- Prelude

- Editorial

- Subodh's 'return home'

- A Conversation with TV Santosh

- It's a War Out There

- Raqib Shaw

- Illusions in Red from a very British Indian Sculptor

- Stand Alone: Shibu Natesan

- Reading Atul Dodiya

- Bharti Kher: An Obsession for Bindis

- Bose Krishnamachari

- The Image - Spectacle and the Self

- From Self-depiction to Self-reference: Contemporary Indian Art

- GenNext: The Epitome of New Generation Art

- Kolkata's Contemporary Art A Look in the Mirror

- Innovation Coalesced with Continuing Chinese Qualities

- Kala Bhavana-Charukala Anushad Exchange Program

- Montblanc Fountain Pens

- Dutch Designs: The Queen Anne Style

- Bangalore Dance Beat

- Decade of change

- Distance Between Art & It's Connoisseur

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- 3rd India Art Summit

- New Paradigms of the Global Language of Art

- Black Brown & The Blue: Shuvaprasanna

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Printmaker's Season

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- The Pause of Profound Stillness

- Previews

- In the News

- The Rebel Queen: An icon of her own times yet looked down upon

ART news & views

Illusions in Red from a very British Indian Sculptor

Volume: 3 Issue No: 14 Month: 3 Year: 2011

by John Elliott

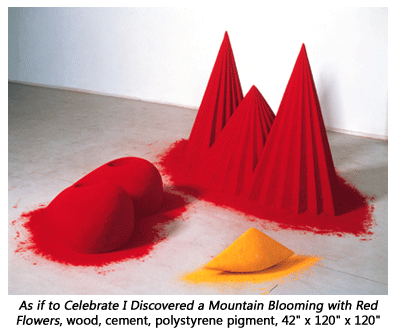

What is it that makes Anish Kapoor, the 57-year old India-born British sculptor, so successful? When I first saw his works at London's Royal Academy in November 2009, I was bemused, wondering whether this rich and famous artist was playing a trick on us all with his dramatic collection of materials, shapes and colours,.

Listening to him since then in snatched conversations, and when he has spoken at various events in Delhi, I have gradually realised the depth and vision that leads to his vast mixture of large dark red wax installations, piles of bright red and yellow pigments, deep blue and yellow walls, and his amazing array of environment -transforming work that ranges from Cloud Gate,  a 100-ton mirrored sculpture in Chicago, to a huge red trumpet-like funnel in a hill overlooking the New Zealand coast.

a 100-ton mirrored sculpture in Chicago, to a huge red trumpet-like funnel in a hill overlooking the New Zealand coast.

He likes his works to puzzle and confound. “As Homi Bhabha says, they 'provoke a slight anxiety that it isn't quite what it is' ”, he said, quoting the cultural theorist during a walk-through at his spectacular show in Delhi's National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) earlier this year. “Art is all about illusion.....I've never believed in realism in art”.

Later during a conversation at Delhi's Art Summit, Bhabha said that the “beauty of these works is that something vital, if unknown, is caught the notion of anxiety is so important”. The two men are old friends and often have these sorts of debates. Kapoor agreed: “One has to dare to not know only then can space be properly created. I'd rather not know and deal with the anxiety”.

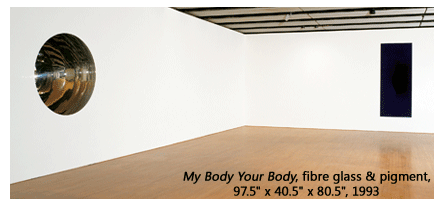

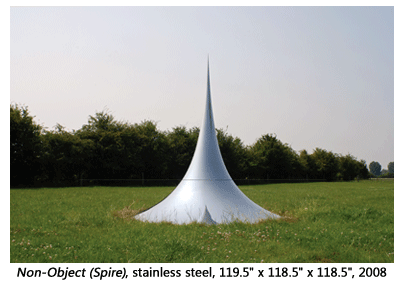

During the walk-through, someone asked him: “Do you want me to be destabilised, to be broken down and have to rebuild?” “Precisely,” came the triumphal reply, with a smile. Looking at a large silver mirror that constantly changes reflections as the viewer moves one moment you are upside down and the next you are not - he says, “It invites vertigo as if you are falling into the object”. That fits with his view that “abstract art goes to the beginnings of consciousness, which figurative art can't”.

Kapoor originally thought about being an engineer and studied electrical engineering. That background comes through in the way he uses his materials, shunning theorists who told him to be true to “steel as steel and stone as stone”. It took him ten years to learn how to produce his mirrored objects so that, as he puts it, “they engage with space.....there is something unknown (saying) let me pull you in”. He sees a parallel with the “sculptured construction”  of poems where “you can almost feel the nuts and bolts in the construction”. But he insists he does not have an agenda. “I don't have a series of things I'm trying to say”.

of poems where “you can almost feel the nuts and bolts in the construction”. But he insists he does not have an agenda. “I don't have a series of things I'm trying to say”.

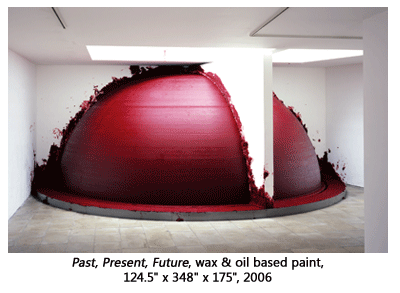

Kapoor has the reputation of being gruff and moody, but that morning in the NGMA, he was relaxed and clearly enjoyed explaining his art. He said that red was his favourite colour something that we could see because of his red mirrors, wax and pigments. “It's a colour that leads to darkness.......red does darkness like nothing else does”. He worked in dark red wax because “my real interest is in the colour and the way it is transferable”. He wanted something more akin to oil paint, and admitted there was “some association with blood and meat”

Kapoor talks a lot about his use of colour when discussing the Indianness of his works because, inevitably, the question that he is asked most is what influence India has had. “Red is a colour I've felt very strongly about,” he said in a 2003 BBC interview. “Maybe red is a very Indian colour, maybe it's one of those things that I grew up with and recognise at some other level. Of course, it is the colour of the interior of our bodies. Red is the centre.”

His views on his Indianness can be controversial. He said in Delhi last November that he has “internalised and mythologised” India, and undoubtedly the richness of India is reflected in his bright basic reds, blues and yellows. Maybe, though, that was a rationalisation to fit in with where he was. He is certainly very conscious of his roots. Now a Buddhist, he was born in Mumbai to an Indian Hindu father and a Baghdadi Jewish mother, was educated at India's ultra-elite Doon school, and worked on an Israeli kibbutz before going to art school in London. He has lived in the UK since 1973, has taken British citizenship, and paid only occasional private visits to India till his twin exhibitions opened in Delhi and Mumbai last November.

In London during the RA show, I heard that he was not very proud of being Indian, indeed that he played it down, preferring the life and accents of the UK. Certainly, that was true some years ago, as Ian Findlay-Brown, who runs the bi-monthly Asian Art News in Hong Kong, confirms. He asked Kapoor for an interview in the mid-1990s, explaining that his then-new magazine wanted  to write about Asian artists. Kapoor's refusal was curt: “He told me 'I'm a British artist, not an Asian artist',” says Findlay-Brown.

to write about Asian artists. Kapoor's refusal was curt: “He told me 'I'm a British artist, not an Asian artist',” says Findlay-Brown.

When I first asked Kapoor to explain the Indianness, he replied that was “the one question I shall avoid answering”. Later at a dinner, he was more expansive, explaining that he did not want to tackle the question because it was “a struggle as a non-western artist not to be labelled” with one's country of origin. “I'm Indian, My sensibility is Indian. And I welcome that, rejoice in that, but the great battle nowadays is to occupy an aesthetic territory that isn't linked to nationality”.

In conversation with Bhabha, Kapoor said he had “resisted over the last 25 years looking at work through an Indian lens”. That had been “a fruitful struggle important for me to do”, but now he was relaxed on the subject. He thought it was “not very helpful” to have a nation-specific view and contrasted that with Salman Rushdie, the author and a friend, who brought India into most of his books. “He carries in himself an eternal Indian,” says Kapoor.

Irrespective of all this, Kapoor was treated as a hero at his Delhi and Mumbai exhibitions. “Finally, the art world's most theatrical exponent is coming home Return of the Prodigal,” said one headline “An artist returns to his roots” and “Anish comes home” said others. Sonia Gandhi, leader of India's governing coalition, opened the Delhi show and said in her speech that she regretted that India's public spaces had so little public art of any real distinction. She hoped that one day there would be a Kapoor installation in an Indian city, as well works by others. (Talks are now in progress on a possible Kapoor sculpture, and one has been commissioned for Delhi from Subodh Gupta, a leading Indian contemporary sculptor).

Moving on from Indianness, Kapoor told me that the most important thing was what he and viewers see when "looking in”. Shooting into the Corner, where an iron cannon shoots sticky splodges of red wax across a room every 20 minutes, illustrates this. When I watched the gun with an Indian friend and a crowd of other visitors at Kapoor's RA show in London, we were bemused, not quite seeing the point. People giggled, wondering whether to hang around for 20 minutes until the next split-second blast.

bemused, not quite seeing the point. People giggled, wondering whether to hang around for 20 minutes until the next split-second blast.

At the time, Kapoor seemed to dismiss the gun, saying it was “almost a cliché - the artist just throws a bag of paint at a canvas and there it is”. But when it started firing in Mumbai a year later, just after the second anniversary of the city's devastating 2008 terrorist attacks, it was seen as symbolic of the repetitive shooting and horrors of terrorism. That led Kapoor to toughen up his interpretation and say that the red colour was “full of darkness and danger”, echoing his point that he is drawn by the depth of the wax colour. He admitted it was “truly political”, but insisted it had “no agenda”, adding that art can “take on the context of the bigger world”.

Similarly, many RA visitors did not understand a massive tracked train-like block of blood-red wax, weighing more than 20 tons, that squeezed and oozed its way down tracks and through a doorway linking two galleries. The Jewish Chronicle saw “references to blood and railways” that “must surely have a link to Holocaust” trains that carried Jews to concentration death camps. I asked Kapoor about this and he answered: “Yes, train if you like and terrorism if you like”, adding: “Yes of course it will mean something else in Mumbai. These things change all the time and I like that”

That RA show was the most impressive and important exhibition of his career. He was the first artist to be given all the galleries to display his works that ranged as did those that came to Delhi and Mumbai last November - from smallish shimmering and reflective glass, mirrored and steel shapes, through piles of pigments, to large symbolic mounds of muddy-looking dark red wax.

Kapoor was listed in The Times of London's Rich List early in 2009 with wealth of £20m. Homi Bhabha asked him whether the art market came into the studio. “I don't see any conflict.” said Kapoor, “part of the object is to make money”. They agreed, one as a psychologist and the other as an artist, that the more depth one went into a subject, the higher the price that could be charged.

The Times reported that Kapoor's company, White Dark, showed an operating profit of £17.2m in 2008, up from £8.4m the previous year. He has several homes including one in the UK and one in the Bahamas. In London's Chelsea, there is what The Times described as a “glass, stone and shimmering stainless steel” structure.

Kapoor's works are costly.  A curiously tangled 370ft high steel structure, The Orbit, that he is building for London's 2012 Olympics will cost £19m (Rs135 crore). Lakshmi Mittal, the Indian-born businessman who lives in London, is donating £16m, and the work will officially be called Arcelor Mittal Orbit after the world's largest steel company that he runs. The famous Chicago sculpture, which is said to be the world's most visited public artwork cost £14.3m. It is a massive bean-like stainless steel shape that reflects its surroundings including people, buildings and the sky, with a ground-level arch to walk through.

A curiously tangled 370ft high steel structure, The Orbit, that he is building for London's 2012 Olympics will cost £19m (Rs135 crore). Lakshmi Mittal, the Indian-born businessman who lives in London, is donating £16m, and the work will officially be called Arcelor Mittal Orbit after the world's largest steel company that he runs. The famous Chicago sculpture, which is said to be the world's most visited public artwork cost £14.3m. It is a massive bean-like stainless steel shape that reflects its surroundings including people, buildings and the sky, with a ground-level arch to walk through.

“Every successful economy needs a tangible celebration,” Rajeev Sethi, a leading promoter of India's arts and artists, told me a few years ago when I was writing an article on the then newly booming art market for the Royal Academy Magazine. He was referring to the huge success being enjoyed by artists old and young, famous and not-yet-famous, in those days of rocketing art prices. None of these artists of course has got to the financial heights reached by Kapoor who is a leader of that celebration. And he must be an inspiration for those who dream of going abroad, absorbing foreign experience and knowledge, and then returning as an international icon.

John Elliott is a British foreign correspondent who has lived in India for 20 years. His writes a blog, Riding the Elephant, http://ridingtheelephant.wordpress.com

Image courtesy the artist