- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

Social Concern and Protest

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

by Rita Datta

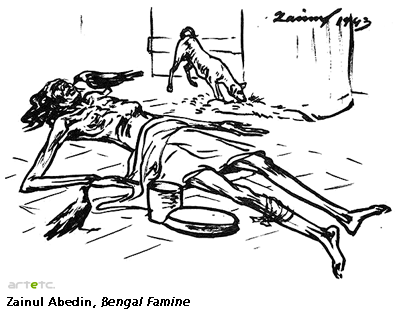

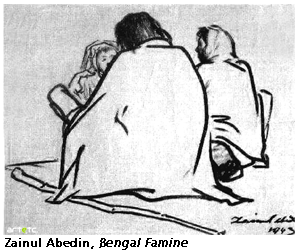

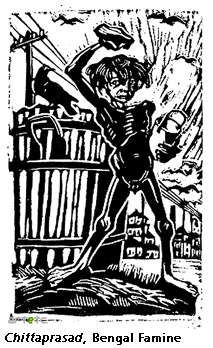

Chittaprasad, Zainul Abedin, Somenath Hore. These three names always occur together, as though they were triplets. And, in a very significant way, they were. Beginning their art around the same time, in the same region, motivated by the same thematic and stylistic concerns, they are so alike that it is difficult to tell them apart in their early work in the 1940s. For it was the 40s that shaped their sensibility, their creative identity.

In fact, the tumultuous decade of the 1940s proved critical in predicting the future of the subcontinent. Four clear trends had emerged early on. To begin with, the Quit India Movement, launched in '42, showed that the people were ready to take on British might even without the guidance of the big leaders who were all in jail. Independence now seemed inevitable and not a distant dream any more. Particularly crucial in this context was the second trend: the people's stir in the Princely States. It wouldn't be easy to unite the latter with the rest of the country, but the will of the people certainly helped.

But the third trend exposed the fissures in India's social fabric: communal and caste divides. And though the Poona Pact in 1932 brought about a compromise solution to the demand, from Dr B.R. Ambedkar, of a separate electorate for the castes called “untouchables”, the Lahore session of the Muslim League in 1940 had made it clear that nothing short of a separate nation for Muslims would satisfy it. Possibly, the only development that could have countered caste and communal conflict was a committed Left movement. And that, indeed, was there, the fourth trend. Peasants and workers were being organized by idealists of the Communist Party which, under PC Joshi, sought to rope in middle class intellectuals as well and the IPTA emerged in 1942. But neither the nationalists, nor the Communists had fully realized the reach of communal politics and that allowed the League to grow, making Partition and the bloodbath around it, India's own, shameful holocaust.

Meanwhile, the Second World War had been thrust upon the subcontinent and began devouring its resources, causing a famine in Bengal. Famines were pretty frequent in pre-British India when the land revenues extracted ranged from one-fourth to one-third of the produce and that could become even higher with additional imposts and middlemen's exploitation. But things actually became worse during Company rule because, not only did excessive revenue demands deny peasants the cushion of a marginal surplus, no relief was given even when crops failed. Besides, unlike the free kitchens that would be opened to the starving people during the medieval age, the British had absolutely no interest in providing succour to the affected. This was so even when the Crown took over the administration from the Company.

But the Famine of 1943 was different. The shortage faced was to a very great extent the result of the war and the failure of the British government to act in time. Between 7 and 10 million may have died of starvation, malnutrition and disease, even those who dragged themselves from the villages to Calcutta, dropping inert, says folklore, perhaps in front of well-stocked food shops. Yet no windows were broken, no shops looted. Their plaintive cries, “phan dao go phan dao” became the anthem of the streets. “Phan”, the starch drained after boiling rice, was all they were asking for.

These then were the circumstances that fired the zeal of the three artists. Circumstances that were, verily, inscribed in their creative conscience. They were young and idealistic and sought to expose the truth. The truth, at that point, was the socio-economic reality before their eyes. Their commitment to the cause of the people and to their ideals is written all over the sketches, paintings and prints done during those early years.

It begins, for Chittaprasad, with his name. Born in 1915 in Naihati, his surname was Bhattacharya but he refused to wear his Brahmin identity for public display. This was his own private protest against the caste system. In the two photos we see of him in vests we notice that they are both torn and that there's no sacred thread peeping from underneath. The sharp, lean face and intense gaze that characterize both portraits could have belonged to a movie star, but suggest fierce individuality. His contemporary, Zainul Abedin born in 1914 in Mymansingh - shows a milder disposition in the one old photograph available. In following their careers, you find that the former, heroic in his defiance of conventions, remained a disillusioned rebel, not at home with codes established by society. The latter, however, became a part of the Establishment in East Pakistan, as the founding principal of what was then called the Government Institute of Arts and Crafts.

It begins, for Chittaprasad, with his name. Born in 1915 in Naihati, his surname was Bhattacharya but he refused to wear his Brahmin identity for public display. This was his own private protest against the caste system. In the two photos we see of him in vests we notice that they are both torn and that there's no sacred thread peeping from underneath. The sharp, lean face and intense gaze that characterize both portraits could have belonged to a movie star, but suggest fierce individuality. His contemporary, Zainul Abedin born in 1914 in Mymansingh - shows a milder disposition in the one old photograph available. In following their careers, you find that the former, heroic in his defiance of conventions, remained a disillusioned rebel, not at home with codes established by society. The latter, however, became a part of the Establishment in East Pakistan, as the founding principal of what was then called the Government Institute of Arts and Crafts.

And what about the third artist, Somnath Hore, the Communist Party comrade and follower of Chittaprasad? Born in 1921, he was younger than the other two by some 6/7 years. Driven by the same passionate humanism, Hore had become a Communist activist early in life, and though his sympathy for the wretched of the earth remained undimmed, its ambit extended beyond millennial prescriptions to a universal vision as he grew older. Indeed, the narrower socio-economic concerns came to be distilled into a philosophic paradigm for suffering which afflicts man and beast alike. It wouldn't be inaccurate to say that he never quite came to terms with entrenched power structures. But the rebellion of his younger years had mutated into pained empathy for suffering in his prints and bronzes.

In terms of the testamental force of his imagery, the barb of satire, you have to turn to Chittaprasad first. His early works chronicle major trends from the subaltern perspective. Possibly, scorn of art business made him leave many works unsigned as they were meant for Communist propaganda. Quite a bit of his pamphlet art has, therefore, been lost to posterity. It's incredible that this talented artist was denied admission to Calcutta's Govt. School of Art and Santiniketan's Kala Bhavan. Yet it's fascinating the way messages have been articulated as stark, powerful visuals. The famine of 1943 is what brought the artists wide recognition among the people and earned them the ire of the British government, which banned and burnt Chittaprasad's Hungry Bengal where his famine pictures and reports were compiled. If the irony of fighting Hitler in the name of democracy while borrowing the Great Dictator's Fahrenheit 451 measure occurred to the British, it bothered them not. But there is much else besides that indicates Chittaprasad's awareness of socio-political issues.

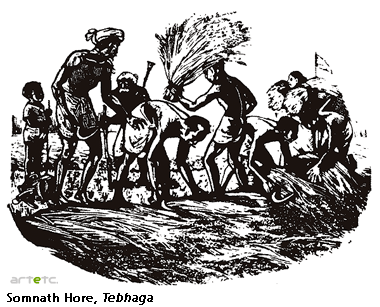

A woodcut focuses on a cinematic angle in recording a rickshaw puller lugging his car with its load: a well-fed couple. The work is as much about his sympathy for urban wage earners as an indictment of the middle class, represented by the riders, with the man frowning in irritation at the rickshaw puller. There's a bristly suggestion here: that the rich are easy to mark out as exploiters, but the middle class, behind its liberal slogans, is actually as uncaring. Another work has a peasant, face down, tied to the ground like Gulliver, while an elaborate pageant of war preparations unfolds on his prone back. Hyperbolic as this sounds - poster gists can't but be hyperbolic - the clarity of his analysis is indisputable. For it is true that the war effort in Asia was funded from the revenue paid by the peasants. Aspiration towards a pan-Asian identity, which needed to be protected from the West, is the subject of an ink drawing. The Tebhagha movement of sharecroppers in Bengal demanding two-thirds rather than half of the produce, the Naval Revolt, and communal peace stimulated this crusader, too. And it's important to note that he clearly felt that armed rebellion was the only resort of helpless victims assaulted by powerful enemies from all sides.

His sympathies did not change with Independence. Like most Communists he must have felt that “yeh azadi” was “jhuta”. So though the policy shifts and factional squabbles in the Party had already disillusioned him, his anger still simmered in an ink drawing that saw the Indian state as a many-armed monster policeman, wielding guns, handcuffs and the tricolour to suppress the grievances of the people in the year of the first general elections, 1952.

If masculine lines, fullness of stylized forms and caustic political allegories defined Chittaprasad's art, a lyrical romanticism suffused much of Abedin's work, revealing glimpses of a Santiniketan influence in his watercolours. Even in depicting the famine he seemed more reticent with fewer lines that are, however, as evocative in their power. While both the artists painted landscapes in lucid watercolours, the sketchy spontaneity of Abedin's lines is often noticeable. Nature was an inspiration, obviously, for it was his tribute to the river Brahmaputra that earned him the Governor's Gold Medal in an all-India exhibition in 1938. His social sympathies thus often came to be muted with the romantic's retreat into rural idylls. If Santhals figured in his watercolours, it wasn't so much as icons of struggle as of svelte grace that echoes the sensuous beauty of Nature.

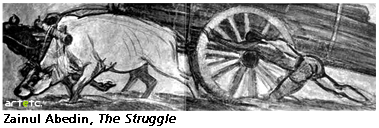

In the absence of the entire body of their works, it's difficult to define them fully, yet another difference seems to suggest itself. Though animals do find a place in Chittaprasad's tableaux, these are not imbued with individuality. In Abedin's drawings and paintings, however, cows and crows are characters. Hence, his art is less activist ardour and more a reflection of forms and the rhythm of lines that capture them in different moods. An oil that he did somewhat late in life, probably in 1976, and called Struggle shows a bullock cart toiling forward under a heavy load of logs. If the bare-bodied villager, straining every muscle to push the wheels, affirms the emotional affiliation of his young days, the bullocks, heaving laboriously, too, remind you that life's a struggle for both man and beast.

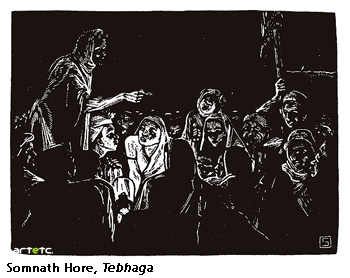

When the famine descended upon Bengal, Somnath Hore was only 22. That did not stop him from documenting the dance of death for a Communist Party journal, though. And by the time the Tebhaga stir erupted in 1946, 25-year-old Hore was ready to serve the Party with his art once more. His sketches from this period boast supple and fluent lines. But in the wood engravings that represent night scenes, you notice a deft technician at work, with a chiaroscuro treatment that captures cinematically the glow of light emanating from an unseen lantern that throws patterns of shadows to break up the faces of seated figures and leaves a looming darkness beyond.

Hore would, of course, live to become one of India's major artists, particularly with his sculpture which he preferred to call, simply, bronzes. That was because mass and volume were replaced with bronze “sheets” that wrap hollows combined with stick-like limbs, so that the skeletal economy of the prints and drawings is echoed. “Wounds were what I saw everywhere around me,” he wrote. “A scarred tree, a road gouged by a truck tyre, a man knifed for no visible reason…the object was eliminated. Only wounds remained.”

This excerption of “wounds” from his experiences takes him much beyond any ism and gives an insight into his meditation on life which is seen as a sum of suffering, approximating Buddhism. Quite remarkably, he'd moved away from the anthropocentrism of Western thought, including Marxism, to feel intuitive pain for not only lower creatures but inanimate objects, too. When he talks of a “road gouged by a truck tyre” in terms of “wounds”, they become a metaphor for the attrition of existence; or if a man is killed for “no visible reason” there's helpless despair at a contingent universe that does not have a supreme design. A position that was far removed from the ultimate dawn of Marxism.

Like all serious Indian artists of early modernity, the three had, of course, rejected European academicism. And, given their Leftist activism, they wouldn't allow Bengal School sentimentalism to creep in either. What researchers might be interested in plotting is their stylistic journey as they discovered in 19th and 20th century European art models to inspire them. Abedin may possibly have found Degas and Rouault worthy guides in his mature phase, while Matisse and Picasso seem to have influenced both him and Chittaprasad. And Hore's affinity with Kathe Kollwitz has been generally acknowledged.

It certainly seems that, of the three, Chittaprasad was the one who did not get his due. For example, there were only two shows of his art that were held during his lifetime. He shifted to Bombay (now Mumbai), stayed in a one-room apartment, lived alone, and charged modest rates for his work. As he distanced himself from the Party, politics retreated to the background in his art, with birds, still lifes and common people claiming his attention. His illustrations for children's books reveal a little-known aspect of this social and political rebel. The immensely gifted man read and wrote poetry, learnt puppetry from a Czech friend, and generally lived life on his own, not-so-usual terms.

Abedin's life had its surprises, too. With Independence for the new state of Pakistan, his role changed: from a protester he became a builder. But the political upsurge of the Bengalis urged him to protest once again but its language, after more than two decades would be very different. A 65 ft scroll done in ink, watercolour and wax, lent support to the 1969 mass movement for autonomy for East Pakistan. It was, significantly, called Nabanna, or the harvesting of the new paddy.

Both he and Chittaprasad died in their early 60s. But while Abedin had been called Shilpacharya and was able to set up institutions in different parts of Bangladesh, the latter died unsung in Calcutta, and his many talents, if at all these had been known beyond a niche group of admirers, faded from public memory.

Fortunately for Indian art, Somnath Hore and his wife Reba - very talented artist herself - had begun to concentrate more on their art than on Party activism from the 1950s. Fortuitously, he lived to be 85, though an incurable lung condition had disabled him cruelly in his final years. But by then his place in modern Indian art had been ensured. The affective images of suffering his bronzes insinuate have often been read in Marxian rather than metaphysical terms. There's no doubt that this frail, gentleman's faith in secular humanism was unshakable. But the agony of The Fallen Ox, as it lies collapsed, rib cage heaving, cannot be mitigated through any kind of ism. The face flat, mask-like, dead that seems to be sucked in by a surge of shredded bronze sheets in Flood could be the remains of a proto-human buried in some primeval stratum, arousing an ellipsis of terrible wonder at this epic and unfathomable drama called life. Old age, one of the sights that set the Buddha thinking, had drawn him repeatedly as a theme in works like The Old Man, The Old Woman, Draupadi in Old Age. For old age is a chastening reminder of transience and mortality; a reminder of the only truth that endures.