £952,500 (a new auction record for a Company School work) . At Christie’s in the same season, An Eye Enchanted: The Collection of Toby Falk (October 2023) featured over 150 Indian paintings including Company School examples. Bidding was vigorous for the rarest pieces; for example, a watercolor of “A Lesser Coucal on a Frangipani Branch” (1777, from the Impey collection, attributed to Shaykh Zayn al-Din) soared to £504,000, far above its £80–120k estimate . These recent sales indicate that top-tier Company paintings – especially those from famous series or artists – are achieving prices on par with important Rajput or Mughal miniatures, a scenario almost unthinkable two decades ago.

Not every Company School work commands six figures, of course. The market displays a broad pricing spectrum that has remained relatively accessible at the lower end even as headline prices rise. Many attractive but more common examples can be acquired in the £1,000–£5,000 range, and occasionally even below estimate if interest is lukewarm. For instance, two small mid-19th-century Company School watercolors of South Indian palanquin bearers and cultivators (lot in the Toby Falk collection sale) carried a £3,000–4,000 estimate but realized only £1,512 at Christie’s London (October 2023) , reflecting that lesser subjects or repetitive scenes still trade at modest levels. On the other hand, works that are fresh to the market with strong provenance and academic interest often ignite competitive bidding well above estimate. As one observer noted, there has been “a steady stream of activity at lower prices, notably for works new to market and a strong provenance, with many exceeding sensitively moderate estimates” . Overall, auction data from the past decade show value appreciation for the best Company School paintings, with record prices being re-set multiple times. The supply of high-quality material is relatively limited – largely coming from old collections being dispersed – and newly rediscovered pieces (e.g. from British country house attics or estates) tend to be eagerly snapped up by dealers and collectors. Meanwhile, mid-range works (especially those depicting popular subjects like Indian animals, trades, or monuments) have seen price growth as a broader base of buyers enters the market.

Notable Auction Results: Highs and Lows

To illustrate current market pricing, the table below highlights a range of recent auction results for Company School paintings, from record-setting highs to more affordable lows. These examples from the last few years show how subject, rarity, and provenance directly influence realized prices:

Artwork (Description)

Auction House & Date

Price Realized

Assembly of Village Elders with Fraser’s Munshi and Diwan (Delhi, c.1816, from the Fraser Album) – Master Indian artist for William Fraser

Sotheby’s London (25 Oct 2023)

£952,500

A Lesser Coucal on a Frangipani Branch (Calcutta, 1777, Impey Album) – Signed Shaykh Zayn al-Din

Christie’s London (26 Oct 2023)

£504,000

A Great Indian Fruit Bat (Flying Fox) (Calcutta, c.1778, Impey Album) – Signed Bhawani Das

Sotheby’s London (27 Oct 2021)

£644,200

“Nephelium” (Lychee) Botanical Study (Calcutta, c.1800) – Company School watercolor on paper

Christie’s London (22 Nov 2022)

£27,720

Two Company School Paintings: Palanquin Bearers & Cultivators (South India, mid-19th c.) – Small genre scenes

*Sources: Auction result data compiled from Sotheby’s and Christie’s published results ? ? ? ?.

As shown above, works with exceptional qualities have brought extraordinary prices. The Fraser Album assembly scene and Impey bird painting each fetched well into six figures, driven by their coveted provenance and subject matter (the Fraser Album and Impey Album are legendary collections) and, in the case of the bird, the attribution to a known artist. By contrast, routine or less distinctive works – such as the anonymous scenes of laborers – can sell for only a few thousand pounds. An interesting mid-market example is the botanical study of a Nephelium fruit: initially estimated at just £2,000–£3,000, it realized £27,720 ? after vigorous bidding, likely because of its scientific charm and perhaps competition between collectors of natural history art. These examples underscore that the market is selective: collectors will pay a premium for the very best or most interesting Company School pieces, while more ordinary works remain relatively affordable.

Key Valuation Factors for Company School Paintings

What makes one Company School painting worth under £2,000 and another worth over £200,000? Several key factors determine value in this collecting category:

• Subject Matter & Aesthetic Appeal: Subject is perhaps the most decisive factor. Paintings of exotic animals, birds, and botanical wonders – executed with fine detail – are highly prized, as evidenced by the Impey Album natural history pieces commanding record prices ? ?. These subjects have cross-collectible appeal (natural history enthusiasts as well as art collectors) and exemplify the technical brilliance of Company School artists. Similarly, particularly elegant or poignant depictions of Indian people and costumes can do well, especially if they have ethnographic significance or visual charm. In contrast, very commonplace subjects or repetitive workshop productions (for example, the many iterations of generic bazaar scenes or occupational types made for tourists) tend to be less valued. Genre scenes can still be desirable if they are compositionally engaging or rare views, but as the auction data shows, uninspired examples might only fetch low four figures. In short, collectors favor works that are both visually striking and culturally significant, aligning with the current appreciation for these paintings as documents of a bygone era.

• Provenance & Historical Importance: Provenance has proven to be a critical value driver for Company School works. Paintings originating from renowned commissioned albums or illustrious collections carry a cachet that translates into higher prices. For example, pieces from the Impey Album (commissioned by Sir Elijah and Lady Impey in the 1770s) or the Fraser Album (Delhi, c.1815) almost automatically command premium estimates – and often soar beyond them ? ?. These sets are well-documented in literature and museum collections, which reassures buyers of their importance and authenticity. Later provenances can also add value: a work that passed through the hands of a famous collector or was exhibited in a prominent museum exhibition will generally be more sought-after than one with obscure or dealer provenance. As Louise Broadhurst, a specialist in Islamic & Indian Art at Sotheby’s, noted, the strong results of the Welch collection sale were a “testament to the continued interest in pieces with distinguished provenance” ?. Provenance not only tells a story – linking the painting to colonial history or previous connoisseurs – but also often implies the work is a vetted “blue-chip” example of its type.

• Artist or Atelier Attribution: Many Company School paintings are unsigned and attributed only to a regional school or workshop. When a specific artist’s name can be attached – especially one of the known masters – values typically increase. Scholars have identified a few individual artists of the Company period, such as Shaykh Zayn al-Din, Bhawani Das, and Ram Das (all active in Calcutta for the Impeys), Ghulam Ali Khan (a Mughal-trained artist in Delhi, active 1810s), Sita Ram (painter of views for Lord Hastings, 1810s), and Shaikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya (Calcutta, 1830s–40s), among others. Works firmly attributed to these figures or their immediate circle are keenly collected. For instance, the signed Shaykh Zayn al-Din bird in the Toby Falk sale fetched over £500k ?, bolstered by the artist’s reputation as a master of natural history illustration. Similarly, paintings inscribed by or attributed to Ghulam Ali Khan (who worked for the Fraser family and later for Delhi kings) are very desirable. On the contrary, an equally old and attractive work but with no known artist name might fetch less simply due to the absence of that extra acclaim. That said, Company School attribution is a developing field; new research and publications (often by experts like Toby Falk, who himself catalogued many in his career) continue to draw connections that can enhance the market profile of certain pieces.

• Size and Medium: The format of a painting can affect its price. Most Company School works are small-to-medium sized watercolors on paper, a size convenient for albums. When larger works surface – for example, panoramas or multi-sheet views – they can command higher prices due to their rarity. A large, detailed architectural panorama or city view (occasionally produced in Delhi or Lucknow) might attract strong bidding from both art and history buffs. Meanwhile, paintings on mica, a specific sub-genre often depicting sets of occupations or processions, tend to be less expensive. Mica paintings (small translucent sheets) were mass-produced as souvenirs in the mid-19th century; their delicate nature means surviving examples often have paint loss or wear, and thus collectors value them more as curios. They usually trade in the hundreds to low thousands of pounds for sets, considerably less than comparable works on paper. Thus, medium and condition go hand in hand: a work on paper that has retained vibrant color will be favored over a faded or damaged one, and collectors carefully assess issues like foxing, pigment fading, or repairs when valuing a piece. Excellent condition can significantly enhance value, particularly for works on paper from over two centuries ago. For example, the vivid “A Painted Stork Eating a Snail” from the Impey series (ex-Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis collection) was noted for its fine preservation, contributing to its high estimate (£200–300k) and eventual sale to a prominent collector ?. In summary, larger, well-preserved works on paper are the ideal; anything that deviates (smaller format, on mica, or condition problems) tends to adjust the price downward.

• Historical Context & Rarity: Collectors and investors also consider how rare or important a given subject is. If a painting represents a unique view (say, an unusual scene of a specific regional festival or a now-lost monument) or a rare subject (such as an animal seldom depicted), it may achieve a premium because it fills a gap in collections. Many Company School paintings come in series (caste portraits, trades, etc.); an individual page from a common series is less rare, unless one is trying to assemble a complete set. On the other hand, a one-off work like an individual portrait of a notable figure (e.g. an Indian nobleman done in Company style) can be historically important. The market also values paintings that have academic or museum interest – for instance, if a work has been published in a seminal book or exhibited, it gains a pedigree. Conversely, if similar examples frequently appear in the market, prices may be tempered by the supply. Investors therefore look for standout pieces that combine aesthetic appeal, strong provenance, known authorship, and rarity of subject. Those works tend to appreciate the most and hold their value best over time.

Regional Demand and Collectors’ Base

The collector base for Company School paintings has become increasingly international, though historically it was centered in the UK. Given their origins, many of these paintings remained in British collections (often passed down in families of former colonial officials) and thus the UK has long been a locus of supply – and demand – for Company School art. British dealers and institutions showed interest in these works as early as the mid-20th century (the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, for example, acquired Company paintings from the Impey collection in the 1960s). Today, London remains a key hub: both Sotheby’s and Christie’s hold their major sales of Company School material in London, and a significant contingent of buyers is based in the UK or Europe. Some prominent British collectors (and occasionally Indian art foundations in the UK) actively seek out top pieces. The 2019 Forgotten Masters exhibition in London further expanded local collector awareness, and the success of dedicated sales like In an Indian Garden have proven that a solid UK collecting base exists for this genre.

At the same time, demand in the United States has grown, primarily among museums and educated private collectors. The late Stuart Cary Welch – a Harvard curator whose collection yielded many record-setting Company paintings – was American, and his holdings now dispersed at auction have gone to buyers around the globe ?. American museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York began acquiring Company paintings (often as gifts) in the late 20th century, recognizing their cultural value. Notably, several Impey Album paintings entered U.S. collections; for instance, the MET owns a dramatic rendering of a giant fruit bat similar to the one that sold for £644k ?. Even Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis had acquired an Impey painting (Stork Eating a Snail) for her personal collection ?, indicating that interest in these works among American connoisseurs dates back at least to the mid-20th century. In recent auctions, U.S.-based bidders have been active, sometimes competing fiercely for important lots (either directly or via agents). Galleries in New York and other cities occasionally handle Company School works, catering to collectors who appreciate the fusion of art and history.

Interest in India and the wider South Asian region is a more recent phenomenon. During the 19th and much of the 20th century, Company School paintings were generally exported or kept abroad, and relatively few made their way into Indian museum collections. However, in the last 10–15 years, as India’s art market has matured, a number of Indian collectors (especially those passionate about historical art or with an eye for repatriating heritage items) have started to show interest. Indian auction houses (like Saffronart in Mumbai) have occasionally offered Company paintings, though the most important pieces still tend to appear in London or New York. There is also growing institutional interest within India: exhibitions at the National Museum in New Delhi and the Victoria Memorial Hall in Kolkata have highlighted Company period art, potentially spurring local collecting. It’s worth noting that many Indian collectors remain primarily focused on modern and contemporary art, but a subset – sometimes overlapping with those who collect classical Indian miniatures – are now pursuing Company School works as part of a broader appreciation of Indian art history. Additionally, members of the Indian diaspora have been active players in this market, often purchasing at international sales to build collections that celebrate their heritage.

Beyond the UK, US, and India, collectors from other regions have also entered the fray. Notably, acquisitions by Middle Eastern buyers have been reported in top-tier sales of Indian art. For example, a prominent Qatari royal collection (Sheikh Saud Al Thani) once owned the Impey Album Great Indian Fruit Bat before it was offered by Carlton Rochell ?, and buyers from the Gulf have shown interest in Indo-Islamic art as part of broader Islamic art collecting. European collectors (in France, Germany, etc.) who have long collected Orientalist paintings and Indian miniatures are likewise drawn to Company paintings. The subject matter – whether architectural views of the Taj Mahal or studies of Indian wildlife – has broad cross-cultural appeal, which helps explain the geographically diverse bidding seen at recent auctions. Christie’s has noted bidders from Asia, North America, and the Middle East in their Indian painting sales, reflecting a truly global audience for this material.

In terms of where the strongest collector base lies today, the UK and US still lead in terms of both volume and high-end buying power, thanks to longstanding collections, specialist dealers, and institutional support in those countries. India’s collector base for Company School art, while growing, is smaller and more focused on acquiring select masterpieces (sometimes via the international sales). Nonetheless, as appreciation increases in India, we may see more competition originating from the subcontinent for marquee works – a trend already observed in the modern art sector and slowly extending to historical art. Overall, the market for Company School paintings is no longer confined to any one region; it is an international niche market with a dispersed but enthusiastic community of collectors, investors, and museums all vying for the finest pieces.

Conclusion and Market Outlook

The resurgence of interest in Company School paintings has transformed this once-overlooked corner of art history into a vibrant collectible category on the global stage. Market indicators over the past decade – including record-breaking auction results, dedicated single-owner sales, and increased scholarly attention – suggest a positive trajectory for the value and appreciation of these works. The consensus among experts is that Company School paintings are finally getting their due recognition as “great masterpieces of Indian painting” that offer a unique window into the colonial experience . As a result, many collectors now view top-quality Company paintings as long-term assets, comparable to established sectors like Mughal miniatures or Chinese export art.

Looking ahead, the market trajectory appears optimistic but will likely stratify. The best of the best – works with impeccable provenance, rarity, and visual impact – should continue to attract strong prices and even set new records. As remaining masterpieces from famed albums (Impey, Fraser, etc.) surface only rarely, when they do, wealthy collectors and institutions can be expected to drive fierce bidding competition. We have already seen prices for such pieces reach into the high six figures in sterling, and it is conceivable that the very finest example (or an entire important album) could one day break the £1 million threshold at auction, especially if two or more determined bidders (perhaps a major museum and a private collector) face off. The current world-record levels around $800k–1M could thus be tested and exceeded in coming years, given the relative scarcity of top material and the deep pockets of some collectors with an interest in South Asian art heritage.

For the broader market of more typical Company School works, steady growth is likely but may depend on the overall economic climate and collector base expansion. The pool of collectors for this niche is still relatively small compared to contemporary art or even traditional Indian modern art, but it is expanding as awareness spreads. Continued museum exhibitions and publications on Company School art (such as catalogs like Forgotten Masters) will educate new audiences and possibly inspire new collectors – including younger generations of South Asian descent looking to connect with their history through art. Regional demand could also shift upward if, for example, Indian governmental or corporate collections begin to actively acquire these works (a development that has precedent in other categories). Additionally, if more pieces emerge from obscurity – say, from British country house collections being downsized – a fresh supply of quality material could stimulate the market and provide opportunities for new buyers.

For potential investors and collectors considering Company School paintings, several pieces of advice emerge from recent market analysis:

• Focus on Quality and Rarity: It is advisable to acquire the highest-quality examples one’s budget allows. Iconic natural history subjects, well-documented album pieces, or anything with a notable inscription or artist attribution can be worth the premium, as these have shown the strongest price appreciation. Rarity of subject or type (for instance, an unusual large-format work, or an atypical subject like an important historical event) can make a piece a centerpiece of a collection and more likely to increase in value over time.

• Provenance and Documentation are Key: Seek works with good provenance records – ideally traced to a known colonial-era collection or a reputable past owner. Provenance not only adds cachet but can affect resale value and ease of sale. It’s also wise to ensure any prospective purchase comes with proper documentation (old sale catalogs, references in literature, exhibition history). These elements reinforce the artwork’s legitimacy and narrative, which the next generation of buyers will also find attractive ?.

• Be Condition-Conscious: Condition can significantly impact value, so carefully examine any work (or have a specialist condition report) to check for issues like fading, staining, or over-painting. Given the age of these paintings, some wear is expected, but well-preserved colors and details distinguish the most desirable pieces. Conservation of works on paper can be done, but overly restored pieces might be viewed less favorably by seasoned collectors. In short, a bright, well-kept painting will be easier to sell and likely appreciate more than a duller example of the same subject.

• Stay Informed on Scholarship: The field of Company School art is benefiting from ongoing research. Keeping abreast of the latest publications or expert opinions can yield insights – for example, an attribution upgrade (identifying an anonymous work as by a known artist) can dramatically enhance value. Networking with specialists, attending relevant auctions, and even consulting academic resources can give an investor a savvy edge. In some cases, one might spot undervalued works in the market that lack an obvious attribution or provenance which, with research, could be linked to a famous series (unlocking hidden value).

• Long-Term Perspective: Finally, approach this category with a medium- to long-term horizon. The market is not extremely liquid – top pieces appear infrequently, and finding the right buyer can take time – so these paintings are best considered as collectible assets to be enjoyed while they appreciate, rather than quick-flip investments. Over a 5–10 year span, the trajectory has been upward, and the cultural significance of Company School art suggests it will endure. However, tastes can evolve, so building a collection that also has personal or historical resonance (not just driven by price) will ensure satisfaction even through market fluctuations.

Company School paintings have transitioned from colonial-era curiosities to “cherished” works of fine art in their own right ?. The global market for these paintings is robust and maturing, characterized by informed collectors who value the blend of artistry and historical insight that each work provides. With strong foundations now in place – expert recognition, institutional interest, and a growing collector base – the outlook remains positive. Barring any severe economic downturns, we can expect collector enthusiasm to sustain or increase prices, especially at the high end. For collectors and investors, this niche offers the rewarding opportunity to own a tangible piece of eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Indian history, one that is not only aesthetically captivating but also increasingly appreciated as a “true collaboration” between India and Europe ?. As new generations discover these Indo-European works, the Company School’s legacy seems poised to flourish further, both in scholarship and in the art marketplace – making it a fascinating sector to watch (and participate in) in the years to come.