- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

Looking from the Other Side

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

Sunanda K Sanyal in Conversation with Sarina Khan Reddy

Born of an Indian father and a white American mother, Sarina Khan Reddy is a new face of South Asian immigrant culture in the United States. Among other things, her new media work deconstructs the hegemonic underpinnings of American world view. I met with Sarina at a café in Newburyport, Massachusetts, to talk about her life and the sharp political edge that defines her art.

Born of an Indian father and a white American mother, Sarina Khan Reddy is a new face of South Asian immigrant culture in the United States. Among other things, her new media work deconstructs the hegemonic underpinnings of American world view. I met with Sarina at a café in Newburyport, Massachusetts, to talk about her life and the sharp political edge that defines her art.

Sarina Khan Reddy: My father was born in Bhopal, north India. He came here for his Ph.D. and decided to marry and stay in this country, against his parent's wishes. I was born here. My mother is American. So I guess I am first-generation Indian-American. And as with most Indian parents, my father always said….”you will be a doctor or an engineer”…

Sunanda K Sanyal: Did you go back to India to grow up?

SKR: We went every summer. I have over forty cousins in Bhopal, Bombay, and Delhi. I am very close to my Indian family. Later in life, I studied engineering (as my father expected), and after my Master's degree in Chemical Engineering, I started working for Eastman Kodak in R&D. I am still working there, now as a project manager and software developer. But I've always been interested in art. So early on, while I was creating technology at Eastman Kodak, I decided that I would rather be the artist who uses technology creatively. So I thought it was a long shot, but I applied to grad school for an MFA. I don't have an undergraduate degree in art, but thought I'd apply and see what happens. At the time, I was working with a non-profit foundation in south India that was helping the local poor population; and they were also making multimedia CDs of some of Indian mythologies / mantras / deities, etc. So I was working for them and at the same time thinking what I would put in my portfolio; and then it dawned on me. This multimedia along with other work, gave me acceptance to grad school. I was quite excited to get into the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and even more excited when I received my MFA in 2003.

SKS: So you're one of those hybrids with regard to your art education?

SKR: Hybrid, yes! Yeah, undergrad and graduate degree in Chemical Engineering, and then I went back for a graduate degree in art. And the Museum School is perfect, because they let you do a little bit of everything; you don't have to concentrate in one field. I was able to take printmaking, video, installation etc. The school is very theory-based, which was fabulous for me! You really are able research in depth what you're interested in and then look for the best medium to implement the ideas. For example, I have always loved Indian design, and the exotic, and all of that. But when I got to grad school, their first question was, “Well, why do you like it?” So it was the first time that I really started to critique and take apart….investigate what is the “Other”, what is Orientalism…

SKS: Did you get theoretical training before you went to grad school?

SKR: No, but I had always been very political, and read a lot. Also, as an engineer, I think we tend to analyze and take things apart….

SKS: But engineers don't typically read Baudrillard and Derrida. So I'm wondering what led you to that.

SKR: Well, I've always been extremely politicized. I have always loved Noam Chomsky and have heard him speak many times at MIT. When you're looking at politics, you need to deconstruct things. So when I got into art school, I took a literary theory class. And when they started talking about Marx, I thought this is the way I have always thought! It's just that I didn't have words or labels for it. And I was thinking, why didn't I study literary theory so long ago?

My MFA thesis show was entitled: The Great Game: A New World Order? (2003). It is a three-channel video, which explores the new colonization embodied in globalization. Through comparative strategies, the viewer is asked to examine the differences between the current glorification of US war technology, the past glory of the British Empire, and the glamorization of the 3rd Reich as expressed in the Nazi propaganda film, Triumph of the Will. The items within the installation are an important part of the artist and her extended family's homes. Most of the sepia photos are of the artist and her family.

SKS: Do you think there is a fundamental difference between the sensibility of an artist of South Asian origin who came here as an adult and one who was born here?

SKR: I think the important question is: Does an artist identify as diasporic? And if so, the artist embodies the paradoxes of being an American and being part of the South Asian Diaspora. I see myself as being Western and Eastern, being the colonizer and the colonized. Critically analyzing colonialism and at the same time desiring a discredited history. These paradoxes can reveal the remaking of a culture and counter what is out there in the mainstream. I question the US role of imperialism here in this country. And in India, I question the effects of colonialism. I feel I address in my work the problematic of the American love for India for its exoticness. So being an American, I deconstruct that desire; look at the theory behind it.

SKS: So you're suggesting that South Asian artists who are born here have the advantage of belonging here, so that they can “look” at the “look” of the West at the Other?

SKR: Exactly. And I think the diasporic artist has the unique ability to question the dominant paradigm.

SKS: Yes, generally speaking. But I'm trying to locate a difference between a diasporic artist who has spent half of her/his life in India and someone who was born and raised here, one who has the advantage of “looking” at the “look”.

SKR: I think if you have spent half of your life in India, you're going to be more likely to critique India and glamorize the United States. I, on the other hand, critique the American agenda harshly and at the same time critique my desire for the “exotic India”. A lot of people are very offended by my work; they think it's very anti-American. But I feel if you're not an American, you're less likely to do that, you know.

SKS: Now, having been born and raised here, how do you see your own gaze at India? You're kind of an “outsider” there, right? How do you reconcile that?

SKR: Well, I don't feel I have the ability to handle themes like the Pakistan-Indian conflict. I feel that if I showed a work in India on such theme, that'd be problematic because I don't know that problem so well.

SKS: Did your father have particular ideas about raising you?

SKR: Yeah. But he wasn't religious, which was a great thing. But socially, he was very, very Indian.

SKS: Especially because you're a woman.

SKR: Well, yeah. I wasn't allowed to date until I was in college. And he wanted to have an arranged marriage on one hand, but he also wanted me to be a highly successful engineer and my own person.

SKS: So he was torn?

SKR: He was very torn. So when I met Prakash, I said, “You must be so happy because he is Indian.” But he pointed out that he was Hindu. And then he also added that we are not a very religious family and that the values of all Indians are the same and that is the most important thing. And finally he said, “You are living in the US, so this is a non-issue, but if you were living in India, it would be a big problem.”

SKS: It'd be interesting to see what he would say about the kind of art you make. He never saw you go to graduate school.

SKR: Yes. But he knew I was interested in art, although he thought of it as a hobby.

SKS: But the content…

SKR: He would love the political content. He was very, very left wing.

SKS: And what about your mother? What kind of say did she have in your culturally hybrid childhood?

SKR: My mother, on the other hand, was very liberal. She exposed me to the arts and gave me the passion for hiking and skiing. These were not that important to my father. I am very glad that I was influenced by the values of both cultures.

SKS: When something is framed by the current discourse of art, do you think it's too aestheticized to carry any political message?

SKR: Yes, it's appropriated by capitalism. But because I don't have an undergraduate art background, I try to use a lot of mainstream media. So I hope more people understand it. I think the important thing is for the viewer to learn to critique. To be able to analyze, which is something not taught in our culture. So if they can just start to question…that's what I think political art allows the viewer to do at the very least, not just propaganda. It attempts to show the layers underneath. You might not agree with what I'm saying, but at least it's making you think how propaganda is given to you. I don't want to give more propaganda; I want you to question propaganda, and peel away the layers. I want you to know that there is an alternative way of looking and critiquing everything.

SKS: What about your projects through the last decade?

SKR: I am working on several projects in video and installation. I also have several photography series that I have been working on over the last several years.

SKS: What about the one involving Disney World?

SKR: I became very interested in architecture, how we create unreal spaces, whether it's Las Vegas or Disneyland. The hotels in Florida advertise Disney World as “You can go to India, without getting Malaria”. Some people came to my show and said: “Yeah, I was there! Cambodia, right?…” And I said, “No! This is Florida!” Disney World is the most visited vacation destination on the planet. Annually 46 million tourists visit the Orlando area. So I decided to do a project there.

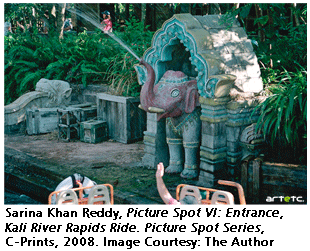

In the series of photographs entitled Picture Spot (2008), I explore the perpetuation of the colonialist image, the construction of the exotic, in Disney's theme park-- Animal Kingdom. I ask the questions: What is authentic? What is the role of photography in tourism? What happens when you construct a scene (a spot) for a tourist snapshot? Does this perpetuate the construction of the other?

SKS: So your point is to confuse the viewer, to make the case that simulations look real in photographs?

SKR: Yes. I didn't change anything in the photos. At first glance, they are typical tourist photos of South Asia. But then, you notice – a pasty white arm waving from a plastic paddle boat, a handicap accessible symbol on a rickshaw, a McDonald's French fry container crudely painted on a stucco wall- and the scenes begin to morph disturbingly before our eyes. These small clues hint at the crisis of representation that the series explores. It becomes clear that we're looking at a simulacrum of exotic Asia, a life-sized diorama, inscribed with colonialist quaintness.

SKS: Your photos even show how English words are often spelt incorrectly in India.

SKR: Yes, they re-wrote them! That's unbelievable! Disney has created the third world that was always targeted by imperialism-climate controlled, easily escaped, conveniently free of 'natives' and catered by McDonald's.

SKS: Any contemporary artists who interest you, and why?

SKR: Recently I saw a show entitled Six Artists from Cairo at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and heard a lecture by one of the artist, Shady El Noshokata. His work was very interesting about what identity is. And what an artist is. I also am interested and have been influenced by Marina Abramovic, especially by her recent show at MoMA, The Artist is Present. One very powerful performance of open-eye mediation she did with viewers has brought up a lot of aspects of ancient Indian spirituality that I am looking at in my latest work.