- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Sheela Gowda

- The DIY Artist with a Mission

- Discovering Novel Horizons

- A Conversation with Raqs Media Collective

- Manjunath Kamath

- Jitish Kallat- the Alchemist

- The Artist and the Dangers of the Everyday: Medium, Perception and Meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work

- An Attitude for the Indian New Media

- Weave a Dream-Theme Over Air or a Medium like Ether

- Installation in Perspective: Two Outdoor Projects

- Towards The Future: New Media Practice at Kala Bhavana

- Workshop @ Facebook

- Desire Machine: Creating Their Own Moments…

- Typography: The Art of Playing with Words

- Legend of a Maverick

- Dunhill-Namiki

- The Period of Transition: William and Mary Style

- The Beauty of Stone

- Nero's Guests: Voicing Protest Against Peasant's Suicides

- Patrons and Artists

- The Dragon Masters

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Winds of Change

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- In the News

- Previews

- Ascending Energy, Merging Forms: Works by Satish Gujral

- Re-visiting the Root

- The Presence of Past a New Media Workshop

- Taue Project

ART news & views

The Artist and the Dangers of the Everyday: Medium, Perception and Meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work

Volume: 3 Issue No: 15 Month: 4 Year: 2011

by Claudio Maffioletti

Gupta's skepticism towards definitions and their unbearable weight did not surprise me. Her uneasiness in front of the uncompromisingly synthetic and limiting character of categories was easily expected. For expressions such as “new media art”, “net art”, and the like, whilst providing a ready-made framework of meaning, dismiss some of the most crucial factors to understanding artistic expression: the perceptions giving birth to its inception, the processes through which it evolves, and the interpretations shaping its meaning.

In fact, to the artist's eyes, hands and thoughts, there's little difference between red liquid and a microphone,  a roll of tape and a sentence. “All of them are a medium, embodying in it a possibility in terms of meaning, function or value which I try to explore” she concedes.

a roll of tape and a sentence. “All of them are a medium, embodying in it a possibility in terms of meaning, function or value which I try to explore” she concedes.

The attention Shilpa Gupta gives to the media she happens to work with is evident throughout her work. To unfold the red thread connecting the variety and diversity of her works, to recuperate the narrative lying beneath her trajectory, a brief immersion into some of Shilpa's most significant works proves to be necessary.

The projects which earned the artist's first reputation were embedded with a radical, provocative and repulsive critique of the culture of mass consumption, religious control and gender prejudices: in Untitled, 1997 (prove that you care) the artist offered memories for sale; in Untitled, 2001 she prepared an instructions manual requesting users to stain the provided cloth with menstrual blood and to return it to her; in Your Kidney Supermarket (2003) a sales network is created, and a street-shop is opened, to sell cellophane-packaged anthropomorphic items.

In Untitled, 2001 Gupta takes on the role of the pilgrim, visiting holy places to get her blank canvas blessed. At once, the work is an exploration of the mechanisms of faith and belief and a questioning of the role of the artist in “manifesting collective religious aspirations of society”. This interest in the role of artist as agent of social consciousness is then translated into the World Wide Web environment and its wider political implications. Her websites are platforms unveiling the abjections inherent to our interconnected world, where the mechanism of online booking and purchasing becomes the metaphor for the compulsion to consume. In diamonds and you (1998), before signing-out for payment, the user is addressed with a few questions: through which route to smuggle the diamond in India? What is the age of the stone-cutters? How much is their monthly pay? Sentiment Express (2001) was a purple-satin-decorated boot inside, a seat, a pc and a monitor were ready for comers to write love letters. Once emailed to Shilpa and her colleagues in Mumbai, the same were written on paper and couriered to the final recipient. Blessed Bandwidth (2003) used to be a website providing online blessings along with paraphernalia, rituals and impositions typical of any religion. The anxious path towards holiness, paved with alerts and pop-ups.

Whilst denouncing the asymmetries and inequities of a globalised world, in her subsequent work Shilpa further develops a discourse more focused on the significance originated by the media itself. Within this framework, the notions of accessibility and interactivity come to the forefront. Blame (2002-04) originated in Aar Paar, a cross border public art project, and its first form was a series of posters distributed on the streets of Karachi and Mumbai. After this, a set of plastic bottles containing simulated blood with the label 'blaming you makes me feel so good, so I blame you for what you cannot control your religion, your nationality were displayed inside a gallery, neatly arranged on the shelves of a glass cabinet and immersed in red light, as if sold in a psychedelic pharmacy. As in all the medical products, the ironic instructions prove to be a Don-Quixote's adventure, as they invite the patient to “squeeze small quantity on dry surface. Neatly separate into four equal sections (can be unequal too). Tell sections apart according to race and religion”.

Within this framework, the notions of accessibility and interactivity come to the forefront. Blame (2002-04) originated in Aar Paar, a cross border public art project, and its first form was a series of posters distributed on the streets of Karachi and Mumbai. After this, a set of plastic bottles containing simulated blood with the label 'blaming you makes me feel so good, so I blame you for what you cannot control your religion, your nationality were displayed inside a gallery, neatly arranged on the shelves of a glass cabinet and immersed in red light, as if sold in a psychedelic pharmacy. As in all the medical products, the ironic instructions prove to be a Don-Quixote's adventure, as they invite the patient to “squeeze small quantity on dry surface. Neatly separate into four equal sections (can be unequal too). Tell sections apart according to race and religion”.

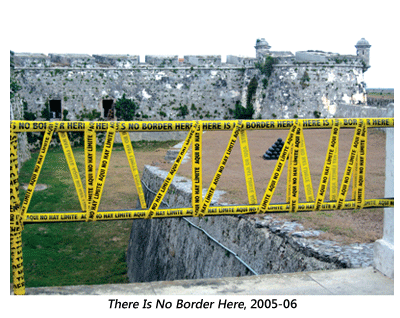

The artist broaches similar concerns in There is no border here (2005-06) and There is no explosive in this (2007): a mass-produced tape distributed to various people and in various places around the world; suitcases, bags and backpacks with the statement printed on it. Here the stress on the anxieties deriving from a utopian world without borders, violence or terrorism is further enhanced by the reverse effect the two statements enact. Unrolling the tape to delimit areas does create a border, as carrying a suitcase on the streets saying there is nothing to worry about, instills the doubt that yes, we all have to be worried about something. In addition, the notion of authorship is extended and, to a certain extent, obliterated, as the tapes and the suitcases keep performing their meaning even when deprived of their author or of their original context. Eventually, these works appear to be more mature reflections on the nature of language and its relationship with both truth¹ and memory.

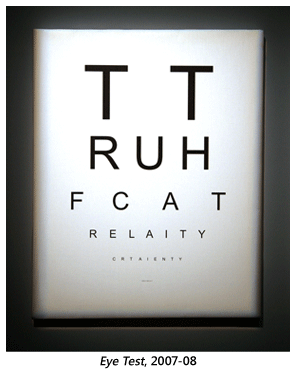

These elements will be elaborated in a more accomplished way later on with Eye Test (2008) and Memory I, II, III (2007-08), where the associations between vision, language, thought, memory, understanding and unconsciousness is achieved through an array of strikingly simple and immediate tools and devices: the eye-test sheet we normally see at doctors clinics, a concrete wall, a pile of white papers. Once again, the insistence on the used medium, the exploration of their use value and the interpretation of their function in the quotidian recur. The same happens with microphones, the object that ubiquitously populates the political life of India. Tryst with Destiny (2007-08) is a lonesome microphone reciting - with the artist's passionate, mournful, moaning voice - the speech Jawaharlal Nehru gave in 1947, on the wake of Indian democracy, with the never completely fulfilled promise of freedom,  justice and equality. Singing Cloud (2008-09) is a gargantuan and amorphous lump made of thousands of microphones singing and whispering with different voices: I want to fly | High above in the sky | Don't push me away | We shall all fly | High above in the sky | I want to fly high above | In your sky | Can you let it be | Only your power | And not your greed | A part of me will die | By your side | Taking you with me | High high above | in the sky | While you sleep I shall wake up and fly.

justice and equality. Singing Cloud (2008-09) is a gargantuan and amorphous lump made of thousands of microphones singing and whispering with different voices: I want to fly | High above in the sky | Don't push me away | We shall all fly | High above in the sky | I want to fly high above | In your sky | Can you let it be | Only your power | And not your greed | A part of me will die | By your side | Taking you with me | High high above | in the sky | While you sleep I shall wake up and fly.

In both cases, the apprehension on the physical impossibility of pacific co-existence and mutual understanding among human beings is transposed to a superior, more problematic level of significance, exactly by investigating the medium's functioning. The sense of fear, the feeling of disquiet seeping out of the installation has its origin in the fact that the tool's role of propagator and disseminator of audio messages is here disrupted, as it ceases to execute its tasks if no listener or audience is present. Thus, at the end of this condensed path, a few recurring elements seem to concur in the construction of meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work. The medium turns into a repository of significance, as the artist, by investigating its uses, the symbolic values attached to it or, as McLuhan would put it, the “massage”² it performs on our senses, anchors the art object to the reality of life. This, in turn, allows the work to function on diverse levels and to be read in multiple ways. Thus, it becomes at times so open that it would not accomplish its full significance without the intervention or absence of viewers, the “participants by default” in Gupta's imagery.³ Therefore, interaction and nomadism are combined strategies allowing her work to be continuously interpreted and experienced, acquiring new meanings depending on the individual sensibilities of participants. Perceptions are in fact the artist's deeper inspiration, the trigger through which she is able to come to terms with her own and everybody's life, to give a shape to the quotidian absurdities and dangers hiding in our everyday acts. “If a definition has to be” she admits “call me an everyday artist”.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

¹ How to do Things with Words: The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Ed. J.

O. Urmson, Oxford: Clarendon, 1962.

² M. McLuhan, Q. Fiore, The Medium is the Massage An Inventory of Effects, 1967

³ U. Eco, Opera Aperta, 1962 rev 1976.

Image Courtesy: The Artist