- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Feature

by Snehal Tambulwadikar

The notion that all great styles are the expression of different and incompatible ways of viewing the world- that, for instance, a Chinese sees ‘through the Chinese eyes’- has become singularly unconvincing now. This mistaken idea that man’s visual habits are determined by geography has been carried a stage farther, and extended to include history too.1 In the contemporary methodology, one can say that that the place of geography has been taken by sociology, where artists of one era and area are taken to be inspired by singular notion of art and their art is seen through particular notion. K.H. Ara, from the Progressive artists’ group has been overshadowed with similar methodologies. The Progressives, Souza, Raza, Ara, Gade, Bakhre and Husain, who rebelled the academics and the Bengal nationalists for their individual autonomy, dispersed in a short time, with the likes of Souza, Raza and especially Husain rising to fame. Ara, though successful, never seemed to have enjoyed the glamour.

Krishnaji Hawlaji Ara was born in Bolaram near Hyderabad in April 1913/14. He lost his parents at a very early age, mother at 3 and father at 10, between these 7 years he went through troubles under his step-mother. These are the few facts known about his family which ceased with his ‘unmarried’ life. Coming to then ‘Bombay’ at the age of 7, Ara got the first patron, a European woman for whom he worked as domestic help. In 1930s, he continued to work for Englishman C.C.Gullielan, who encouraged his interests. Meanwhile, he got involved in the Salt Satyagraha and got arrested and then released but he was jobless. Getting a job for car cleaning in a Japanese firm, he also secured a place for himself in Walkeshwar, a small room of 10x10ft, which continued as his studio for the rest of his life. He, along with Husain had no orthodox art education (these were the only amongst Progressives without formal education), Ara was rather devoid of any kind of education. With this and only this information about his early life and a gamut of mostly undated works, one begins studying Ara.

Krishnaji Hawlaji Ara was born in Bolaram near Hyderabad in April 1913/14. He lost his parents at a very early age, mother at 3 and father at 10, between these 7 years he went through troubles under his step-mother. These are the few facts known about his family which ceased with his ‘unmarried’ life. Coming to then ‘Bombay’ at the age of 7, Ara got the first patron, a European woman for whom he worked as domestic help. In 1930s, he continued to work for Englishman C.C.Gullielan, who encouraged his interests. Meanwhile, he got involved in the Salt Satyagraha and got arrested and then released but he was jobless. Getting a job for car cleaning in a Japanese firm, he also secured a place for himself in Walkeshwar, a small room of 10x10ft, which continued as his studio for the rest of his life. He, along with Husain had no orthodox art education (these were the only amongst Progressives without formal education), Ara was rather devoid of any kind of education. With this and only this information about his early life and a gamut of mostly undated works, one begins studying Ara.

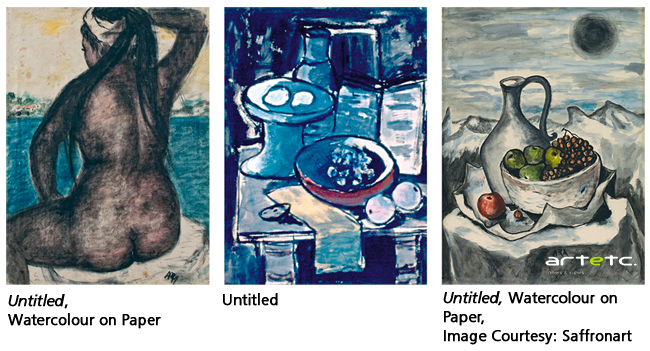

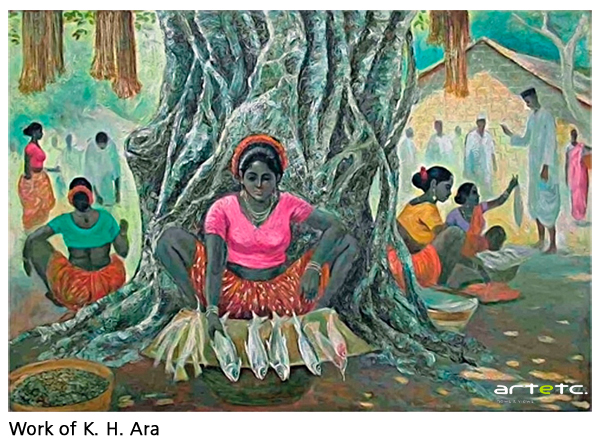

The early works of Ara were versatile, the easy depictions of life, like Dance, oil, 1941(Mr. R.V. Leydon collection) or Bazaar, ink, 1944 (Private collection). In 1939, he won the Times of India prize no.2, when he must have been acquainted with the art critic Rudy Von Leydon and Walter Langhamer the then director of art, who encouraged him throughout his life. With his painting Flora Fountain getting good appreciation, Leydon saw the genius, and helped him for a solo exhibition in the hall of Bombay Art Society, Rampart Road (today’s Artist Centre) in 1942, which had water colours and oils both.2 Ara received the Governor’s prize in the Bombay Art Society (Maratha Battle, water colour) in 1944. With these achievements and through Leydon, Ara came into contact with his young contemporaries, and must have been highly influenced by the strong headed Souza, himself been a rebel all the way. With the fervour of independence, he painted a spontaneous work of monumental size (240x36 in), Independence Day Parade, in oil, currently in Vidhanbhavan Mumbai. This work was rejected by the Bombay Art Society’s Annual exhibition, and was one of the significant points of discussion in the meeting of Progressives held in 1947.3 During this period Ara, different to his style painted subjects like beggars, prostitutes, gamblers and lunatics, projecting social consciousness. In the exhibition of Progressives, Bombay Art Society Salon, Rampart Row, 1949, which achieved great success, a critic wrote about Ara, ‘his aesthetics are intuitive and spontaneous, untrammelled by excess of thought and theory. In that lie his weakness and his appeal. His large cartoons of card players and beggars remind you of Peter Breughel in their human realism.’4

He seems to be freely working with all that came to him, the Bombay School style combined with the water colour wash of Bengal in some works. In 1952, the inaugural exhibition of Jehangir Art Gallery, Ara’s Two Jugs received the gold medal. In 1952, 54 and 60 he had his solos, while around 1955 he exhibited in places like Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, as also in East Germany, Russia and Japan galleries. In 1963, his series Black Nudes was exhibited. These visits made him acquainted with the masters of Europe, which brought about a change in his visual language.

Somehow after confluence with progressive/modern art, Ara reduced his art to still life, which after 1960 he coupled with his earthy, heretical nudes. Every art purporting to represent involves a process of reduction.5 In Ara’s case it might have reduced to visual subjectivity, the content have to be seen in better light. For a child, his gifts control him; he does not control his gifts and equally, while making his picture, Ara, gives the least possible attention to the spectators; painting, above all for himself. This charm comes to an end once his will intervenes. Even artist wants to depict what he sees, but a fact that being human means possessing, and man is possessed by himself with his knowledge. With the advent of the novel techniques adapted by progressives, Ara seems to have possessed his visuals devoid of earlier spontaneity. Is the artist’s life and his work deliberately separated here, or do they seem separate, the still lives opening to wide plains and nudes hiding the facets of Ara’s personality which seem simple but open and close to voids. Prof. P.A. Dhond when writing on then contemporary Bombay group, says,

Somehow after confluence with progressive/modern art, Ara reduced his art to still life, which after 1960 he coupled with his earthy, heretical nudes. Every art purporting to represent involves a process of reduction.5 In Ara’s case it might have reduced to visual subjectivity, the content have to be seen in better light. For a child, his gifts control him; he does not control his gifts and equally, while making his picture, Ara, gives the least possible attention to the spectators; painting, above all for himself. This charm comes to an end once his will intervenes. Even artist wants to depict what he sees, but a fact that being human means possessing, and man is possessed by himself with his knowledge. With the advent of the novel techniques adapted by progressives, Ara seems to have possessed his visuals devoid of earlier spontaneity. Is the artist’s life and his work deliberately separated here, or do they seem separate, the still lives opening to wide plains and nudes hiding the facets of Ara’s personality which seem simple but open and close to voids. Prof. P.A. Dhond when writing on then contemporary Bombay group, says,

‘Ara amongst them was a completely different artist. With his hair outgrown and tied in a bun on his neck and unruly strands over years, he still resembled his car cleaning days. Somehow his troubled life when young left permanent marks over his personality........even today if you meet Ara, you’ll find him carrying someone’s kids over his shoulder, if you ask, he would reply that they are his.’

Very interesting and rare piece about Ara; speaks of his personality of own and wanting to adapt the new of the others. In the case of Ara, the facts are so meagre that the methodology takes an about turn, where rather than studying the works through persona, one has to study the personality through works. On one hand making the still life lively, Ara freezes the nude studies to stills, he quotes, artists take out a piece of time from their or others lives and freeze the moments in their paintings. If at that time the artist has put a part of his life in the work, the work stays on for ten, twenty, fifty years, or else its dead then and there.’6 Is his work the broken fragments of his life, which are yet to be deciphered?

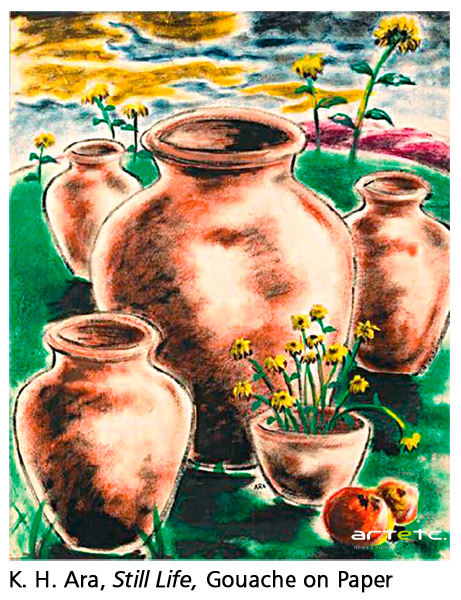

Ara’s body of work can be divided into three main categories, the still life, the nudes and the other depictions, which are few but significant. The still life is a combination of landscape and objects, a vase in the window opens up to the mountains behind, many times with flowers. The colours are extremely vibrant, flowers in full bloom. The vases seem to be standing in the space alone, in full spring, shining away to doom. In a spectacular work with yellow flowers where the background is a landscape with clouds of a good sunny day; the main vase is such that the skies seem naturally around them, and seldom does one wonder about the abstract conception. The semblance of subject of stills with Matisse do not necessarily show the influence of Matisse, rather is seems like a rebel vision of a common, present in every movement, like looking at the skies, with very mundane regular objects in focus. The use of light and white is specific to his style, along with the impasto effect, with the stills like visions from gaps in walls or holes in door. The work is not a landscape, neither is it the vase and the flowers, its Ara’s perception of self, done using the concept/percept at hand.

Ara’s body of work can be divided into three main categories, the still life, the nudes and the other depictions, which are few but significant. The still life is a combination of landscape and objects, a vase in the window opens up to the mountains behind, many times with flowers. The colours are extremely vibrant, flowers in full bloom. The vases seem to be standing in the space alone, in full spring, shining away to doom. In a spectacular work with yellow flowers where the background is a landscape with clouds of a good sunny day; the main vase is such that the skies seem naturally around them, and seldom does one wonder about the abstract conception. The semblance of subject of stills with Matisse do not necessarily show the influence of Matisse, rather is seems like a rebel vision of a common, present in every movement, like looking at the skies, with very mundane regular objects in focus. The use of light and white is specific to his style, along with the impasto effect, with the stills like visions from gaps in walls or holes in door. The work is not a landscape, neither is it the vase and the flowers, its Ara’s perception of self, done using the concept/percept at hand.

The nudes whom Dnyaneshwar Nadkarni calls sensuous and simple, are much intriguing, for their austere and earthy selves. No one knows of Ara’s model or muse for these, he never told anyone, even the closest of his friends, which made a few think he referred to porn magazines for the same. But Ara’s nudes are far from vulgar; rather some are shockingly comfortable with their nudity. They do not face the spectator, absorbed in their own world they are engrossed in various activities, plucking flowers, brooding, lying down comfortably, dark skinned and never posed. It seems incredible how Ara could draw nudes devoid of the gaze, almost as if they come out of his mind, the stills, frozen moments from negatives. In some pictures the nudes are coupled with still life, somehow one is confused whether the vase is in background or the nude. It’s not easy to be simple, the simplicity complicates the reasons behind the works.

The works of Ara where he painted other styles are few, in his early works, and Lest We Forget His Sacrifice in mid 1960s, for exhibition New Man held by Catholic Church for the 38th International Eucharist Congress.7 The work has Christ with nuclear bombs and mass destruction below, highly expressive work, and makes one think of possibilities Ara could have had, had he not restricted his styles. Ara at a singular time could have had impressionist and expressionist tendencies. An ‘impressionist’ eye, which depicted the captured visions and perceptions of heart for the visuals; like Jehangir Sabavala said, ‘Ara painted with this heart, not with his mind.’8 His works start with realistic probing, then into impressionist visions, and later going towards expressionist, some of his nudes remind Gauguin’s earthy figures. Though a member of PAG, Ara was much more than that, like most of our artists, he has been studied more through the period than as an individual; highly taken by the wave of his contemporary, Ara seems to have never ceased being his self, and his works show the same, his influences from various sources, yet effortless.

In the later years, after disperse of Progressives, Ara devoted himself to his work, and Artists’ Centre, which became his work space. For many years he was the secretary of the same. He would paint for days together, continuously, which make many of his works repetitive in later years. He could never enjoy economic prosperity, though sale of paintings was good. In 1965, the golden jubilee year of Ara, a show of all his paintings was held and price of each painting was Rs.100, he knew that his work had the essence of mass. Leading a lone life, he got solace in the family of his friend Hyder Pathan, and adored his daughter Rukshana like his own. He took workshops, helped young students, and guided them. Leydon finds his works poetic; Ara himself recited verses in urdu, shayari, with easy rhythm and simple truths of life. Like his still lives, he had a habit of collecting stills, photographs, newspaper-magazine cuttings, invites catalogues et al in Artists’ Centre. Unfortunately he did not welcome interference with his books and collections; and after his death, the room was cleaned of all the material without heed, which could have had much of the lost links of his life and that of the progressives.9 With the death of Ara in 1985 at Pathans residence, who was his only associate, an era came to an end.

Ara was not a spellbound personality, nor a path breaker, like Souza or Husain, his contemporaries. He came to forth with his retrospective in 199110 having numerous forgeries of his works, one would like to question why Ara. What was in his art that appealed, was it the raw untrained mind of his, or his very easy content of the still lives, the major body of his work. Ara is the complexity in every simple man. His art depicts the pleasure of ability of expression, thus his art is intriguing with its raw quality and yet cannot be subsumed from the main course of art history. History is not only of the Masters, it’s the making of masters and their contemporaries.

Reference

1. Pg 274, The Voices of Silence, Andre Malraux, translated by Stuart Gilbert.

2. In this exhibition Ara made a profit of Rs.2000, having success on both financial and artistic fronts. Ref. Sharmila Phadke and Nalini Bhagwat.

3. Ref. Nalini Bhagwat, Thesis is Development of Contemporary Art in Western India, 1983 (Ph.D. Thesis), Chap VI, The Progressive Artists’ Group (1947-53), the detail of meeting of the PAG, 5 Dec 1947, called for discussion of the current Bombay Art Society Exhibition, where Souza, Raza, Ara, Bakhre, Bharatan and critic Rashid Hussain spoke, and the rejection of Ara’s work was on e of the main points, as Ara spoke about the freedom of artist.

4. Review in the Times of India, dated 9 July 1949, ref. Nalini Bhagwat.

5. Pg 275, The Voices of Silence, Andre Malraux, translated by Stuart Gilbert.

6. Reference, Sharmila Phadke, Krishnaji Hawlaji Ara: Ayushyache Sthir Chitran.

7. Yashodhara Dalmia, the Making of a Modern Indian Art, Oxford Publication.

8. Reference, Sharmila Phadke, Krishnaji Hawlaji Ara: Ayushyache Sthir Chitran.

9. Ref. through an informal chat with Satish Naik, Artist, Editor, Chinha, Mumbai.

10.Ref, Sharmila Phadke, a retrospective of his works was held by Ashish Balram Nagpal in 1991, which had many Ara forgeries.