- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

Profile

by Rita Datta

When it comes to Bikash Bhattacharjee, you must begin with ways of seeing. All art, to be sure, is about ways of seeing. Particularly, representational art. Artists see things differently from you and me. Where you'd see only a urinal, artistic vision discovers a fountain. Would any New Yorker recognize Broadway from Mondrian's Broadway Boogie Woogie? And though you are able to make out that somebody is screaming in fear or horror, have you ever actually seen any Norwegian look quite like the skeletal figure in Munch's iconic work?

have you ever actually seen any Norwegian look quite like the skeletal figure in Munch's iconic work?

Much of modern art, thus, keeps the viewer in a state of overawed mystification: and, of course, far away from the galleries. But with Bhattacharjee, you seem to immediately feel comfortable. He seemed to see what you see. So that you not only see but also recognize the images. Somebody's face, perhaps, or the just-so folds of a sari; an unkempt desk or a period terrace. If a caption says Kakima you linger over the portrait because you might think you know her or maybe somebody very much like her. A boy by a marshy pond may not have clear features but his distended tummy, lean limbs and, above all, the very way he stands declare both his village identity and a barely-veiled curiosity about someone or something outside the frame. When a sacrificial goat looks back at you in mute resignation you feel, yes, yes, you've seen it before, seen it many times in fact.

And yet, not quite. Because he saw what you saw, but not in the same way. Bhattarcharjee's lens would lend a startling twist to a known scene so that it became somehow different, unique. So that something you had seen so often and had grown stale and lost its particular visibility, was reborn. So that it became art, and not just faithful illustration.

Bhattacharjee's strategy, in other words, was one of subversion rather than revolution. He only rarely inflicted the big theme on you or the big style. Like the American artist Andrew Wyeth whose influence he repeatedly stressed it was usually the everyday, the known and the seen that he adopted as his subject, meticulously rendered, but skewed with disconcerting twists and smudges, highlights and shadows, into a beguiling image on the canvas.

If you look at his watercolours and oils what strikes you most is the flux implied beyond the frame. As though he had just intruded upon a narrative flow in which the bizarre seems to lurk just beyond the banal, and picked out a moment of critical disjunction or paused to freeze it. For, there's always a palpable refrain of the before and the after, in the now, of uneasy shades beyond the apparent.

And that's what makes you think of another important influence on the artist: Italian neo-realist cinema, which wove delicate tapestries of minutiae as the ambience into its humanist concerns. For Bhattacharjee, too, an inclusive humanism, the core allegiance of his generation of educated and mostly left-leaningBengalis, is the wellspring of his art. And, like the best of neo-realist films, it is the minutiae, the little physical details that help his art both transcend the immediate and mediate between different narrative layers, the socio-economic and the psychological.

Bhattacharjee, who was born in 1940, lost his father at the age of six and grew up in North Kolkata during a period of seminal socio-political churning famine, communal riots, the Partition and the Independence which also led to a massive displacement of people. But it wasn't so much the forces of History that he lived through in the mid-1940s the violence and deaths and avalanche of refugees that came to haunt his art as they did in the case of some his senior contemporaries, Somenath Hore, Zainal Abedin and Chittaprasad or those of his own generation like Ganesh Pyne and Jogen Chowdhury.

What proved to be more crucial to his creative inspiration in the initial years was his private lore. His relationships with people and things and the neighbourhood, observed, absorbed and recreated, with empathy but not without a lode of irony or even, at times, anger. For while he was a participant in this life he was also, simultaneously, an observer. He was, thus, both chronicler and critic in probing the milieu he had grown up in. It was a milieu that was very Bengali, very North Kolkata, a locale of strange juxtapositions: grand old mansions besieged by signs of imploding decay; dour middleclass respectability and low life festering in dark, cramped alleys. Its street urchins and widows, its marble statuary and tiled floors, its deities and pujas would come to inhabit his canvas. Indeed, he was as rooted to his locale and social milieu as Wyeth was to his.

The one period that did leave a permanent impact on his art was the early 1970s when, for a few years, the city came to be gripped by what today's Communist establishment would surely call an “infantile disorder”.  The frustration simmering among educated young people can't be explained merely in material terms: the lack of jobs and the Congress party's machinations to regain and retain power. Their despair over the Left's increasingly comfortable relation with parliamentary democracy, despite the Left's vocal opposition, would also have stoked rebellious ardour. With sneak strikes by the Naxalites leading to daily body counts and retaliatory searches, killings and torture by the police, a climate of fear and suspicion had enveloped the city. This was the time when the artist's Doll series was seen, making Bikash Bhattacharjee a well known name in the field of art.

The frustration simmering among educated young people can't be explained merely in material terms: the lack of jobs and the Congress party's machinations to regain and retain power. Their despair over the Left's increasingly comfortable relation with parliamentary democracy, despite the Left's vocal opposition, would also have stoked rebellious ardour. With sneak strikes by the Naxalites leading to daily body counts and retaliatory searches, killings and torture by the police, a climate of fear and suspicion had enveloped the city. This was the time when the artist's Doll series was seen, making Bikash Bhattacharjee a well known name in the field of art.

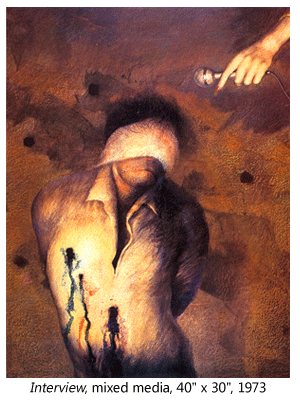

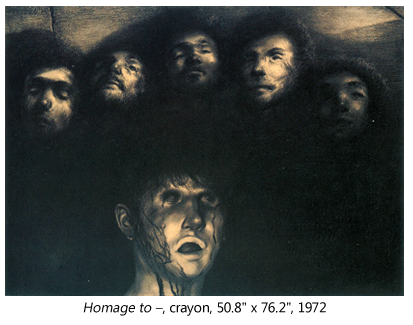

What was remarkable about these paintings was their insidious disquiet. There was no reference to violence. But to see a doll rummaging, frantic, in a chest of drawers, high above the ground, its chubby legs hanging dangerously; or to see it emerge, warily, from behind a blind, rundown wall, summons the kind of precarious dread and bewildered vulnerability people felt at the time. Other works where violence was shown are as powerful with their mix of emotion, acid and anger. The ethical humanist in Bhattacharjee spoke in a clearer voice in Homage to… Its bouquet of heads is curiously lambent in the dark. Five are dead but made to look innocuously asleep and one is dying. Evoked with a few deft touches of the crayon, it is an image that transcends the local narrative to turn into a universal image: of adolescent romanticism and protest quashed by brutal State power. Another well-known work, Interview-which has a lady's manicured hand hold a mike to a blindfolded and bleeding young detainee who could even be dead-isn't just sharp in its comment on the media but on the public itself which devours strident coverage.

Indeed, a few deft touches were all it took for the artist to infuse lines and shadings and strokes with atmosphere, with luminous life. He lent amazing yet elusive body to the limpid glow of watercolour, best seen in his Dekhi Nai Phirey series. Some of his conte/graphite/pastel works, on the other hand, were archly reticent, often playing up the texture of the medium and the surface on which they were executed. In fact, every medium, whether oil, gouache, watercolour, pencil, pastel, or conte, was slave to his will, as he disrupted photographic realism into the extra-real, the strange, the fantastic, and the sinister with surprise dislocations, insertions and smudges, slivers and pinheads of highlights and a web of shadows that, particularly, sculpted faces into probing portraits.

And indeed, his portraits especially of women are some of the finest examples of his artistry, whether of an anonymous Muslim woman, Laila, or the assassinated Indira Gandhi.  That he wasn't seduced from his kind of exacting verisimilitude into expressionist distortions or abstraction at a time when Clement Greenberg's damning of “illusionist methods” had come to be accepted as an axiom of modern art, speaks of his honesty to himself. He never hesitated to list the artists who inspired him: Rembrandt and Vermeer, among others, and even Sargent and Whistler, and, of course, Wyeth; Abanindranath, and particularly the Arabian Nights series, and the style of Hemendranath Majumdar.

That he wasn't seduced from his kind of exacting verisimilitude into expressionist distortions or abstraction at a time when Clement Greenberg's damning of “illusionist methods” had come to be accepted as an axiom of modern art, speaks of his honesty to himself. He never hesitated to list the artists who inspired him: Rembrandt and Vermeer, among others, and even Sargent and Whistler, and, of course, Wyeth; Abanindranath, and particularly the Arabian Nights series, and the style of Hemendranath Majumdar.

He thus declared quite openly that his style was not original. But in choosing trompe l'oeil as his métier, he bore the daunting heritage of the Renaissance and the masters of representational art. Few here had the technical felicity to dare in this direction. And yet, easy skill may not always stimulate creativity. If just a few strokes are all it takes to produce an eye-catching picture to be snapped up by the market, there's bound to be unevenness in standards.

Like most creative people, whether artists, film-makers, musicians or writers, Bikash Bhattacharjee didn't always produce great art, despite his unerring technique. But, interestingly, his last few exhibitions revealed a new direction in his work, a new timbre in his tone. He was moving away from the style he had been working on to a more turbulent, expressionist idiom. Could it be that he had reached the limits of his kind of realism and felt the need for a greater thrust to portray the 1990s and the early years of the new millennium? Religion was being crafted into a poisonous and violent weapon; the economic and social ideals of the 1960s were being casually upturned; a new kind of terrorism was taking shape; and the Left was increasingly seen to be without a conscience. Could it be that the nightmare images he had made in the late-1990s and the early 21st centurythe fierce beasts, ruthless police and grovelling sub-human beings under dark skies (Quest No 1 and Quest No 2) or a crass and hardened public figure in a welter of seething, surging paint (Inauguration of a Letter Box)-reflected a growing cynicism? Though it's pointless to speculate, the thought is inescapable. Was he, perhaps, on the verge of creating something completely different, something art-lovers were yet to see? There's no answer to that question because now we shall never know.