- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Looking from the Other Side

- Women in Rabindranath Tagore's Paintings

- Ramkinkar Baij's Santhal Family

- The Birth of Freedom in Moments of Confinement

- Jamini Roy's Art in Retrospect

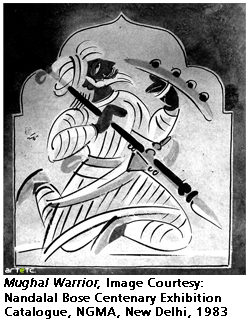

- The Great Journey of Shapes: Collages of Nandalal Bose

- Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

- The Post-1960s Scenario in the Art of Bengal

- Art Practice in and Around Kolkata

- Social Concern and Protest

- The Dangers of Deifications

- Gobardhan Ash: The Committed Artist of 1940-s

- Gopal Ghose

- Painting of Dharmanarayan Dasgupta: Social Critique through Fantasy and Satire

- Asit Mondal: Eloquence of Lines

- The Experiential and Aesthetic Works of Samindranath Majumdar

- Luke Jerram: Investigating the Acoustics of Architecture

- Miho Museum: A Structure Embedded in the Landscape

- Antique Victorian Silver

- Up to 78 Million American Dollars1 !

- Random Strokes

- Are We Looking At the Rise of Bengal

- Art Basel and the Questions it Threw Up

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, May – June 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Preview June, 2012 – July, 2012

- In the News, June 2012

ART news & views

Haripura Posters by Nandalal Bose: The Context and the Content

Issue No: 30 Month: 7 Year: 2012

by Soumik Nandy Majumdar

Elementary Concern

Nandalal Bose (1882-1966) had a natural flair for designing architectural constructs, interiors and stage settings for performances and ceremonies on various occasions and rituals in the campus of Santiniketan. He fostered the idea of 'art for the community' and 'collective art initiative' by setting innumerable examples, along with his associates and students, throughout his life. It is true that his innovative philosophy concerning art and art education within the larger context of social concern was influenced to a large extent by the ideas of two of his eminent contemporaries, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). While Tagore's focus was on the cultural regeneration of India, Gandhi's primary concern was the political and economic independence of our country. Inspired by both these personas and convinced by his own exposure and extensive field studies, Nandalal's spectrum of art-practice continuously and emphatically embraced the entire breadth of Indian art heritage, both living and past, with a strong prominence on the rural craft traditions. He upheld the significance of these traditions that were fast succumbing to the pressure of urban colonial culture. Like a true researcher he was extremely keen in his perception and understanding of handmade utensils, handmade toys and other household objects. He always paid tribute to the village potter and village artisan who fashioned his wares with simple tools and simple ideas.

Nandalal Bose (1882-1966) had a natural flair for designing architectural constructs, interiors and stage settings for performances and ceremonies on various occasions and rituals in the campus of Santiniketan. He fostered the idea of 'art for the community' and 'collective art initiative' by setting innumerable examples, along with his associates and students, throughout his life. It is true that his innovative philosophy concerning art and art education within the larger context of social concern was influenced to a large extent by the ideas of two of his eminent contemporaries, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). While Tagore's focus was on the cultural regeneration of India, Gandhi's primary concern was the political and economic independence of our country. Inspired by both these personas and convinced by his own exposure and extensive field studies, Nandalal's spectrum of art-practice continuously and emphatically embraced the entire breadth of Indian art heritage, both living and past, with a strong prominence on the rural craft traditions. He upheld the significance of these traditions that were fast succumbing to the pressure of urban colonial culture. Like a true researcher he was extremely keen in his perception and understanding of handmade utensils, handmade toys and other household objects. He always paid tribute to the village potter and village artisan who fashioned his wares with simple tools and simple ideas.

Elementary and even complex shapes arrived at effortlessly and somewhat intuitively by the master-craftsmen attracted his ever watchful and unerring eye. Be it a metal-ware, a wooden toy, or a potter's bowl Nandalal admired with great regards every product created by rural artisan-artists. In his childhood years, the artisans' workshops in his hometown of Kharagpur held an enticing attraction for him, and he often visited them and watched the woodworkers, metal smiths, scroll painters and others working with grace and a natural élan. “This fascination”, K. G. Subramanyan writes, “fed his desire to become an artist. … Even after he became a renowned artist and educator, he continued to see art and artisan practice as a connected panorama that ensured aesthetic creativity in a modem environment.”1

Nandalal keenly followed their methods and picked up certain technical nuances like a faithful disciple. He had observed that rural areas of India were adventurous in the use of colour on person, in textiles, in toys and in paintings. He clearly saw that the art which harnessed the vitality of folk art and rural simplicity could stand against the general rot ushered by a misconstrued industrial revolution. E. B. Havell and Ananda Coomaraswamy had already drawn attention to the indigenous craft conventions of our country and made it an imperative concern for the Swadeshi art. Historically speaking, the time was ripe for the crusade on behalf of indigenous craftsmanship and art. For all the variety of artistic explorations it is undeniable that Nandalal's faith in the rural culture was the kernel of his creativity. For instance, Khadi to Nandalal was not a mere coarse cloth made out of hand-spun yarn. It was full of infinite variations of textures born out of human sensibility. As Dinkar Kowshik writes, “Khadi (for Nandalal Bose) was an aesthetic equivalent of our will to work and our homage to the hands.” 2

Run-up to Haripura

For Gandhi, art and Nandalal were synonymous and he was proud and happy to have 'discovered' Nandalal as the artist of the Indian National Congress. On the other hand Nandalal too was witnessing how Gandhi strove to emancipate the country from colonial rule and soon became one of Gandhi's admirers. His respect for the Mahatma increased when his action program 'broadened its purview to include the economic independence of India and the strengthening of its widespread artisan traditions to achieve this.'3 Obviously, Gandhi's focus on India's artisan traditions had a special appeal for Nandalal. Nandalal's admiration for Gandhi is clearly evident in the famous lino-cut he did in the wake of Gandhi's historic Dandi march in March 1930. His war against the Salt-law that charged the entire nation was symbolized in a black-white lino-cut of modest size depicting Mahatma stepping out with his walking stick, evoking a sense of strong will to overcome all obstacles. That this image eventually became a visual prototype of the iconic image of Gandhi is now well known. Incidentally, Nandalal did not come to know Gandhi personally until 1935 when Gandhi sought Bose's help to install an art and craft exhibition at the Lucknow session of Congress in 1935. However, the first such exhibition to be organized in connection with a convention of the Indian National Congress took place at Indore in 1934. Gandhi recognized the importance of such exhibitions and believed that it should continue at all subsequent Congress sessions. Though Nandalal was initially apprehensive, he took it on his stride and despite severe paucity of funds got Benodebehari Mukherjee, Prabhat Mohan Bandopadhyay, Vinayak Masoji and Asit Kumar Haldar to assist him in this task. Nandalal and his associates undertook to arrange a historical panorama of Indian art including Copies of the Ajanta and Bagh murals, Jain paintings, paintings from Rajput and Mughal Schools, Kalighat Patas and works of Abanindranath and his disciples. While Nandalal was busy putting up all this together, Mhatre, an architect from Bombay supervised the construction including a novel gateway.

For Gandhi, art and Nandalal were synonymous and he was proud and happy to have 'discovered' Nandalal as the artist of the Indian National Congress. On the other hand Nandalal too was witnessing how Gandhi strove to emancipate the country from colonial rule and soon became one of Gandhi's admirers. His respect for the Mahatma increased when his action program 'broadened its purview to include the economic independence of India and the strengthening of its widespread artisan traditions to achieve this.'3 Obviously, Gandhi's focus on India's artisan traditions had a special appeal for Nandalal. Nandalal's admiration for Gandhi is clearly evident in the famous lino-cut he did in the wake of Gandhi's historic Dandi march in March 1930. His war against the Salt-law that charged the entire nation was symbolized in a black-white lino-cut of modest size depicting Mahatma stepping out with his walking stick, evoking a sense of strong will to overcome all obstacles. That this image eventually became a visual prototype of the iconic image of Gandhi is now well known. Incidentally, Nandalal did not come to know Gandhi personally until 1935 when Gandhi sought Bose's help to install an art and craft exhibition at the Lucknow session of Congress in 1935. However, the first such exhibition to be organized in connection with a convention of the Indian National Congress took place at Indore in 1934. Gandhi recognized the importance of such exhibitions and believed that it should continue at all subsequent Congress sessions. Though Nandalal was initially apprehensive, he took it on his stride and despite severe paucity of funds got Benodebehari Mukherjee, Prabhat Mohan Bandopadhyay, Vinayak Masoji and Asit Kumar Haldar to assist him in this task. Nandalal and his associates undertook to arrange a historical panorama of Indian art including Copies of the Ajanta and Bagh murals, Jain paintings, paintings from Rajput and Mughal Schools, Kalighat Patas and works of Abanindranath and his disciples. While Nandalal was busy putting up all this together, Mhatre, an architect from Bombay supervised the construction including a novel gateway.

Gandhi was greatly pleased with the austere aesthetics of the show and appreciated the simple bamboo, reed, and timber structures that housed the exhibits, as well as the straightforward mode of display. In his opening speech at this session Gandhi referred to the aesthetic arrangement that touched the base and urged the gathering to spend some time in appreciating the display and the labor that had gone into making it so successfully. In fact he announced that the exhibition he was going to declare open was the 'first of its kind'. He made everybody realize that village artisans from all over India were gathered, 'from Kashmir to South India, from Sindh to Assam' to make the display a memorable and learning experience. This on part of Gandhi was certainly a manifestation of his serious engagement with the issue which is further reflected in his nation-building activities, especially those related to economic independence. One such program was the All India Village Industries Association, which operated under the auspices of the Congress. In fact in a letter dated November 1934, Gandhi invited Tagore to lend his name to the advisory body of the All India Village Industries Association.

Gandhi was greatly pleased with the austere aesthetics of the show and appreciated the simple bamboo, reed, and timber structures that housed the exhibits, as well as the straightforward mode of display. In his opening speech at this session Gandhi referred to the aesthetic arrangement that touched the base and urged the gathering to spend some time in appreciating the display and the labor that had gone into making it so successfully. In fact he announced that the exhibition he was going to declare open was the 'first of its kind'. He made everybody realize that village artisans from all over India were gathered, 'from Kashmir to South India, from Sindh to Assam' to make the display a memorable and learning experience. This on part of Gandhi was certainly a manifestation of his serious engagement with the issue which is further reflected in his nation-building activities, especially those related to economic independence. One such program was the All India Village Industries Association, which operated under the auspices of the Congress. In fact in a letter dated November 1934, Gandhi invited Tagore to lend his name to the advisory body of the All India Village Industries Association.

The Faizpur session of the Congress followed almost on the heels of the Lucknow session and barely five months had elapsed Gandhi summoned Nandalal again hoping to put Nandalal's ability to the test in Faizpur where the next Indian National Congress session was to be held at the end of 1936. He wanted Nandalal to take charge of the entire work of the Faizpur meet. Nandalal intimidated by this many-sided assignment cautiously wrote back to say that he was just a painter, while much of the task was architectural. But Gandhi would not accept refusal. The artist later recalled that Gandhi wrote to encourage him with this cryptic message: "I do not want an expert pianist; I want a devoted fiddler." Subsequently the entire work in Tilak Nagar – near Faizpur was once again handled by Nandalal and Mhatre and they also received help from a group of young people who accompanied him from Santiniketan and the local artisans. For the Faizpur meeting, which was intended to be kept as free from urban influences as possible, Gandhi envisioned an entire township (Tilak Nagar in Central India) built with local materials – wood, bamboo, and hay – and wanted the exhibits primarily to be the handiwork of the local village artisans. The resulting exhibition and built environment exceeded all expectations, and Nandalal's resourceful use of simple local down-to-earth materials became a model for young designers in the years to come. In the main pandal where the exhibition was arranged, Nandalal had the ingenious idea of sprouting wheat seedlings around the central pole. When the exhibition was thrown open to the public, visitors saw a round oasis of live greenery in the middle of a graveled floor space. This novel way of beautification by pressing nature into a wonderful service received spontaneous admiration from all quarters.

The Faizpur session of the Congress followed almost on the heels of the Lucknow session and barely five months had elapsed Gandhi summoned Nandalal again hoping to put Nandalal's ability to the test in Faizpur where the next Indian National Congress session was to be held at the end of 1936. He wanted Nandalal to take charge of the entire work of the Faizpur meet. Nandalal intimidated by this many-sided assignment cautiously wrote back to say that he was just a painter, while much of the task was architectural. But Gandhi would not accept refusal. The artist later recalled that Gandhi wrote to encourage him with this cryptic message: "I do not want an expert pianist; I want a devoted fiddler." Subsequently the entire work in Tilak Nagar – near Faizpur was once again handled by Nandalal and Mhatre and they also received help from a group of young people who accompanied him from Santiniketan and the local artisans. For the Faizpur meeting, which was intended to be kept as free from urban influences as possible, Gandhi envisioned an entire township (Tilak Nagar in Central India) built with local materials – wood, bamboo, and hay – and wanted the exhibits primarily to be the handiwork of the local village artisans. The resulting exhibition and built environment exceeded all expectations, and Nandalal's resourceful use of simple local down-to-earth materials became a model for young designers in the years to come. In the main pandal where the exhibition was arranged, Nandalal had the ingenious idea of sprouting wheat seedlings around the central pole. When the exhibition was thrown open to the public, visitors saw a round oasis of live greenery in the middle of a graveled floor space. This novel way of beautification by pressing nature into a wonderful service received spontaneous admiration from all quarters.

Right from the opening day of the session Gandhi repeated his praise for Nandalal almost every day. As K. G. Subramanyan writes, “Before the Faizpur session, Nandalal's reputation as an artist had been confined primarily to the elite artistic community in Bengal (and elsewhere), but Gandhi's unstinting praise of his work brought him national fame: in essence, he became the artist laureate of nationalist India.” 4

Dinkar Kowshik reminds us that 'The work at these sessions was purely a labour of love, but to Nandalal it had a special attraction. It provided him with a site and material for trying out his novel experiments in art for the community. Gates, pandals, landscape gardening and posters for social education could be planned and executed. It was an opportunity for creating art with social relevance. Above all, he could be close to Mahatmaji, a privilege he would not have liked to miss.' 5

Haripura Posters

The next Congress session was to be at Haripura, near Bardoli in Gujarat in February of 1938. Once again Gandhi placed Nandalal in charge of creating a unique environment infused with local art and craft. And once again Nandalal pleaded his inability, partly because he was not keeping well and partly he was demoralized to hear that some local artists gave public expression to their parochial feelings as they were unhappy to have somebody from outside Gujarat. But within a week of his letter to Gandhi he turned up at the Bardoli camp to Gandhi's surprise and relief. Consequently Nandalal proceeded to Haripura and studied the site and surveyed the availability of local materials and craftsmanship. At Haripura, Nandalal turned the sprawling area into an exquisite example of environmental art. Gates, pillars, exhibition, cluster of stalls, thatched shelters, landscape garden, meeting areas and residential tents were all decorated with local material of bamboo, thatch and khadi of different hues. Earthen pots and vessels were adorned with designs; tassels of paddy grass hung in rows, baskets and cane work – made by the hands of local craftspeople – were all used to lend the session an elegant rural atmosphere. As a significant component of this huge public art Nandalal planned separate paintings which were later to become famous as Haripura posters depicting Indian life in all its variety.

The next Congress session was to be at Haripura, near Bardoli in Gujarat in February of 1938. Once again Gandhi placed Nandalal in charge of creating a unique environment infused with local art and craft. And once again Nandalal pleaded his inability, partly because he was not keeping well and partly he was demoralized to hear that some local artists gave public expression to their parochial feelings as they were unhappy to have somebody from outside Gujarat. But within a week of his letter to Gandhi he turned up at the Bardoli camp to Gandhi's surprise and relief. Consequently Nandalal proceeded to Haripura and studied the site and surveyed the availability of local materials and craftsmanship. At Haripura, Nandalal turned the sprawling area into an exquisite example of environmental art. Gates, pillars, exhibition, cluster of stalls, thatched shelters, landscape garden, meeting areas and residential tents were all decorated with local material of bamboo, thatch and khadi of different hues. Earthen pots and vessels were adorned with designs; tassels of paddy grass hung in rows, baskets and cane work – made by the hands of local craftspeople – were all used to lend the session an elegant rural atmosphere. As a significant component of this huge public art Nandalal planned separate paintings which were later to become famous as Haripura posters depicting Indian life in all its variety.

Reportedly, Nandalal painted nearly eighty posters himself, mostly about two feet by two feet large in size, and his student and teacher associates then made close copies of them, multiplying their number to close to 400. Created on handmade papers stretched on strawboard, these paintings or posters were executed with brilliant colors prepared and mixed from the local earth pigments. Bamboo, thatch, and homespun cotton were employed to construct the display panels all around. Gandhi wanted the posters to catch the attention of passersby, so they were displayed at the meeting compound's main gate and on the exterior of the pavilions. One can imagine that the whole vista turned out to be a public art of a huge hitherto unseen scale. Nandalal Bose himself writes with enthusiasm, 'Following the pata style we did a large number of paintings and hung them everywhere on the main entrance, inside the volunteers camps, even in the rooms meant for Bapuji and Subhasbabu, the President.' 6

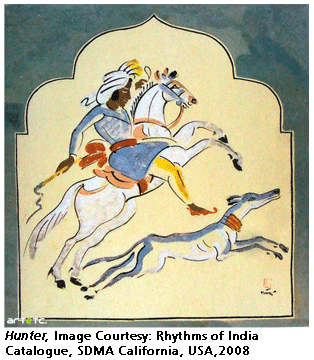

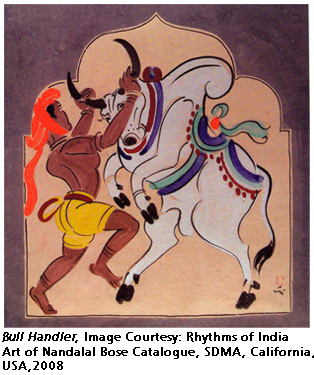

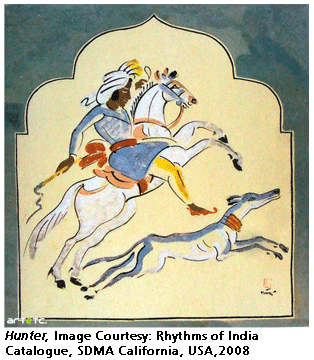

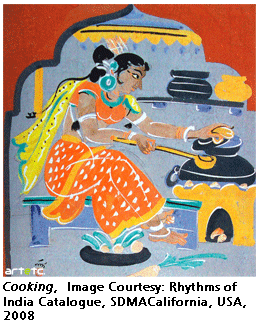

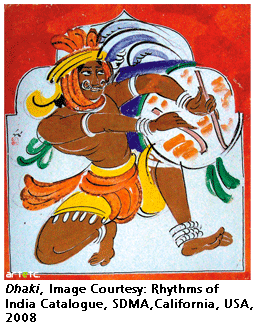

Haripura posters celebrate the Indian rural life and culture sharing a vibrant earthy color palette and bold, energetic lines with a vividly modernist graphic quality. A sweeping look at the available images reveals that these posters draw attention to the different activities, professions and trades that constellate the moments of village daily life in a picturesque continuum. Most of the imageries culled from his observed reality around were developed from the rapid sketches Nandalal did during his survey of rural areas and people living near the location. The swift, spontaneous strokes contouring the forms and figures encourage an equally effortless viewing reminiscent of the character and temperament of Kalighat pata and various other folk paintings that eschew any labored or affected idiom. The charm and the playful gaiety exuded by the linguistic features blend perfectly well with the contents depicting subjects like Hunters, Musicians, Bull Handlers, Carpenter, Smiths, Spinner, Husking women and modest scenes of rural life including animal rearing, child-nursing and cooking. The simplicity of these works also lies in the unvarying use of the point-cusped niche that frames the principal subject. The vigorous dynamic forms of certain figures of course cut across the frame thus saving the images from monotony.

According to Binodebehari Mukhopadhyaya, “In these Haripura panels painted for the session, there is an ineluctable harmony of tradition and study based on observation. Each poster is different from the next in form as well as in colour and yet there runs all through a strong undercurrent of emotional unity, lending a familial stamp. The artist has not looked towards any ideals either traditional or modem, but keeping an eye on the contemporary situation, has worked out his own goal. The stream of form and colour which flows over the subject, subordinating it, brings these posters into kinship with mural art.” 7

Considered to be his greatest contribution to the popular culture of mass nationalism, Haripura paintings brought Nandalal accolades and widespread recognition. Through these paintings, in a certain sense he came close to Gandhi's purported mission 'to make Gods out of men of clay'.

Reference

1. K. G. Subramanyan, 'The Nandalal Gandhi Rabindranath Connection', Rhythms of India, The Art of Nandalal Bose, (San Diego Museum of Art, California, 2008) p.92

2. Dinkar Kowshik, 'Nandalal Bose, the doyen of Indian art' (National Book Trust, India, 1985) p. 37

3. K. G. Subramanyan, op.cit., p. 92

4. K. G. Subramanyan, op.cit., p. 99

5. Dinkar Kowshik, op.cit., p.49

6. Nandalal Bose, Vision and Creation, (Visva Bharati, 1999) p.235

7. Dinkar Kowshik, op.cit., p.50