- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

by Koeli Mukherjee Ghose

Reading of Benodebehari's work from the essay The Integrative Vision by Paranabranjan Ray, along with references from writings of K.G. Subramanyan, and R. Siva Kumar.

Sri Pranabranjan Ray in his essay, The Integrative Vision published in, Pratikshan Essay in the arts 1- Bengal Art - New Perspective, throws open a conspicuous debate at the very beginning of the essay, that pitch for perspicacity in Benodebehari's stance from that of Nandalal and Ramkinkar, with reference to contextual response of the three artists in relation to their times and its reflection in their works. For a better understanding of the artist Benodebehari, the author navigates through Benodebehari's creative work, along with his discursive writings.

Sri Pranabranjan Ray in his essay, The Integrative Vision published in, Pratikshan Essay in the arts 1- Bengal Art - New Perspective, throws open a conspicuous debate at the very beginning of the essay, that pitch for perspicacity in Benodebehari's stance from that of Nandalal and Ramkinkar, with reference to contextual response of the three artists in relation to their times and its reflection in their works. For a better understanding of the artist Benodebehari, the author navigates through Benodebehari's creative work, along with his discursive writings.

He mentions “Benodebehari Mukherjee is often quoted as saying that unlike his teacher Nandalal Bose and contemporary Ramkinkar Baij, he was never drawn to the politics of the time, and that his objective was to be creative.” Rays findings from Benodebehari's writings of the artist's interpretation of himself as an aesthete also surfaces with the fact that Benodebehari was not complacent to the colonization affecting the art and culture during his time either. Ray points out that “the fairly large corpus of Benodebehari's Bengali and English writings, very few of which have been anthologized, on the state of the visual art and crafts in British India, We learn how greatly interested he was in the question of cultural contact in the overarching situation of domination-subjugation, hegemony-acquiescence.” Here Ray has clearly denoted the underlying sensibility at work for Benodebehari in deciding to paint in a certain manner and what he thought was important for him to paint.

At the backdrop the influence of the British rule was full to overflowing; Benodebehari was fully aware of the contradictory options that branched out as an outcome of the Imperial domination on cultural expression and that of a sense of activism against the infringement of rights for a National identity but Benodebehari, chose to stay away from either and be free to amalgamate his creative responses to the life around him that changed considerably due to the meeting of two different cultures; the Indian and the British.

The possible permeation of Tagorean sensibility, as part of Benodebehari's education in Santiniketan in 1917, when he was twelve, cannot be ruled out. During this time Tagore was focused towards building on the foundation of a holistic science of education and the correct use of instructive strategies in Santiniketan rather than being on an overt nationalistic drive against colonization.

A discerning look at Benodebehari's attention and study of ordinary people, going about their chores, in their natural and habitual surroundings, nature's reward expressed in flowers and trees, cheering those who are forlorn and at times the pleasing vista, for cherished connection between people, found expression as either transitory or enduring - as subjects, and emerged in his works and all these reflect; life and its manifestations. - This validates Ray's findings, as he points out “with an absolute lack of interest in mythology, iconography and ritualistics” and since mythology, iconography and ritualistics, are elements that were fundamental to and a characteristic feature of the Nationalist's language and projection of ideals through artistic impetus, that which defined the artistic panorama of Benodebehari's time.

A discerning look at Benodebehari's attention and study of ordinary people, going about their chores, in their natural and habitual surroundings, nature's reward expressed in flowers and trees, cheering those who are forlorn and at times the pleasing vista, for cherished connection between people, found expression as either transitory or enduring - as subjects, and emerged in his works and all these reflect; life and its manifestations. - This validates Ray's findings, as he points out “with an absolute lack of interest in mythology, iconography and ritualistics” and since mythology, iconography and ritualistics, are elements that were fundamental to and a characteristic feature of the Nationalist's language and projection of ideals through artistic impetus, that which defined the artistic panorama of Benodebehari's time.

Benodebehari's complete bypassing of these elements is what makes the author cogitate upon the fact that perhaps the introduction to Tagorean thought as part of Benodebehari's didactic upbringing in Santiniketan and his responsiveness towards it reflected in his art and the thought behind it to be individualistic and free in his response.

Benodebehari wrote, “whatever is significant in my life, has found expression in my painting, without seeing my paintings no one can know my life's essence.”

Ray calls to mind the year 1919, the time Benodebehari went to study in the newly established Kala Bhavan, the very next year Nandala Bose took charge and in 1921 the Gurukul school evolved into Visva Bharati, “bringing the world into one nest”. He informs that The Academic plan that Rabindranath and his likeminded associates had drawn at the inception of Visva Bharati was focused on attainment of knowledge of inspiring achievements from different parts of the world, of different historical times that which is free from the repression of needs and its diffusion. In the context of Kala-Bhavana this model had a unique implication. According to Rabindranath, creativeness is the bountiful energy which is not bound to just securing skills or grades to earn a livelihood. While in opposition to the British dominion on culture, as the Nationalist movement for the political sovereignty progressed, it also created indicators for cultural distinctiveness, for the nation, on the basis of undeniable ethnicity and customs, advocating their inclusion into artistic engagement, In reality the progress for political autonomy, was tying creativity to obligations and opposing the lack of, that was restrictions for making choices that is necessary for creativity.”

Ray mentions – “Talking about the influence of art on art practice, Benodebehari could have asked, and indeed in many of his writings has implied as to when art had not been influenced by art, as also by non-art factors. As long as influence remained unilinear, i.e. confined broadly within one cultural tradition, very few would recognize that as an influence. But as soon as inspiration and linguistic devices began to be applied, the influence came into prominence. But the arts of societies in transition-through the struggle between colonialism and nationalism, from a herd -mentality to the discovery of the Individual, from consanguinous solidarities to democracy-were destined to be eclectic. The moot points to consider are: (a) whether the artist is appropriating elements, devices and ideas he / she considers as relevant and significant; (b) whether the artist is being able to internalize and transform the borrowed items and (c) integrate the loaned elements sufficiently to give the created art an organic wholeness.”

At the earliest point of his artistic calling, Benodebehari began his landscapes of locations from his native place of Pabna district for example Padma-Jamuna basin, he also drew and painted on the site of creased landform of the khowai of santiniketan and the rural surroundings along the winding river of Kopai. Ray defines the works as essentially “not description of places with natural and constructed features. To call them impressions, in the Impressionistic sense, would also be misleading, although these indeed were impressions.” The significant features of Benodebehari's work were suggested by lines which were boundless and flowing rather than contour defining, that emphasized their rhythmic excellence. Other than the relative proportioning of the physical features by rendering contour lines, the effective positioning of unconnected lines on the plane instantaneously validate a sense of spatial distance, creating a unique space.

At the earliest point of his artistic calling, Benodebehari began his landscapes of locations from his native place of Pabna district for example Padma-Jamuna basin, he also drew and painted on the site of creased landform of the khowai of santiniketan and the rural surroundings along the winding river of Kopai. Ray defines the works as essentially “not description of places with natural and constructed features. To call them impressions, in the Impressionistic sense, would also be misleading, although these indeed were impressions.” The significant features of Benodebehari's work were suggested by lines which were boundless and flowing rather than contour defining, that emphasized their rhythmic excellence. Other than the relative proportioning of the physical features by rendering contour lines, the effective positioning of unconnected lines on the plane instantaneously validate a sense of spatial distance, creating a unique space.

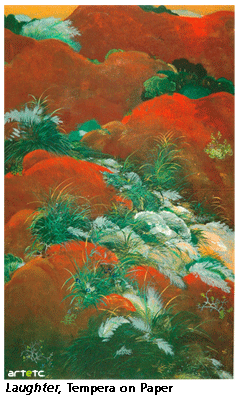

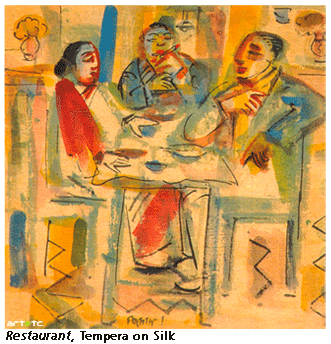

In his temperas,of the mid thirties globular drops of colours from the brush drunk with colours, rendered the foliage, the rugged landforms and the human form expressed with a rhythm, rendered a figurative quality. The sweeping calligraphic lines and its interplay with the forms perhaps appear expressionistic, but Ray elucidates that “One may only be partially right to assume that. In his use of both masses and lines there was nothing of hurried gesturalism; all indicators were carefully crafted to represent phenomenal entities, but only as summaries.”

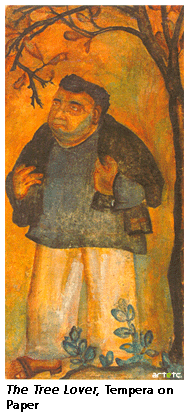

One fine exemplar of his earlier accomplishment in assimilating appropriated rudiments selectively as Pranabranjan Ray describes – “The almost iconic portrait of his Tree Lover colleague Tejeschandra Sen, that Benodebehari painted, in tempera, in 1932 is a remarkable non ceremonial portrait, wherein the rendering of the standing figure is resultant of a sensibility to capture the characteristic features of the personality at a point of time. It is an example of an artist's personal assessment of another person, constructed by fusing the Japanese mode of minimal delineation of contours, with caricaturish overstatements and understatements of selective limb-postures and gestures developed by the expressionists.”

An early attention to the knowledge of representation of the visually discernible unique world, prompted Benodebehari to study Far-Eastern art and not a realistic representation of the copied world. He felt that the discreet representation of the phenomenal world that Far-Eastern art offers “makes art intrinsically worth”. His interest in Far-Eastern art took him to China and Japan in 1936-37. He studied the plant life and tried out a range of support surfaces, with Chinese and Japanese colour pigments and solvents. By using instruments brought from there, he illustrated the techniques he had learned and also used the Chinese and Japanese tools. But before long, he demonstrated his unique way of using the tools and techniques. This he figured out in his own practice and emerged with a flourish to deal with, the challenge of imagining the phenomenal space on the picture plane, further activating it with evocative images and subtle trace of narratives. “He first tackled all these issues even before his Far-Eastern sojourn in a mural he did on the ceiling of the Kala Bhavana boys' hostel. “Benodebehari did a mural in a tapered and interrupted space of the staircase walls in Cheena Bhavana after he returned from his visit to the Far East. Equipped with his new earned skill he composed a depiction of the Santiniketan ashramites of the early forties, engrossed in their pursuits. It success fully indicated moving figures and through permutation of lines, gesturally shaded masses, he united a spreading composition with a sense of rhythm.

An early attention to the knowledge of representation of the visually discernible unique world, prompted Benodebehari to study Far-Eastern art and not a realistic representation of the copied world. He felt that the discreet representation of the phenomenal world that Far-Eastern art offers “makes art intrinsically worth”. His interest in Far-Eastern art took him to China and Japan in 1936-37. He studied the plant life and tried out a range of support surfaces, with Chinese and Japanese colour pigments and solvents. By using instruments brought from there, he illustrated the techniques he had learned and also used the Chinese and Japanese tools. But before long, he demonstrated his unique way of using the tools and techniques. This he figured out in his own practice and emerged with a flourish to deal with, the challenge of imagining the phenomenal space on the picture plane, further activating it with evocative images and subtle trace of narratives. “He first tackled all these issues even before his Far-Eastern sojourn in a mural he did on the ceiling of the Kala Bhavana boys' hostel. “Benodebehari did a mural in a tapered and interrupted space of the staircase walls in Cheena Bhavana after he returned from his visit to the Far East. Equipped with his new earned skill he composed a depiction of the Santiniketan ashramites of the early forties, engrossed in their pursuits. It success fully indicated moving figures and through permutation of lines, gesturally shaded masses, he united a spreading composition with a sense of rhythm.

In 1946-47, Benodebehari completed his most exceptional mural project that established him as a figural painter, on the three walls of Hindi Bhavana, in Santiniketan. Depicting the medieval saints of India, many of whom had been from the peasantry and professions of crafts and laborious work. But each of the saints in their poetry, music and teachings extended the significance of love, devotion and mutual aid as an alternative to ritualistic practices, in order to bring down the barriers of division based on religion and cast.

Ray illuminates that “With Rabindranath's active encouragement, from the twenties, Santiniketan scholars like Kshitimohan Sen, Bidhusekhar Sastri, Haridas Mitra, Sukhamay Sastri, Hazariprasad Dwivedi and others were engaged in researches on Kabir, Dadu, Nanak, Namdas, Gaudiya Vaishnavism and variations of Ramkatha, etc. In the background of the communal politics of India, which culminated in the Calcutta, Bihar, Noakhali and the Punjab riots of 1946-47, leading to the partition of India in 1947, the non communal mode of religiosity, assumed significance. All these factors seem to have played their part in Benodebehari's choice of subject matter. But the problems at Benodebehari's hands were many.”

“…. In the representation of the individual saints Benodebehari hardly ever attempted to give an individual identity, except by means of iconological attributes. He would, however, give indication of their places of activity, by placing indicative images around each of their figures; configurated in separate niches… served the purpose of representing them as individuals from different backgrounds and from different times. The niches or the surrounding space of each saint are placed at differing height with figures varying in size, suggesting their actual spatio-temporal distance.”

The placement of each of the saints in the mural is conceptual. He flowed with the rhythm of the irregular niches that provided him with vertical spaces to work on; he avoided building enclosures and enhanced the interplay of horizontal lines, moving them into the adjoining spaces, to signify limitless interchange. Additionally the flow of the river meaningfully goes around the alcoves.

K.G. Subramanyan informs in his essay published in Benodebehari Mukherjee - A centenary retrospective, that “Benodebehari did not prepare any cartoon…but made numerous postcard size drawings… The technique of Fresco buono imposed the constraint of piecemeal work since it was not possible to work on more than two square feet within a day…It allowed him to rework structural components. Redrawing and the repeated layers of contours evolving from the rectifying process enhanced the density of the figures and pronounced their physicality. Thus in the absence of a pre- planned structure, the entire mural evolved in units measured by a day's work.”

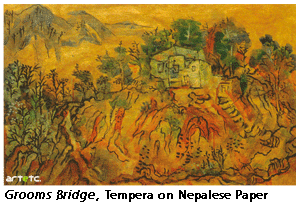

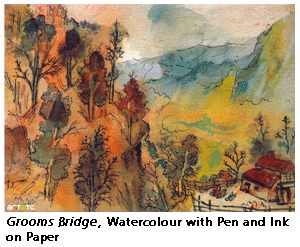

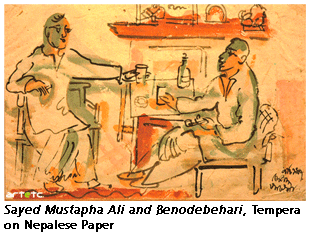

In the fifties, Benodebehari spent a number of years in Nepal where he did a large number of works on paper, in ink, watercolour, tempera, wash and ink. One noticed the minimalizing of the defining contours, masses of colour appeared to represent architectural elements, indicating space and its relationship with the positioning of figures. R. Siva Kumar in his essay, Benodebehari Mukherjee: Life , Context, Work, informs that – Life in Nepal was for him the opposite of life in Santiniketan, which was Spartan though rich in intellectual companionship …he became more openly responsive to the sensuous in life which came alive fused with an exotic charm in Nepal. And the absence of intellectual companionship was offset by educative encounters with accomplished artisans like Kulasundar Shilakarmi who made him realize that art could be lifted to a higher plane, even given individuality, through consummate skill or a total oneness with one's means and openness of mind. This brought an important change to his aesthetic outlook and approach to art.”

The works created in Nepal is further described by Prananb Ranjan Ray as he draws attention to the transformation in Benodebehari's work, he says, “The figures themselves had become substanceless forms without details. But typological social identities were never missing. Subject matter again comprised common people engaged in work and enjoying leisure, pilgrims and devotees in temples and ghats, albeit devoid of their exalted majesty. It was the simulation of the rhythm of life constructed on surface, the relentlessly unified common uneventful life's transformation into joyous paintings laced with pathos.”

Benodebehari's creative pursuit continued even after the loss of his eyesight. Pranabranjan Ray Mentions that “so unvanquished was his nurtured spirit that he would refuse to regard his unseeing eyes as organs for spiritual vision.” The artist created collages of figures with mass and arranged them on flat surfaces. He also made lithographs with squiggles of unbroken lines suggesting actions of people in their daily chores. Resultant of this practice with the marble paper collages and the lithographs; the mural on the wall of the Kala Bhavana canteen in glazed tile, came which R. Siva Kumar in his essay reflects upon a subtle integration of his past and present work as he writes “…this mural encourages us to read it with reference to our body and its movement.

Pranabranjan Ray in his conclusion of the essay evoke Rabindranath's vision of the Nation in harmony with its own array of regional and eventual cultural identities, a true reflection of the universe and its ways that again finds expression in Benodebehari's creative stance.

In this context Ray ruminates that “Unity in diversity has lost its meaning through political overuse and has become a cliché. But it was not so when Tagore had for the first time coined the phrase in one of his essays on Indian history, in the early twenties of the last century. More than a description of situation, it was a will that needed to be realized. Benodebehari's lifelong endeavour in art had been a celebration of the diversity with the aim of holding those in rhythmic unity. More than that, his was a grand endeavour of uniting art and reality-without compromising each other's sovereignty, in a symbolic relationship.”