- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Memories of a Master

- The Gallery as Print Studio

- Printer as Pedagogue

- Perspectives of an Outsider

- Ghosts in the Machines

- Digitalization and Contesting Digitalization

- The Body in Woodcut

- Evoking Symbol and Redefining Space

- The Almanac of Debian Delight

- Permanent State of Suspension

- Perspectives on Survival

- A Look at Printmakers from Australia, Canada and Bangladesh

- Atin Basak: His Artistic Pursuit

- Chor Bazaar, Mumbai

- Didn't We Often Wish We Lived in a Time of Ancient Glory

- The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Art of Gandhara, the Asia Society Museum, New York

- Slivery Facets of Golden Diamonds from Golconda

- Ulysse Nardin: Keepers of History

- Venice Biennale

- What Happened with “Deconstruction India”

- Publication of Graphic Folio by the Members of Society of Contemporary Artists, 2010

- A Blitzkrieg of Creative Impulses

- Let's Paint the Sky Red- A Solo Show of Late Artist Manjit Bawa

- Raghu Rai: Invocation to India - A Variegated Matrix of the Human Predicament

- Rise of Prints

- The Story So Far

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Few Printmakers from North East: A Brief Glance at the Contemporary Practices

- Previews

- In the News

ART news & views

The Body in Woodcut

Volume: 4 Issue No: 20 Month: 9 Year: 2011

Chandramohan's woodcuts and his method of work

by Siddhartha V. Shah

As the great French philosopher, Michel de Montaigne, once noted, man is the sole animal whose nudity offends his own companions. For literally thousands of years, the proper representation of a nude form has served as a measure of an artist's talent and sensitivity, particularly in European art. And while many of India's artistic treasures represent some of the most sumptuous physical forms in the history of world art, the presence of the nude in Indian art has certainly diminished over more recent history to near oblivion. More often than not, a nude evokes discomfort in the general viewing public of India, perhaps a reflection of a collective mood of shame around nudity. Even the nude representations in stone or bronze of deities found in ancient Hindu temples are covered in layers of silk, ornaments, and heaps of flowers. The role of the nude in both early and contemporary Indian art is certainly perplexing and worthy of examination.

As the great French philosopher, Michel de Montaigne, once noted, man is the sole animal whose nudity offends his own companions. For literally thousands of years, the proper representation of a nude form has served as a measure of an artist's talent and sensitivity, particularly in European art. And while many of India's artistic treasures represent some of the most sumptuous physical forms in the history of world art, the presence of the nude in Indian art has certainly diminished over more recent history to near oblivion. More often than not, a nude evokes discomfort in the general viewing public of India, perhaps a reflection of a collective mood of shame around nudity. Even the nude representations in stone or bronze of deities found in ancient Hindu temples are covered in layers of silk, ornaments, and heaps of flowers. The role of the nude in both early and contemporary Indian art is certainly perplexing and worthy of examination.

Even more provocative or challenging than representing a nude figure in a work of art is when an artist, such as Srilamantula Chandramohan, displays his own body before the viewer in a larger-than-life format and presents it as a canvas upon which he reveals his inner states, experiences, fantasies and struggles. His name first reached the public in 2007 following a controversy at Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda when conservative Hindus and Catholics, along with political officials and policemen, stormed a private examination hall where Chandramohan's works were displayed. The artist, just a student at the university in his mid-20s, was subsequently arrested for “offending religious sentiments”, drawing the attention of countless activists and established artists who fought against censorship and for the freedom of expression in India. Following the fiasco at M.S. University, Chandramohan spent a considerable amount of time away from the public gaze while the fueled discussion of censorship in Indian art continued to gain international attention.  His story remains an important part in the evolution of contemporary Indian art in the 21st Century and his technique, subject matter and unique style all merit attention.

His story remains an important part in the evolution of contemporary Indian art in the 21st Century and his technique, subject matter and unique style all merit attention.

Chandramohan resurfaced in 2010 with his first solo exhibition which was held at Serindia Gallery in Bangkok, Thailand, and signaled his return to the world of contemporary art. With some conservatives in India still upset about his works, many were not sure how the show would be received by an international audience. When nearly 2/3 of the show sold within the first week of the opening and positive reviews were coming in from critics around the world, it became clear that Chandramohan is an artist with a unique vision and perhaps even more unique technique that, when brought together, reveal a body of work that is truly emblematic of modern India. Whereas India may not have been prepared to receive his provocative message, various connoisseurs have identified an exceptional artist worthy of being collected. The exhibition in Bangkok propelled the artist onto an international platform and a forthcoming catalog of his woodcuts from 2006-2008 is due out in the coming year with the same title as the show The Body Never Lies.

Chandramohan, a native of Andhra Pradesh, first trained as a painter in Hyderabad before pursuing a masters degree in printmaking in Baroda. Hailing from a traditional carpentry family in South India, he found the medium of woodcutting immediately comfortable and appropriate as it was a connection to his ancestry and family lineage. Whereas his family members would carve intricate details into wooden furniture, his interest was more in the natural material itself. Though he had very limited experience with printmaking in Hyderabad, he knew that this was the direction he wanted his work to move in, and that in Baroda he would have the opportunity to train under the guidance of some of India's greatest artists. Upon arriving at M.S. University, he found himself thrust into a community of students, respected artists and professors who discussed theory, the “avant-garde”, and art in general in a way he had not previously been exposed to. While his emphasis had been on the depiction of labourers, street scenes, and local markets in his undergraduate studies, it was exposure to the work of Bhupen Khakhar that revealed to Chandramohan the potential for art to speak of one's personal, inner realms. Khakhar, one of Baroda's most acclaimed modern artists, was renowned for his fantastic paintings that told stories in a magical visual language. In his works, he often explored sexuality and, more personally, his own homosexuality in a style imbued with innocence and playfulness. Chandramohan found an expression of freedom in art, creativity, and the exploration of daring subject matter in Khakhar's paintings. The truth he found in these works, as well as the great artist's commitment to authenticity in expression, became an inspiration for Chandramohan's subsequent woodcut prints.

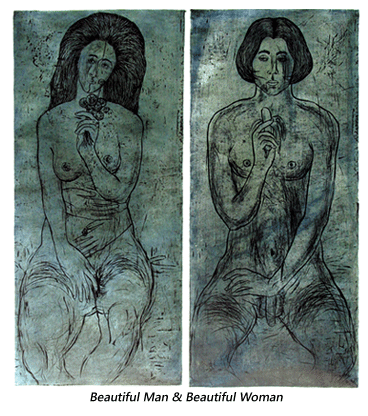

While he excelled at working with paint on canvas, the medium of printmaking and, more specifically, woodcutting, afforded him a wider visual vocabulary than working on a flat canvas or drawing on paper. His background in painting led him to bring his own painterly quality to printmaking which was criticized at first as most students in the department worked in a more traditional, monochromatic style. His first woodcuts as a student at M.S. University, a pair called simply Beautiful Man/Beautiful Woman, remain his only compositions devoid of his characteristic colour. They reveal his burgeoning interests in nudity and sexuality that would eventually suffuse his entire body of work. Chandramohan explores the ideal male and female forms in this diptych, featuring two nude figures seated and gazing out directly at the viewer. Beautiful Woman is evocative of Pablo Picasso's representations of Francoise Gilot whose portraits emphasized her full hair, affection for flowers and a divided face. Her features are attractivelong eyelashes around almond-shaped eyes, full breasts with perfectly round nipples. She lifts a small bouquet of flowers to her face with one hand while the other reaches down as if to cover her nudity while directly gesturing toward her pubic region. Beautiful Man shows a handsome young man with distinguished features, a strong and full chest, dark hair, and with a firm banana that he lifts toward his mouth. Like his female counterpart, he moves his hand toward his waist as if to cover his nudity, but the position of his hand serves more to draw attention  to his penis than to hide it. His eyes reveal that he is utterly unaffected by the viewer's presence or gaze.

to his penis than to hide it. His eyes reveal that he is utterly unaffected by the viewer's presence or gaze.

Beautiful Man/Beautiful Woman mark the beginning of his career as a printmaker and, from that point on, the artist quickly discovered a style of his own. The bold, fearless use of colour is one of the signifying traits of Chandramohan's work and he found that he could best express his inner passions with vibrant colours into his printmaking practice. Having a strong foundation in painting, Chandramohan has an intimate understanding of and relationship to colour, and he incorporates bold, saturated colours into his prints in a way that is virtually overwhelming to the eye. In other words, the intensity of the colour highlights and compliments the intensity of the subject. There is a graphic quality to his work that echoes the extremely saturated colours used by American graffiti/POP icon of the 1980's, Keith Haring, who combined vibrant inks with his highly erotic subjects in screenprints. Where Chandramohan goes even further than Haring is in his distinctive layering of colours. By using one block for each composition (rather than one block for each colour application), the completed image reveals the texture of the wood as well as a particular blend of intense colours that could hardly be replicated in a painting. Indeed, it is only through the medium of woodcut and by using the medium in this particular way that Chandramohan is able to achieve this effect.

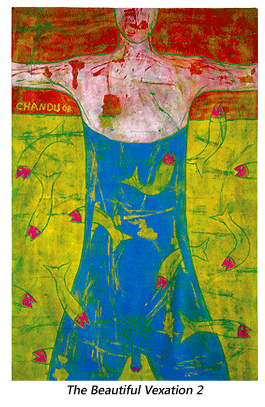

Where Chandramohan challenges the viewer the most is in his raw and honest representations of himself in enormous compositions. In these works, he shows himself as an elongated standing figure either mostly or completely nude, as if crucified and totally exposed for the viewer. At times, the depicted figure seems to revel in his fantasies and find pleasure in the realm in which he finds himself. In others, the body is an allegorical symbol for intense emotional states that communicate shame and remorse. His series of prints entitled Beautiful Vexation explores fantasies of a magical and sexual dimension, presented in larger-than-life, iconic imagery. Beautiful Vexation II from 2008 is a large-format, six-colour woodcut that is one of the most ambitious works of Chandramohan's career to date. A faceless man, understood to be the artist himself, stands naked before the viewer with his arms stretched out to either side and his legs slightly opened. He is partially submerged in a pool of water surrounded by fish with pink heads that echo the shape and colour of the figure's genitalia. There is, indeed, a magical, fantastic quality to this composition; the scene reverberates with the energy of a deeply personal dreamscape. The supple fish swim around the figure and some even penetrate his body, winding their way in and out of his torso. The image vibrates with sensuality as we, the viewers, are confronted with the artist's fantasy and made voyeurs to his sexual musings.

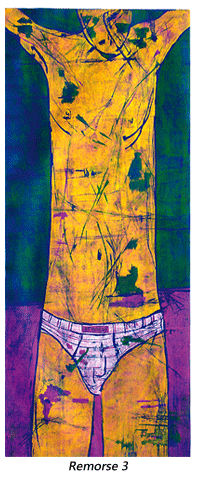

In his prints that reflect on remorse, shame, and repression, Chandramohan's large-scale “self-portraits” communicate an entirely different facet of the artist's inner experience. In 2006, his woodcut print called Remorse earned him the prestigious Lalit Kala Akademi National award. He revisited this theme following his arrest in 2007 in a number of works that communicate pain and humiliation in a way that could perhaps only be expressed so effectively through the medium of woodcut. Remorse III, yet another large format print, depicts the elongated torso of a male figure that, like the subject of Beautiful Vexation II, has his arms reaching out to the side. This time, however, the arms also reach up alluding to crucifixiona universal symbol of sacrifice and violent humiliation.  The surface of the plywood block melds powerfully into the image and, through the application of various colours, creates a sense of depth, texture, and vibrant light. Most remarkable, though, is Chandramohan's aggressive lines and harsh patches on the body of the figure depicted. By gouging, scratching, and splitting the wood, he presents a naked body that is truly tortured and reveals the wounds to the viewer. Even in terms of the artistic processthe artist takes a sharp tool and violently carves into a large-scale representation of himselfthis work expresses an intensely intimate aspect of his psyche and presents it in a truly innovative and modern visual language.

The surface of the plywood block melds powerfully into the image and, through the application of various colours, creates a sense of depth, texture, and vibrant light. Most remarkable, though, is Chandramohan's aggressive lines and harsh patches on the body of the figure depicted. By gouging, scratching, and splitting the wood, he presents a naked body that is truly tortured and reveals the wounds to the viewer. Even in terms of the artistic processthe artist takes a sharp tool and violently carves into a large-scale representation of himselfthis work expresses an intensely intimate aspect of his psyche and presents it in a truly innovative and modern visual language.

To say Chandramohan's works are "provocative" minimizes the purity of the artistic genius that is displayed before us. His prints force us to look deep within our own psyches, invoking energies that might feel uncomfortable to some, electrifying to others. Our own experiences, fantasies, and struggles are presented before us in enormous representations filled with bold colour, clear lines and imbued with an undeniable erotic quality. The prints depict moments of frozen action that guide the viewer, subtly and organically, into moments of erotic contemplation. Chandramohan is at the forefront of a new vanguard of modern Indian artists, pushing his contemporaries and the viewing public into an era of fresh, bold, and challenging artistic expression. In many ways, he is redefining the potential visual effect of printmaking, using the medium in a manner that honors tradition while signaling contemporary transformation.

Chandramohan's process of creating woodcut prints

1. A piece of plywood is chosen that will be the size of the image printed onto paper. The edition size is determined before any carving takes place on the wood surface.

2. The plywood is gently pressed onto the sheets of paper (corresponding to edition size) to get an impression of the four edges of the wooden board. This becomes the working area for the artist's composition.

3. A base colour of letterpress ink is hand-rolled onto the working area of each sheet of paper and allowed to dry.

4. The composition is drawn in chalk onto the wooden board before it is carved.

5. The outline of the figure(s) is the first part to be carved. A colour is selected (other than the base colour) and is rolled across the wood block. The paper is placed against the wet board and rubbed with either a cloth or spoon to transfer the ink onto the paper. This coat of ink transfers onto the paper except in the areas that have been carved out.

6. He then carves the wood again, adds another coat of letterpress ink in a different colour to the wooden board and presses the dried paper against the block. When the block is removed, the surface of the working area will be coated in this third colour, except the areas carved out prior to this coat.

7. Each edition is done separately at every level of carving/printing, depending on how many colours are used for each print. Given the various involved stages, additional prints cannot be made once the wooden board has been completely carved out.