- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

The recently concluded Art Basel threw up a lot of hopes for the Art World. At the same time it threw up a lot of questions, mostly apprehensive. The top-of-the-market prices, set for most of the works that were sold, had fair participants smiling with satisfaction. At the same time, economic observers had eyebrows raised, as they struggled to make meaning of the brisk sales at the fair despite the overall economic gloom in Europe.

Commenting on the 43rd edition of the Swiss Art Fair, which ended on June 17, Wall Street Journal's Margaret Studer commented, “In the packed corridors of Art Basel …, the economic gloom of the outside world seemed far removed.” To illustrate her point of view, she quoted Urs Meile, who runs a gallery in Beijing, China, and one in Lucerne, Switzerland as saying, “The art market seems to have cut off from all the negative economic news. We are selling to collectors all over the globe.”

A look at the figures of trade at the fair will establish this beyond doubt. Artfix Daily, in its final report the day after the fair ended noted the significant sales:

“Unsurprisingly, a work by Gerhard Richter led sales at Art Basel. Richter's monumental 1986 red, blue and yellow abstract A.B. Courbet was sold by Pace Gallery of New York with a price tag rumored to be between $20 million and $25 million. Quickly sold was noted New York printmaker Philip Guston's painting Orders from 1978, for $6 million.

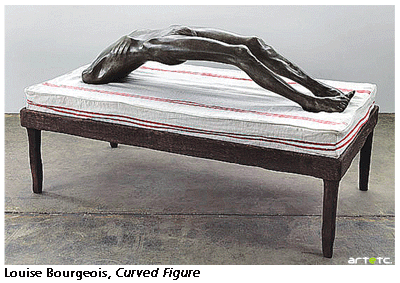

Famed French-American sculptor Louise Bourgeois' sculpture of an arched figure, created in 1993, sold for $2 million.

Famed French-American sculptor Louise Bourgeois' sculpture of an arched figure, created in 1993, sold for $2 million.

One of Paul McCarthy's recent Snow White-themed sculptures sold for $1.8 million; this particular one being a sculpture in black walnut entitled 'White Snow and Prince on Horse.' McCarthy also sold a large drawing based on this sculpture for $350,000….

Pace sold Agnes Martin's Untitled a 12-inch-square oil, ink, and wash-on-canvas circa 1961 for $1 million, as well as Claes Oldenburg's bronze and stainless steel 'Clothespin' from 1974 for $600,000, and contemporary Chinese symbolist Zhang Xiaogang's 'Face 2012 No.1' went for $450,000.

At Blum & Poe a two-part painting by Takashi Murakami, Shangri-La Blue/Shangri-La Pink, was sold for around $1.5 million. Christopher Wool's End Plate II, an alkyd-on-aluminum and steel from 1986 to a European collector for $950,000.

The Galerie St. Etienne sold a rare Max Beckmann woodcut of his most notable print, Group Portrait, Eden bar from 1923, for somewhere in the low six figures.

The Parisian gallery Lelong sold a marble sculpture by Luciano Fabro for over a million dollars, and Sprüth Magers also found a European buyer for a knitted work from 1986 by Rosemarie Trockel.

Metro Pictures sold two versions of Robert Longo's fierce Untitled (Tiger Head No. 9), both to Europeans for $295,000 apiece. Cindy Sherman's new edition, Untitled from 2010-2012, sold four out of six for $450,000 each. Austrian Franz West's giant work Gekroese made 2011 and resembling the large intestine, sold on the first day of the fair for a seven-figure sum.”

Metro Pictures sold two versions of Robert Longo's fierce Untitled (Tiger Head No. 9), both to Europeans for $295,000 apiece. Cindy Sherman's new edition, Untitled from 2010-2012, sold four out of six for $450,000 each. Austrian Franz West's giant work Gekroese made 2011 and resembling the large intestine, sold on the first day of the fair for a seven-figure sum.”

However, Rothko's Untitled from 1954, offered for around $78 million, and touted to be a star at the fair, stood unsold, so far as last reports had reached. This aspect was interpreted by Forbes' Abigail R. Esman as a result of an almost foolhardy pricing. In a tongue-in-cheek fashion, Esman wrote, “Sales reports are still coming in, with the conspicuous exception of the 1954 Rothko at Marlborough, which finally received a price tag of $78 million. And now that ArtInfo's Judd Tully has spotted the painting as the one dealer Bob Mnuchin sold in 2007 at Christie's for just shy of $27 million, it probably won't get that. Was it worth more in 2007 than $27 million? Probably. Should it be worth $78 million now? Well, that would depend on whether you think another Rothko that sold for $87 million recently was worth that much. But this is all part of the disruption and confusion of the auction game.”

This 'action game' was explained in a June 12 report by Benjamin Genocchio in Boulin Artinfo: “Partly this is because the dealers seem to have upped the ante, bringing ever bigger and more expensive artworks for sale. They are clearly competing with the auction houses but also using super-pricey works as a marketing strategy to attract media and draw collectors to the booths. Case in point: Marlborough has a Rothko for $78 million.”

Point is the Rothko never sold till the end of the fair. If that is a pointer, it only goes on to show that even for the high and mighty of the art world, a super-pricey tag may be attractive for a check-out, but not all that comfortable to get the work home and dry. At the end of the day, art therefore remains as an investment option that to a large extent takes passion and liking into consideration over pricing, no matter what galleries may think. And this was, as of now, again proved at Switzerland's Art Basel, the leading international contemporary and modern art fair, where more than 300 galleries from 36 countries showed around 2,500 artists; where the works on display ranged from abstract and figurative paintings to video and performance art with U.S. galleries having the largest presence, being 73 in attendance.

But other than these questions, a bigger question was raised by the Art Newspaper's Georgiana Adam on June 20. She argued that the excessive number of art fairs may be auguring well for large galleries but is proving to be a bane on medium and small galleries for whom participating in these fairs becomes a taxing compulsion to stay afloat as well as for artists, who are increasingly drawn towards producing art-fair-workswhich are smaller in size and mediocre in quality. Not that she convicted Art Baselit being a standard benchmark for all art fairs around the world. What she questioned was the emergence of newer fairs at new art markets in Asia and Europe, and the pressure they are creating on the first line of production especially.

Adam wrote, “Dealers are increasingly calling it “the fair marathon”: a six-week epic that started with Frieze New York (4-7 May), continued two weeks later in Hong Kong with ArtHK (17-20 May) and will reach its apogee with Art Basel, the one fair the art world really, really can't miss (14-17 June). Some brave souls, including Tim Marlow, the director of exhibitions at White Cube gallery, even slotted São Paulo's Sp-Arte (9-13 May) between New York and Hong Kong, withstanding a two-night journey by air from Brazil to Asia.

“The explosion in the number of art fairs is the most significant change in the market since the turn of the century. The numbers tell the story: in 1970, there were just three main events (Cologne, Basel and the Brussels-based Art Actuel). But the number has mushroomed in the past decade: from 68 in 2005 to 189 in 2011. This year, the Frieze brand unveils two new fairs: the New York edition last month, and the Masters fair, which de-buts alongside the London event in October (11-14).”

The reasons for the proliferation of fairs have been often cited as the need to offer a buy-it-or-you'll-lose-it situation to challenge the auction houses; a way of extending a gallery's global reach; a way of making contacts with both artists and buyers around the world; and the need to be part of today's event-driven culture.

Despite all that argument, Adam raises a valid point“This brings in its wake the need for more inventory. The art market is currently growing: based on art sold at auction, turnover last year was the highest ever, at $11.8bn, according to Artprice. But the market is supply-driven and ultimately rests on the artists' ability to produce enough material. With more fairs on the horizon, is the current model sustainable?

“The pressure that this growth has put on artists cannot be underestimated,” says Victor Gisler of Zurich's Mai 36. “They just can't produce enough.” And even if they do, the danger is that a significant portion becomes “art fair art”: pieces that are moderate in size so they fit in a booth, and are “in tune with dominant market trends”, according to the author Olav Velthuis in a recent essay, Contemporary Art and Its Commercial Markets: a Report on Current Condi-tions and Future Scenarios, writes Adam.

And then goes on to add, “As well as putting pressure on artists, the fair phenomenon is putting galleries on the spot. “It's definitely a juggling act,” says Andrew Kreps, the owner of the eponymous gallery. “I don't think anyone was dying to add yet another fair to the calendar.”

But it happens as the market matrix and pressure to remain afloat continuously pressurize an increasingly populated art-market scene, especially in Europe, America, the Middle East and the Far East. As of now, everybody identifies the problem looming round the corner, but in the haste to hurtle from one art-fair to another spread across the globe, they do not seem to have the time to focus on the solution.

Problem is, even after the problem is identified, this tendency to ignore the solution may have a tremendous backrub effect all of a sudden.

Remember the meltdown and its cause just two years back?