- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

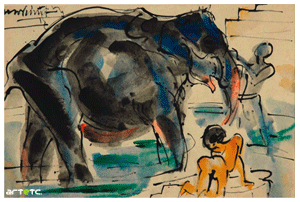

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

by Pranabranjan Ray

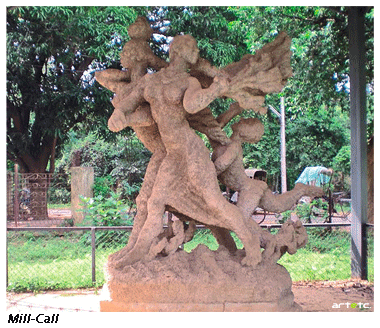

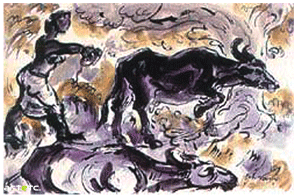

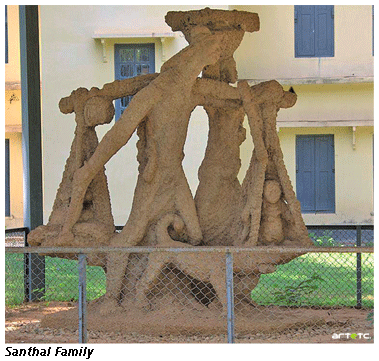

In Visva-Bharati's, Kala Bhavana campus, in Santiniketan, among others, there is a sculptural ensemble, comprising an adult male and a female - obviously a couple, with the female holding a child on to the left flank of her body with her left arm, while the male is carrying the other child sitting on front-side basket-balance of the weighing-scale hanging from the bamboo pole carried by the man on his shoulder. A dog struts along side. As it comprises more than one figure standing on a base, in close physical relation, it should be called a sculptural ensemble. The figures are one-and-a half times larger than their real life equivalents.

It is evident, from the scanty body-clinging thin clothings which barely cover the erogenous areas of their youthful bodies and the nakedness of the children, that it is an extremely poor family. From the accessories and the manners of carrying those, like the bulk weighing basket-balance hanging from bamboo-rod being carried from shoulder by the male, with his thin cotton-woven all-purpose gamchha now going up his head like a turban, and the female balancing a smaller basket full of essentials topped by a rolled up mat they had spread on ground for resting, make the family out to be a rural subsistent level agriculturist family. The suggestion clearly is that the family had taken three basketful of primary produce of land to the market and waited there to sell those for procuring small amounts of processed essentials, with the proceeds of the sale. From their physiognomy and the ubiquitous company of the dog, it is apparent that they belong to the Santhal community, one of the larger autochthonous communities of eastern India, known for its expertise in dryland cultivation. The sculptor, Ramkinkar Baij (1906-'80), himself had willed the family to be identified as a Santhal Family. Hence, the name.

It is evident, from the scanty body-clinging thin clothings which barely cover the erogenous areas of their youthful bodies and the nakedness of the children, that it is an extremely poor family. From the accessories and the manners of carrying those, like the bulk weighing basket-balance hanging from bamboo-rod being carried from shoulder by the male, with his thin cotton-woven all-purpose gamchha now going up his head like a turban, and the female balancing a smaller basket full of essentials topped by a rolled up mat they had spread on ground for resting, make the family out to be a rural subsistent level agriculturist family. The suggestion clearly is that the family had taken three basketful of primary produce of land to the market and waited there to sell those for procuring small amounts of processed essentials, with the proceeds of the sale. From their physiognomy and the ubiquitous company of the dog, it is apparent that they belong to the Santhal community, one of the larger autochthonous communities of eastern India, known for its expertise in dryland cultivation. The sculptor, Ramkinkar Baij (1906-'80), himself had willed the family to be identified as a Santhal Family. Hence, the name.

When installed in 1938, in open space, on a ground-level concrete base, on a plot of prickly grass on degraded red Lateritic soil of the semi-arid Rarh region of western Bengal, the ensemble stood just fifty feet to the south of, a twelve feet wide dusty red road, paved with lateritic granules, gravels and earth. The ensemble with its back to the east faced the setting sun in the west -parallel to east to east-west alignment of the road. The Santhal Family, thus seems to have been conceived as a site-specific sculptural assemblage. In its present state, with a canopy overhead and a protective barrier around, rows of building within a viewer's field of vision and the road made tar-macademised with black top, the ensemble has lost its site-specificity. But it still adorns Visva-Bharati's Kala-Bhavana campus, which Ramkinkar had set out to do at the bidding of the founder, Rabindranath Tagore himself. And to Tagore and his visva-nidham he owed a debt for widening his mental and intellectual horizon and combining that with intensification of response to experience of here-and-now.

When installed in 1938, in open space, on a ground-level concrete base, on a plot of prickly grass on degraded red Lateritic soil of the semi-arid Rarh region of western Bengal, the ensemble stood just fifty feet to the south of, a twelve feet wide dusty red road, paved with lateritic granules, gravels and earth. The ensemble with its back to the east faced the setting sun in the west -parallel to east to east-west alignment of the road. The Santhal Family, thus seems to have been conceived as a site-specific sculptural assemblage. In its present state, with a canopy overhead and a protective barrier around, rows of building within a viewer's field of vision and the road made tar-macademised with black top, the ensemble has lost its site-specificity. But it still adorns Visva-Bharati's Kala-Bhavana campus, which Ramkinkar had set out to do at the bidding of the founder, Rabindranath Tagore himself. And to Tagore and his visva-nidham he owed a debt for widening his mental and intellectual horizon and combining that with intensification of response to experience of here-and-now.

The ensemble is made of lateritic granules and gravels, from the degraded lands, called khowai in local parlance, available freely from around the site; mixed with just enough cement to bind the makra pathar- the mix gives a granuler feel on the surface.

The family is on their way back from the nearest market place and is hurrying homewards. They evidently took basketful of home produce, waited long by spreading a mat on ground, to sell them off at distress price, to buy some primarily processed necessities like salt and oils, and return home with relatively dear essentials all in a small basket, balanced on her head by the woman with her raised right hand. The act of balancing the load on head with right hand, makes her upper body more erect, in contrast to the male partner, and her youthful motherly fully rounded breasts move forward with each stride. All these situational and quantitative information can be derived by reading and following the indications thrown up by the images of the named objects and features, in the manner those have been presented. Thus read, these function as signifiers. The family is in a hurry to get back home before the dusk descends. Significantly again, they are heading towards setting sun with their back to the east.

The hurried movements get visualized through the gap between 'forward placings of the left legs of the couple and their right legs about to be raised from their former positions in their strides forward; the woman's right leg gets a little bent at the knee, when the man's right leg bends a little with bulging calf muscle. Both their left legs stride straight forward in strength. The legs form triangles with solidly grounded base to hold the waist-up bodies. Commensurate with the forward striding movement, the right arm of the male swings back straight, at a 50° angle to the ground, holding a string from which hangs the basket at the back from the pole carried on the shoulder. This hand-swing gives a diagonal thrust to the forward movement and speeds it up. The weary left hand of the man rests on the front part of the weighing pole after breaking at the elbow to form a horizontal to the ground triangle. The elbow touches the sheen of the spouse, just below her right breast. The quite out of proportion elongated forward bending neck expresses an eagerness to go faster. The slight spouse-ward leaning male head, on the neck, has been carved with more expressive details than the rest of the body, to express a combination of weariness, eagerness and anxiety alternately - depending on the viewer's angle of viewing. Such an excellence in visual execution of conception was reached only once in India, in the Gupta era. But Ramkinkar's achievement is greater. Unlike the sculptors of Mathura and Sarnath, Ramkinkar could combine the expressions of several conflicting emotions with vital physical action, and that too with far more coarse material than the very fine grained Mathura sand-stones the earlier sculptors had worked with. To return to the ensemble itself, weariness and anxiety notwithstanding, the poor young Santhal couple moves resolutely forward to the security of home, especially for the children. Although their movement forward appears somewhat circumstantially compulsive and destiny driven, yet their striding confidence and countenance, especially of the woman, suggest as though they are energized by a youthful life force, of which sexuality is an aspect. The last bit is not an over reading; the bodily signifiers are there. .

A very important noticeable aspect of the vital dynamics is the rhythmicity of the movements visualised. While the synchronised movement of the straight linear falls and rises of the legs gives out a staccato rhythm of almost drilled togetherness, the child encircling left arm of the women and the languid left arm of the man resting on the horizontal pole, give to the middle-upper part of the body a harmonised ripple movement comprising two different kinds of rhythms - animating the bodies. The erect trunk of the woman and the slightly forward bending trunk of the upper body of the man balances two opposing rhythms to build up a complimentarity. The rhythmic presentation of movement, in the sculpture, thus, seems to have a suggestive function, apart from its function of uniting the ensemble and accentuating the quality of movement. Without this variation of rhythms in the different parts of the three bodies (the dog included), the artist could not have expressed his mixed feelings and layered the comprehensions of meaning. At the end of the story, it is the visual transfer of artist's response, in terms of image, to worldly experience. The meaning content of it is more important than the phenomenon the ensemble represents.

What we have done so far, is a descriptive analysis of the visual data contained in the Santhal Family. This by no means gives full idea about the historical importance and the intrinsic greatness of one of the most significant signature work of Ramkinkar, done by the 1906-born artist, when he was just thirty-two. What we need to do now, is to go into a discourse on the intrinsic quality of the sculptural text, giving due importance to the historical context. In doing so, we shall enter the ensemble through the physical data it provides.

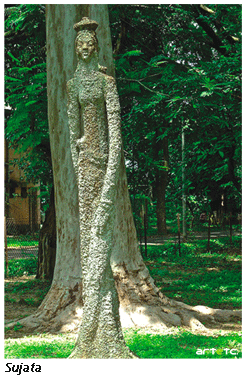

This sculptural ensemble is one of the earliest on different counts, as we shall slowly discover as we proceed. Take the material and method first. The medium basically is cement-concrete. It was developed, in Europe in the cold-war years just before the First World War of 1914-18, for construction of solidly standing high defensive constructions, like the Maginot Line and the Siegfried Line. In the immediate post-war period, it led to the boom in skyscraper construction in the USA. Yet, in so far as I know, no major Western sculptor thought of using it as a medium of sculptural expression. The cement-concrete as a constructional material began to be used in India from the early thirties only. That makes Ramkinkar the first sculptor in India, and one of the pioneers anywhere, to have innovated the use of cement-concrete as a medium of art. Even if someone, somewhere had used the medium before him, the materials he processed to make his medium, and the methods he employed to construct his imagery, were innovated entirely by him. Instead of stone chips and sand, he used lateritic granules, gravels and coarse lateritic earth; mixed the whole thing up with just enough cement needed for binding and bonding the mix. He had used this particular mix of ingredients, for the first time in 1935, to make an eleven-feet high slim open-air sculpture, in the same campus which he titled Sujata. It had a difference in structure. All concrete constructions need armatures or skeletal supports from within, for the concrete mix to grip and hold on to. In Sujata, he had used bamboo poles and splits tied with canes for armature - the cheapest material for him. But for erecting such an elaborate and complex ensemble as the Santhal Family, he found the material unsuitable. He, therefore, opted for an iron rod and steel wire armature, grounded to the foundation. Two years hence, in 1940, he would be making a smooth-surface sculpture with a compound of colour mixed white cement, stone chips and sand, in reversed proportions, on a skeleton made with iron pipes and steel wire. That was designed to function as a lamp stand, in the open. It is very much an abstract composition on the theme of rhythmic correspondences between floromorphic growth and human dance. It demands to be recognised as the earliest example of visual objectification of an abstract idea in Indian art, of the modern period of history.

This sculptural ensemble is one of the earliest on different counts, as we shall slowly discover as we proceed. Take the material and method first. The medium basically is cement-concrete. It was developed, in Europe in the cold-war years just before the First World War of 1914-18, for construction of solidly standing high defensive constructions, like the Maginot Line and the Siegfried Line. In the immediate post-war period, it led to the boom in skyscraper construction in the USA. Yet, in so far as I know, no major Western sculptor thought of using it as a medium of sculptural expression. The cement-concrete as a constructional material began to be used in India from the early thirties only. That makes Ramkinkar the first sculptor in India, and one of the pioneers anywhere, to have innovated the use of cement-concrete as a medium of art. Even if someone, somewhere had used the medium before him, the materials he processed to make his medium, and the methods he employed to construct his imagery, were innovated entirely by him. Instead of stone chips and sand, he used lateritic granules, gravels and coarse lateritic earth; mixed the whole thing up with just enough cement needed for binding and bonding the mix. He had used this particular mix of ingredients, for the first time in 1935, to make an eleven-feet high slim open-air sculpture, in the same campus which he titled Sujata. It had a difference in structure. All concrete constructions need armatures or skeletal supports from within, for the concrete mix to grip and hold on to. In Sujata, he had used bamboo poles and splits tied with canes for armature - the cheapest material for him. But for erecting such an elaborate and complex ensemble as the Santhal Family, he found the material unsuitable. He, therefore, opted for an iron rod and steel wire armature, grounded to the foundation. Two years hence, in 1940, he would be making a smooth-surface sculpture with a compound of colour mixed white cement, stone chips and sand, in reversed proportions, on a skeleton made with iron pipes and steel wire. That was designed to function as a lamp stand, in the open. It is very much an abstract composition on the theme of rhythmic correspondences between floromorphic growth and human dance. It demands to be recognised as the earliest example of visual objectification of an abstract idea in Indian art, of the modern period of history.

To go back to the main discourse, let us now look at the technique Ramkinker had adopted to accomplish the self-imposed task. After tying the armature to a skeletal approximation of the final form, the sculptor would take fists full of the concrete mix of desired consistency (moisture content) and start throwing those for piling up at selected portions of the erect armature; with a crudely made scalpel he would scrape off excess of unwanted concrete while the mix is yet to dry, to bring out the shape. Upto this stage of operation, Ramkinker's techniques were akin to the additive mode of the clay idol makers' of his native Bankura, whom he had observed at work in his adolescence, before moving to Santiniketan. But what he would do next, would be what the stone carvers do. After proper drying of the mix, with a hammer driven chisel, he would painstakingly carve out - accentuated details of physiognomical characteristic features of ethnic identity and age-group, in the first place. The second function of such intensive carving would be capturing the mental state, of the characters - perceived by the sculptor - as get expressed through subtle changes in the physical features. To make the expression perceptual enough, the sculptor of the ensemble in discussion, clearly had taken recourse to gestural accentuation of featural changes, coupled with very subtle smoothening out of anatomical details from those parts of the body not needed. But, the most significant aspect of the treatment has been the carvings, for getting the feel of rhythm of movement. The markers of contrasting rhythms of forward stride and tired drag, suggesting eagerness and anxiety at the same time, can easily be seen all over the ensemble. To achieve such effects with an experimentally arrived at medium, was not a convenient matter. We need to enquire as to why the sculptor had chosen to walk the path.

Was Ramkinkar driven by a will to adapt the newly developed construction technology for expressional purposes only? Why then he changed the ingredients? Was this change needed as a cost-cutting measure only? Execution of such a big project at a minimum cost definitely was the first parameter. Execution of an ensemble of similar dimensions in any conventional sculpture-making medium would have multiplied the cost several times over. Like all other art for public viewing in the Visva-Bharati campus, the Santhal Family too was not a commissioned work. Visva-Bharati then had no means to commission. Tagore had to beg, borrow and pay from his royalties to run the cash-starved institution. Visva-Bharati could barely manage to meet the minimally expensive inputs. For the artist it was a labour of love. But the bigger question is, was the choice conditioned by lack, of fund only? It does not seem so. A deeper motivation might have been to give to the represented bodies of the sons and daughters of soil the look and the feel of the soil on which they toil and move. Only in terms of this will, his experiment with untried ingredient for making cement-concrete can be accounted for.

Another pertinent observation needs to be made on the use of the materials and methods which perhaps was to establish the prime truth that the ensemble, by no means, is a surrogate of a phenomenon. While there should not be any doubt about the fact that the constructed subject was the resultant effect of Ramkinkar's deep empathy for the toiling daughters and sons of the soil and experience of their modes of living, he had the other - no less urgent-desire to construct the ensemble as a distinctive entity and not just a representation of a probable event. The chosen medium and the methods adopted were ideal for making the distinctinction physically perceptible; subtler treatment which took the distinction further would only follow.

Another pertinent observation needs to be made on the use of the materials and methods which perhaps was to establish the prime truth that the ensemble, by no means, is a surrogate of a phenomenon. While there should not be any doubt about the fact that the constructed subject was the resultant effect of Ramkinkar's deep empathy for the toiling daughters and sons of the soil and experience of their modes of living, he had the other - no less urgent-desire to construct the ensemble as a distinctive entity and not just a representation of a probable event. The chosen medium and the methods adopted were ideal for making the distinctinction physically perceptible; subtler treatment which took the distinction further would only follow.

The descriptive analysis we started with and the discussion on the materials and methods we initiated inevitably lead us to a further probe into the subject matter, a part of which we have already covered. Let us re-view the ensemble, once again. While describing it in details we have just stopped short of saying that the ensemble narrates a story. The narratology includes the very perceptual present, with suggestions of the precedent and the antecedent, revealed through use of visible indicators and markers strewn all over the body of the ensemble, as we have taken notes of, through our viewing of the work. Reading the subject matter with due importance given to the suggestions signaled by the indicators and markers, makes the beholder aware of a deep theme that had motived the maker of the ensemble as it appears to the eyes. With such an awareness dawning, the very perceptible subject matter appears to be a construction, an objective correlate as T.S. Eliot would have maintained. The subject is the artist himself, his response to his experience of life-and-nature. This ensemble, like most of Ramkinkar's yet to be made later work, is an expression of his realization of dynamic interactivity between various forces of life and nature. It is also to be seen as an expression of his own psychological responses to different manifestations of this dynamism. He rejoices the manifestation of elan vital that moves the youth to forward positions, to procreate and make the earth fertile with their joyous labour. Manifestations of forces of retardation like the spread of soil-degradation, tiring fruitless toil on degraded soil etc. make him anxious. Ramkinkar's Santhal Family, is a sculptural ensemble that expresses, as if with supreme ease, a complex mix of conflicting emotional response, to a long experience of life-and-nature.

For the present, I am refraining from an assessment of the ensemble's significance in the socio-cultural history of modern India. I have already given some hints in my discussion on this aspect.