- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Sheela Gowda

- The DIY Artist with a Mission

- Discovering Novel Horizons

- A Conversation with Raqs Media Collective

- Manjunath Kamath

- Jitish Kallat- the Alchemist

- The Artist and the Dangers of the Everyday: Medium, Perception and Meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work

- An Attitude for the Indian New Media

- Weave a Dream-Theme Over Air or a Medium like Ether

- Installation in Perspective: Two Outdoor Projects

- Towards The Future: New Media Practice at Kala Bhavana

- Workshop @ Facebook

- Desire Machine: Creating Their Own Moments…

- Typography: The Art of Playing with Words

- Legend of a Maverick

- Dunhill-Namiki

- The Period of Transition: William and Mary Style

- The Beauty of Stone

- Nero's Guests: Voicing Protest Against Peasant's Suicides

- Patrons and Artists

- The Dragon Masters

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Winds of Change

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- In the News

- Previews

- Ascending Energy, Merging Forms: Works by Satish Gujral

- Re-visiting the Root

- The Presence of Past a New Media Workshop

- Taue Project

ART news & views

A Conversation with Sheela Gowda

Volume: 3 Issue No: 15 Month: 4 Year: 2011

Creative Impulse

by Nalini S Malaviya

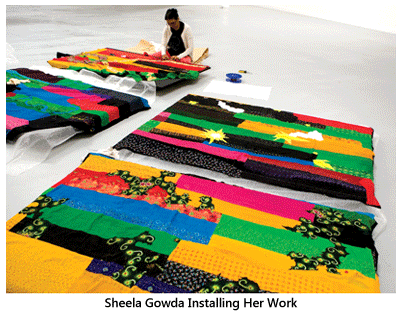

Nalini S Malaviya converses with the Bangalore based artist Sheela Gowda who recently presented her first solo exhibition in the UK at Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), Rivington Place. Gowda is known for her large scale sculptural installations, which transform ordinary materials that have symbolic associations into conceptual works with references to gender, politics and society.

Nalini S Malaviya converses with the Bangalore based artist Sheela Gowda who recently presented her first solo exhibition in the UK at Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts), Rivington Place. Gowda is known for her large scale sculptural installations, which transform ordinary materials that have symbolic associations into conceptual works with references to gender, politics and society.

NSM: Your first solo exhibition in UK Therein & Besides was on at Iniva, Rivington Place, London since January this year and concluded recently...

SG: I was invited by Grant Watson, who has joined Iniva as a curator. I have worked with Grant since the year 2000 in several of his exhibitions. For instance, recently I participated in the exhibition Textiles Art and the Social Fabric. Prior to that there was an exhibition Santhal Family: Positions Around an Indian Sculpture, which involved many Indian artists.

NSM: You studied at Ken School and then went on to study at Santiniketan before doing an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art, London followed by a stint at the Cite International des Arts, Paris. This issue of ART news and views focuses on new media and installation art. In that context, apart from these multiple cultural and international influences, what brought about this transformation from painting to sculptural installations?

SG: I do not think what happens outside by itself can make a transformation within you; it has to come from certain needs within you. I have talked extensively about what led to the transformation within my work in the early nineties. It is not easy to be precise about why something happened. There were a number of factors involved. It was to do with certain artistic concerns, certain political situations, one's response and questions about them as an artist, as an individual, as a citizen, questions regarding issues external to one's own art practice and the language one is using in relation to that - the why's and what's of it. These are all very broad questions but when you consider them seriously, they become intimate issues, something that you thrash out within your mind, within the four walls of your studio while testing it out against outside factors also. Then there are moments when you also think about how other artists have dealt with issues around them, although their solutions may not necessarily solve your problem.

NSM: Did you at any point feel that there was any limitation to restricting yourself to just pigments and canvas? On the other hand, how difficult is it for a painter to start relating/responding and working with different mediums, materials and spaces?

SG: Painting is not just about canvas and pigments, it is about the materiality of the paint, about touch, it is about space, about pictorial space, the space between you and the canvas, between you and the viewer, there are many dimensions to it. If you look at it this way, it seems it is not such a drastic change after all, to pick up another material and work with it. Formally within my painting, I had investigated an abstraction of the ground that the characters or the elements inhabited. It was my main preoccupation when I was painting. I was always reworking the elements in them, investigating the idea of the relationship of the figure, the form, of the space within them, their borders to the space around them, to the tension of being, becoming. This allowed me to move into the kind of abstraction, firstly in the cowdung works that followed my painting period and then on to the more sculptural installation works. The very ground in a painting has become the space of a room. But you are adding several more formal and conceptual issues on your plate to deal with, issues of space and material for instance. There is the danger of becoming very literal unless one is able to transform these onto other levels of perception.

The painted image is not the photograph of a person and a photograph is different from the person as well. It is the same with any material that you choose to work with, because it will have its own resistance, it will have its own will, it will have its own history but at the same time it can be quite passive and allow you to do things with it. The challenge then is what do you, the artist, do with it? How do you use it or misuse it, respect or disrespect its character? In my case, I have always wanted to let the material speak for itself and not supersede it completely, yet it is the material that I have chosen amongst thousands of other materials.

The painted image is not the photograph of a person and a photograph is different from the person as well. It is the same with any material that you choose to work with, because it will have its own resistance, it will have its own will, it will have its own history but at the same time it can be quite passive and allow you to do things with it. The challenge then is what do you, the artist, do with it? How do you use it or misuse it, respect or disrespect its character? In my case, I have always wanted to let the material speak for itself and not supersede it completely, yet it is the material that I have chosen amongst thousands of other materials.

There is a reason, a purpose and something that I want to say to it, with it, which is why I have come to using varied but specific materials for a long time and continue to do so. You can take a material and break it up or cut it up, make it seem like something else altogether, give it another identity, so much so that the material itself does not matter and what appears finally becomes its new identity. I am not interested in using material this way. I've always been interested in the material itself and what it represents.

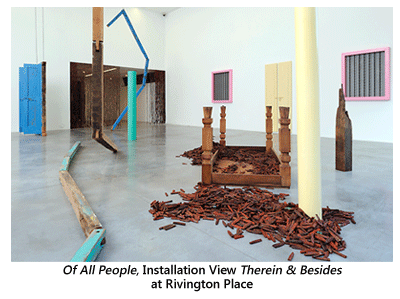

NSM: Coming back to your exhibition at Iniva, could you share a little bit of information about the new work, Of All People (2011), which is made up of numerous wooden chips, that form part of a composition of larger frames and doors that are multi-coloured.

SG: These innumerable pieces of wood are just one element in the work. The work comprises of door frames, windows (real ones), which were sourced and reworked. Some were dismantled, and transformed into linear elements. A table is placed upside done, its legs in the air, creating a space in between, upon which are piled thousands of these wood pieces. Beside the table lies a wooden elephant with its four legs up in the air as well. Pedestals are important elements too in the installation. The wooden chips are actually human figures which you perceive only on close scrutiny. The finger sized wood pieces have three marks imprinted on one end to represent a human face giving each a unique facial expression. Other rudimentary marks delineate the rest of the body. This aspect of a material which lies on the edge of being a material, in this case a mere piece of wood but in fact is a human figure interested me. Of All People is a work that questions its own identity suspended between abstraction and representation.

The work addresses time, your own presence the sense of being oversized and gigantic while looking down on these little people or turning into normal human proportions standing in front of a real door or a window. While standing in front of a door or a window, with the volume of space all around it, the inside and outside is not clearly determined and becomes interchangeable.

Abstraction is a means and an end. On the surface, the work seems to consist of brightly coloured and fragmented wooden elements, but they are in fact very specific in what they have been in daily use. One can read it from this specificity, or as colourful forms in space, or as signs or signifiers. For example when one realizes that the innumerable small pieces of wood are not just bits of wood but are human figures it adds a complexity to the way we see things and give meaning to it.

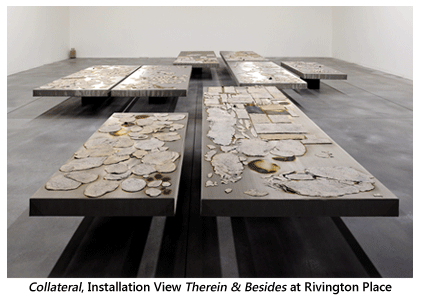

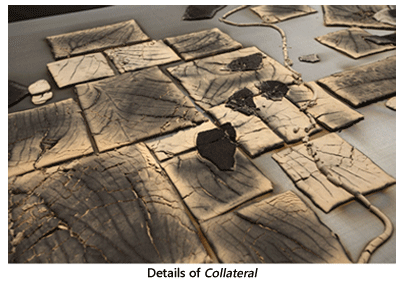

NSM: Collateral (2007) is also a part of this exhibition and suggestive of a landscape ravaged by war. Could you explain a little bit about it too?

SG: Collateral was first shown at Documenta 12, but it was not the first time I have used ash as a material (remains of burnt incense). Ash here is just one part of the work. The ash rests on differently proportioned grey 'beds' made of stretched metal mesh on frames, which are positioned 30 cm above the ground giving it a floating quality. This gives the work a constructivist presence. The steel mesh allows air to flow beneath the incense for it to burn. It is a practical need which I have made an essential component in the reading of the work. For me, this aspect of combining practical issues to the conceptual is very important. Conventional sculpture tends to subscribe a passive role to the pedestal that it is placed upon. But for me the 'pedestal' is an integral part of the work. A pointing finger is not a tool to look elsewhere but in itself of interest.

The steel mesh allows air to flow beneath the incense for it to burn. It is a practical need which I have made an essential component in the reading of the work. For me, this aspect of combining practical issues to the conceptual is very important. Conventional sculpture tends to subscribe a passive role to the pedestal that it is placed upon. But for me the 'pedestal' is an integral part of the work. A pointing finger is not a tool to look elsewhere but in itself of interest.

NSM: It creates multiple levels of interaction...

SG: If you are looking at a small bronze sculpture placed on a pedestal, perhaps one thing that could be manipulated is the level at which it is to be viewed. You can either be looking down at it, see it at eye level or look up to it. Depending on where the pedestal is placed you can go around it or view it from one side only. The sculpture in all these positions is the supreme artwork. The pedestal here is a mere support or a means of framing the work. But, if we challenge this convention, if we make the pedestal 'visible' if the relationship to the object on it becomes an artistic concern, a conceptual issue, then you are pointing to a self awareness of the viewer in a very different way. If the pedestal has nothing to say and you are giving it too much importance then that is a problem too.

NSM: Is it difficult for you to source materials (tar drums, kumkum, paper, printed textiles, thread etc)?

SG: It is not difficult in the sense that these are not rare items. One of the reasons I choose them is because they are common and everyday objects. But when it comes to finding those that you can work with, it can be difficult to buy them in large numbers because the people who you source it from resist you in a way. You do not fit into their idea of a conventional client, with conventional usage of what you are buying or they have certain preconceptions about what they think you want. Their simple question 'what do you want it for' is the hardest to answer (for myself as well when I am at that stage of art making). So, it is always a social encounter of sorts. Most often the process of sourcing one material leads to and introduces me to the possibility of other works.

NSM: So that itself must be a fun and exciting process?

SG: Yes, but also very tedious. I do not delegate this job to someone else because it is not a simple task. Somehow, it has become an inevitable part of my art making and I do seem to have a knack for observing and locating things. I am very particular about what my needs are and that particularity usually means negotiations, making enquiries from one shop to another, reading between the lines of what people say and keeping my eyes open, not only for what I am intending to buy but also for all that is full of potential and meaning as artist material. So, there's always a fascination with these places. Of course not all that you encounter is of interest to you. You choose what touches you, and what touches you is what preoccupies you, and what preoccupies you is what you observe around the world and what you want to respond to!

NSM: Does it happen that when you go out looking for materials, you encounter new materials or meet people who may influence the direction that you were going initially?

SG: I go looking for very specific materials,  because I know by that stage, what I want to experiment with, to bring into my studio, to begin the process of creation in physical terms. Nevertheless, in the process of creating one work, the possibilities, conceptual process of another could begin. 3 or 4 very different works have come out of one particular shop alone.

because I know by that stage, what I want to experiment with, to bring into my studio, to begin the process of creation in physical terms. Nevertheless, in the process of creating one work, the possibilities, conceptual process of another could begin. 3 or 4 very different works have come out of one particular shop alone.

NSM: Most of your works are created through an intense and intricate process for instance, And Tell Him Of My Pain. On a personal level, how important do you feel is the 'process' in the production of art?

SG: When the making of an artwork is not about the execution of the first idea that comes to your head, but a sieving or filtering of many, then the process definitely becomes an important part of it. It is not that I set out to create a lot of work for myself but it becomes necessary, because what I want to say should not weigh like concrete, but be elusive. It becomes necessary for the work to go through a process to achieve that lightness. Perhaps, elusive may sound like it is about nothing, vague, but for me a work should resist the common and simplistic interpretation of many viewers and art writers who want to say 'this work is about this and that'.

NSM: Your works are quite complex, a lot of layers are involved and appear to be abstract, so that when a person enters that space there is an interplay of meanings that can be generated, do you find that for an ordinary viewer when he is looking at your work, he is able to read it in a way that you had envisaged?

SG: Firstly my work is 'readable' within itself at one level. For the viewer to have their senses alert to the everyday elements in their life is not too much to expect. For instance, while viewing a door the process of reading starts with a recognition of what it is, its function in daily life and by further reading, a metaphor. A door frame which in a dismantled state becomes a linear element in space creates a disruption of this view, a rocking of certainty. When a viewer concludes prematurely or wants ready explanations in easy sentences, there is no receptivity left. You need to have imagination. If you cannot see anything in a door to begin with what can I do about it?

NSM: What are the kind of issues which act as a stimulus for you in creating an artwork?

SG: It depends. The starting of each work can be quite different! And, I don't believe that you can be a good artist by having a list of things that you want to say. I think this is a recipe to make bad art. Not because there is something wrong in being specific, but I think art is not about giving opinions or stating these in black and white terms. Art should be something beyond that. There's nothing wrong in having an opinion but it is not art. I can have opinions about topical issues, the civic administration or the government but airing those opinions does not make it art. It is important to have an opinion and to act on it.  In fact I have strong views on many issues. This is what feeds my thought process. It feeds into the way I engage with the world, what I observe around me, what information I find interesting in a newspaper, which is not just about being a passive reader. I would love to write a column in a newspaper once in a while.

In fact I have strong views on many issues. This is what feeds my thought process. It feeds into the way I engage with the world, what I observe around me, what information I find interesting in a newspaper, which is not just about being a passive reader. I would love to write a column in a newspaper once in a while.

NSM: Today many young artists are drawn to new media and conceptual art, in your opinion is it a mere rejection of the conventional or is there a deeper emotional and intellectual notion behind it, an intuitive response to the changing times.

SG: A critical engagement is necessary whether you are painting or using new media. That engagement can come about only when you observe the world, by how you process what you see and read, and how you deal with your emotions. There are artists who are honest to themselves, they are not trying to be someone else, or the notion of something they have not grasped fully. Their works, even if it looks amateur, has potential to evolve in the future and be of interest. This has nothing to do with the medium. The only danger with certain new media is that you can appear to be exciting. It is a trap then for both the viewer and the artist, but a bigger one for the artist I think. Because the interest the artist gets can be misinterpreted. It takes a long time or sometimes forever to retract and find the right way. It is important to get feedback, but the artist needs to be the first and last critic towards his/her own work.

Images Courtesy: Institute of International Visual Arts