News & Blog

Masterpiece in Bengal’s Academic Realist Tradition

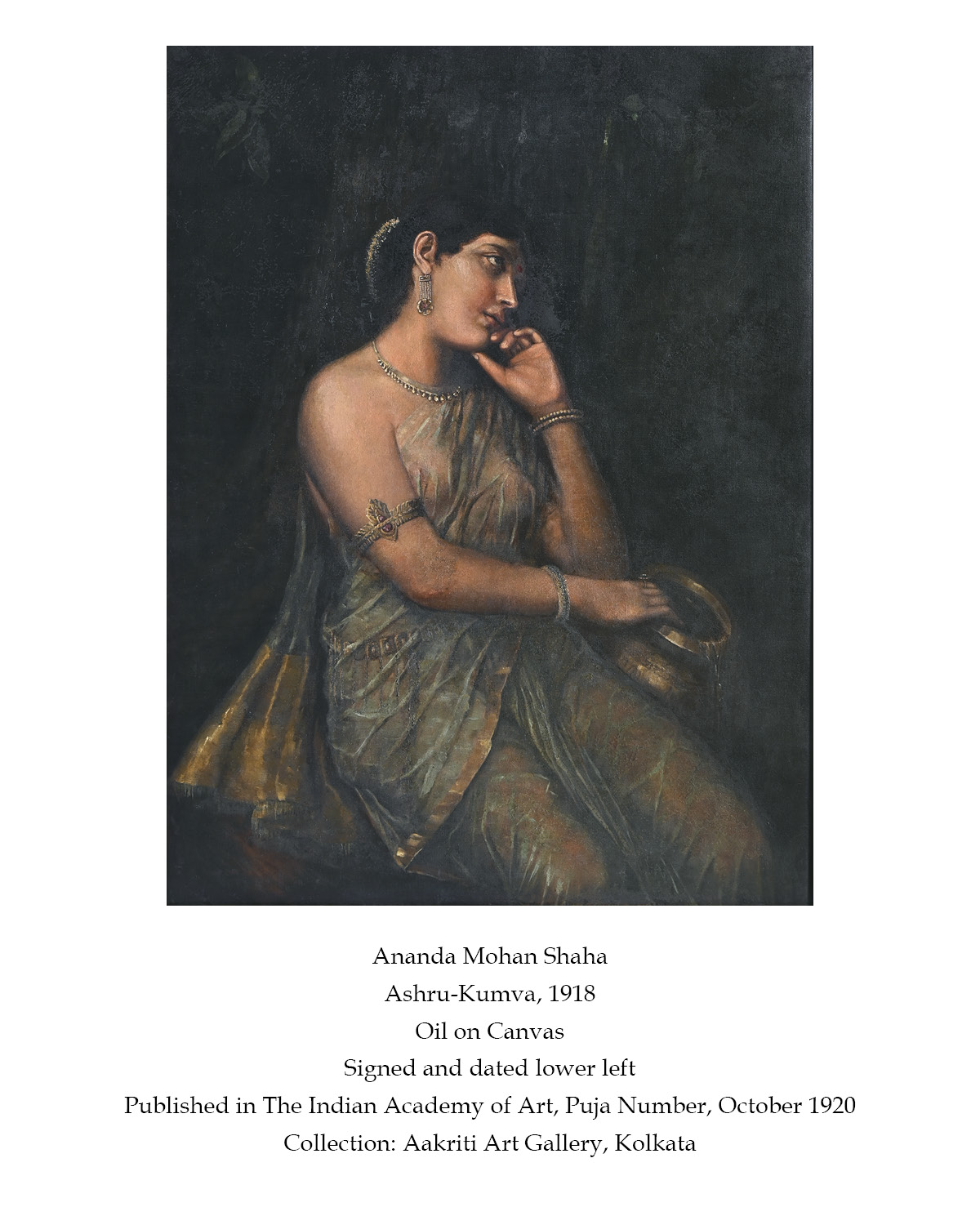

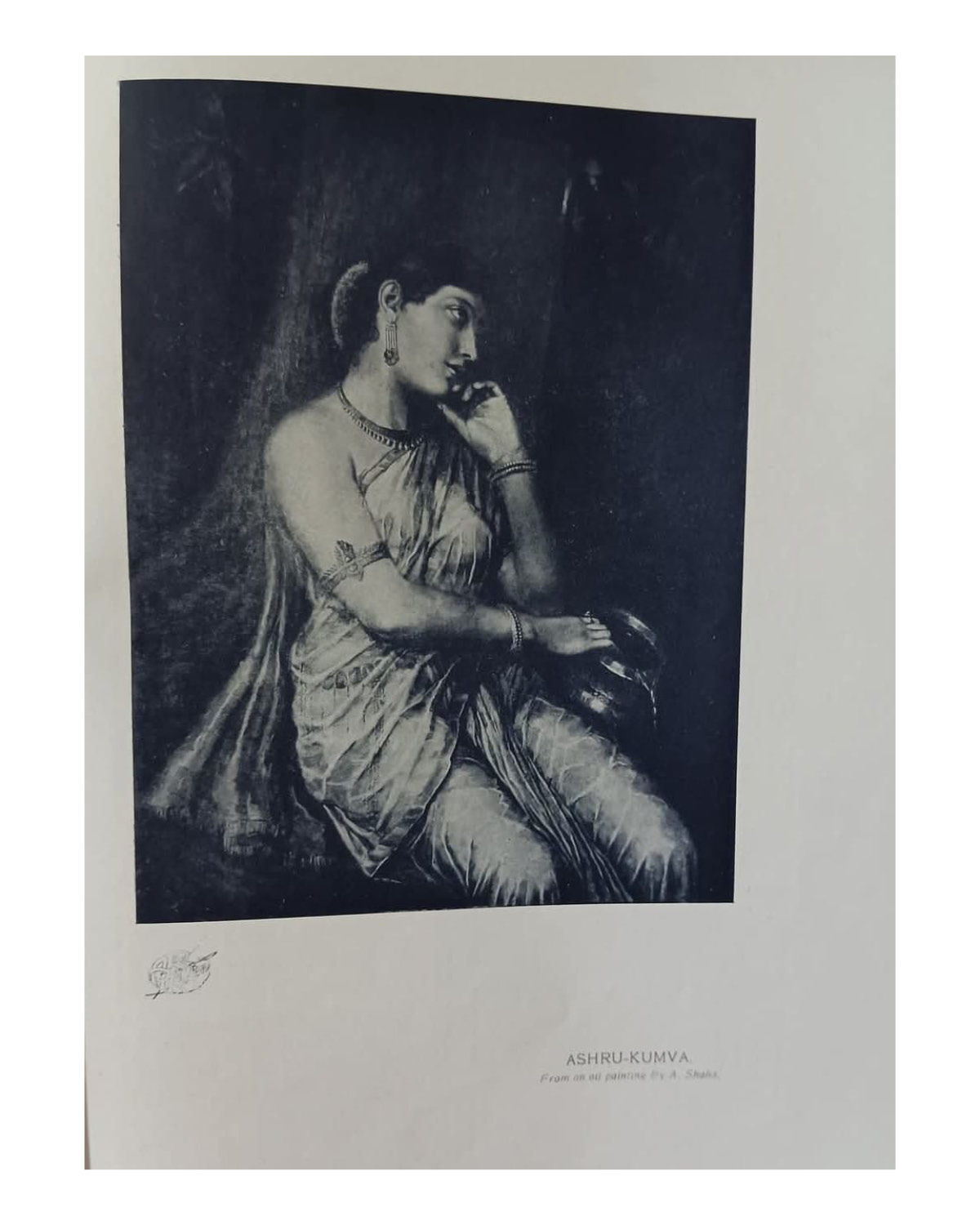

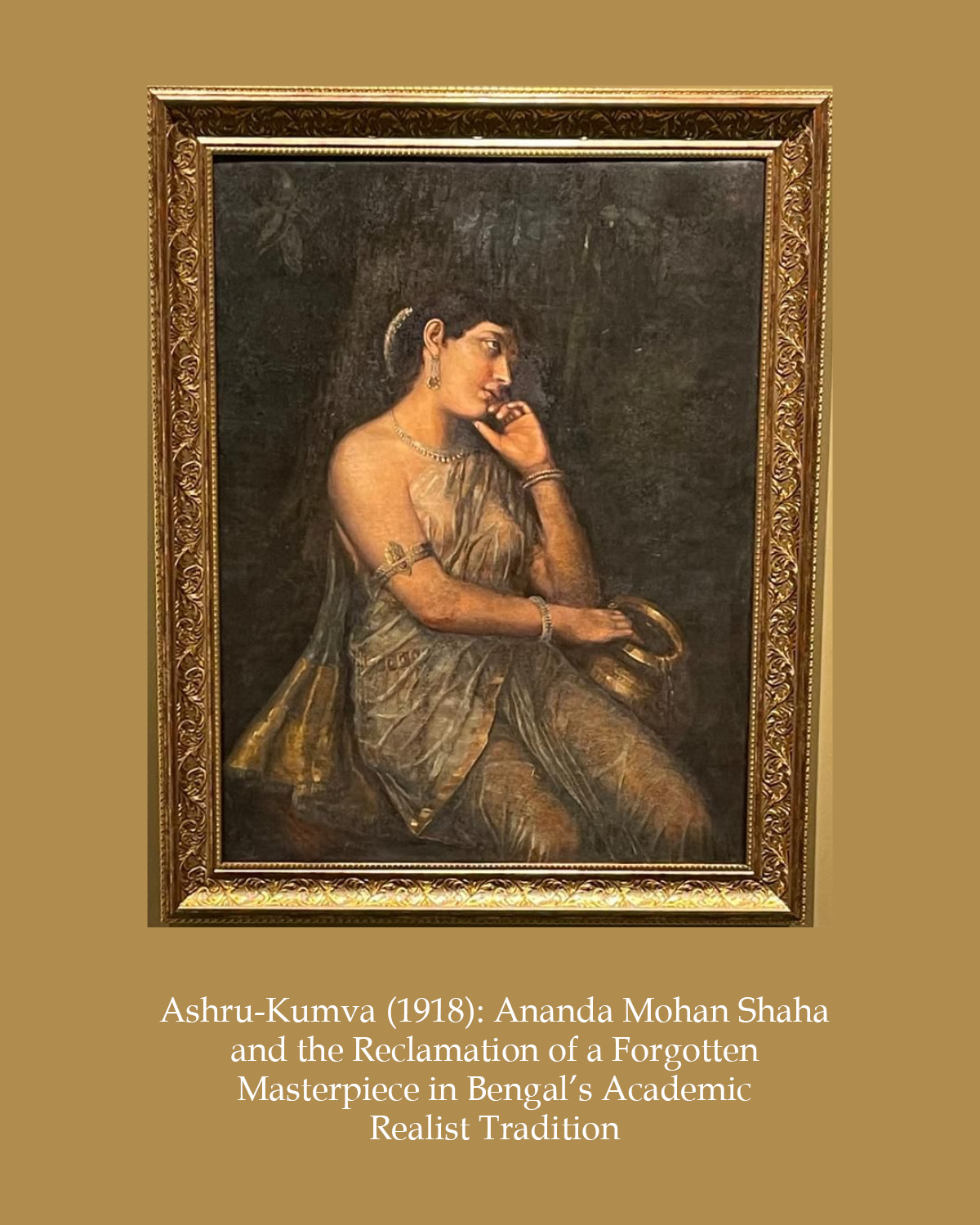

In the evolving landscape of Indian art historiography, there are rediscoveries that do more than just add to a catalogue—they alter our understanding of a forgotten lineage. The reattribution of the painting Ashru-Kumva (1918) to Ananda

Mohan Shaha (also spelled Saha)—a once-anonymous artist now reinserted into

the canon—represents such a moment. At once technically accomplished and

emotionally resonant, the painting survives today as a rare and remarkable

relic of Bengal’s academic realist movement, a strand of Indian modernity long

overshadowed by the Bengal School’s revivalist nationalism.

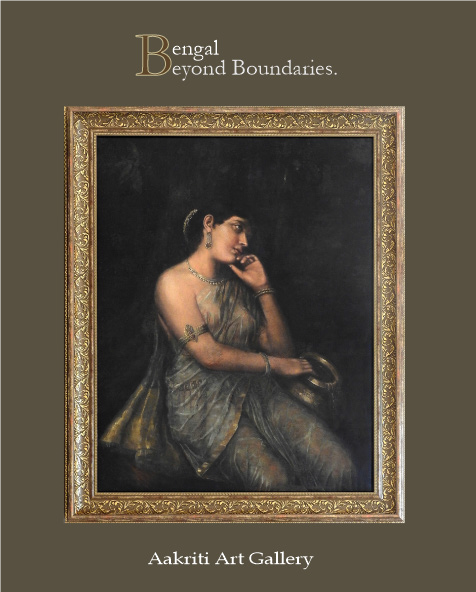

Cover of Bengal Beyond

Boundaries

Published by Aakriti Art Gallery 2023

Now housed in the collection of Aakriti Art Gallery, Kolkata, and prominently featured on the cover of its 2023 publication Bengal Beyond Boundaries, Ashru-Kumva invites critical reflection on the plurality of artistic voices in early 20th-century India. It reminds us that Indian modernism was never monolithic. Alongside the better-known proponents of revivalist or spiritualist idioms, there existed painters like Ananda Mohan Shaha—rooted in academic discipline, drawn to emotional realism, and deserving of serious scholarly attention.

The Artist: Ananda Mohan Shaha (fl. c. 1910–1920s) **

The signature in the bottom-left corner of the painting—Ananda Mohan Shaha, 1918—is the key that unlocks this long-lost attribution. While Shaha does not appear in conventional art historical dictionaries or biographical indices, the survival of this signed work, coupled with its early publication in the prestigious 1920 Puja Number of The Indian Academy of Art, confirms his position within the inner circle of Bengal’s academically trained realist painters.

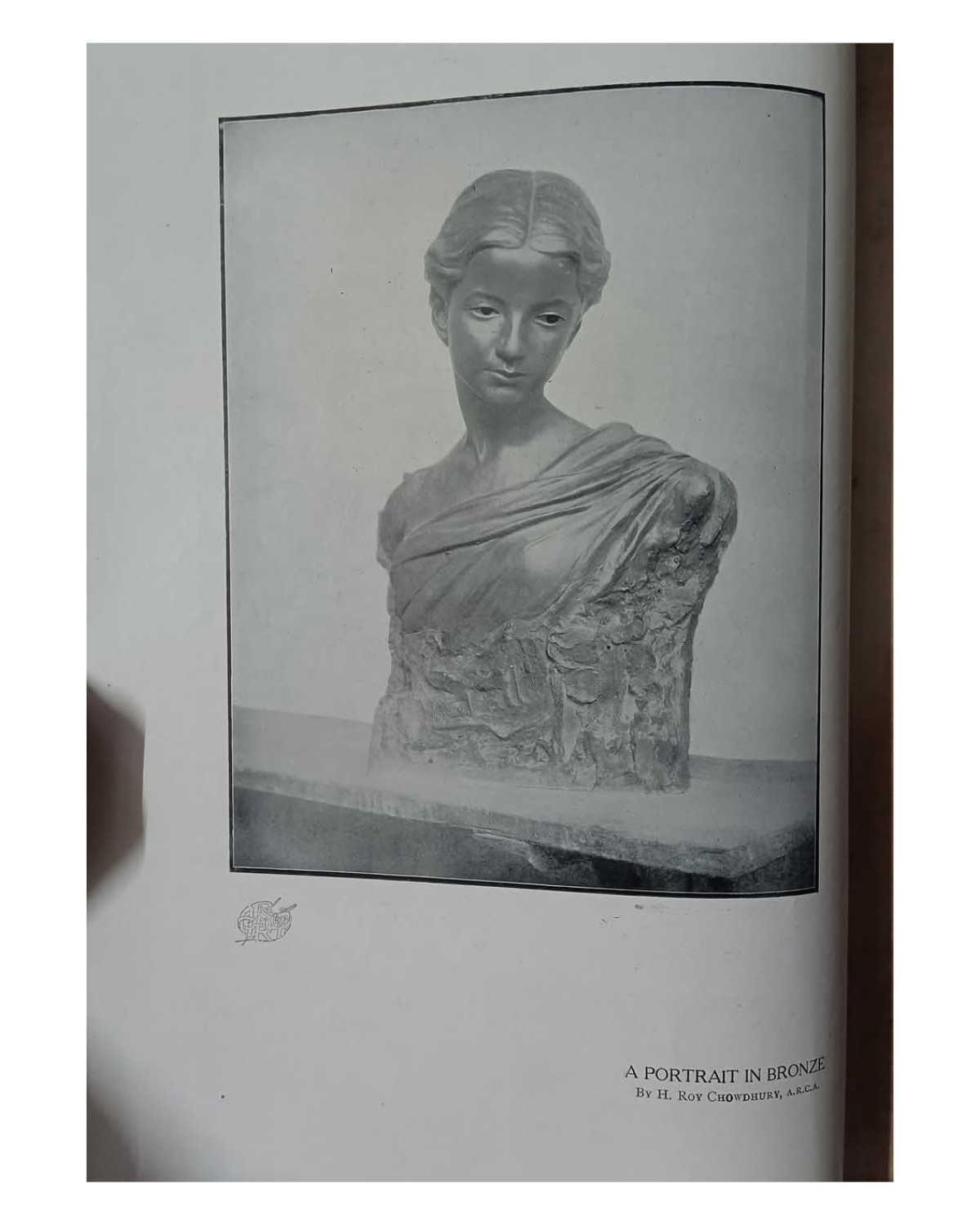

The precise details of Shaha’s artistic education remain unclear, but stylistic analysis suggests he was either formally trained at the Government School of Art, Calcutta, or part of an associated atelier that followed European academic techniques. His mastery of oil painting, compositional clarity, and anatomical precision place him in clear dialogue with contemporaries such as Hemendranath Mazumdar, Atul Bose, and B.C. Law—artists who embraced realism, portraiture, and figurative study at a time when the Bengal School, under Abanindranath Tagore, championed a contrasting vision rooted in Indo-Persian, Rajput, and Japanese aesthetics.

Where

the Bengal School turned toward mythology and spiritual allegory, artists like

Shaha chose a different vocabulary—drawing instead from lived experience, human

emotion, and the universality of visual observation. In doing so, they not only

created technically refined works but also laid the groundwork for a more

cosmopolitan Indian modernism, even if their names remained confined to the

margins of art history.

------------------------

** The

notation (fl. c. 1910–1920s) stands for:

• fl. = floruit (Latin),

meaning “he/she flourished”

• c. = circa, meaning

“around” or “approximately”

So, Ananda Mohan Shaha (fl. c. 1910–1920s) means that he was active or prominent as an artist around the 1910s to the 1920s, though exact birth and death dates are not known. This is a standard scholarly way of denoting the known active period of a historical figure whose full biographical details are uncertain.

------------------------

The Painting: Ashru-Kumva (1918)

Ashru-Kumva, which may be translated as “Urn of Tears” or “Vessel of Sorrow,” is a masterwork in oil on canvas. It features a seated woman, poised in contemplative silence, dressed in a sheer drape, adorned with jewellery, and holding a brass pot—the eponymous kumva—as if capturing or releasing invisible tears. Her expression is serene, her sorrow internalized, and her posture rendered with a realism that is both delicate and restrained.

Painted

in 1918, the work carries none of the theatricality or allegorical excesses

often associated with later salon-style academicism. Instead, it reflects a

refined emotional realism, rooted in Bengal’s visual culture yet executed with

a command of academic oil technique—evident in the transparency of the fabric,

the modelling of musculature, and the play of light against dark foliage in the

background.

The Context: A Counter-Movement to the Bengal School

To

appreciate the full importance of Ashru-Kumva, one must understand the art

historical moment in which it was created. By the second decade of the 20th

century, revivalism, led by the Tagores and institutionalized through the

Indian

Society of Oriental Art and journals like Rupam, had become the dominant

aesthetic ideology in Bengal. It promoted a “spiritual” art of line and wash,

rooted in Eastern traditions and consciously rejecting the naturalism taught by

colonial schools.

Importance and Rarity

Today,

Ashru-Kumva is the only known surviving signed work by Ananda Mohan Shaha,

making it a painting of exceptional rarity and historical value. Its

rediscovery and secure attribution not only illuminate the career of an

otherwise

unknown artist but also enhance our understanding of the diversity of early

Indian modernism.

Furthermore, the painting’s stylistic integrity, emotional depth,

and cultural specificity elevate it beyond mere rarity to significance. It

serves as a visual bridge between pre-Independence Indian realism and post-Ravi

Varma academic idioms, while maintaining a unique tenderness that distinguishes

it from the more opulent or sensual works of the era.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

With the reattribution of Ashru-Kumva to Ananda Mohan Shaha, and

its preservation by Aakriti Art Gallery, a significant lacuna in Indian art

history begins to close. Shaha’s work reminds us that Indian modernism was

forged not just in the workshops of Santiniketan or the salons of Bombay, but

also in the quiet, sincere studios of painters who believed in the power of observation,

emotion, and realism.

The painting also resonates today in a world increasingly attuned

to stories of marginalised creators, lost legacies, and plural histories.

Shaha’s quiet woman with her urn of tears, painted in 1918 in the midst of

global war and colonial upheaval, still speaks—perhaps now more than ever—with

clarity and grace.

Ashru-Kumva is not simply a rediscovered painting—it is a rediscovered voice. The hand of Ananda Mohan Shaha, once nearly erased from the annals of Indian art, emerges through this work as a reminder that behind every movement lies a multitude of individual choices, craft traditions, and aesthetic values. His legacy, enshrined in this luminous painting, deserves a place not in the footnotes of Bengal’s art history—but at its very heart.