- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- In Conversation with Kanishka Raja

- Definitional Lack in an Inclusive World: Cutting Edge as Responsible Art

- Democratization Through Cutting Edge Art

- Mumbai for Cutting Edge

- Moments in Time (And a Little While After)

- In Transition

- Tip of Our Times

- Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology – A Cradle for Creative Excellence

- Cutting the Edges of Architecture

- Overview Cutting Edge

- The Matter Within: New Contemporary Art of India Featuring Photography, Sculpture and Video

- Generation in Transition: New Art from India

- Indian Master Painters at India Art Festival

- Life, Luxury & the Avant-Garde

- Mother India: The Goddess in Indian Painting

- The Last Harvest: Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore

- Asia Society Museum Presents Exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings and Drawings

- Stieglitz and his Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffee

- Beauty of Unguarded Moments

- Across Times, Across Borders: A Report on the Chinese Art Exhibition

- A Summer in Paris

- Random Strokes

- The Emperor’s New Clothes and What It Really Means

- Understanding Versus Adulation

- What Happened and What’s Forthcoming

- Occupy Wall Street, The New Economic Depression And Populist Art

- Unconventional with Witty Undertones

- Narratives of Common Life and Allegorical Tales In Traditional and Modern Forms the Best of Kalighat 'Pats'

- Colours of the Desert

- Unbound

- I Am Here, An Exhibition of Video Self Portraits at Jaaga

- Staging Selves: Power, Performativity & Portraiture

- Venice Biennale Outreach Programme A Circle of Making I and II

- Cartography of Narratives, Contemplations on Time

- Joseph Kosuth: The Mind's Image of Itself #3' A Play of Architecture and the Mind

- Maharaja: Reminiscing the Glorious Past

- Art from Thirteen Asian Nations

- Tibetan Arms and Armor at Metrpolitan Museum of Art

- The Art of Poster Advertisement

- Unusual Angles and Facets of Museum Buildings

- Elegant Fantasies

- Art Collection and Initiatives

- Art Events Kolkata

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview

- In the News

ART news & views

Understanding Versus Adulation

Volume: 4 Issue No: 22 Month: 11 Year: 2011

Market Monitor

by Art Bug

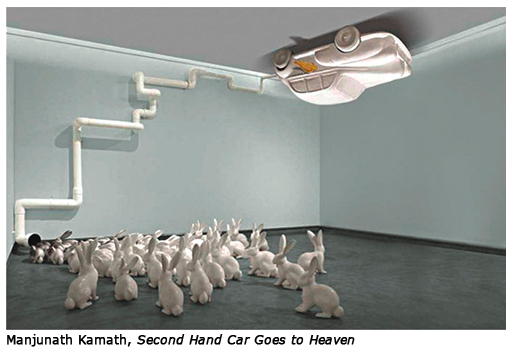

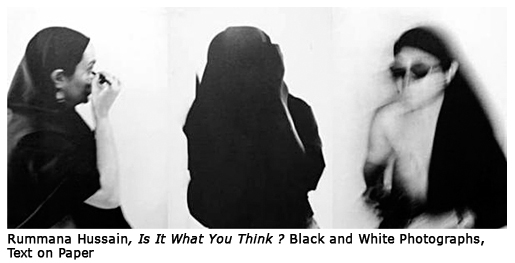

A lot has been written and said on 'cutting edge art' in India since the beginning of this millennium, but sadly, to tell the truth, even after 14 years (taking for instance that the 'cutting edge matrix' gained contextuality in India from 2000 onwards, with Peter Nagy reformatting his New York gallery, Nature Morte, as a curatorial experiment in Delhi, in 1997) the market contextuality of this genre of art still remains missing in this country. While the likes of Damien Hirst take the auction bulls by their horns and redefine a global market trend, Indian artists, like Navjot and Manjunath Kamat, or Rummana Hussain, Anita Dube, Sonia Khurana remain more popular in drawing room conversations than in curatorial and galleric (if one may use that expression, which by itself is 'cutting-edge') interest, not to speak of indigenous auctions where cutting-edge Indian art still is a rarity.

.jpg)

It is therefore natural that data regarding the market size of Indian cutting edge art is hard to come by. One of the reasons, according to one school of thought is the lack of government as well as private institutional support. Cutting edge art globally has historically been commissioned by large corporate or government institutions, thereby enabling the artists to enter into a dialogue of neo-political matrices. However, in a country like India, torn between the extremes of traditionalism, caste-based politics, socio-economic complexities and poverty-line debates, that would, despite the fact that it is more essential here than elsewhere, would be an adventitious prerogative especially for government sponsored institutions. It is thus left to a few private individuals to nourish and nurture this art form in the Indian context.

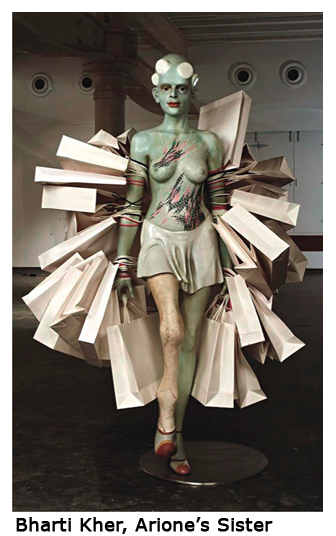

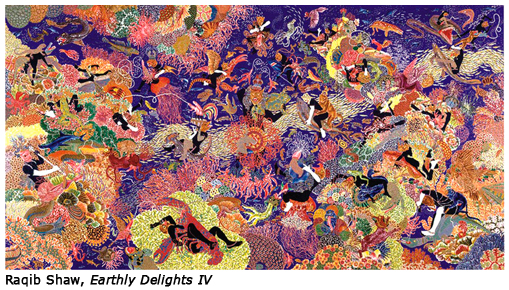

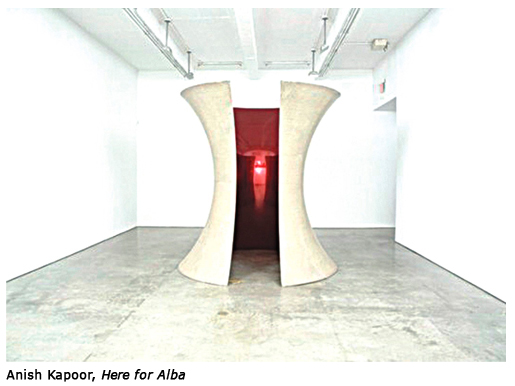

However, internationally, there is enough data available for Indian contemporary cutting-edge artists who have made it big. According to ArtTactic, “boosted by specialised sales, Contemporary Indian art has shown an impressive progression: over the ten years to January 2008, our price index for this category posted growth of 830%! Among the stars of 2010 auction sales there were four Indian artists: Bharti Kher, Anish Kapoor, Raqib Shaw and Subodh Gupta.

The top 5 auction results in 2010 for Indian contemporary artists go like this:

Bharti Kher sold for $1 280 610 (The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own) at Sotheby's London, followed closely by Anish Kapoor at $1 200 000 (Here for Alba) at Sotheby's, New York. Kapoor's Untitled clocked $900 000, his Green Rainbow Mirror clocked $828 905 while Raquib Shaw's Garden of Earthly Delights XIV went for $751 728. (Source: ArtTactic.com)

Bharti Kher sold for $1 280 610 (The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own) at Sotheby's London, followed closely by Anish Kapoor at $1 200 000 (Here for Alba) at Sotheby's, New York. Kapoor's Untitled clocked $900 000, his Green Rainbow Mirror clocked $828 905 while Raquib Shaw's Garden of Earthly Delights XIV went for $751 728. (Source: ArtTactic.com)

At this point, let us see what kinds of works are being worked upon in this new-media form of art, which, in other words is also described as 'cutting edge'. Writer, art-critic and Mumbai-based curator Nancy Adajania, in a 2009 article for the Goethe-Institut, had done a fine summary of the practicing artists of this form in India. She writes,

At this point, let us see what kinds of works are being worked upon in this new-media form of art, which, in other words is also described as 'cutting edge'. Writer, art-critic and Mumbai-based curator Nancy Adajania, in a 2009 article for the Goethe-Institut, had done a fine summary of the practicing artists of this form in India. She writes,

“…it is important to interweave the narrative with the crucial interventions in networking and infrastructure-building for alternative art made by two fortuitously complimentary catalyst figures, the American artist-turned-curator Peter Nagy and the arts manager and curator Pooja Sood. While Nagy promoted innovative gallery practice, Sood acted as a catalyst for an international artists' workshop which liberated artists from the confines of the gallery. Nagy … cut right through the then prevalent debate in Indian art circles, between those who believed that painting was exhausted as a medium and installation art was the next big thing. Neither a purveyor of dogma nor a chaser of fashion, Nagy showed photographs and installations alongside paintings and drawings. More significantly, he brought photography, installation and video art into the conversation of the Indian art world, imparting to them both intellectual legitimacy and economic currency. In the same year that Nature Morte, Delhi opened its debut show, the Khoj International Artists' Workshop held its first exchange programme in Modinagar, Delhi. Khoj is a feat of cultural management, an artists initiative catalysed, facilitated and sustained by Pooja Sood (its first working group comprised Ajay Desai, Anita Dube, Bharti Kher, Subodh Gupta, Manisha Parekh and Prithipal Singh Ladi).

“Khoj (a portable model of transcultural artistic conviviality inherited from the Triangle Arts Workshop, New York, 1982) was able to provide an alternative space to artists to experiment with media other than painting. Most importantly, it liberated artists from the commodity focus of the gallery system; its lively laboratory atmosphere brought Indian cultural producers into close communion with their colleagues from other countries, breaking down the nation-centric self-discourse then in force. Khoj emphasised the importance of process over product: sculptors could work with installations, painters with performance art and the rudiments of video art and public art were put into place here. Again, it was the indefatigable Pooja Sood who became the curator of The Apeejay Media Gallery, the first new media arts space in the country, in early 2000.

“…Most of the new-context media artists work between media, between shadow installations and video (Nalini Malani), video and sculpture installation (Vivan Sundaram and Sheba Chhachhi), video animation (Navjot and Manjunath Kamath), the Net and painting (Baiju Parthan), painting and video (Ranbir Kaleka), in a variety of performance-based video art and video installations (Rummana Hussain, Anita Dube, Sonia Khurana, Subodh Gupta, Shilpa Gupta, Kiran Subbaiah, Atul Bhalla, Nikhil Chopra and Tejal Shah). Some collectives address the experimental re-socialisation of communications technology: Raqs Media Collective, Delhi (Monica Narula, Jeebesh Bagchi and Shuddhabrata Sengupta), Camp, Bombay (Shaina Anand, Ashok Sukumaran and Sanjay Bangar) and the Desire Machine Collective, Guwahati (Sonal Jain and Mriganka Madhukaillya). A node that has come to play an important role in this domain is the Centre for Experimental Media Arts (CEMA) at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru, with its emphasis on transdisciplinary exploration and pluralised creativity, which blurs the conventional 'hard/ soft' boundaries between the sciences and the arts.”

This portion from Adajania's article gives a concise view of the cutting-edge scene in India, both in terms of the practicising artists as well as in terms of the curatorial practices now prevalent in the country. It is true, that over the decade consciousness about 'cutting-edge' has grown exponentially in India and it is now almost a matter of practice for galleries to hold regular 'cutting-edge' shows. However, patrons are still hard to come by. Why is that so?

This portion from Adajania's article gives a concise view of the cutting-edge scene in India, both in terms of the practicising artists as well as in terms of the curatorial practices now prevalent in the country. It is true, that over the decade consciousness about 'cutting-edge' has grown exponentially in India and it is now almost a matter of practice for galleries to hold regular 'cutting-edge' shows. However, patrons are still hard to come by. Why is that so?

First and foremost, serious cutting edge art may not necessarily be cash-intensive, though in most cases they are, but they are definitely labour-intensive and at times tech-intensive too. Adajania in the same article gives an example: “…one of the most remarkable public art interventions made in the realm of televisual reality and community networking is that of Shaina Anand's Khirkeeyaan made during an artists' residency at Khoj. Anand produced collaborative conversations and performances among friends and strangers residing in different neighbourhoods in Khirkee village, through an open-circuit TV system deploying TV sets, cheap CCTV equipment and several metres of cable snaking through the streets.

“Paradoxically, these ephemeral conversations, beamed as four views/performances on the TV screen, were marked by the stubborn and indelible fault lines of caste, class, religion and gender. This is undoubtedly the liveliest interface between technology, site and community in Indian art: Anand created a situation where the 'film' was made instantly, without the presence of a cameraman and editor; here, the participant was also witness-viewer and user. Not only did she stand the genre of classical documentary (the top-down approach to communication) on its head, but she also pierced a hole through the specious claims of the televisual media, which are believed to dole out democracy cheaply through SMS polls and hard-talking TV shows.”

A project of this nature may not necessarily be possible everywhere. Moreover, the tradition-bound concept of 'preservation' may not apply to such 'cutting-edge' art forms. Most importantly, Indian connoisseurs are still not ready with the kind of infrastructure and logistical support that may be needed to preserve and forward cutting-edge art matrices.

To end, we may quote Adajania again“The Indian art world sorely lacks a cumulative model of knowledge and expertise. Many of us move from one novelty to another, in many cases even redundantly reinventing the wheel. In a strange way, the new popularity of these art forms will bury them in plain sight…While galleries today no longer reject 'new media art', and even include such practices as an extension of patronage, not enough discourse is generated around such questions as the demographics of reception, the politics and ethics of producing such art and the curation of dematerialised art. To paraphrase the radical historian D. D. Kosambi - who informed Indian Communists that Marxism was not a substitute for thought - we would do well to recall that technology cannot be a substitute for criticality.

“In the context of new media art, we have made the transition from indifference to uncritical acceptance, even adulation. Now is the time for quiet reflection and healthy skepticism.”