- Prelude

- Editorial

- A Conversation with Jagdish Swaminathan

- Seeing is Very Important………

- Tormented Delineations and Violent Deformations

- Bikash Bhattacharjee: Subverting the Seen

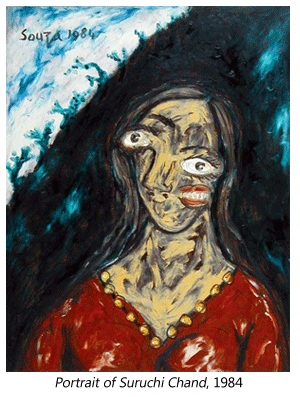

- Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

- Contesting National and the State: K K Hebbar's Modernist Project

- The Allegory of Return into the Crucial Courtyard

- Knowing Raza

- The Old Story Teller

- Beautiful and Bizarre: Art of Arpita Singh

- Feeling the Presence in Absence! Remembering Prabhakar Barwe

- Waterman's Ideal Fountain Pen

- Peepli Live: the Comic Satire Stripping off the Reality of Contemporary India

- Age of Aristocracy: Georgian Furniture

- Faking It - Our Own Fake Scams

- Scandalous Art and the “Global” Factor

- The Composed and Dignified Styles in Chinese Culture

- Visual Ventures into New Horizons: An Overview of Indian Modern Art Scenario

- The Top, Middle and Bottom Ends

- Top 5 Indian Artists by Sales Volume

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- The Month that was

- NESEA : A Colourful Mosaic

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Events Kolkata

- Musings from Chennai

- Art Bengaluru

- Khoj, Kolkata Boat Project

- What a Summit!

- Ganesh Haloi at Art Motif

- The Other Self by Anupam Sud at Art Heritage, New Delhi

- Baul Fakir Utsav at Jadavpur

- Printmaking Workshop

- World's Greatest Never Before Seen Toy and Train Collection

- Previews

- In the News

- Christies: Jewellery Auction at South Kesington, London

ART news & views

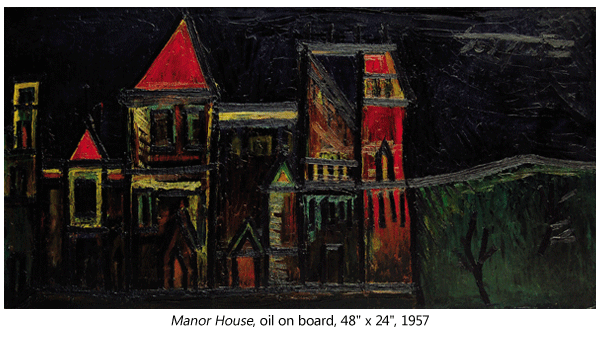

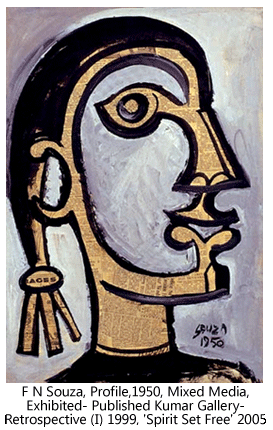

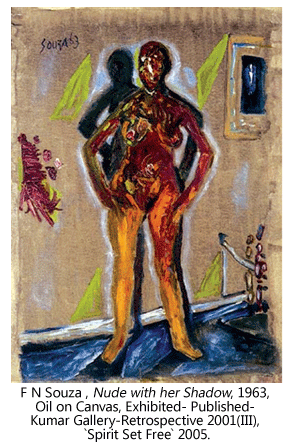

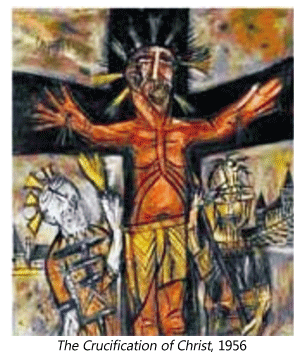

Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art: Francis Newton Souza

Volume: 3 Issue No: 13 Month: 2 Year: 2011

by Uma Nair

“Drawing is the school of hard knocks the artist has to go through before he or she can come into the bright sunlight of colour." (F. N. Souza, 1983, from Francis Newton Souza: Bridging Western and Indian Modern Art)

As an artist , both nurtured and tortured by his divided sensibility, his forked tongue, his inarticulate rage which found statement both in vibrant colour and in evocative prose: "I myself read, write and think in a language alien to me: English, a language not my mother tongue but spoken to me by my mother since my childhood. But the difficulty arose from the very start to express myself. For how can one articulate in Anglo-Saxon with a jewelled mandible that was fashioned by the ancient Konkan goldsmiths of Goa? It bewilders me to think that my inarticulation was due to England having possessed a lot of boats, which had netted India into its vast Empire."

No Indian contemporary artist was as raw, or magnetic as the maverick Francis Newton Souza. Among the many show held in India, it is the Kumar Gallery that had a series of shows which reflected the sweeping range of his subjects on paper as well as canvas.  Charting Souza's course from paper to canvas, reveals his incomparable talent as a draughtsman, which provided what he called “the structure of my iconography”a structure present in all his work, whatever the medium. Souza was someone who could paint as well as write.

Charting Souza's course from paper to canvas, reveals his incomparable talent as a draughtsman, which provided what he called “the structure of my iconography”a structure present in all his work, whatever the medium. Souza was someone who could paint as well as write.

“I disembarked at Tillbury on a hot August day in 1949 with 15 pounds in the pocket of my only suit. In London I took up Lodgings on my own. I bought paint and brushes with 10 pounds and spent the rest on food and a week's rent [...]. I felt awfully alone in the largest populated city in the world.” (F. N. Souza quoted in Francis Newton Souza: New York and London 2005, exhibition catalogue, Grosvenor Gallery, 2005, p. 97)

The London in which Souza arrived was gripped by the gloom of post-war austerity and continued rationing, still smarting from the scars of its immediate past. Championing a post-colonial zeal following India's Independence,  the artist set out to take London by storm and this painting is a fundamental early work demonstrating his desire to innovate. Evidently he developed a fascination with collage and juxtaposition, and significantly this work numbers amongst the earliest compositions using printed media as a 'canvas' – quite literally, as a picture within a picture. This female figure similarly reinterprets Byzantine portraiture in the foreground, against two architectural structures in the background, creating a compositional balance that utilizes Souza's characteristic thick, black lines.

the artist set out to take London by storm and this painting is a fundamental early work demonstrating his desire to innovate. Evidently he developed a fascination with collage and juxtaposition, and significantly this work numbers amongst the earliest compositions using printed media as a 'canvas' – quite literally, as a picture within a picture. This female figure similarly reinterprets Byzantine portraiture in the foreground, against two architectural structures in the background, creating a compositional balance that utilizes Souza's characteristic thick, black lines.

Insatiable intellectual curiosity and patriotic fervor propelled an artistic revolution beginning in 1947, with Souza at the helm – referring to the first Progressive Artist's Group exhibition, he declared: “Today we paint with absolute freedom for content and techniques. We have no pretensions of making vapid revivals of any movement in art. We have studied the various schools of painting and sculpture to arrive at a vigorous synthesis.” (F. N. Souza, quoted in the first Progressive Artist's Group exhibition catalogue, in Y. Dalmia, The Making of Modern Indian Art)

Whether he created disintegrated heads, or landscapes in New York's mood, or Europe's skyline with the church, or just his Eucharistic still lifes-each subject grew in passionate intensity and the hallmark of balance and the physicality of a dominance of the potency of knowing that the contour was what characterized the still life.  Souza's still-life paintings were often vested with an element of the sacred. In these works, the reference to the Catholic Church and it's rituals is exemplified through the inclusion of a prominent crucifix, a golden chalice, and an open book suggesting the Holy Bible. The careful selection and placement of objects simulates the appearance of an altar set for mass.

Souza's still-life paintings were often vested with an element of the sacred. In these works, the reference to the Catholic Church and it's rituals is exemplified through the inclusion of a prominent crucifix, a golden chalice, and an open book suggesting the Holy Bible. The careful selection and placement of objects simulates the appearance of an altar set for mass.

Rooted in religion, the rural setting and the resonance of an emotive and evocative residue, each work by him is a beauty to behold. The bold outlines and cross-hatched depth of his drawings translate beautifully to the canvas with Souza's towering masterpieces. Souza perfectly captures the resignation in the eyes of the wildebeest being attacked by a tiger and a lioness, while also touching on the broader concept of the natural circle of life. The pared-down background, distinguished by its earth tones and a few scattered clouds hovering overhead, balances out the aggression of the beasts that occupy the center of the canvas. Harmonizing the compositional tension between force and restraint was one of Souza's many artistic attributes.

Souza was known for his blatant honesty-and left us awe-struck and forewarned, “Why should art be pretty pictures? Art isn't derivative. It's what lies deep within. I often try to paint a hideous picture, and I bloody well succeed." He said, "You call my Heads a distortion, I call it reality.  I started using more than two eyes, numerous eyes and fingers on my paintings and drawings of human figure when I realized what it meant to have the superfluous and so not need the necessary. Why should a face be beautiful? Why should I be sparse and parsimonious when not only this world, but worlds in space are there for me to explore? Art is using everything at our disposal."

I started using more than two eyes, numerous eyes and fingers on my paintings and drawings of human figure when I realized what it meant to have the superfluous and so not need the necessary. Why should a face be beautiful? Why should I be sparse and parsimonious when not only this world, but worlds in space are there for me to explore? Art is using everything at our disposal."

Souza's treatment of the human figure was richly varied. There is a razor edged rawness that stirs you-it is the split-open zeal of a prophet who walked the road of distortion. Besides the violence, the eroticism and the satire, there is a religious quality about his work, which is medieval in its simplicity and its unsophisticated sense of wonder. Some of the most moving pictures convey a spirit of awe in the presence of a divine power – a God, but this is not a God of gentleness and love, but rather of suffering, vengeance and grotesque grandeur.

“Evil is greater than good,” wrote he, “greater than God, positive, devastating, intolerant. And when you choose evil you can't throw bones of contention away. You will have to chew them yourself and like them.”