- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

Feature

by Nanak Ganguly

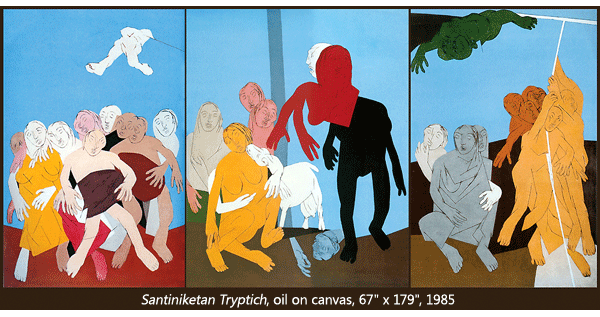

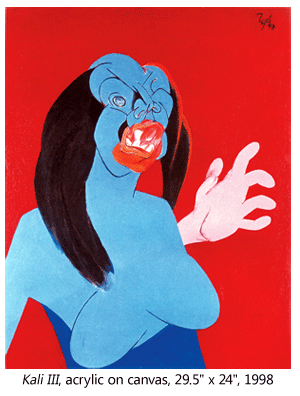

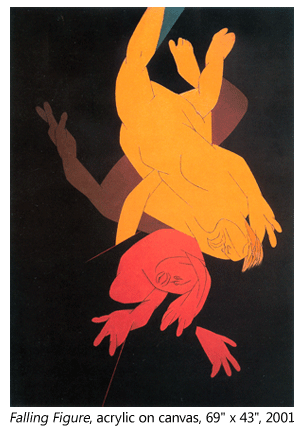

Tyeb Mehta (1925-2009) was not concerned with the problem between relations in the painted space rather with the active and neutral elements amidst opposite markers. His idea in his falling figures was to define an opposition and control the tension in his painting through space, matrices, images and colour to bring out a crisis, established by a gesture and holding such elements on check. The isolation of the figure, the violent deformations of the flesh, the complex use of colour, the method of chance for example his Kali image, and the use of triptych form (Santiniketan, oil, 1985). It was born from another struggle within the self while decided to abjure from the narrative exuding a suffocation and angst. Since the purpose of imagery is to remind us, by approximation, of those meanings for which the image stands, and since, apart from this, imagery is unnecessary for thought, we must be more familiar with the image than with which it clarifies. There is another element in Tyeb's paintings- the large fields of colour on which the figure detaches itself, fields without depth or with only the kind of shallow depth and taunting acrobatics. The paintings consist of a visual hold, an immediacy and enigmatic gripping presence. “I think there are many levels of violence one goes through as a human being…between me and the image, the image itself and its own connotation, and the way I structure the painting, there is so much mutation that when it reaches the viewer, it has another power totally.”(Tyeb Mehta In conversation with Yashodhara Dalmia).

There is another element in Tyeb's paintings- the large fields of colour on which the figure detaches itself, fields without depth or with only the kind of shallow depth and taunting acrobatics. The paintings consist of a visual hold, an immediacy and enigmatic gripping presence. “I think there are many levels of violence one goes through as a human being…between me and the image, the image itself and its own connotation, and the way I structure the painting, there is so much mutation that when it reaches the viewer, it has another power totally.”(Tyeb Mehta In conversation with Yashodhara Dalmia).

He was born in 1925 in Gujarat and grew up and was educated in Bombay. After school he even considered a career in films as his family had strong business connections with the Hindi film industry. But he joined JJ School of Art, instead in 1947 and graduated five years later, setting aside his first love cinema, to be regarded as one of the most radical painters of our time. Fraught and frazzled is what it does not only reveal but provides instead a wholly indigenous renewal of “self”, his text attempts to set up a dialogue between our obsessions and private associations. His text can be read as an allegory of the artist's calling. To follow through his entire body of work is to live with him through the discoveries, the concerns, the anxieties, the influences, the empathies, and the pursuits of his long and intense life. For him life was not inseparable from art. “He was devoted to his work day in and day out'' reminisces Akbar Padamsee. The interchanges closely related between painting, sculptures, cinema and his associations, between colour and form, between reality and illusion, between irony and tragedy appeared with surprising agility- a proof of his extraordinary talent, intellect and the coherence of his thought interspersed with a continuous stream of idea, creativity and image. But what concerns here is this absolute proximity, this co-precision, of the field that functions as a ground, and the figure that functions as a form, on a single plane that is viewed in close range proceeded with the somber, the dark, or the indistinct. He consciously lived in his times and wished to engage with events rather than withdrawn from them, the times fraught with new as well as abiding traumas. The non-violence is a distant phantom, an empty social pantomime, probably? In fact the violence, mutilated figures provide rich insights into the ways one of our leading painters interpreted and related to our political history, central keywords in politics of our daily life, pogroms in the country in the decades following the Independence. He obtained that blurriness by the techniques of free marks or scrubbing both of which are also among the precise elements of the system. He depicted them with extreme sensitivity.  Even in his short film Koodal (1969-70), the slaughtering of the bull is a mirror image of the slashed canvas and its many limbed figure, a metaphor. These are powerful symbolizations of the Partition in 1947.

Even in his short film Koodal (1969-70), the slaughtering of the bull is a mirror image of the slashed canvas and its many limbed figure, a metaphor. These are powerful symbolizations of the Partition in 1947.

In those fractured times, an entire generation of restless, feisty youth came into their own heroic attempt to find a voice. Until then we were still predisposed, if residually, to single parent relationship with the “nation” particularly in that period of reinvention since the culturally defining moments of the 50s and more prominently the 60's have come increasingly to embrace the dual realities of post-war, post-famine multi- cultural immigration and of their subcontinent context, resulting in a consequent revitalization of cultural priorities and objectives.

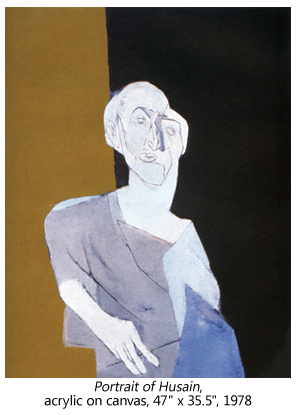

In an interview to Yashodhara Dalmia he once said, “No one knew anything. In 1947/48/49 even the members of the Progressive Artist's Group didn't know a damn thing about painting. Now its history and it seems to be impressive. But there was a lot of enthusiasm, tremendous passion, a desire to know things about art. We used to meet every evening at the Bombay Art Society or at Chetana or at Raza's Raja Ram Studio at a given time, Bombay had those ten to fifteen people who were concerned with painting. When I joined the JJ School of Art, to my good fortune Mr Palsikar also joined as a teacher. He was very enthusiastic about teaching. We used to spend our holidays at his place. The first book on modern art, a book by Kandinsky was given to me by him. It indirectly made me a big difference. Akbar's (Padamsee) elder brother, Nurrudin, would talk a great deal about art and literature. He was a very well read man. Even Sham Lal's 'Life and Letters, the presence of Ebrahim Alkazi' in Theatre Unit, all these people made the atmosphere very charged.  To see Husain in 1940/50 give up his job to paint pictures, with his children living in a small room gave us a lot of courage. There was a great guy called Pratap Singh who was one year senior to me. He used to recite poetry, especially Krishna Leela in Brajbhasa. Later he went away to look after his zamindari. Those were great times. We were all developing together in different directions. ….Akbar went to Paris in 1951 and lived and worked there for many years. I lived and worked in London for five years….I was connected to the Progressive Artist's Group from the outside, never as a member.”

To see Husain in 1940/50 give up his job to paint pictures, with his children living in a small room gave us a lot of courage. There was a great guy called Pratap Singh who was one year senior to me. He used to recite poetry, especially Krishna Leela in Brajbhasa. Later he went away to look after his zamindari. Those were great times. We were all developing together in different directions. ….Akbar went to Paris in 1951 and lived and worked there for many years. I lived and worked in London for five years….I was connected to the Progressive Artist's Group from the outside, never as a member.”

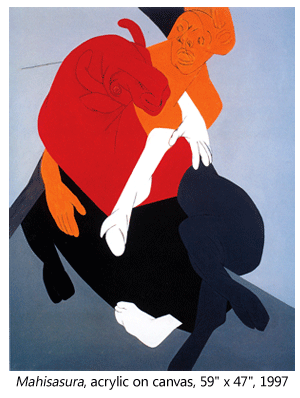

Tyeb's oil painting seems to present us with an essential painting. Mahishashura who has an unusual birth. Rambha, the demon king through an union with a she- buffalo begets a son. Tracing back various mythological sources Mahisha's unique lineage includes the divine, the exalted status of royalty and saint (rishi), the demonic and the bestial. Durga vanquishes him in a 10,000 year war. The myth carries the load of regeneration and revitalizing human and cosmic orders- an unending cycle of life, and the austerity of its black, white and gray tonal range that all the elements despite their values and divisions, mysteriously occupy a single plane and share the surface with graceful equality- their tonalities pushing and pulling and overlapping in space. But to stand in front of the painting is to experience the resolution of all these elements that gather into evenness that absorbs the areas of divisions into a unitary whole. The other part of the oeuvre is in his extraordinarily sensitive modulation of tints and shades. After having reduced his colour to no more than a scale of values, he pursues tonal painting with fervour and discipline valourizing the activities of his mind, evaluating, weighing and balancing the relative strengths of all that it encounters in its search for order and the unresolved complexities.

The erased areas between them have taken on a new resonance that pushes us to the figurative markers like his Kali. The salient elements are all held in tension on the same plane, with no element appearing to overlap or underline the other. This gives the paintings that quality of a world whose contents might be said to be suspended in a simultaneous presentness of being. In any case Tyeb did not hide the fact that these techniques are rather rudimentary, despite the subtlety of their combination. The important point is that they do not consign the figure to immobility but, on the contrary, render a sensible kind of progression, an exploration of the figure to its isolating place defines a fact, the fact is what takes place is thus isolate, and the Figure becomes an image, an Icon. A scream that culminates from lush amalgamations of restless lines that seduce atmospheric fields and framing edges to define a somewhat unreal space that is temporarily free from inane strictures. In these works, where images have the opportunity to displace objects, and the chance to hold reality at bay, paintings waste no time in pushing these freedoms their limits to a level of hysteria, a scream. In grandly scaled paintings whose richly textured surfaces are traversed by a single, unending line, this essential element in painting's repertoire of forms never extends beyond the edges of the picture plane but constantly double backs upon itself, curves around its sensual contours, and races back to its invisible point of origin where the swift visual movement begins it trace again in drawings and paintings.  Tyeb was a great painter who for once recapitulated the history of painting in an eclectic manner. The recapitulation consists of stopping points and passages, which reflect the horror of a riot victim or the despair of the marginalized. The language contains an affinity. “Many writers display a lazy and careless predisposition towards comparing superficial similarities between artists without reference to their individual and cultural contexts; in doing so they invariably mistake affinity for identity. Much has been made for instance, of Tyeb's supposed debt to Francis Bacon. There is, indisputably, a formal affinity between the two, in terms of figurative choices, compositional structure and implied atmosphere.”(- Ranjit Hoskote, Images of Transcendence: Towards a New Reading of Tyeb Mehta's Art. Ideas Images Exchanges, Vadehra Art Gallery, 2005). “I have a great respect for Bacon's work” he once said. “At this moment I felt a compulsion to borrow his figure study in 1972. When painter paints, inspired by someone else's work, he executes it according to his vision. What I am doing is, I am actually more or less reproducing Bacon's image and juxtaposing it with my own. I want to see if it can hold.”

Tyeb was a great painter who for once recapitulated the history of painting in an eclectic manner. The recapitulation consists of stopping points and passages, which reflect the horror of a riot victim or the despair of the marginalized. The language contains an affinity. “Many writers display a lazy and careless predisposition towards comparing superficial similarities between artists without reference to their individual and cultural contexts; in doing so they invariably mistake affinity for identity. Much has been made for instance, of Tyeb's supposed debt to Francis Bacon. There is, indisputably, a formal affinity between the two, in terms of figurative choices, compositional structure and implied atmosphere.”(- Ranjit Hoskote, Images of Transcendence: Towards a New Reading of Tyeb Mehta's Art. Ideas Images Exchanges, Vadehra Art Gallery, 2005). “I have a great respect for Bacon's work” he once said. “At this moment I felt a compulsion to borrow his figure study in 1972. When painter paints, inspired by someone else's work, he executes it according to his vision. What I am doing is, I am actually more or less reproducing Bacon's image and juxtaposing it with my own. I want to see if it can hold.”

Taking into account the complex manipulation of space in his works- large areas of a flat delineation of pigment act as a catalyst to the simplification of techniques to a form of shock and disquiet. Noted cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote writes “Standing before these often monumental scale frames, we bear helpless witness to the predicaments into which the artist knits his singular, isolated protagonists”. The viewer strays into them as if in half remembrance, unanchored on to the textures in a vast middle of broken vectors; the substance of a wakeful nightmare materializing image and reality, dream and component made by flat paint and beguiling the viewer into a seemingly no-win game of illusion and recognition of many beginnings and no end. Despite his direct address of violence and immediacy of marking of terror, an accumulating, linear density is reminiscent of the anxious scrawls that seem to be both forming and yet so tormenting and eating away at the withdrawn figures in our pre-modern drawings churn with the rain, stream and speed whose forms are emerging and dissolving in mist and light and dynamism that constitute an internal landscape which is the source of an extraordinary vitality. When Tyeb distinguished between two violences, that of the spectacle and that of the sensation, and declares that the first must be renounced to reach the second, it is kind of declaration for faith in life.

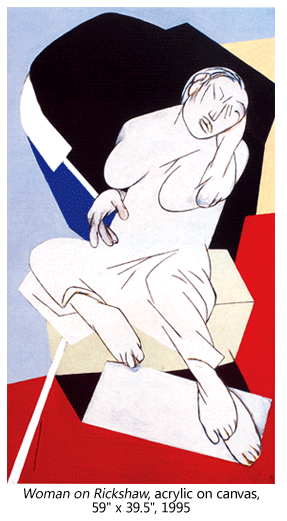

Tyeb's work reinforces our impression of a veiled narrative- the story of contained terror goes more subjective. To conjure up experience through the shape and weight of lines and rhythms of his earlier drawings are eloquent. Other oppositions as different it may be from an external tactile mould, modeling in chiaroscuro acts like a mould that has been internalized, in which the light penetrates the mass unequally. “Violence anguish, terror; each painting becomes an attempt to come to terms with this trio. The rigorous attention paid to formal values is a discipline helping to shear off sentimental indulgence in their themes. In retrospect, the shift from the expressionistic brushwork of the earlier paintings to the cooler language serves the same function. It is painterly yoga, employed to contain terror…..Kali is Mehta's own personal tormentor, in disguise. But she bides her time, and consents to appear in her own form only when the painter has acquired stature enough to be able to step out of the confusions of his own torment.  He can give us an icon that has moved from the area of the personal and existential, to shared public domain; an astonishing image that is both ancient, and truly contemporary”. (- Gieve Patel. Fifty Years of Indian Art, NCPA conference, 1997). The entire repertoire has a nervous, inchoate quality, as figures, both wraiths like and robust, take on symbolic weight as they get filtered through liquid swells and flows of translucent strokes. It is a long line of flight in those trussed bulls, the rickshaw puller (culled from his childhood memories, spent with his maternal grandmother in Calcutta during summers) and falling figures in which the delineation creates traces of the real and composing. In his triptych “Santiniketan”, the element which was once provided by iconography now springs largely out of his expressive handling where one discovers rhythm as the essence of painting. For this is never a matter of this or that character, this or that possesses rhythm. On the contrary, rhythms and rhythms alone become characters- the figure.

He can give us an icon that has moved from the area of the personal and existential, to shared public domain; an astonishing image that is both ancient, and truly contemporary”. (- Gieve Patel. Fifty Years of Indian Art, NCPA conference, 1997). The entire repertoire has a nervous, inchoate quality, as figures, both wraiths like and robust, take on symbolic weight as they get filtered through liquid swells and flows of translucent strokes. It is a long line of flight in those trussed bulls, the rickshaw puller (culled from his childhood memories, spent with his maternal grandmother in Calcutta during summers) and falling figures in which the delineation creates traces of the real and composing. In his triptych “Santiniketan”, the element which was once provided by iconography now springs largely out of his expressive handling where one discovers rhythm as the essence of painting. For this is never a matter of this or that character, this or that possesses rhythm. On the contrary, rhythms and rhythms alone become characters- the figure.

This painted ground, this rhythmic unity of senses, can be discovered only by going beyond the organism. Something of the same quality is transmitted- an oddness, a disturbing quiet- a gasp of death. One discovers in Tyeb's language an attempt to eliminate every spectator, and consequently every spectacle deepens resulting in a strong affinity towards the unraveling of the subliminal presence in a form. This should not be confused with the visible spectacle before which one screams, nor even with the perceptible and sensible objects whose action decomposes our pain. It becomes interesting at this point how these introspective elements interact with the existing play with form and the resultant stylistics hold on to that tenuous thread beyond pain and feeling that connects its operations to those of the world, whose appearances, at least are conspicuously absent from their frames. The small vessels seek to break out of “the purified domain of light and colour” that he established. We can certainly think painting, but one can also paint thought, including the exhilarating and violent form of thought that is painting.