- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

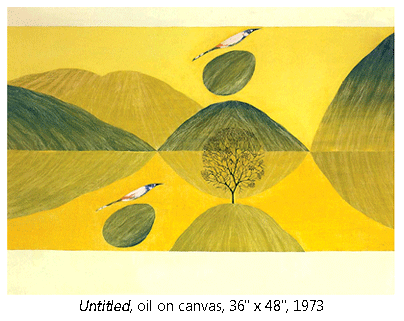

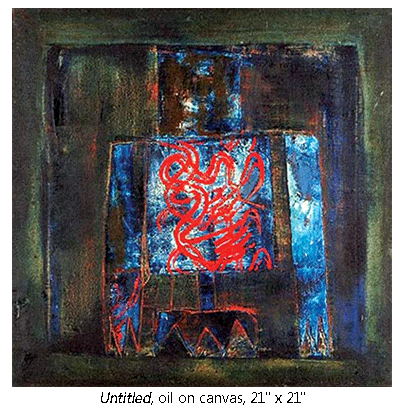

A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

by Vinod Bharadwaj

Jagdish Swaminathan is among India's foremost modern artists. He claims to work in the spirit of a man possessed. He is among those artists who are also able to express themselves with ease in words. Holding a conversation with Swaminathan is a revealing and intellectually stimulating experience.

Vinod Bharadwaj: Tell me something about your creative process when and how do you like to work?

Jagdish Swaminathan: There was a time when I would work till late into the night. But it's not easy to work with colours at night, yellow in particular. Moreover, the time of work is related to a painting arriving at a point where it would progress on its own. Initially I liked to go for impasto with thick colours - I would use the palette-knife quite a lot, which I no longer do. The application of colour has become quite 'fine'.

VB: What kind of inspiration do you need for painting?

JS: I can find solace even without having done anything at all in the manner of speaking. The most difficult part is starting on a work... But once I start then it is a different matter.

VB: What do you consider as central to your growth as an artist?

JS: I feel I am not one of those artists whose work is totally free of any intellectual dimension. I am more concerned with having an emotional perspective in relation to the intellect. Not that I have an intellectual perspective on emotions. All that I am saying is that intellectualism has a place for me in explaining things.

VB: Do you like to talk about your work or do you believe a work should speak for itself?

JS: I am yet to meet an artist who would not like to talk about his works. All of them claim they wouldn't say anything whereas other than that they talk little. To understand a painting an explanatory comment is not necessary. The ideal situation would be that you see a painting and receive from it what you can. But artists are quite vocal about their art.

VB: What special elements do you notice in the contemporary art landscape?

JS: The contemporary art movements have thrown up quite a few superficial points of view. The depth which the artists of the Progressive Group possessed is no longer to be found... Some of the Indian artists have undergone a transformation. For example before his arrival in Europe Tyeb Mehta, in the manner of Progressive artists, would use 'brush stroke' and palette-knife to create the core image. But he gave up this practice on his return to India and flat colour surfaces came to be seen in his works which were completely devoid of any brush-stroke or palette-knife. I have this feeling that he has distanced himself from the modern western tradition, for which nearly all the Progressive Group artists had fallen... Earlier, the entire burden was on managing the brush and the palette-knife. Now there is freedom from this compulsion... It's not a matter of Indian art or Western art. Had we continued to follow the tradition, nothing would have been possible. Total rebellion alone has brought about results. The truth does not lie in slogans, though here I remember that famous artist Miro. Surrealist artists were moving ahead shouting against the French state: 'Down with the government'. But Miro had a different slogan: 'Down with the Mediterranean'. Because that's where everyone had one's roots. Everything that predated it got erased.

VB: Taking into account the acute difference between the Western and Indian art, many critics take you as a hardcore opponent of the West. How do you react?

JS: There is nothing like West or East confronting today's artist. But the influential tradition is the western tradition and one has to have doubts about it. At least I do. Our artists are emerging from a background crowded with a diversity of stories, opinions and philosophical viewpoints. The basic question is whether one needs to be aware of them or not. The philosophy that there's only the colour and the canvas and nothing more is not right. Most of our philosophical theories are based on Indo-Anglican interpretations. It is this perspective which has given us faith in Ajanta, Mughal miniatures etc. At a London exhibition of modern artists like Husain, Ramkumar, Gaitonde and others, an 'intellectual' present there had introduced them stating that they were the very modern artists of India promoting western awareness in their country... In the West the tradition of the modern man is a dying tradition. There, the modern art passed through the self-oriented consciousness of Modigliani and moved towards what was completely object-oriented... I count the Western civilisation as dying, not the Western man. Many thinking souls out there are against their own civilisation.

VB: What do you have to say about the fitful attempts in India to make a 'superstar' out of a modern artist on the strength of money and glamour?

JS: Most of the artists are quite shrewd. But this opinion need not be extended to their art... When the economy in a society is driven by market forces then every man has to put up a constant fight... I am not suggesting that this is all right. There must be artists out there who are beyond such material concerns but most of them introduce themselves quite aggressively... But a majority of them is alert to market forces. It would be a misguided belief to expect that an artist could change the whole society within his lifetime. In that case he should give up his work and devote himself solely to bringing about social transformation. Other than the marketplace where else does the artist have a dialogue with society? The easel and the painting will remain an artist's personal property and not the people's and that's the truth.

VB: Only a narrow class of viewers is interested in your art. Do you sometimes get depressed by this?

JS: The fewer the viewers the better. Two, four, ten... I don't look out for too many of them. Even if one of them is able to find what he may be looking for...

VB: Birds, mountains etc. are the familiar faces of your work today. Do they signify repetitiousness? As an artist what is your level of awareness about this tendency?

JS: In the last 18 years my art has passed through five well-defined phases which is quite a lot. What happens is that when you see a recognisable object, and notice it time and again, then you come to 'feel' it's repetition. . Either you are doing less or doing more; nothing is the same every time. The artists who continue to alter their narrative or subject-objects, even in their case the colour scheme and the range remain the same. On seeing one of my paintings you cannot say with certainty that it's Swaminathan's line. I do not have a particularly special way of drawing a bird. In my art the 'form' does not originate with a point. That is there as if already in place. That's why when Geeta Kapur compares me with Paul Klee, it's not the right comparison. I regard Klee highly. But I never followed Klee's artistic aims. In Klee's art and in the development of his line there's a rhythm, whereas for me the line already exists.

VB: Among your early experiences what is it that you consider important in your development as an artist?

JS: In my childhood, while at school, I had only two passions Hindi poetry and painting... In the final years of my school and the early years of my college days I wrote a large number of songs.

VB: What is it in particular among your early days which you find significant?

JS: Difficult to say. I had very strong romantic inclinations within me. I kept Jigar [Moradabadi] Saheb in high esteem. I even set out to write his biography... My father was in the government service. The life was at the level of a babu. I was quite attracted by this contrast. Like a devotee totally given over to the worship of god, he would completely immerse himself in the world of poesy.

VB: You tend to devote a lot of time to the Akademi. Don't you feel inconvenienced?

JS: I do feel a lot of inconvenience. But I take up such assignments prompted by a sense of social responsibility. Sometimes I feel defeated as well... But it's also in my nature to struggle so as to have my say as well as my space. Many leading artists, who feel disillusioned after long years of association with the Akademi, might change their opinion if the circumstances again become favourable. During the last Trienniale the late Rosenberg had said that this kind of work was essential the struggle to get approval for a movement whereas Morris Graves... was so scared on seeing the burgeoning crowds of Calcutta that he was driven to return to America. But we are surviving in this situation.

This interview was originally published in Ravivar (1979), in Hindi which was a newsweekly by Anandbazar Group