- Prelude

- Editorial

- Subodh's 'return home'

- A Conversation with TV Santosh

- It's a War Out There

- Raqib Shaw

- Illusions in Red from a very British Indian Sculptor

- Stand Alone: Shibu Natesan

- Reading Atul Dodiya

- Bharti Kher: An Obsession for Bindis

- Bose Krishnamachari

- The Image - Spectacle and the Self

- From Self-depiction to Self-reference: Contemporary Indian Art

- GenNext: The Epitome of New Generation Art

- Kolkata's Contemporary Art A Look in the Mirror

- Innovation Coalesced with Continuing Chinese Qualities

- Kala Bhavana-Charukala Anushad Exchange Program

- Montblanc Fountain Pens

- Dutch Designs: The Queen Anne Style

- Bangalore Dance Beat

- Decade of change

- Distance Between Art & It's Connoisseur

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- 3rd India Art Summit

- New Paradigms of the Global Language of Art

- Black Brown & The Blue: Shuvaprasanna

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Printmaker's Season

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- The Pause of Profound Stillness

- Previews

- In the News

- The Rebel Queen: An icon of her own times yet looked down upon

ART news & views

Bose Krishnamachari

Volume: 3 Issue No: 14 Month: 3 Year: 2011

by Uma Prakash

Bose Krishnamachari is an artist and curator whose work comprises of vivid abstract paintings, figurative drawings, and sculpture, photography and multimedia installations. Krishnamachari's mastery of colour, his techniques and his usage of various mediums are a source of inspiration and speculation. In his paintings the lyrical mix of colour and strong geometrical patterning on paper and canvas, is a unique visual experience, exuding a sense of magical realism. In his installations the artist questions the significance of the existing powers that influence the art world and addresses the unjust discrimination in different strata of society.

Bose Krishnamachari is an artist and curator whose work comprises of vivid abstract paintings, figurative drawings, and sculpture, photography and multimedia installations. Krishnamachari's mastery of colour, his techniques and his usage of various mediums are a source of inspiration and speculation. In his paintings the lyrical mix of colour and strong geometrical patterning on paper and canvas, is a unique visual experience, exuding a sense of magical realism. In his installations the artist questions the significance of the existing powers that influence the art world and addresses the unjust discrimination in different strata of society.

Born in Kerala, Krishnamachari studied at Sir J J School of Art, Mumbai. The artist's journey from his village in Kerala to Mumbai has been an exciting, cultural and learning experience. The artist's involvement with the art began with his interest in paintings and theatre. He acted in translated versions of Samuel Becket's play in Malayalam. He enjoyed film, music, poetry and reading. He first joined Kerala Kalapeetom a small art institute in Kerala. However after he moved to Mumbai his perception of art completely changed as he found himself completely drawn to abstract art. The visual language of this non-representational art form greatly appealed to him.

In Mumbai he interacted with artists like Akbar Padamsee, Laxman Shreshtha, Barve, Gieve Patel, Deepak, Altaf, Navjot, Sabavala, Tyeb Mehta, Riyas Komu, Prabhakar Kolte, Mehli Gobhai, Atul Dodhiya and Sudarshan Shetty. He was excited by their abstract works and inspired by their confidence in experimenting with different mediums.

Krishnamachari's work includes an unusual treatment of photographic elements as well as vibrant, colourful abstraction.  His canvases embrace a spectacular combination of colour, texture and distinct designs, with a strong cerebral base. The conceptual angle of modern British art impressed him most during his recent tenure at Goldsmith College, London. Krishnamachari challenges the single interpretation of an image as he seeks numerous connotations. Even in his abstract patterns he persuades the viewer to look for several explanations.

His canvases embrace a spectacular combination of colour, texture and distinct designs, with a strong cerebral base. The conceptual angle of modern British art impressed him most during his recent tenure at Goldsmith College, London. Krishnamachari challenges the single interpretation of an image as he seeks numerous connotations. Even in his abstract patterns he persuades the viewer to look for several explanations.

In his first solo show in 1990, Krishnamachari displayed a minimalist style, creating an abstract black on black with white perforated paper, reminiscent of Braille. The subtle work reflected a satirical observation of the distant and unapproachable gallery environment.

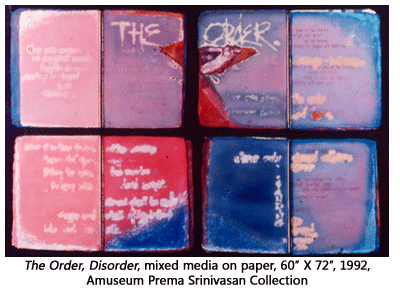

Another strong response against authority was clear in AmUseuM in 1992.It featured a series of open spiral bound books inscribed with poetry. It is interesting how some of the pages were glued together. He painted over them, placed them in glass cases giving them a museum like appearance. Here he had created a fusion of various disciplines, including literature and design. With the clever blend of “muse”, “use” “amuse” and the sacred “AUM” in his title the cynical artist articulated No museum. The artist goes further by creating his own artistic sanctuary with found objects.

He carried this idea further in 1995 when he converted objects like Tiffin carriers (an integral part of the life of a Mumbaikar), strap handles, diyas, and a workman's gloves into museum pieces by adding gold and placing them in small cavities covered with glass like a display case.

Bose Krishnamachari believes the actual artistic practice is more significant than theory concepts and ideas. He believes in Karl Marx's philosophy “Man is a maker”. It is this affinity with the artist's community that lead to a ground breaking work called De Cuarating- Indian Contemporary Artists in 2003 consisting of 94 paintings and sketches of living Indian artists. This tribute to the art world, comprising of established and promising artists, was compiled after a research of three years. Being himself an artist Krishnamachari empathized with their trials and tribulations.

Furthermore he made ball point portraits of the people who work for his household in Mumbai together with the 108 photographs of the individuals he has encountered in his life in portraying the average 'Mumbaikar'. By illustrating images of those employed by him he displays the unfair distribution of wealth among different layers of society which is taken so much for granted in big metropolitan cities like Mumbai. What emerges is Krishnamachari's affinity for the underprivileged.

Ghost / Transmemoir is a dizzy installation of 108 used Tiffin's (or 'dabbas'), serving to frame video loops showing interviews with a multitude of Mumbai residents from all levels of society. It reflects a significant aspect of Mumbai, a city where the 'dabba' plays an important role in the everyday ritual of delivering home cooked food. Filled each day by housewives, the boxes are collected and change many hands before they finally reach their owner on time for lunch. Collectively, the installation pulsates the cacophony and chaos of the city, whilst the small screen reflects the thoughts, frustrations, religions and emotions of the many people who add vitality to Mumbai.

Another installation displaying Krishnamachari's appetite for experimentation is evident in an installation 'LaVA' (Laboratory of Visual Arts) in 2006. He focused on the five decades in design, photography, art and architecture to provide a reference point for various visual art practices. LaVA, was a vehicle that seriously questions the incompetence of existing institutions and the importance of archives. He achieves this by displaying a contemporary temporary laboratory consisting of records on visual arts obtained from museums, institutions, galleries shops and street.

Abstract art, the most modern form of expression, helped Krishnamachari to pursue his ideas by liberating his mode of expression, sometimes aiming at infinity. This is obvious in his Stretched Bodies series. Here the artist's flair for colour is evident as he juxtaposes amazing planes of flat colour against skilful, virtually photographic, representations of his inimitable style instilled with an 'international' sensibility. Through the fusion of Western image-making techniques (such as the installation) with the indigenous the artist creates a visual language that boasts of aesthetic qualities and a magical efficacy.

In an earlier interview,  he has said: "I refine my colour to brightness. I have learnt this usage from the alternately subdued and lavish colour codes of Indian ceremonies and ritual performances; the costumes, the gestures of enactment..."

he has said: "I refine my colour to brightness. I have learnt this usage from the alternately subdued and lavish colour codes of Indian ceremonies and ritual performances; the costumes, the gestures of enactment..."

In Ghost, Music of the Cubes shows the versatility of the artist is when using watercolour and acrylic. His abstract canvases speak volume creating a perfect harmony in cobalt blue revealing his penchant for colours. Here the mysterious elements permeate a spiritual force, radiating the affirmation of the spirit in life.

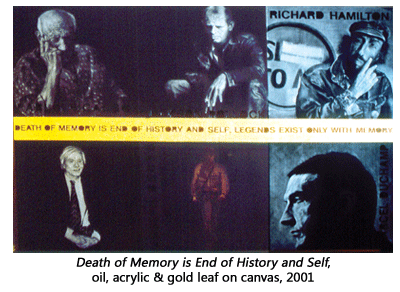

His recent body of work juxtaposes icons from different cultures. They include Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera, the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, and Rabindranath Tagore. Krishnamachari's aim is to create a holistic vision by amalgamating spirituality, epic style and (in Kahlo's case) a focus on the self as means to explore larger issues.

“I don't believe in art as local, art according to me, is global. It's everyone's right to see, everyone has the right to paint. I think art is everyone's language and there can be no discrimination towards art” (in conversation with Rucha Mehta).

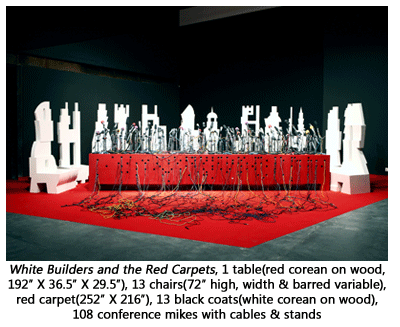

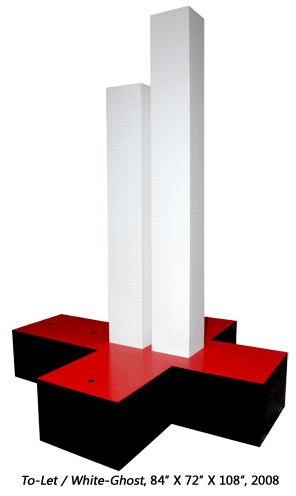

In another installation, Builders and the Red Carpets, 2008 Krishnamachari chooses to take a political viewpoint. He creates a press conference with 108 microphones on a long red table. The satire is revealed by the 13 imposing white chairs which represent the kind of influential persons who address the press to perpetuate wars for economic gain. The 13 chairs are symbolic of 'The Last Supper' and the destructive role religion plays in our wars. The installation is also a commentary on the necessity of information in the new media to combat the numerous 24 hour news channels.

“My work is political. There are many ways in which works can be shown. When I coming from a Kerala background and …consciously doing an abstract work, it's definitely a kind of a shift from what I used to debate. It's actually a political awareness which made me an abstract painter” (in an interview with Rucha Mehta).

Krishnamachari admits that being an artist and curator has its share of responsibility. “It is a kind of education. For me every project that I take up is an educational one. It is a job that institutions should be doing. Unfortunately we do not have much to write home about on that front. So we have to initiate such alternate methods. My own solo shows are conceived and executed as educational projects. All my art practices, personal and curatorial, are very much related to history, historical figures, practices and events. If you are not familiar with the history of art it is difficult to read them. Even the shows that I curate have historical references. It is your duty to show contemporary art practice and every time you do that it must be a memorable moment in history” (in an interview with Manoj Nair).

There is no end to Krishnamachari's achievements as both an artist and curator. His rich experience as an artist that has led him to enjoy other aspects of art like curating. After making a name for himself in Mumbai Krishnamachari is now active in the international art world.

Image Courtesy: The Artist