- Prelude

- Editorial

- Subodh's 'return home'

- A Conversation with TV Santosh

- It's a War Out There

- Raqib Shaw

- Illusions in Red from a very British Indian Sculptor

- Stand Alone: Shibu Natesan

- Reading Atul Dodiya

- Bharti Kher: An Obsession for Bindis

- Bose Krishnamachari

- The Image - Spectacle and the Self

- From Self-depiction to Self-reference: Contemporary Indian Art

- GenNext: The Epitome of New Generation Art

- Kolkata's Contemporary Art A Look in the Mirror

- Innovation Coalesced with Continuing Chinese Qualities

- Kala Bhavana-Charukala Anushad Exchange Program

- Montblanc Fountain Pens

- Dutch Designs: The Queen Anne Style

- Bangalore Dance Beat

- Decade of change

- Distance Between Art & It's Connoisseur

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- 3rd India Art Summit

- New Paradigms of the Global Language of Art

- Black Brown & The Blue: Shuvaprasanna

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Printmaker's Season

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- The Pause of Profound Stillness

- Previews

- In the News

- The Rebel Queen: An icon of her own times yet looked down upon

ART news & views

Raqib Shaw

Volume: 3 Issue No: 14 Month: 3 Year: 2011

Profile

by Sharmistha Ray

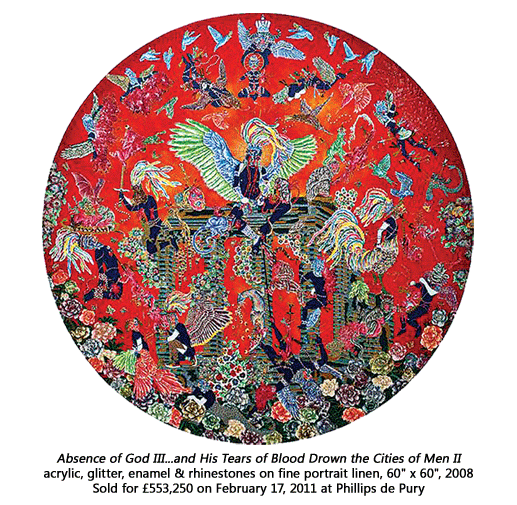

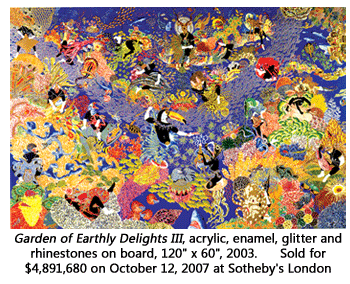

The highest paid artist to emerge from India is a reclusive London-based Kashmiri who pushes socially accepted norms with homoerotic paintings that seduce and subvert. Raqib Shaw first came into the public eye October 2007 when one of his paintings, a monumental triptych called Garden of Earthly Delights III sold for an incredible US$5.49 million at the Sotheby's Contemporary Art Sale, making it the most expensive art work by an Indian artist sold in an auction. It turned the then 33 year-old into an overnight sensation, catapulting him to the highest echelons of the international art world.

Shaw's work is inextricably tied to the Western art of the past, particularly to Medieval and Renaissance art so it comes as no surprise that his work should find a suitable showcase in one of the world's major antiquities Museum, which also boasts an enviable collection of the likes of Donatello, Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Vermeer. The exhibition is also seen as Shaw's response to the famous 'Holbein in England' exhibition held at Tate Britain in 2006-2007 that paid homage to Hans Holbein the Younger, the sixteenth-century printmaker and painter from the Northern Renaissance who has been a major influence on Shaw.

Before his record breaking sale in 2007, Shaw was relatively unknown outside of London. His meteoric climb has had few parallels even by London standards. Superstar artists like Damien Hirst and Matthew Barney, both of whom exploded onto the contemporary scene and became overnight sensations in the early nineties in London and New York respectively, commercial success followed artistic achievement. For Shaw however, they've gone hand in hand. Shaw's résumé includes solo exhibitions at Tate Britain in London and Museum of Contemporary Art in Miami (both in 2006) as well as inclusions in Passion for Paint exhibition at the National Gallery in London (2005), Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (2006) and Around the World in Eighty Days at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London (2006). Shaw's paintings have also found patronage  in such notable public and private collections as Tate Britain, MOMA, Rubell Family Collection in Miami and Dakis Joannous Collection in Athens, among others. All of which makes him the only second artist of Indian origin, apart from sculptor Anish Kapoor, who has gained fame and name with a predominantly western audience.

in such notable public and private collections as Tate Britain, MOMA, Rubell Family Collection in Miami and Dakis Joannous Collection in Athens, among others. All of which makes him the only second artist of Indian origin, apart from sculptor Anish Kapoor, who has gained fame and name with a predominantly western audience.

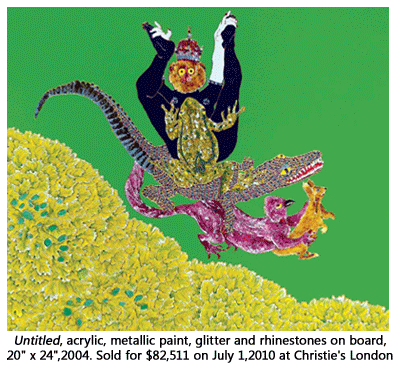

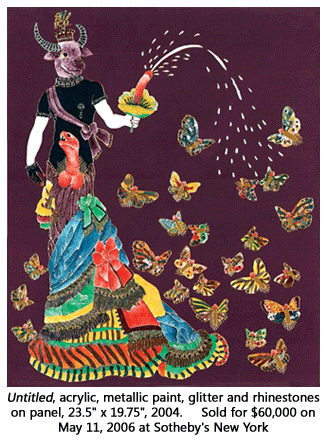

Raqib Shaw's visual language culls from a broad range of influences that reflect the artist's Eastern and Western sensibilities. The record-breaking painting Garden of Earthly Delights III for example, is largely indebted to traditional European painting that is combined together with techniques and practices whose roots can be traced to India and Japan. However, the dramatic narratives and fantastic scenarios that unfold on canvas are of Shaw's making entirely and come out from of an imagination obsessed with sexual pleasure and its implications. The large format, visually lush painting reveals a dramatic, violent and erogenous world in which strange, hybrid creatures engage in intense, erotic play in a submerged aqueous nether world. The leading protagonist at the center of the narrative is a Toucan King with a necklace of jewels and a crown perched on its head that emerges out of a florid sea urchin, brandishing its scepter like a grand conductor of an orchestra. Dramatic crescendo gives life to the underwater world and thousands of characters swirl to life.

A menacing piranha-like creature with anthropomorphic elements holds up a phallus ejaculating on the palm of his hand almost as an offering to the protagonist. Shoals of fish of every colour and size join the choreography along with sharks with gaping mouths, an array of squid, turtles, stingrays and jellyfish. Multicoloured coral, a plethora of sea flora and fauna create a fantastical setting which explodes the senses. Amid the chaos, a silent and still stag in full regalia with a golden halo stares at us. Hybrid creatures of a reptilian or monkey variety copulate and intertwine amorously with crustaceans of every kind, octopuses and other weird sea animals.

It's a delicious farce that takes its inspiration as well as its title from a visionary triptych by the early Netherlandish master Hieronymus Bosch. His 15th century triptych depicts several biblical and heretical scenes to illustrate the history of mankind according to medieval Christian doctrine. The left panel of this painting depicts God presenting to Adam the newly created Eve, while the central panel is a broad panorama of sexually engaged nude figures, fantastical animals, oversized fruit and hybrid stone formations. The right panel renders a hellscape that portrays the torments of damnation. Art historians and critics interpret the painting as a didactic warning of the perils of temptation.

In the light of this interpretation, Shaw's work reveals itself further: sexual freedom on Earth has its cost in the afterlife. Seen in the context of Shaw's homosexuality, these paintings take on new and layered meanings. In the Genesis, Adam and Eve submitted themselves to the forbidden fruit offered to them by Satan that appeared in the form of a serpent in the Garden of Eden. Shaw's paintings reveal similar temptations, and the curses of pleasure; the phallus offered up is akin to the forbidden fruit, and Shaw casts himself in the image of Adam, innocent but poisoned. Although Shaw's paintings are aesthetic delights, the moral underpinnings serve to remind us that with pleasure, comes pain, guilt, suffering, and malaise. The preoccupation with universal themes rescues Shaw's paintings from being merely decorative and elevates them to the mantle of history painting.

Raqib Shaw first encountered Western art at the age of sixteen at the National Gallery on a trip to London. He came upon such masterpieces as Hans Holbein's The Ambassadors (1533) that made a profound impression on him.  The double portrait painting by Holbein is accompanied by a still life of meticulously rendered objects. The meaning of these objects, what they signify and their symbolic imprint has been the cause of heated academic debate. Paintings made during the Medieval and Renaissance eras were replete in moral implications. The rich attention to detail, the use of signifiers to unfold narrative and the proliferation of symbols to confound meaning are devices common to both Holbein and Shaw and they use it to unlock complex questions about morality and social norms. It is interesting to note that Holbein lived in an age when there was little distinction between the decorative and fine arts.

The double portrait painting by Holbein is accompanied by a still life of meticulously rendered objects. The meaning of these objects, what they signify and their symbolic imprint has been the cause of heated academic debate. Paintings made during the Medieval and Renaissance eras were replete in moral implications. The rich attention to detail, the use of signifiers to unfold narrative and the proliferation of symbols to confound meaning are devices common to both Holbein and Shaw and they use it to unlock complex questions about morality and social norms. It is interesting to note that Holbein lived in an age when there was little distinction between the decorative and fine arts.

It's certain that Shaw's exposure to Medieval and Renaissance art fortified his visual thinking, helped him to develop a conceptual framework for painting and deepened his relationship to the history of art. These initial imprints were to form the core of his exploration into subject matter, material and style even later on at Central Saint Martins. In portraits completed in 2006, Shaw has paid homage to Holbein's iconic portraits of Henry VIII and wives Jane Seymour and Anne of Cleves and morphed them into part-animals, playfully embellishing upon their features with his own signature style. Although centuries have passed between the time of Holbein and Shaw, the focus for Shaw is on symbolism, and his appropriation of the Old Master is in reverence of the eternal language of symbols and what they communicate. Decadence, extravagance, moral decrepitude lie at the heart of Shaw's concerns as they did for his artistic predecessors.

Shaw maintains a detached relationship with the country of his origin. In fact he speaks very little about his background. He was born in Kolkata into a family that dealt in carpets, shawls and jewellery. But when six months old his family moved back to Kashmir where he grew up. Winters however were spent in Kolkata. Shaw apparently was often left to his own devices. Not having many friends or television for entertainment, he spent much of his time on his own. In the long, drawn out hours, he lost himself in endless daydreams and found some solace in reading English classics.

The receding colonial dream still had its strains in Kashmir, and the young Shaw found relational similarities between the attitudes and modes in Kashmir and those scripted in his favourite novels like Wuthering Heights. At the age of 8, Shaw started to paint after school. It appears that even in his pre-adolescent years, painting provided a means for Shaw to channelize his fantasies and create alternate universes. Raqib Shaw's ambivalence about his past is no doubt tied to his relationship (or lack thereof) with his family. It is likely that his homosexuality played a part, as did perhaps his choice to pursue art as a career against his family's wishes. According to sources that know Shaw, he now maintains few personal ties to India. His constant references to India allude instead to the rich diversity of aesthetic experiences and philosophies that have informed his art making. He cites the influence of Persian miniatures, carpets, shawls, jewellery, Buddhism, Kama Sutra and Sufi music as being as important as those gleaned from the European tradition of painting.

In 1998, Shaw moved to London and worked for a brief time for the family business out of a retail store in Mayfair. However, he soon discovered that selling carpets and shawls wasn't his preferred vocation. Upon quitting the business (a move that apparently forced him to sell out his shares back to his family), he moved to a humble studio apartment in London and entered Central Saint Martins to study fine art. Shaw graduated in 2001 and followed on with an MA in Fine Art from the same college in 2002. Although he describes this time as the happiest in his life, he came into a hostile environment at Saint Martins. Shaw was a misfit. According to Shaw, his peers liked to view him as a kind of 'noble savage' who had to be taught about contemporary art. His penchant for the traditional canons of Medieval and Renaissance painting didn't help matters either.

By the late 1990's, painting was considered to be a 'dead' medium. The popular notion of the day was that painters could never come up with something new. Conceptual art was fashionable; painting was passé. In spite of this, Shaw persevered. For two years he experimented with the painterly medium in search of a new kind of painting. He painted in oils at first, making very precise portraits like the ones he saw at the National Galleries in London. However, no matter how hard he tried, he couldn't get his paintings to not look like copies of Botticelli or Michelangelo. Realizing that he could not (and did not) want to compete with the history of painting, he moved away from using oils and began to study industrial materials. He wanted to retain the painterly qualities of using oil, but switching to materials more tailored to our times enabled Shaw to make paintings that engaged in a dialogue with the history of painting and at the same time reflect on present- day concerns.

For his final show at Saint Martins, Shaw produced two distinct bodies of work. There were mainly portraits, and smaller, erotic drawings done in pencil. One of the paintings was of the Queen. While the Queen of England has been painted by every major British artist and attempted by many other minor ones, Shaw's Queen was not a representation but a symbolic gesture for which Shaw used the portrait paintings of Elizabeth I at the National Portrait Gallery as a point of departure. “I wanted to choose a motif,” Shaw said at that time, “I wanted to find a subject with that sort of over-the- top campness…it was more about what a portrait of Elizabeth I in our day and age could be.” The drawings were structurally similar to the paintings but were concerned with an overt sense of eroticism. Glenn Scott-Wright, co-Director of Victoria Miro Gallery a premier gallery for figurative art in London expressed interest in Shaw's work when he saw it at the final year show. However, as Shaw had been selling his work from his studio since his second year at college, he didn't have enough works for an exhibition straight away. Instead, he spent a year after graduation integrating the two dominant strands in his work. It was only after leaving Central Saint Martins and while working towards his first solo exhibition at Victoria Miro Gallery that Shaw was able to bring together in one format, the painterly figuration of the portraits with the implosive energy of the erotically charged drawings to create the massive, life-affirming, hallucinogenic portrayals of human desire seen in Garden of Earthly Delights.

“I wanted to find a subject with that sort of over-the- top campness…it was more about what a portrait of Elizabeth I in our day and age could be.” The drawings were structurally similar to the paintings but were concerned with an overt sense of eroticism. Glenn Scott-Wright, co-Director of Victoria Miro Gallery a premier gallery for figurative art in London expressed interest in Shaw's work when he saw it at the final year show. However, as Shaw had been selling his work from his studio since his second year at college, he didn't have enough works for an exhibition straight away. Instead, he spent a year after graduation integrating the two dominant strands in his work. It was only after leaving Central Saint Martins and while working towards his first solo exhibition at Victoria Miro Gallery that Shaw was able to bring together in one format, the painterly figuration of the portraits with the implosive energy of the erotically charged drawings to create the massive, life-affirming, hallucinogenic portrayals of human desire seen in Garden of Earthly Delights.

The technique Shaw devised is unique. The initial drawing is done first on a wooden board. The edges of the drawing are then raised with stained glass paint from Switzerland that is commonly used to repair stained glass in chapels. It creates a solid barrier like a buffer dam. The enamel and metallic industrial paint mixture is then poured into the spaces between the outlines and then the paint is manipulated to the desired effect by a porcupine quill to meticulously enhance detailing. The quills give him a perfect blend of flexibility and control (he earlier used needles but it was extremely tedious and time-consuming). The technique is similar to those found in early Asian pottery and is painstakingly laborious.

Shaw works on a flat, horizontal surface, moving from the middle of the composition to the outer edges. As the paint mixture has a fast-drying time, it is crucial that Shaw work on only small sections at a time and build the picture frame by frame. Shaw himself sees the finished painting only once it is complete and the work is up.

Each painting can take a span of a few months to finish. The Garden of Earthly Delights III is made with synthetic polymer paint, glitter, rhinestones and gems on board and reportedly took nine months to complete. The enamel paint creates a luminous glow; the glitter, rhinestones and gems sparkle. A myriad of images, patterns and colours scintillate the senses. The whole painting comes to life in a twinkle of an eye.

The process of painting is of key significance for Shaw. He becomes totally immersed in the painterly activity, losing himself in the deft play of material and narrative. It's this process of 'getting lost' that allows Shaw to delve deeper into a subconscious realm from where the most palpable of desires emerge and take form through drawing and painting. Music is essential too. For a time, Shaw listened to Sufi music while he painted which put him in a kind of trance, moving him further inward, away from the real, material world and into a kaleidoscope of fantasies. Devising a new and undiscovered working method was to be the key for Shaw in unleashing a torrid stream of images that together create a narrative that subverts popular, widespread and established notions about social acceptability. Shaw's sexuality, its complex machinations, and his layered negotiations with society from the time of his youth take center stage in the drama played out in his canvases. The paintings are sociological as much as they are personal documents. Like Bosch before him, the boundary between moral reasoning and carnal pleasure dissolves in a vivid display of fantasy and sensation in Shaw's paintings. It turns the rest of us into voyeurs, guilty of participation in the sadomasochistic free-for-all.

To create the vast, minutiae of the underwater worlds depicted in the Garden of Earthly Delights, Shaw spent countless hours at the Natural History Museum poring over old books and illustrations of aquatic life forms. Around this same time, Shaw became keenly aware of Japanese art. A Japanese friend also introduced Shaw to Japanese lacquered screens (Byobu) and the art of wedding kimonos (Uchikake), both of which Shaw draws upon as visual references in his work. He also painted pastiches inspired by the nineteenth-century printmaker Hokusai and created many studies of roses and flowers. Like Hokusai, Shaw didn't want to merely paint flowers; he sought to capture the feeling of the wind through the petals.

Shaw is acutely aware of the beauty of his works, but he is quick to emphasize the presence of feeling as the necessary antecedent for beauty in art. It's interesting to note Shaw is a solitary figure, preferring the exclusive isolation of his studio to the active social circuit of London's art world. The loneliness of his childhood finds expression in adulthood. The near narcissistic characters that emerge from Shaw's watery worlds, while they vibrate amid shoals of fish and plethora of sea urchin and coral reef, are instinctive self-portraits. In this dense habitat of his own making, Shaw finds a world that is of a dizzying kind of beauty, one that can only be borne only through silent meditation and a heightening of the senses. By the calling forth of feeling from the deepest recesses of the human psyche, Shaw's constructs sexed-up utopias where pain and pleasure are availed of in equal measure. In 2004, Shaw's solo exhibition at Victoria Miro Gallery was received to critical and popular acclaim  and it also travelled to Deitch Projects in New York in 2005. The British art world sat up and took notice of the young artist who was re-imagining the history of European painting but with eclectic influences.

and it also travelled to Deitch Projects in New York in 2005. The British art world sat up and took notice of the young artist who was re-imagining the history of European painting but with eclectic influences.

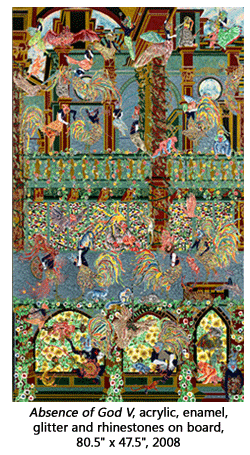

Shaw is currently represented exclusively by White Cube, a blue-chip gallery in London that has on its roster, the likes of Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Chuck Close. A painstakingly methodical painter, his last solo exhibition Absence of God was at White Cube in 2009; it was his first gallery show after the Deitch Projects show in 2005. White Cube proudly announced their latest recruit in 2008 to the art world at Art Basel in Switzerland, the king of all fine art trade fairs that is graced by every major art collector in the world. Visitors saw a sparkling new gem of a work called Absence of God I (2007) adorning the outer wall of White Cube's booth (a location that gets the greatest viewing exposure). The work distilled the themes of Shaw's former series, but had a compactness of style, thematic content and materials used that shows a developed artistic and conceptual maturity. In this painting, a red winged skull in resplendent regalia (it also looks like a phallus!) takes the place of God in the altar of a splendid Gothic interior. The presence of the skull evidences a major trope of European painting called “memento mori”, whereby the themes of mortality and the transience of life are engaged. Painted with acrylic paint, industrial paint, glitter and embedded with semi-precious crystals, the painting literally looks like a priceless jewel. (It sold for a reported £750,000).

There's no doubt that Raqib Shaw has carved out a singular niche for himself in the treacherous terrains of the global art world that can sometimes swallow talent as fast as it discovers it. With a slew of museum exhibitions already under his belt and more on the way, the bluest of blue-chip gallery backing him, and adoring collectors who swear by his work, Shaw is getting the kind of endorsement he needs to be a long-term player in the art world. Raqib Shaw may be elusive but his ecstatic visions are utterly seductive with their irresistible blend of debauchery and irreverence.

Image Courtesy: Jay Jopling/White Cube & the Author