- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

Husain’s ‘Zameen’

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Feature

by Ratan Parimoo

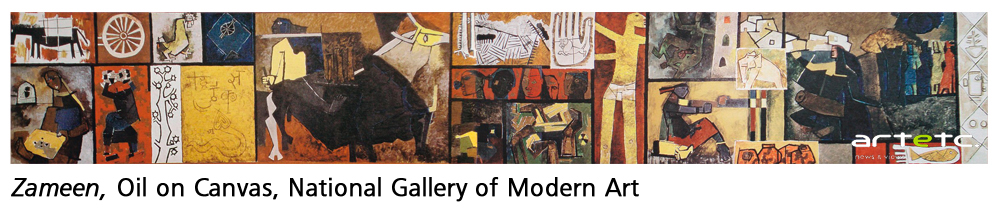

I would like to present my reading of Husain’s Zameen which received the Lalitkala Akademi’s prize in 1955. I would like a question to be kept in mind. What is in Zameen which should be objectionable to artists of 60s and critics writing in 70s about the artists of 50s?

I think Zameen is a magnum opus of Husain representing something like summing up of the first decade of his work as a painter. It is an experiment which still has relevance and validity even in the kind of thinking begun with the present decade of this century. It comprises of compartments, two dimensional forms, a whole ensemble of forms, many of which serve as symbols, emblems, pictographs of India, placed in hierarchies, occupying spaces prominently in the centre, or in the margins.

It has the format of a long continuous frieze, therefore a mural, thus it has no compositional focus associated with easel painting but horizontally oriented continuity, which also makes it revolutionary on one hand and also on the other hand reminds us about the long friezes in rock cut caves and in temple architecture, besides the painted murals in Ajanta caves. Although the Ajanta murals depict a connected continuous narrative compartment by compartment, Zameen is an ‘implied narrative’ compartment by compartment where the figure, the animals, the pictographs although like iconic characters, also stand for a story. One obvious story is the activities of the ordinary Indian masses in the villages and towns. Husain eschews naturalism for two-dimensionality and pictographic simplicity, although both the Bombay group and the earlier formulated Calcutta group wished to relegate subject matter to secondary importance. While several artists of his own generation aspiring to be modernists had to begin with the Shergilesque, from which they could not grow further, there is no Shergilesque in this major work of Husain. He has also not taken recourse to reducing the human and animal forms to utmost simplicity in bold graceful lines like in Jamini Roy’s works, which was also a solution adopted by several artists at that time. Husain was instinctively able to combine the notion of picture plane wedged into another picture plane as in the structure of synthetic phase of Cubism and also in Jain miniature painting. Perhaps the notion of bold lines was certainly an impact from Jamini Roy which counter acts against the Shergilesque simplification of volumes (Although simplification of form at that time was also known as abstraction – but I am not using this term).

Without forcing any special symbolism or metaphorical signification, we can observe that Husain’s forms have a ruggedness, a roughness, a toughness, a resilience due to these being primordial, like the motif of the churning woman, who has been doing so for ages, she is both time-worn and resilient.

I see in it an old culture as well as the perennial struggle of humanity. I see in the pair of bulls tilling the land a primeval human effort for civilization and survival. The donkey carrying a load, the wheel, the cock, the elephant in their altered sizes of scale, mother and child next to whom is a framed elephant – hoary symbol for maternity familiar from the dream of Maya Devi, Buddha’s mother, the raised hand, associated with marriage, also placed on the bodies of cattle, the foot print (again associated with Buddha, Vishnu). Husain could assemble all these because he is completely a man of Indian earth i.e. Zameen.