- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Sheela Gowda

- The DIY Artist with a Mission

- Discovering Novel Horizons

- A Conversation with Raqs Media Collective

- Manjunath Kamath

- Jitish Kallat- the Alchemist

- The Artist and the Dangers of the Everyday: Medium, Perception and Meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work

- An Attitude for the Indian New Media

- Weave a Dream-Theme Over Air or a Medium like Ether

- Installation in Perspective: Two Outdoor Projects

- Towards The Future: New Media Practice at Kala Bhavana

- Workshop @ Facebook

- Desire Machine: Creating Their Own Moments…

- Typography: The Art of Playing with Words

- Legend of a Maverick

- Dunhill-Namiki

- The Period of Transition: William and Mary Style

- The Beauty of Stone

- Nero's Guests: Voicing Protest Against Peasant's Suicides

- Patrons and Artists

- The Dragon Masters

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Winds of Change

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- In the News

- Previews

- Ascending Energy, Merging Forms: Works by Satish Gujral

- Re-visiting the Root

- The Presence of Past a New Media Workshop

- Taue Project

ART news & views

A Conversation with Raqs Media Collective

Volume: 3 Issue No: 15 Month: 4 Year: 2011

by Saba Gulraiz

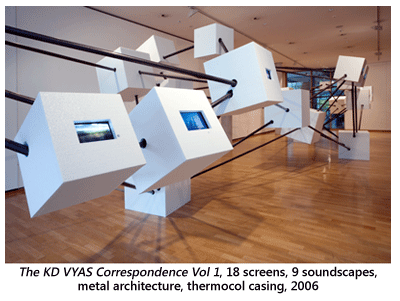

Raqs Media Collective is a unitary body of three creative young people including Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. Sarai and OPUS are their other two important initiatives. In conjunction with the Centre for the Study of Developing Society, Raqs has established Sarai, a platform that offers independent research and residency programmes. OPUS, an Open Platform for Unlimited Signification, offers a free online space that opens up an avenue for the flow of creative ideas. Raqs expands a wide range of collective endeavors which includes documentary filmmaking, photography, new media art, historical enquiry, philosophical research and theory and curation. Embracing all the unlimited possibilities that the new media offers, they are incessantly exploring new ways of engaging audiences into interactivity. Their creative genius interpenetrates into social, political, cultural and personal conditions of the contemporary living and prepares a ground for alternate discourses. Both their visual and theoretical practice offers them a distinct presence in the global space of art and culture.

Saba Gulraiz: What inspired you to christen your group as Raqs?

Monica Narula: We were students together in Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi and there we approached the idea of making images in a way quite different from other people. So, when we passed  out from Jamia we decided that we would formalize that. Then we thought to name it Raqs for we found the word very interesting as it's used for the state that whirling dervishes enter into when they whirl in ecstasy. For us it's “kinetic contemplation” because perhaps in this whole idea that your thinking, your making, your working and your being all are connected together. That's why we liked the word a lot and we still like it. The reason we used the word Media was because in early 1990s when it was going to envelope the whole world and some people wanted to be film people, we wanted to open ourselves to any imaginable media possible. Also, we strongly believe in the idea of working together that makes us philanthropically and poetically complete so, we are collective.

out from Jamia we decided that we would formalize that. Then we thought to name it Raqs for we found the word very interesting as it's used for the state that whirling dervishes enter into when they whirl in ecstasy. For us it's “kinetic contemplation” because perhaps in this whole idea that your thinking, your making, your working and your being all are connected together. That's why we liked the word a lot and we still like it. The reason we used the word Media was because in early 1990s when it was going to envelope the whole world and some people wanted to be film people, we wanted to open ourselves to any imaginable media possible. Also, we strongly believe in the idea of working together that makes us philanthropically and poetically complete so, we are collective.

SG: Would you like to say something about the new media culture in India?

Jeebesh Bagchi: The new media culture when we started working in the late 90s was very different but later it saw a seismic change in the way we communicate with each other. That was the time when one of the fundamental transformations has been the way cultural goods travel and the way we inhabit them and of course the density of mobile phones, DVDs, CDs also created a new cultural landscape or topography of transmission, circulation and alteration of cultural goods and producing a new kind of sensory envelope. There is also a massive obsession of trades and corporations around spoofing, surveillance, security, data basing etc. These are the different fore fields which the new media culture has been shaping rapidly in the last 10-15 years.

SG: Would you like to talk a little about modern consciousness as mediated by technology?

JB: Technology is highly enmeshed in our lives. The way we communicate each other involves a process that is enmeshed in a technological order, it's a kind of produced, received, transmitted, held, archived by the technology. To say that human beings are communicating less or communicating not substantially because they are mediated by technology is not to really capture what the complexity of the contemporary living is. One can have a very complex reading of what technology does, the way it changes or transforms the way we interact with the world. It produces different economies. They may be the economies of production or pleasure. This is one thing that we try to understand but to say that it is bad or good is not my interest. I am more interested in how does it change, what does it do, what possible extension it can produce of the human, when it is possible to separate human and the machine or when it is not possible to separate between human and the machine or when it is fused with human and the machine.

SG: There is always an argument against the excess presence of technology in art, how do you reconcile art practice and technology?

JB: This argument, I think, is not an intelligent or very well formulated argument because technology  has given well formalized tools. The tools of art, whether it's Painting, Drawing, Printing or Sculpting, are the hard core parts of technology. Technology is a ground in which art practice locates itself. The whole question comes when there is too much meditation of technology that the distance between the creator and the object starts disappearing or there is too much distance so that there is no sensuousness, there is no hand involved. That was the kind of critique, but it was a critique that never could be thought-through because in cinema, the area that is well mediated by technology, people have done a lot of amazing work. Though in art it came late but came in a very intelligent and sophisticated way. It took everyone with surprise for initially when you are surprised you oppose it. Now I don't think that opposition exists as such.

has given well formalized tools. The tools of art, whether it's Painting, Drawing, Printing or Sculpting, are the hard core parts of technology. Technology is a ground in which art practice locates itself. The whole question comes when there is too much meditation of technology that the distance between the creator and the object starts disappearing or there is too much distance so that there is no sensuousness, there is no hand involved. That was the kind of critique, but it was a critique that never could be thought-through because in cinema, the area that is well mediated by technology, people have done a lot of amazing work. Though in art it came late but came in a very intelligent and sophisticated way. It took everyone with surprise for initially when you are surprised you oppose it. Now I don't think that opposition exists as such.

SG: Sometimes in the absence of interpretations and statements a New Media work turns into a jigsaw puzzle. Do you also feel building a theoretical framework round a work becomes necessary for audience's reception and understanding?

JB: When you say something, you try to interpret the way you think .Interpretation is not a problem. The problem is whether interpretation is available to you when you are viewing a work in some intelligible form or the interpretation is hiding itself and the artist is trying to show some kind of uncontaminated direct link to something, some reality or his internal life. What we try to do is to play around with the different interpretative frameworks that we receive, that we generate, that we try to argue with, that we try to build up with and play it along with producing a world. The world that we are producing through the art work whether it is objects or some kind of sensation of image or sound or some light we try to create a sense, a sensorium and a field that is much more than interpretation. I think to interpret is also to ask very interesting question of the world and also to make demands of each other as human beings. So, we keep that play on.

SG: How far do you feel you are successful in engaging audiences into more dynamic and meaningful interactions?

JB: Over a period of time, from the last 10-15 years, in our practice we've developed a wide body of people whom we interacted with, who've seen our work and have dialogues with us. It's something that we share across many cities in the world. We've a fair number of people whom we are quite intensely in acknowledgement of their work whether it's a poet, an accountant, a film maker or a layman. We know that somewhere there is a whole range of people who engages with what we do and they have a certain curiosity and questions to us about what we are doing. In that sense I would say, we do have a public that is scattered in many parts of the world, quite densely in Delhi and like when we had a show in Kolkata we realized that we had a very interesting group of people who were interested in having conversations with us.

SG: Your work besides giving a visual stimulus also serves the purpose of intellectual stimulus among the audiences. Please discuss.

JB: See, for instance, in a lie detector test what do they check is the effect of thoughts on emotions.  So, cognition and emotions are very deeply connected. The way to feel the world is also the way to think the world. Similarly the way to think the world is also the way to feel the world. For us it's very important that we keep this link between the sense of feeling or effect of the world and the sense of thinking and making intellectual queries and challenges. For instance, when somebody dies we have a great feeling of rage or anger, sorrow or sadness but after that feeling when I am making sense of that feeling and communicating it to someone else, I am drawing through many ways of associating that event with other events that have happened in other people's life which may have learnt through literature or through cinema or through curiosity or even stories. I am also trying to make sense to bring it back to other people's life. So, that process of basically coming to terms with some deep sense that I have gathered about the world through others is interpretative and has many intellectual journeys which we like to share with the public.

So, cognition and emotions are very deeply connected. The way to feel the world is also the way to think the world. Similarly the way to think the world is also the way to feel the world. For us it's very important that we keep this link between the sense of feeling or effect of the world and the sense of thinking and making intellectual queries and challenges. For instance, when somebody dies we have a great feeling of rage or anger, sorrow or sadness but after that feeling when I am making sense of that feeling and communicating it to someone else, I am drawing through many ways of associating that event with other events that have happened in other people's life which may have learnt through literature or through cinema or through curiosity or even stories. I am also trying to make sense to bring it back to other people's life. So, that process of basically coming to terms with some deep sense that I have gathered about the world through others is interpretative and has many intellectual journeys which we like to share with the public.

SG: Please elaborate upon the themes of darkness, light, navigation and memory as conceived in the project Unusually Adrift From the Shoreline.

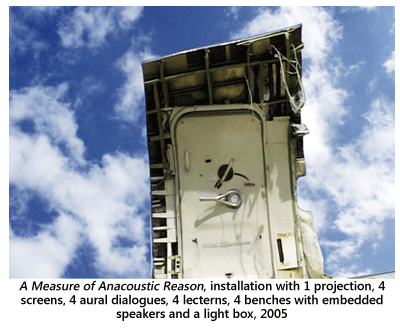

Shuddhabrata Sengupta: Basically that work was played in a cinema house. It takes both a lighthouse to be a kind of light machine and cinema house to be a light machine and cinema to be a light machine. Both the cinema as well as the lighthouse works on the principle of the intermittent relationship between light and darkness. The projector had to run 24 frames per second which means 24 times in a second there is much darkness as well as light while we are seeing the image because the light actually flickers. If there is no darkness, the lighthouse can do nothing. The question of finding one's way in the darkness presumes that there is a relation between darkness and light which is how we find our way. I give you a very simple example, when you are driving down a road at night the way you navigate that road is different from the way you navigate that road in the day time. I often travel to the airport at very late at night and I know the way. The same way I get confused in the day light. Technically I should be able to see everything, it's clearer but because I have tuned my senses to finding my way in darkness, I get confused when I am in day time on that stretch of road. In a sense the relation between light and darkness, what is visible and what is invisible, is how we make meaning as we travel through this. If we are confronted with the invisible, we make meaning out of the invisible or the barely visible or the barely legible.

SG: One of the recurrent themes in your work is Time and Location. Would you please speak on this in the context of The Wherehouse, the project you did in Brussels?

SS: The Wherehouse is based on a collection of two kinds of abandonment. There are abandoned objects and there are memories of abandoned objects. So, you have the figure of so called illegal aliens in Europe who only remember their world of objects that can be a tea cup or a tooth brush and they have memories attached to that. On the other hand, there are things that are discarded in Europe itself. The installation thus brings together the experience of abandonment with the memory of abandonment. The experience of abandonment is something to do with the location where the work is sited which is in Europe today in the 21st century. The memory of abandonment has to do with the world that has been left behind by those who have come to Europe. In this sense things are left behind either in space or in time. Thus, both location and sensuality are the two canvases against which the abandoned figure or this object is cased in this work.

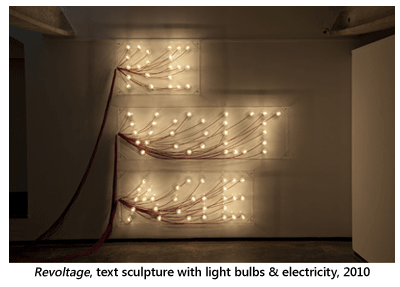

SG: One of the interesting features of your textual installations is duality. I would like to know more about it.

MN: I believe, whether you are addressing Physics, or Biology and Medicine or Philosophy  or any art, the more you know of the world and what people are capable of more the beauty they can produce. All these fields are important to understand the world better. So, writing around the idea about how to be in the world, whether it is in spiritual context or in a religious context or in some mythic context like Mahabharata or Ramayana that we often referred to in our work, is interesting for us. We are inspired a lot by the idea of Jataka tales, like in Unfamiliar Tales there is a pair of image-text that tells very short stories of two Jakata tales of equal length. If I remember correctly, at that moment someone invited us to think about Tibet and the politics of what was going over there. At the same time we were also thinking about Kashmir, as the problem of occupation whether it is Kashmir or Tibet is not different. We were also thinking about the relationship between what it means to experience that you have to live through the duration of time in which as a member of society you have to wait and hope to watch the change but do not know when it will come and it if it will come how painfully it will come. So the idea of mutation of the self in which you experience something so that you can understand your last condition better was very inspiring for us. The frozen bicycles in the work indicate all this. It is all about waiting for the thaw, waiting for the ice to melt and in a sense waiting for the politics to change if we want.

or any art, the more you know of the world and what people are capable of more the beauty they can produce. All these fields are important to understand the world better. So, writing around the idea about how to be in the world, whether it is in spiritual context or in a religious context or in some mythic context like Mahabharata or Ramayana that we often referred to in our work, is interesting for us. We are inspired a lot by the idea of Jataka tales, like in Unfamiliar Tales there is a pair of image-text that tells very short stories of two Jakata tales of equal length. If I remember correctly, at that moment someone invited us to think about Tibet and the politics of what was going over there. At the same time we were also thinking about Kashmir, as the problem of occupation whether it is Kashmir or Tibet is not different. We were also thinking about the relationship between what it means to experience that you have to live through the duration of time in which as a member of society you have to wait and hope to watch the change but do not know when it will come and it if it will come how painfully it will come. So the idea of mutation of the self in which you experience something so that you can understand your last condition better was very inspiring for us. The frozen bicycles in the work indicate all this. It is all about waiting for the thaw, waiting for the ice to melt and in a sense waiting for the politics to change if we want.

SG: What new spaces and concepts you are going to explore next? What are your new projects? I am looking forward to receive yet another interesting story from these wandering Dervishes.

MN:There are number of people we are working with right now. We have been invited to Baltic Sea off the west coast of Finland. They are inviting some artists from across the world to be there in the island of Baltic Sea to make something about that island or to respond to that landscape. We had gone there, talked about it and what we have decided is to make a piece of five word phrase which is going to be very large, may be the size of each letter is six foot tall and a silver mirror floating in the Baltic Sea and the text is saying “more salt than your tears”. This, of course, is in the context which talks about the relation between the human body and the sea that has no salt in it (due to the difference in salinity the upper surface has very little salt). This is about something which is very personal in connection to something quite physical, something which is the part of the landscape, and something which you can connect to in many ways. We are working on it right now and it will open in June in Finland. We are also working on a film piece, a video which is about how one can re-imagine the night not as a time of making yourself strong against the next day's labour. The whole idea is that when you go to sleep at night you prepare yourself for tomorrow's work. This is one way of looking at night. The other way is what the capitalism or the hedonism has given us which denies that tomorrow will come. But what we are thinking is how one can imagine the night which is neither denying nor preparing but about being in the night so that you can get something more than either of these things.

Image Courtesy: Norbert Thigulety | Raqs Media Collective | Radhusteateret, Stavanger | Project 88 Gallery