- Prelude

- Editorial

- Subodh's 'return home'

- A Conversation with TV Santosh

- It's a War Out There

- Raqib Shaw

- Illusions in Red from a very British Indian Sculptor

- Stand Alone: Shibu Natesan

- Reading Atul Dodiya

- Bharti Kher: An Obsession for Bindis

- Bose Krishnamachari

- The Image - Spectacle and the Self

- From Self-depiction to Self-reference: Contemporary Indian Art

- GenNext: The Epitome of New Generation Art

- Kolkata's Contemporary Art A Look in the Mirror

- Innovation Coalesced with Continuing Chinese Qualities

- Kala Bhavana-Charukala Anushad Exchange Program

- Montblanc Fountain Pens

- Dutch Designs: The Queen Anne Style

- Bangalore Dance Beat

- Decade of change

- Distance Between Art & It's Connoisseur

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- 3rd India Art Summit

- New Paradigms of the Global Language of Art

- Black Brown & The Blue: Shuvaprasanna

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Printmaker's Season

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- The Pause of Profound Stillness

- Previews

- In the News

- The Rebel Queen: An icon of her own times yet looked down upon

ART news & views

Subodh's 'return home'

Volume: 3 Issue No: 14 Month: 3 Year: 2011

Creative Impulse

by Vinod Bharadwaj

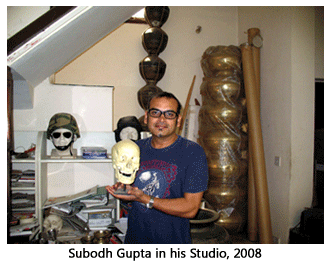

Even during his 'angry' phase poet Shrikant Verma had expressed the longing to 'return home' quite poignantly in one of his famous poems. The poet wanted to return home and burn out slowly in the mahua forest, like a cow-pat. One can sense the same kind of longing to return home in Subodh's art. This longing by itself does not lend significance to an artist. But Subodh has managed to give expression to this longing to 'return home' during successive phases of his art in the form of an extended art experience.

Even during his 'angry' phase poet Shrikant Verma had expressed the longing to 'return home' quite poignantly in one of his famous poems. The poet wanted to return home and burn out slowly in the mahua forest, like a cow-pat. One can sense the same kind of longing to return home in Subodh's art. This longing by itself does not lend significance to an artist. But Subodh has managed to give expression to this longing to 'return home' during successive phases of his art in the form of an extended art experience.

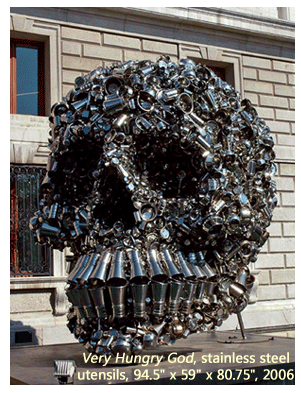

Subodh has transformed the vessels associated with the Indian middle class into an exalting art experience. In my poem Ichchha [Desire] I once visualised the lota [bowl] as a deep and poignant symbol of ordinary Indian life. In 1979, at an exhibition of Jagdish Swaminathan's works at Dhoomimal Gallery in Delhi, a programme of poetry-reading was also included. That's where I first read out Ichchha. Later I came to see in objects such as a glass, a frying pan or a bowl, larger metaphors of life. But if as a poet you sit down to write a series on a variety of vessels, your ability to express yourself might lose its edge. But an artist's canvas is larger than a poet's. He is not bound by such a constraint on expression. That's the reason Subodh has managed to perceive in the 'glitter of the world of steel vessels' a different kind of dream and reality.

Excerpts from a conversation with Subodh Gupta:

Vinod Bhardwaj: When and why did you start work on the series on vessels associated with a middle-class kitchen?

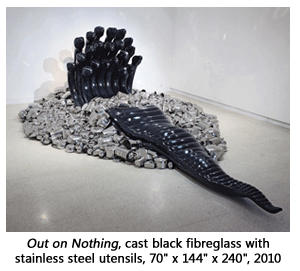

Subodh Gupta: I have been working on the series for some five or six years. In my solo exhibition at the  Gallery Chemould in Mumbai in 1998 I had employed vessels extensively. It's a long story. Whenever I work on theme, I tend to take objects from workaday life whether it's cow dung, or a string-woven stool or vessels etc. One notices that 90 per cent of India's population uses steel vessels. In nearly every Indian household the kitchen is something like a temple. In Hindu households, the kitchen holds the same status as a place of worship. The morning invocation begins with a thali. This is evident in all classes, rich or poor. Cow dung or the string-woven stool are 'earthy material' whereas steel, on the contrary, has this glitter. Some 25 or 30 years ago brass vessels began to disappear from our households. At the same time steel vessels were gaining in popularity, thanks to a variety of attractive schemes. Indeed serving food in steel vessels became a status symbol. I strongly remember all these things. The Gallery Chemould show even had a life-size cow made of fibreglass. There were steel vessels as well and a pride of place for a country made pistol.

Gallery Chemould in Mumbai in 1998 I had employed vessels extensively. It's a long story. Whenever I work on theme, I tend to take objects from workaday life whether it's cow dung, or a string-woven stool or vessels etc. One notices that 90 per cent of India's population uses steel vessels. In nearly every Indian household the kitchen is something like a temple. In Hindu households, the kitchen holds the same status as a place of worship. The morning invocation begins with a thali. This is evident in all classes, rich or poor. Cow dung or the string-woven stool are 'earthy material' whereas steel, on the contrary, has this glitter. Some 25 or 30 years ago brass vessels began to disappear from our households. At the same time steel vessels were gaining in popularity, thanks to a variety of attractive schemes. Indeed serving food in steel vessels became a status symbol. I strongly remember all these things. The Gallery Chemould show even had a life-size cow made of fibreglass. There were steel vessels as well and a pride of place for a country made pistol.

VB: The countrymade revolver is a key metaphor in Bihar today.

SG: While living in Delhi I always cherished the memories of home. My middle brother lived in Jamalpur near Monghyr, an area where criminals rule the roost. He told me he too owned such a revolver. Around that time I also read a report on countrymade revolvers in the weekly Outlook. I gathered that one could get one for two to three thousand rupees or even less. I took the idea of the 'form' of the revolver from Outlook itself to make a cast in clay. When you lift two or three 'iconic images' - the cow, the steel vessels and the revolver - a whole host of meanings comes into play. One characteristic of my work has been that I bring together two or three objects and then try and create a unified work.

VB: What inspired you to use the luggage carried home from the airport by returning Indians as creative material?

SG: For many years I had observed at airports the Indians returning home from Dubai, Kuwait and elsewhere. I always found them carrying the luggage of an unusual nature. Their suitcases, bundles or packages all stood out. I had never seen such packing before and found it quite attractive. Sometimes I would get talking to the people carrying them. The packages also roused curiosity about their contents. What might they contain? Each package encompassed a family's hopes as it were. At the airport I would take a variety of photographs of everything that I noticed and it was with the help of those images that I subsequently made paintings and sculptures and mounted installations.

VB: Once, as I was on my way back from Italy, on the plane I had this man sitting next to me. He was wearing many numbers of watches on both his wrists and nursing a five-litre bottle of Scotch between his legs. It was quite a poignant installation in itself. Such memories can certainly be transformed into an art experience.

Why were you drawn to the look and body of the Ambassador car?

SG: In an age when you see grand-looking limousines everywhere, I still consider the Ambassador as the best car for Indian roads and I visualise its body as symbolic of an Indian.

In India the Ambassador has also found favour with the politicians, businessmen and tourists. And foreigners too are drawn to this 'classical' model. All kinds of models have come and gone but none has succeeded in beating the Ambassador's design. In the context of the Indian social reality even the red light displayed atop an Ambassador has its specific meaning. Indeed it's an icon. Just as in a village the shoulder towel would be. Everything associated with the Ambassador attracts me its look, its form everything.

VB: You work in a variety of mediums. Immersed in your art you now transform yourself into an actor, now into a director or an artist… Why, as for being an artist you've always been one.

SG: I don't hesitate to use any medium, whether it's video, performance, painting, sculpture or installation. Or even acting. In Patna, for five years I performed in the theatre. When my friend, filmmaker Tigmanshu Dhulia, offered me a role in his film Haasil, I grabbed it. The film was centred around campus politics in a university. I played the sidekick of a big boss. Given an opportunity, I would love to do such roles again.

VB: Would you also like to be a director?

SG: No, I only like to act. Even in the theatre I would never play the hero. I only took character roles. I would often land the second 'major' role - a deranged character, a soldier, an army major or a transsexual . . . any such role.

VB: In 1999, in Modinagar, your body installation during the workshop Khoj was a subject of debate.

SG: That area was close to the countryside. I would go to a village six km away, taking with me the headman's son so it would be easy to meet people and talk to them. There I fell under the spell of neat courtyards coated in cow dung and the aroma of saag cooking in earthen pots on a fire fuelled by cow-pats. I would visit each house and ask for an object. It could be any object, no matter if it was old and used or newly-bought. I collected the objects for 13 days. I also took photographs of the givers. Then I had this feeling that I was a journalist, not an artist. Where did those objects come from in the first place? I thought of earth, of land. I thought I should seek out the places where those objects had come from. I chose a spot which was a stage and placed myself in the middle of it. I lay down on the bare earth in the manner of seers and mendicants who assume similar postures after smearing themselves with ash. If some other person were to lie down like that, perhaps no one would have noticed. But because it was an artist called Subodh Gupta, the viewers were surprised.

VB: What was the inspiration behind the Pure video?

SG: The cow, cow dung etc. were already part of my artistic vocabulary. Sheela Gowda has also done a large body of work by applying cow dung. So somewhere inside me I was already under the spell of this medium. I felt I too could use it to perhaps come up with a different kind of work. As a child I had watched my mother prepare for the Satyanarayan Katha by putting together mango leaves, grass, cow dung etc. Cow dung has its own realism. It is supposed to be an antiseptic on account of its purity. The wheat is dried in villages after first coating the ground with cow dung. In villages I had seen that for the sake of purification the high-caste families would put a dab of cow dung on the tongue of their children when they returned home after supping with the children of the lower castes. The video was made at a performance at the Khoj workshop with the camera assistance of Monica Narula. It was a seven- or eight-minute video and ends at the elevator, after the bath. The elevator is the fast track of contemporary life. This link is important. When we take a bath the water does not purify us. The cow dung does. In the setting of a metropolis like Delhi I was trying to understand and fathom the link between the process of taking bath in a middle-class flat, of purifying oneself, and the fast track of an elevator. I consider this work an important step in my career.

VB: Krishen Khanna has drawn paintings inspired by bandmasters. Where did your inspiration come from?

SG: I hadn't seen Krishen Khanna's paintings at the time I made mine. I would sometimes watch from the Patna Arts College hostel biers being carried to the cremation ground.  On occasion, the procession would be accompanied by bandmasters. They were a familiar sight at marriage functions anyway. I was also quite impressed by the contradictions inherent in the bandmasters' uniforms. They'd be dressed in glittering clothes, play shining bands but would be walking in rubber slippers. And even the slippers would be quite worn, offering little respite to their chapped heels. More than portraying them as they played their instruments I would draw them when they were in the middle of having tea etc. Maybe one day I would again return to work on this series.

On occasion, the procession would be accompanied by bandmasters. They were a familiar sight at marriage functions anyway. I was also quite impressed by the contradictions inherent in the bandmasters' uniforms. They'd be dressed in glittering clothes, play shining bands but would be walking in rubber slippers. And even the slippers would be quite worn, offering little respite to their chapped heels. More than portraying them as they played their instruments I would draw them when they were in the middle of having tea etc. Maybe one day I would again return to work on this series.

VB: Is there any particular phase of your work which you find more memorable or more significant?

SG: Everything has significance for me. An artist finds joy only when he is out on a voyage of discovery. The day you succeed in discovering yourself as well as your art that would be the day to remember. I am realising this joy now. It is very difficult to fathom and assimilate art. The feeling is akin to discovering a treasure. I don't yet know if I've found this treasure. In '96, when I put up my first installation with a string-woven seat at the centre of it, I felt that was a highly important step for my art. Even today, when I create a work, I go back to the memories of my home. I try to discover myself. That first installation had memories of 21 mornings - memories precious to me.

VB: How do you feel today, having tasted success at the international level?

SG: I feel happy. I also enjoy this success. I have this feeling that this is just the beginning, but I do not want to fritter myself away. I try to recall those of my creations which were liked by viewers. But by nature I am greedy. The priest is never content no matter how much he is fed. This greed has not exhausted yet.

VB: Obviously this greed inspires creativity, which forms the essential identity of an inspired artist.

-Translated by Brij Sharma

Original Hindi version was published in the book cum catalogue of Subodh Gupta for Venice Biennale 2005

Photo courtesy Vinod Bhardwaj