- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

by Ella Datta

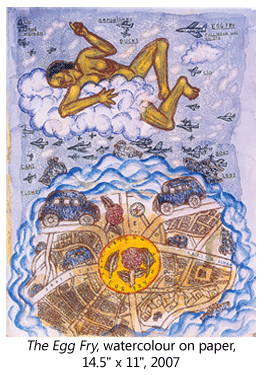

In the fifty years of her career, New Delhi artist Arpita Singh's language has acquired a distinctive edge. Make-believe water-lilies in lush pink, dark grey toy cars, paper boats, birds/planes in the sky and plump oranges, share space with skeletal remains, gun-toting soldiers and drowning men brandishing swords. The beautiful and the bizarre, the divine and the demonic co-exist on the canvas. The beautiful and the macabre are blended in such a way that it makes a profound impact. With her evolvement as an artist, she has overcome the challenges of the picture space and dexterously, yet playfully, fused reality and fantasy creating a unique idiom that is at once child-like, naive, and yet highly sophisticated in its basic idea and emotional quotient.

Her sensibilities, which shaped her images, have been tinged with her childhood memories of loss, dislocation and journeys. Meanwhile the poignancy of her youth slipping away has triggered another rising tide of melancholy. It is not surprising that death is a recurrent motif in her paintings. A pronounced note of melancholy pervades many of her watercolours. In the suite of watercolours, this strain of sadness intensifies into a sense of menace. Yet her paintings seem to be able to negotiate the acute sense of loss that is layered within her being, as an artist, and the reality that she experienced.

Meanwhile the poignancy of her youth slipping away has triggered another rising tide of melancholy. It is not surprising that death is a recurrent motif in her paintings. A pronounced note of melancholy pervades many of her watercolours. In the suite of watercolours, this strain of sadness intensifies into a sense of menace. Yet her paintings seem to be able to negotiate the acute sense of loss that is layered within her being, as an artist, and the reality that she experienced.

As Arpita grew both as an artist and as a person, the reality of the larger world, its history and geography, began invading the play world of her picture space. Her dream-time had to make space for real time which then elided into imagined times of the past and the future.

There is a psychological and a political merge in the paintings of Arpita Singh. So do everyday life and allegory, expressionism and ornament, historical sources from Bengal folk painting to Marc Chagall, and a formal approach that is at once unassuming and hard-worked, gauche and poised. These observations distill the essence of Arpita's images we see increasingly events in the public sphere triggering her imagery and the violence witnessed in society finding expression in her canvases.

The names of objects and forms that she was painting are like clues pointing to some unknown, elusive truth that are nudging at Arpita's subconscious, demanding attention and acknowledgement. It is also as if the words will aid the visuals to conjure up a reality that exists in the artist's mind. There is no permanence in Arpita's process of selection and dismissal.

In a conversation with painter Nilima Sheikh Arpita once said, "Motifs are negotiable, so circulate easily. I picked up the spine I use in my paintings these days from Nalini's (Malani) of a few years ago, reminded of it when I saw a film on her recently.  But then it may have already been in my mind because of Frida Kahlo." This comment gives an idea of the circuitous route through which the glimmer of a concept moves before it becomes a part of an artist's vocabulary.

But then it may have already been in my mind because of Frida Kahlo." This comment gives an idea of the circuitous route through which the glimmer of a concept moves before it becomes a part of an artist's vocabulary.

Roads and road maps are familiar metaphors in her works. She began with mapping neighborhoods, and then charted cities, moving on to representing a meta reality where past, present and future, reality and fantasy, the conscious and the liminal subconscious ambiguously shared the same spatial reality. Just as she became fascinated by outer space, she was also attracted by what lay below the surface, the archaeology of material cultures. One of the watercolours called Once Again it is Time to Take Flight showed a group of primitive men moving from one location to the other. Above them in the sky are a flock of migratory birds. Her personal movements from one location to another are subsumed into her overwhelming interest in migrations and journeys from prehistoric times.

Again the ageing female body emerged as one of the telling metaphors of the poignancy of the passage of time her sense of irony and the mysterious subliminal drives that go into the construct of an image. Arpita's rendering of fabrics, their creases and folds, the warp and weft of a weave, the serried stitches that a needle makes on cloth, even the floral frames point to the artist's enduring engagement with, even passion for, the textile traditions of India. Textile and fabric designs have left a deep impression on her painting. These designs play a critical role in the warm, colourful play-world that she creates on her canvas. She handled colours with a dazzling virtuosity, juxtaposing them with a startling assurance.

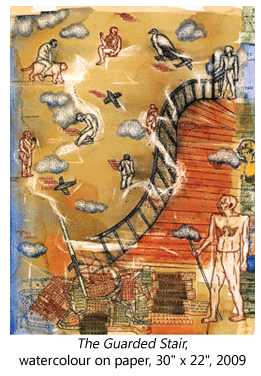

One of the new motifs that she has introduced in her recent suite of paintings is the architectural element, stairs. The idea of using stairs as a form came to her tangentially when she noticed a reflection, the fragment of a design created by light and shadows, on the wall of her previous home.  She made a sketch of it and the form is being used both as a metaphor of a journey into the unknown as in The Guarded Stair or to create an intense, almost claustrophobic ambience in Steps and Corridors, a watercolour.

She made a sketch of it and the form is being used both as a metaphor of a journey into the unknown as in The Guarded Stair or to create an intense, almost claustrophobic ambience in Steps and Corridors, a watercolour.

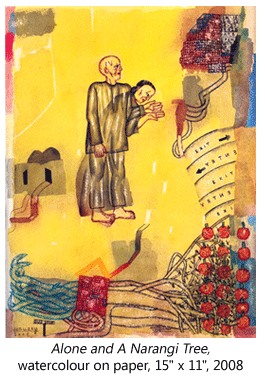

Locations are also very important in her work. The watercolour Alone and a Narangi Tree shows the Chinese orange tree in the garden of her new house. The details featured in the work capture the landscape of her neighborhood. She is also drawn towards recording gestures; the way people sit, stand, and engage in daily activities.

Arpita has always done drawings and sketches to give form to her nascent ideas. The sketches shorn of the magic of colour and texture are very compelling because they give a glimpse of the tensile strength of her lines and structures. This is also why her monochromatic drawings are important. They reveal her strong control over lines and tones and show one of the significant elements that distinguishes her as a master. They also hint at the direction her images are taking. Often the sketches provide clues to the simplifications and transformations that occur in Arpita's doodling in her notebooks.

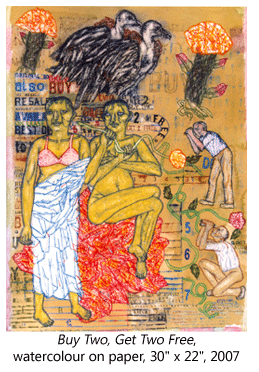

Following her experiments with abstract drawings in the seventies of the last century, Arpita explored the possibility effusing the abstract grid-like elements in her figurative work, particularly as backgrounds. While Arpita does not like relating her paintings to any single incident, one cannot help wondering whether the violent climate of our times does not leave a mark on her memory. Aggression, she seems to say, is embedded in the human psyche from the remembered beginnings of time. It has travelled down complex courses to colonize the instincts of modern man. Not all her paintings, however, carry undertones of seething violence. Arpita gives expression to the playful fantasy inherent in her character in the watercolour titled The Egg Fry. In the watercolour, Buy Two, Get Two Free,  Arpita introduces an ironic take on the rampant commercialism of our times.

Arpita introduces an ironic take on the rampant commercialism of our times.

Arpita's watercolours have a very distinctive place in the course of Indian watercolour painting. First of all, despite the inherent transparency of the medium, Arpita achieves a saturation of colours which is worth special note; then, there is the unusual treatment of the surface. Whether it is oil, watercolour or drawing, Arpita is very conscious about the surface of her work. In watercolours, Arpita has devised an intricate process where she applies layer upon layer of pigment on thick paper, rubbing them repeatedly with fine sandpaper and then building up the scraped surface with paint and enjoying the textures that she creates. Through it all, her brush laden with paint flows sensitively over the paper in a complex play of light, colour, lines and texture.

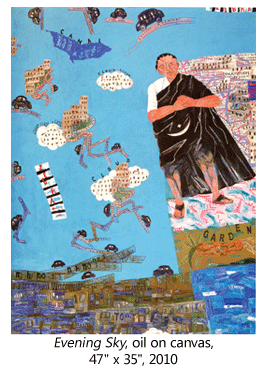

There is a distinctive rhythm, a pattern in Arpita's works. First, she makes a drawing or a sketch to work out a visual idea. Then the idea may be worked out in a watercolour or in oil which may later be incorporated in the large painting. There are often personal references in her work - reflections of journeys she has taken, astral configurations that have impressed her, representations of flowers or fruits whose forms have interested her, echoes of news items or signages that have left a deep impress. The oil painting titled Evening Sky, captures visually her experience of watching from her garden the glittering planet Venus poised over a shining moon. This painting is also an excellent example of how Arpita handles the inside/ outside dialectic in her work.

Arpita, like many other artists, transferred her immediate distress, experienced during a turbulent time around her, into a scene from archetypal history. Many creative artists resort to transferring their narrative into a mythic event. The enormous scale and intensity of an emotional experience generated by things happening in the public domain finds the right kind of resonance in the events narrated in the age-old, larger-than-life epics. Communication becomes simpler through them,  as the magnitudes of the epic's events are already deeply imprinted in popular imagination.

as the magnitudes of the epic's events are already deeply imprinted in popular imagination.

Her deep humanism makes her register her revulsion through her superbly rendered, tragically resonant images. Arpita through her works reacts directly to the shattering reality of the world outside. She seems to indicate that beneath the surface beauty, there are roiling undercurrents and it is best to bring them out in the open. At first glance, Arpita Singh's world seems timeless, serene and unrushed. But there is trouble in paradise and the artist's unflinching eye refuses to ignore it. The tranquility created by earthy colours and balanced compositions is invaded by daggers, guns, cars, arrows, airplanes. They address a stoic acceptance of contemporary life's complexity and contradiction.

Alongside the simplifications of forms and figures that she has evolved, she has built a complex imagery and structure. She imbues the play-world that she creates on her canvas with an acute sense of vulnerability. The moment she portrays is fragile, tenuously poised between happiness and disaster. The exuberant colours counterbalance the melancholy thoughts and dark irony. It is easy to be beguiled by the glittering surface of her oil paintings but there is always the subtle hint, like the clues that she scatters on her canvas, to probe a little below the surface till the awareness of the dimensions of another reality grips the viewer. One of the foremost modernists, Arpita has absorbed the tenor of her times and reflects post-modernist aesthetics with ease. A formidable painter, Arpita Singh has left her indelible mark on modern and contemporary Indian art.