- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

An insight into the artistic journey of Gulam Mohammed Sheikh.

by Koeli Mukherjee Ghose

Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, born in 1937 in Surendranagar, Gujarat, studied in the Faculty of Fine Arts from the Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda and thereafter in the Royal College of Art, London. A founding member of group 1890, Gulam Sheikh's paintings evoke a reading of a narrative construction that also has an explicit physicality of space other than the sense of involved substances of description, an amalgamation of the apparent visual and an imagined verbal that Betty Seid appositely describes “as stories within stories.” In the beginning of his artistic journey he saw the crossroads of the international modernism and the path leading to the quest for an indigenous identity. For the artists in India then (1960 80) the intention could have been that of making a choice but what apparently seemed as distinct paths, merged and crystallized into a mass of data, this was and still is employed as language that characterizes modern art in India.

Gulam Sheikh's paintings signify a multipart scaffold, he acquaints this construction with tales that contain the strain from the past and erupt with the present. The structure and its melting into events are visible as a characteristic form since his exhibition of 1963.  In effect the paintings mention the mystic lore but they are iconic in terms of his concern for society.

In effect the paintings mention the mystic lore but they are iconic in terms of his concern for society.

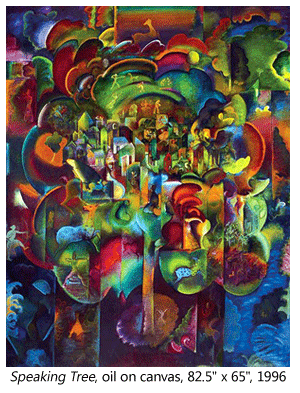

His works of the early 1960's featured the semi abstract in impasto but towards the end of the decade the turn of phrase was that of incandescent, warm and open landscapes. “The images of trees soaring high above the horizon and the roots”- bring in to discussion the notion of the spirit and the matter. This change came as a development due to his exposure to the Indian and Persian paintings that he studied in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London on a student fellowship in 1963 66.

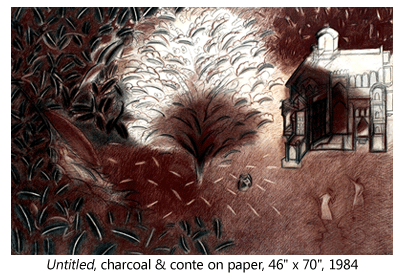

The studies stirred a re-examination of his training in art school, as well as the ideals that separated the traditional and modern styles of paintings. Neelima Sheikh in her essay, Thresholds and Courtyards, a Publication of Contemporary Art in Baroda, informs that “elements such as the lack of linear perspective in Mughal paintings or the brightness of the Rajput paintings which had made these paintings less realistic to an eye schooled in a western brand of realism turned out to be deeply related to the experience of the environment.” She describes his painting titled Wall of 1976, painted in oil that demarcates Gulam Sheikhs revisiting of Mughal perspective and a consequential soaking up of the experience of - “changing horizons which one comprehends in the courtyard secured on the near side of the canvas and a hilly terrain of dazzling intensity above and beyond. The wall separating the two areas is pierced by a half open door, where the rustle of pages from a half open book suggests interaction between the worlds meeting at the threshold.” She brings to notice the gradual evolution as Gulam Sheikh's walls attained a unique permeability in his paintings of the early 1980's, as the artist intended the threshold to situate, encounter and exchange. The place and its human measure developed into a combined motif of boundary, collapsing his own idea of the unified space “or even a dualistic one” that he communicated in his Wall Series. However as the allegorical homecoming he chose his own context with clarity - elements that signified his personal experiences and narratives that are disseminated as a part and parcel of genealogical inheritance, were placed as a thick layering of cultural matter as he lead the viewer in a visual perambulation into his own constructions of memory, of travel, of moving into and out of spaces.

His knowledge of history and an understanding of the traditional methods of painting and sculpting created characters in a play of - line and depth,  of reality and vision, weaving disparate contexts into a unified mass.

of reality and vision, weaving disparate contexts into a unified mass.

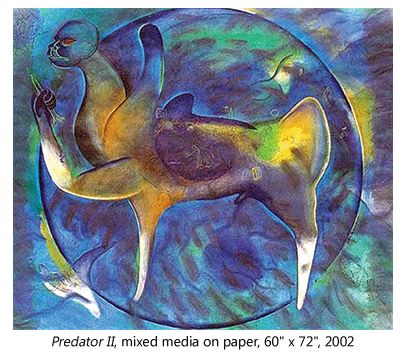

The artist's scheme of breaking the canvas into small fragmented planes creates a sense of the shattered picture plane that confine the substance of his narrative. This breaking up of space allows more view of the city. “The painter is a structuring principle in all Sheikhs' paintings” elucidates Nilima Sheikh in her essay. The motif for Sheikh's City is the crucial courtyard .The painting titled the City for Sale that he painted in the eighties erupts with the imagery of this noble courtyard and how it is stirred up with the subject of Baroda's communal riots. The artist also infused a sense of possibilities for the resurrection of hope by painting the allegoric rendering of the eye, suggesting a vision for the ethically blinded.

The artist's understanding of the element of space, the movement that could be created around it and its signification is articulated in his writing Ruminating on Life of the Medieval Saints by Benodebehari - “There is no doubt that Benodebehari developed an ingenious vision to suit his choice of painting scrolls and murals. It is tempting to see the beginnings of this mobile vision in his early attachment to books and the walks of his childhood; in the unfolding of sequence, the adjustment of eye and body to grasp the emergent, and, with his impaired vision, negotiating a realignment of the close with the distant. The elements of eye time involved in scanning pages and of body time in walking the mural space are central to these preferred formats. What might have been a natural preference was compounded by the desire to encompass a hitherto unexplored art historical range into his work, one feeding into the other.  He painted the Birbhum countryside: the ravines of the khoai (eroded barren land) with a not a soul in sight, as well as the village enveloped in lush foliage and with birds and animals astir with life. In constructing these he drew upon devices from diverse traditions and histories, mostly Asiatic involving a sequential opening of images. Far Eastern hand scrolls require a lateral extension of the optical vision, whereas in the mural and folio painting traditions of India, especially of late Mewar, terrains are mapped in emulation of a 'walking eye', round and about.” The piece reflects Gulam Sheikh's firm grasp in reading the image and reaping context in the image and the viewer notices a similar negotiation of realignment of the close with the distant, that of the eye time with the physical sense of the painting, the recalling of history and diversity in Gulam Mohammad's work. A strong adherence to the time perspective relationship becomes apparent too in the titles that set the clock to reverberate a range of time zones.

He painted the Birbhum countryside: the ravines of the khoai (eroded barren land) with a not a soul in sight, as well as the village enveloped in lush foliage and with birds and animals astir with life. In constructing these he drew upon devices from diverse traditions and histories, mostly Asiatic involving a sequential opening of images. Far Eastern hand scrolls require a lateral extension of the optical vision, whereas in the mural and folio painting traditions of India, especially of late Mewar, terrains are mapped in emulation of a 'walking eye', round and about.” The piece reflects Gulam Sheikh's firm grasp in reading the image and reaping context in the image and the viewer notices a similar negotiation of realignment of the close with the distant, that of the eye time with the physical sense of the painting, the recalling of history and diversity in Gulam Mohammad's work. A strong adherence to the time perspective relationship becomes apparent too in the titles that set the clock to reverberate a range of time zones.

Gulam Sheikh's pre concern is to purport a facsimile to express diagrams of interconnections between people, culture and events gets replicated in his image-chronicles of the - 'scroll book, shrine repository and map memoirs' that are deliberate multi cultural amalgamations. He appropriates a robust opulence of thought as an inherent discursive element. His paintings enact and inform in a scholastic capacity that the world is a tree, bearing the fruit of languages.

In his brief overview Dr. Shivaji K. Panikkar in the essay - Indigenism : An inquiry into the quest for Indianness in Contemporary Indian Art mentions “in the heart of the figurative narrative movement, Gulam Sheikh with his seminal narrative painting titled returning home after a long absence (1969-73) introduced the contrasting languages of western realism in the foreground figure of his mother's portrait ,with a background of an idealized medieval world, the language of which derives from various traditional miniature paintings styles. Through idiosyncratic stylizations and compositional devices, Sheikh narrativises cultures and people, much like an epic fabulist,  using traditional pictorial techniques.” While Dr. R. Sivakumar in his essay elucidates the same image as, “His first definitive contribution to this rediscovery of native identity came in the form of a painting meaningfully titled 'Returning Home after a Long Absence'. For him returning home meant connecting art back to a familiar world - to the environment and to the people he had left behind to pursue modernism to the myths and stories that sustained them, to the traces of places, lives and times transmitted through their memories and histories. Among other things this helped him to look beyond the confines of classical and courtly traditions which characterized Indian art to earlier identity seekers and to take notice of what lay outside the enclosure of high art.”

using traditional pictorial techniques.” While Dr. R. Sivakumar in his essay elucidates the same image as, “His first definitive contribution to this rediscovery of native identity came in the form of a painting meaningfully titled 'Returning Home after a Long Absence'. For him returning home meant connecting art back to a familiar world - to the environment and to the people he had left behind to pursue modernism to the myths and stories that sustained them, to the traces of places, lives and times transmitted through their memories and histories. Among other things this helped him to look beyond the confines of classical and courtly traditions which characterized Indian art to earlier identity seekers and to take notice of what lay outside the enclosure of high art.”

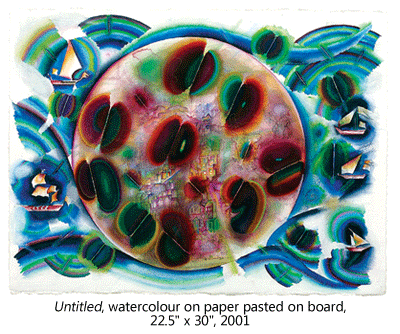

Geeta Kapur in elucidating the context of Gulam Sheikh's 'renegotiation' of the International modern and his traditional identity, refers to his notion of narrating with a surfeit of signs that recall a range of ethnicities and ways of life. This is vivid in his statement in 1981 “Living in India means living simultaneously in several times and cultures, one often walks into medieval situations and primitive people. The past exists as a living entity alongside the present, each illuminating and sustaining the other as times and cultures converge, the citadels of purism explodes. Traditional and modern, private and public, the inside and the outside are being continually splintered and reunited. The kaleidoscopic flux engages the eye and mobilizes the monad into action ….like the many eyed and armed archetype of an Indian child soiled with multiple visions; I draw my energy from the source.”

In his strong affirmation of a regional and an appropriately distinguished visual language Geeta Kapur finds him in the embrace of the post modern aesthetes, the images speak of many things at once. She explicates that the art historical references, the appropriation of the popular idiom sets free his expressions from its formal constraint revealing the inherent critical vision. In Gulam Sheikh's work images attend to intricate spatial and analytical contact, the contact between people; civilization, poetry and spirituality are essentials in the paradigm of his mark. This multitude of information breaking into a visual verbal play indicates an eclectic stimulus at work in the moment of telling.