- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Sheela Gowda

- The DIY Artist with a Mission

- Discovering Novel Horizons

- A Conversation with Raqs Media Collective

- Manjunath Kamath

- Jitish Kallat- the Alchemist

- The Artist and the Dangers of the Everyday: Medium, Perception and Meaning in Shilpa Gupta's work

- An Attitude for the Indian New Media

- Weave a Dream-Theme Over Air or a Medium like Ether

- Installation in Perspective: Two Outdoor Projects

- Towards The Future: New Media Practice at Kala Bhavana

- Workshop @ Facebook

- Desire Machine: Creating Their Own Moments…

- Typography: The Art of Playing with Words

- Legend of a Maverick

- Dunhill-Namiki

- The Period of Transition: William and Mary Style

- The Beauty of Stone

- Nero's Guests: Voicing Protest Against Peasant's Suicides

- Patrons and Artists

- The Dragon Masters

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Chennai

- Art Events Kolkata

- Winds of Change

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Musings from Chennai

- In the News

- Previews

- Ascending Energy, Merging Forms: Works by Satish Gujral

- Re-visiting the Root

- The Presence of Past a New Media Workshop

- Taue Project

ART news & views

Discovering Novel Horizons

Volume: 3 Issue No: 15 Month: 4 Year: 2011

A Conversation between Pankaja JK and Kausik Mukhopadhyay

Strolling down the memory lane of nature clad Santiniketan and reaching the present city streets, Kausik Mukhopadhyay unfolds his memories and experimentation with art. His interest in utilizing different and new media for expression makes his art an attractive and interesting work. Let us share his experience:

PK: Going down through memory lane to your days of art school at Santiniketan and the present mazy place, Mumbai that you live and work in, do you find a vast difference between the two.

KM: I grew up in Kolkata, around the Ballygunge and Tallygunge area. I went to Rabindra Bharati University at Jorasanko and my adda was at Kalighat. Our teacher from Patha Bhavan, Dipankar da (Dipankar Sarkar) used to live there. Dipankar da and Kanchan da (Kanchan Dasgupta), who is an artist, formed a theater group with us. We were seventeen or eighteen years at that time. It gave us a sense of belonging and was a great learning experience. I loved to spend time moving around Chitpur road or in the maze of Barabazar and in the industrial area of Howrah where my friends Debnath and Tamal (Debnath Bose and Tamal Mitra) stayed.

I went to Santiniketan to do my Masters for two years. My relationship with Santiniketan though has a longer history. My grandfather's home was there and his brother had lived there since 1910. My grandmother (maternal) and her family also lived there in the 1930-40s. I was familiar with Santiniketan but never stayed there except during vacations. When I joined as a Master's student I found the place to be rather suffocating. I stayed in the hostel, though quite a few of my relatives stayed within a kilometer radius. I imagined it would give me freedom. Like all small towns, Santiniketan did not give me any anonymity. I hated it. I like the big city with the possibility of the invisible cloak of the crowd.

So when I came to Mumbai it was not a “mazy place” to me but a place where I felt at home.

Later when I joined Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies at Juhu, 1996, the college was only four years old. There was a bunch of young faculty with the excitement of forming new methods of teaching. It was a new sense of belonging.

PK: What is the effect of Santiniketan and mazy Mumbai on your creative thinking and practical application of it in your work?

KM: At Rabindra Bharati University Partha da (Partha Pratim Deb) was a great teacher. When we were in our third year Pinaki da (Pinaki Barua) joined. He changed everything. His enthusiasm and meticulous teaching did away with all the things the place lacked. Darmo da (Darmonarayan Dasgupta) joined too.  We gathered around them. We had put a small stove in the studio and used it to make tea and all of them would come to our studio. Those addas were better than any class. Som da (Somsankar Roy) was an ex-student and he too joined us at that time. He was our friend and really held our hand in times of difficulty.

We gathered around them. We had put a small stove in the studio and used it to make tea and all of them would come to our studio. Those addas were better than any class. Som da (Somsankar Roy) was an ex-student and he too joined us at that time. He was our friend and really held our hand in times of difficulty.

At Kala Bhavana the studio was more than anything anyone can want. Sanat da (Sanat Kar) and Lalu da (Laluprasad Shaw) were very helpful. Nirmal da (Nirmolendu Das) made me work and guided my dissertation. Most of all, having Mani da (KG Subramanian) on campus was a boon. It was Shiv da (Shiva Kumar) I feel most indebted to. I'd never had an art history faculty like him. I didn't know how much I could imbibe from him; his method was very rigorous but I got interested in the subject.

Before coming to Mumbai in 1992, I was in Ahmedabad for two years. I got a fellowship from Kanoria Centre, CEPT for printmaking. It allowed me stay in Ahmedabad and use the studio at the Kanoria Centre. I was bored with printmaking and started to paint. I found that reverse painting on glass has the least technical hassle and can be cleaned easily when things don't work out. I was making images which contained images that we see every day and started cutting and pasting images from film magazines, advertisements, news paper and sometimes added small objects, like quotations, with painted images. I layered up the glasses one behind the other with a small gap so that someone can peep into work when looking at it. Soon they became boxes with objects and paint. While at Kanoria Centre, the proximity to Architecture College, friends who were there at that time, Tushar Joag, Manisha Parekh, Owais Husain, Soumitra Ghosh, Nisha Matthew and Walter D'Souza, were the catalyst for the change.

After I joined the college my work changed a lot. The objects came out of the boxes and became bigger and impermanent. I think it was the influence of the new friends around me and also the security of the job, making me independent of the fear of not being able sell the work.

PK: Does the academic knowledge really help the artist in creation of his work or is it based on practical experiences?

KM: I cannot speak for others but to me both have helped. If it is practice versus theory, I would give a more weightage to the latter. Though in many of art colleges it is still proudly announced that the 'power of the wrist' is ultimate, the kind of work a dead brain produces is evident in a large number of shows around the city.

PK: Tell us something about your recent work.

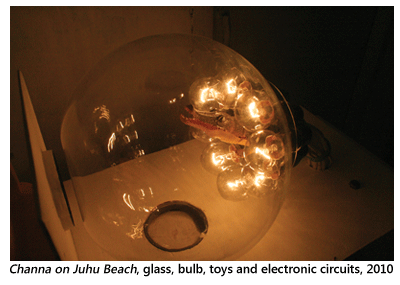

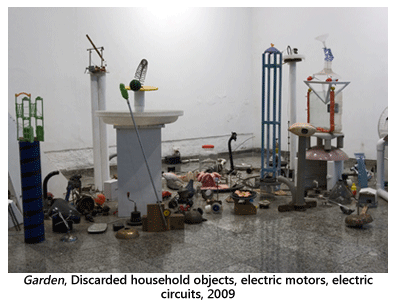

KM: Most of my works consist of discarded household objects. I use a lot of electrical devices to make them move, use circuits, electric lights. My friends give me all the junk and that way my collection grows. I don't buy them. Exchange of money makes them not so discarded. Recently I noticed that I have collected a lot of electronic appliances like DVD players, telephones, mobiles, digital cameras etc. that were all discarded to make place for new ones. This is a new phenomenon. No more repairwalas no more reuse. I was asking a kabadiwala what he does with the pile of DVD players he has. He just breaks them and sells the metal. I started to 'repair' my collected junk so they malfunction and started arranging them as a graveyard or museum, like they have in Bergen in Norway where an excavation site in the city has become a museum with the artifacts exposed in the layers they were found.

I use a lot of electrical devices to make them move, use circuits, electric lights. My friends give me all the junk and that way my collection grows. I don't buy them. Exchange of money makes them not so discarded. Recently I noticed that I have collected a lot of electronic appliances like DVD players, telephones, mobiles, digital cameras etc. that were all discarded to make place for new ones. This is a new phenomenon. No more repairwalas no more reuse. I was asking a kabadiwala what he does with the pile of DVD players he has. He just breaks them and sells the metal. I started to 'repair' my collected junk so they malfunction and started arranging them as a graveyard or museum, like they have in Bergen in Norway where an excavation site in the city has become a museum with the artifacts exposed in the layers they were found.

PK: Has it become 'trendy' to use new media in art field?

KM: When everybody was making only paintings and sculptures some twenty years back nobody thought it was trendy. Why so about new media? What is this new media term? How long will it be new? I think artists have become more experimental and lot of new things are happening. Some good and some might not be so good but definitely things are moving.

PK: According to you how would technologically progressed world be, after fifty years? Will humanism exist or mechanization take over the human ethics?

KM: I don't know. I hope humanism wins if we don't die of scorching heat of global warming or globalization. So far humans have won, proving all horror stories of the future wrong.

PK: How does it feel to interact with new generation? Do you find them fussy or more intelligent than earlier generations?

KM: Luckily due to my job I am with the new generation all the time. They are sharper and better informed and have a strong critical faculty. I do learn a lot from them but they have a lack of choices and faith. Or this might be a ranting of an old man.

PK: How much time do you spend to complete a single art work? Do you also work on other ideas simultaneously?

KM: It depends. I work very slowly and have an obsession of doing everything myself. So a big work might take a year sometimes. I do smaller works in between sometimes, sometime not. If the work is done very fast I don't like the feeling, so deadlines kill me.

PK: Lastly, your photographs projects you as a very friendly, co-operate personality. Can you define yourself?

KM: I am not sure whether I am friendly or co-operative. Will an opinion poll do?

Image Courtesy: The Artist