- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Feature

by Haimanti Dutta Ray

Artists have and tend to lead a very chequered life. It is far from easy to establish oneself in the field of visual arts. Success comes very late in life, if at all. Artists experiment in a variety of art forms because of this urge to express his/her creative self. This creative side of an artistic consciousness finds an expression and an outlet in paintings, sculpture, graphics and photography. Every artist known to mankind has had a very humble beginning. The artist is bound to face rejection at first amidst adverse or constructive criticism. This rejection, I feel, is very necessary and is the first building block in the ultimate process of the creative spirit.

.jpg)

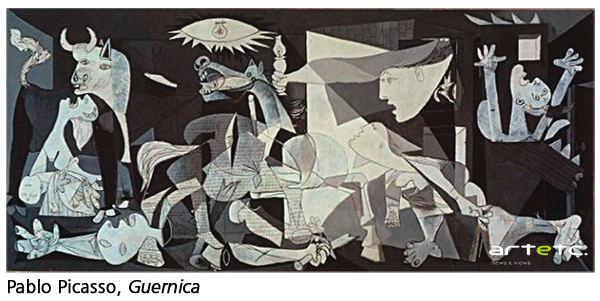

The human form and the human predicament in the context of the existing social scenario is the preoccupation of every visual artist. Through years of toil perfecting this human form, the artist expresses modern man’s angst. Pablo Picasso had said, “What interests me… is the drama of the human being, so to speak. The rest is not true to life.” Picasso had tried to explore the inner conflicts that reside and rule our soul. Anything external to the human psyche, he had found puerile. A propounder of Cubism, Picasso’s paintings possesses a predominantly graphic quality. His seminal work, Guernica (1937) is a painting without colour (a combination of grey, black and white) featuring instead powerful graphic elements. Living in abject poverty in the early stages of his career, Picasso painted the seamy side of Parisian urban lifestyle. Achromatism, monochromatism and the predominance of the blue-green harmonies are signally characteristic of Picasso’s work from 1901. He was to impart a still more radical edge to what he had achieved previously in his graphic work by favouring “drawing by shadows”. As a whole Picasso’s oeuvre adheres mostly to the Western tradition. He was much inspired, for example, by Durer, Cranach, Michelangelo, Titian, El Greco, Velasquez, Goya, Delacroix, Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, and , of course, Cezanne.

The human form and the human predicament in the context of the existing social scenario is the preoccupation of every visual artist. Through years of toil perfecting this human form, the artist expresses modern man’s angst. Pablo Picasso had said, “What interests me… is the drama of the human being, so to speak. The rest is not true to life.” Picasso had tried to explore the inner conflicts that reside and rule our soul. Anything external to the human psyche, he had found puerile. A propounder of Cubism, Picasso’s paintings possesses a predominantly graphic quality. His seminal work, Guernica (1937) is a painting without colour (a combination of grey, black and white) featuring instead powerful graphic elements. Living in abject poverty in the early stages of his career, Picasso painted the seamy side of Parisian urban lifestyle. Achromatism, monochromatism and the predominance of the blue-green harmonies are signally characteristic of Picasso’s work from 1901. He was to impart a still more radical edge to what he had achieved previously in his graphic work by favouring “drawing by shadows”. As a whole Picasso’s oeuvre adheres mostly to the Western tradition. He was much inspired, for example, by Durer, Cranach, Michelangelo, Titian, El Greco, Velasquez, Goya, Delacroix, Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, and , of course, Cezanne.

According to Jean Bazaine, “Nobody paints as he likes. All a painter can do is to will with all his might the painting his age is capable of”. And according to Picasso, “In the last analysis there is nothing but love, whatever form it takes. They really should put out the eyes of the painters, just as they do to goldfinches, to make them sing more sweetly.”

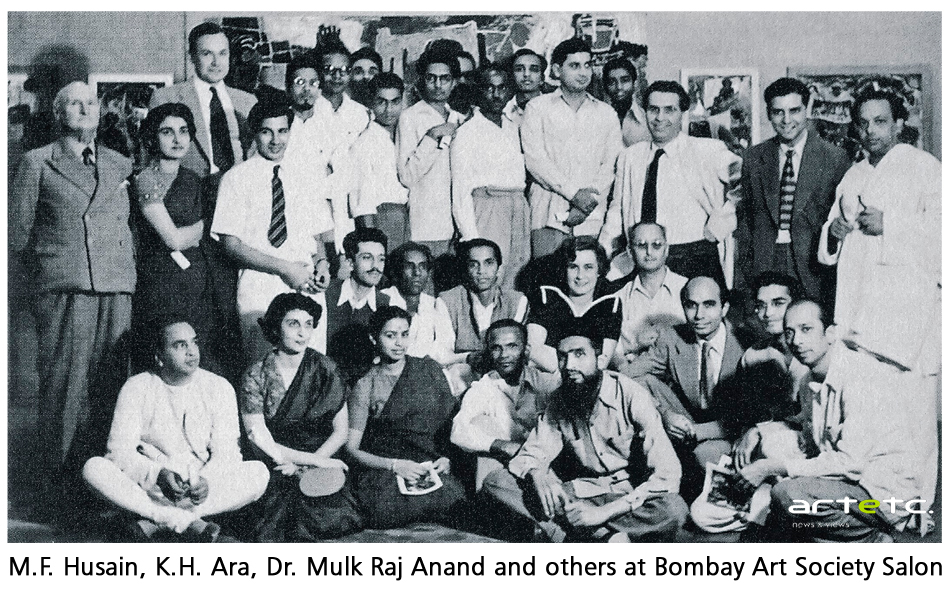

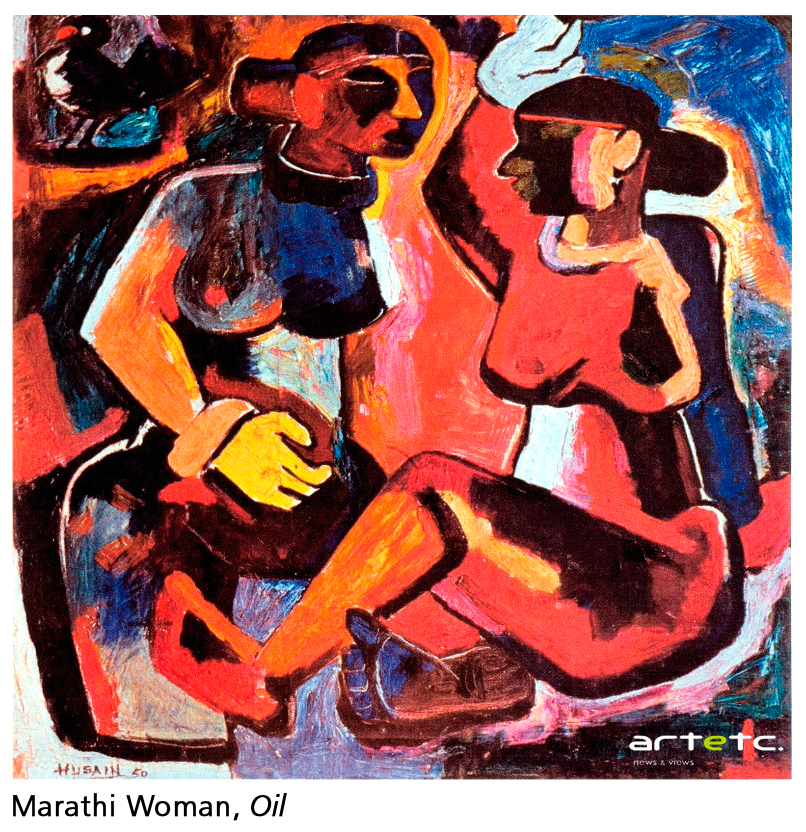

Maqbool Fida Husain has been called the Picasso of modern Indian art (17 September 1915 – 9 June 2011). He was primarily a self-taught artist. (Theories differ regarding Husain’s formal training. He has had no formal education in his student years. But today, scholars say that he had been to the J.J. School of Art, Mumbai). As we all know by now, Husain had made ends meet in his initial days by painting cinema hoardings in Mumbai, which paid him barely four-six annas per square feet. Husain had his early training in representational art. He became a legend in his lifetime, a man who delivers the common man from the ordinariness of his existence to the international arena. He was, at the same time, involved with language, with the formulation of modernity and with its rootedness in India. Husain’s early works - paintings like Marathi Women, Balaram Street, Mother and Child and Women at Work show strong, sturdy peasant figures, involved in their work with a certain air of grave dignity. They are located within the urban environment in a way that the village is ineffably placed in the city, yet retaining its peasant ambience. Husain was closely associated with Indian modernism in the 1940’s. In 1947, Husain took part in his first group exhibition held at the Bombay Art Society, and won an award for his work, The Potters. The work attracted the attention of Souza, who became a close friend of Husain and who invited him to join the Progressives. So as soon as our country gained independence, in Bombay the Progressive Artists’ Group was formed which became one of the most influential group of modern artists in India right from its inception. The group was formed by Francis Newton Souza and S.H. Raza. The group had combined Indian subject matter with post-Impressionist colours, Cubist forms and brusque Expressionist styles. M.F.Husain and Manishi Dey were early members, others included S.K.Bakre, Akbar Padamsee and Tyeb Mehta. The group wished to break with the revivalist nationalism established by the Bengal School of Art and to encourage an Indian avant-garde, engaged at an international level. In 1950, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, Krishen Khanna and Mohan Samant joined the group, following the departure from India of the two main founders Souza and Raza. Bakre also left the group. The group disbanded in 1956.

Maqbool Fida Husain has been called the Picasso of modern Indian art (17 September 1915 – 9 June 2011). He was primarily a self-taught artist. (Theories differ regarding Husain’s formal training. He has had no formal education in his student years. But today, scholars say that he had been to the J.J. School of Art, Mumbai). As we all know by now, Husain had made ends meet in his initial days by painting cinema hoardings in Mumbai, which paid him barely four-six annas per square feet. Husain had his early training in representational art. He became a legend in his lifetime, a man who delivers the common man from the ordinariness of his existence to the international arena. He was, at the same time, involved with language, with the formulation of modernity and with its rootedness in India. Husain’s early works - paintings like Marathi Women, Balaram Street, Mother and Child and Women at Work show strong, sturdy peasant figures, involved in their work with a certain air of grave dignity. They are located within the urban environment in a way that the village is ineffably placed in the city, yet retaining its peasant ambience. Husain was closely associated with Indian modernism in the 1940’s. In 1947, Husain took part in his first group exhibition held at the Bombay Art Society, and won an award for his work, The Potters. The work attracted the attention of Souza, who became a close friend of Husain and who invited him to join the Progressives. So as soon as our country gained independence, in Bombay the Progressive Artists’ Group was formed which became one of the most influential group of modern artists in India right from its inception. The group was formed by Francis Newton Souza and S.H. Raza. The group had combined Indian subject matter with post-Impressionist colours, Cubist forms and brusque Expressionist styles. M.F.Husain and Manishi Dey were early members, others included S.K.Bakre, Akbar Padamsee and Tyeb Mehta. The group wished to break with the revivalist nationalism established by the Bengal School of Art and to encourage an Indian avant-garde, engaged at an international level. In 1950, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, Krishen Khanna and Mohan Samant joined the group, following the departure from India of the two main founders Souza and Raza. Bakre also left the group. The group disbanded in 1956.

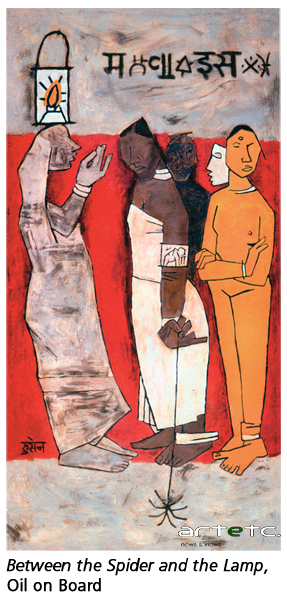

Husain, who had been a bohemian most his life, joined the Progressive Artists’ Group in 1947. As he had once said, “India was never a nation… This is the first time it is struggling to become a nation. It might collapse … the very fact that it is struggling is dangerous and exciting … This is perhaps the most exciting period in history… for me India’s humanity is what is important, not its borders.” Husain reached his apogee with the masterly work Between the Spider and the Lamp (1956). Three women stand against a swathe of passionate red bringing to mind the many ‘Indias’ that exist together. The alternative persona of the dark woman in spotless white suggests a complex duality between the repose of the archival mother earth and the anxious stances of the harried city dweller. Shown in profile is a village woman, without any assemblage of faces, heavy yet mobile, her portrait reminiscent of Indian miniatures. Unlike his contemporaries Souza, Ram Kumar, and Satish Gujral, who focused on the urban situation, Husain had looked towards the village, but only in a specific sense, where it formed part of the great gush of change that was sweeping across the country.

Husain, who had been a bohemian most his life, joined the Progressive Artists’ Group in 1947. As he had once said, “India was never a nation… This is the first time it is struggling to become a nation. It might collapse … the very fact that it is struggling is dangerous and exciting … This is perhaps the most exciting period in history… for me India’s humanity is what is important, not its borders.” Husain reached his apogee with the masterly work Between the Spider and the Lamp (1956). Three women stand against a swathe of passionate red bringing to mind the many ‘Indias’ that exist together. The alternative persona of the dark woman in spotless white suggests a complex duality between the repose of the archival mother earth and the anxious stances of the harried city dweller. Shown in profile is a village woman, without any assemblage of faces, heavy yet mobile, her portrait reminiscent of Indian miniatures. Unlike his contemporaries Souza, Ram Kumar, and Satish Gujral, who focused on the urban situation, Husain had looked towards the village, but only in a specific sense, where it formed part of the great gush of change that was sweeping across the country.

His preoccupation with horses is of world renown. According to an ancient Indian custom, a horse, ‘Ashwamedha’, was sent in all four directions to conquer territories. Likewise, Husain’s horse swept across continents, amalgamating various influences into a composite form. The Duldul horse, which he had seen from his childhood on ‘tazias’ in Muharram processions, had been modified, first by the Chinese rendering of the horse, and then by the plasticity of form in Franz Marc and Mario Marini’s balance between horizontal and vertical lines. Husain’s horses, however, are singularly his own. As a critic once wrote, “Husain’s horses are subterranean creatures. Their nature is not intellectualized: it is rendered as sensation or as abstract movement, with a capacity to stir up vague premonitions and passions, in a mixture of ritualistic fear and exultant anguish.” When Husain was compared to be on par with Pablo Picasso, he said about the latter, “Picasso created the language of modern art.” It was in the late 1960’s that Husain painted the Ramayana, which was followed by the Mahabharata Series. He was motivated by a desire to purge himself of an increasing distance from his roots. In negotiating the iconic, Husain had re-invested it with a mythic aura, restoring its original function. Half a century earlier, Ravi Verma had delved into Puranic and mythological texts and had introduced the gods as real men and women into his tableaux –like canvases. Husain, under modernism, empowered them with a symbolic presence while contextualizing them in the contemporary, thereby layering their form with multiple meanings. The artist himself became a phenomenon in his lifetime , something of a cult figure. With his flowing beard and barefoot appearance, he became both a Messiah and the itinerant wanderer, an image that is further heightened by his unconventional behaviour. Husain’s quicksilver personality found a resonance in everyone.

A dashing, eccentric figure, he always went barefoot which had become his trademark style and which had famously barred him from entering reputed clubs in the city Kolkata. He used to brandish an extra-long paintbrush as a slim cane. Enormously prolific by any standards, Husain is claimed to have produced over 60,000 works and had created four museums spread across the country to showcase his paintings. There is Husain’s Gumpha and Husain ki Sarai to name a few. He also had a classic collection of sports cars. He had applied the formal lessons of European Modernists like Cezanne and Matisse to scenes from national epics like The Ramayana and The Mahabharata as well as the Hindu pantheon. A Bohra Muslim, he had been a rebel both in his life as well as in his craft. He made Through The Eyes of A Painter in 1967 which had won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. In 1971, Husain was a special invitee along with Pablo Picasso at the Sao Paolo Biennale.

A dashing, eccentric figure, he always went barefoot which had become his trademark style and which had famously barred him from entering reputed clubs in the city Kolkata. He used to brandish an extra-long paintbrush as a slim cane. Enormously prolific by any standards, Husain is claimed to have produced over 60,000 works and had created four museums spread across the country to showcase his paintings. There is Husain’s Gumpha and Husain ki Sarai to name a few. He also had a classic collection of sports cars. He had applied the formal lessons of European Modernists like Cezanne and Matisse to scenes from national epics like The Ramayana and The Mahabharata as well as the Hindu pantheon. A Bohra Muslim, he had been a rebel both in his life as well as in his craft. He made Through The Eyes of A Painter in 1967 which had won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. In 1971, Husain was a special invitee along with Pablo Picasso at the Sao Paolo Biennale.

In a typical Husainesque fashion, his preoccupation with cinema seemed to be both the completion of a full circle and in stating that cinematic reality is the only true one a prophetic statement. He had scripted and directed the film Gaja Gamini which was in many ways an extension of his painted canvas. The script itself, with hieroglyphic marks, images and words written in Husain’s own slanting hand, is now available in a limited edition as a collector’s item.

Husain made Gaja Gamini dedicated to his muse, Madhuri Dixit. The painter is known to be lover of films (or otherwise, how could he make such bold cinematic statements?). A close relative, residing in Dubai, said that he had seen Husain coming out of a theatre after watching Dhobi Ghat there. Husain had tried to capture the essence of Indian womanhood through a series of paintings dedicated to Madhuri Dixit, entitled “Fida”. Husain had, of course, come a long way from those difficult days when he used to sleep on the footpaths of Bombay and paint billboards.

Husain was charged with hurting the religious sentiments of the people of India because of his nude portraits of Hindu gods and goddesses. People felt perhaps that the artist had breached his artistic licence. In 2006, After Husain had completed and had a few private screenings of his third and ultimate cinematic statement, Meenaxi: A Tale of Three Cities (starring Tabu) the All- India Ulema Council complained that the Qawali song “Noor- un –ala – Noor” was blasphemous. They argued that the song contained words directly from the Quran, The Muslim religious text. Non-bailable warrant was issued to Husain after he failed to respond to summons. Husain left the country, surrendered his passport and lived abroad in self-imposed exile since 2006. He took up a Qatari citizenship, living in Dubai and spending his summers in London. The artist had always expressed his desire to return to his homeland and this is revealed in the various audio-visual and print media interviews which he gave. He died at the Royal Brompton Hospital in London and was buried in the city on June 10, 2011. It would be interesting to note that his website draws a big blank.

To quote Husain (11th July, 1969): “Those cracks that I am aware of cracks in Rembrandt whose browns burn in me, though rock-rust boots are ditched deep yet the silky sun million miles away shrills me. With those hands shivering, I hold a movie camera capturing images half-cut, unrelated to its environment. The environment becomes a stage from where the main character and the main object is totally isolated. Camera moves from one frame to another, each frame in itself is an act but the succession of frames contradicts the image. And such an image multiplied by mechanical device, emerges as a monster. The monster who flickers on everybody’s screen of retina asleep or awake. In the beginning, it did frighten the people all over but now they have fallen in love with and every night they go to bed with him.”