- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

The Market Masters

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Market Monitor

by Art Bug

It’s not a mere coincidence that the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group was formed in the same year that India gained her Independence from British rule. After all, it was through the leading lights of the founding members of this group that the world came to be acquainted with what is termed as modern Indian art. It still does.

The crux of the Progressives can be deciphered from what S H Raza, the only living member of the group of the original six said in an interview after his return to India from France, “Our ways of looking at models and compositions reflected our education, which was British. In the ’30s and ’40s there was this shift from the British way of looking at art to an Indian way, which was not just about knowledge but also informed by the senses.”

This guiding principle has been one of the main reasons of the large acceptance of the top three stars of the Progressive Artist’s Group in the world art market. Their sensibilities imbibed a sense of the ‘Indianness’ which had so far been absent in the largely folkish, miniaturist or figurative forms of the only other prominent school of art coming out of the subcontinent—namely the Bengal School, while at the same time, the Progressive artists could enter into a dialogue with the ‘other’ world through their uniquely interpreted form of expression, which had a whole lot of influences, but largely European and American. Interestingly, that is where the markets also existed.

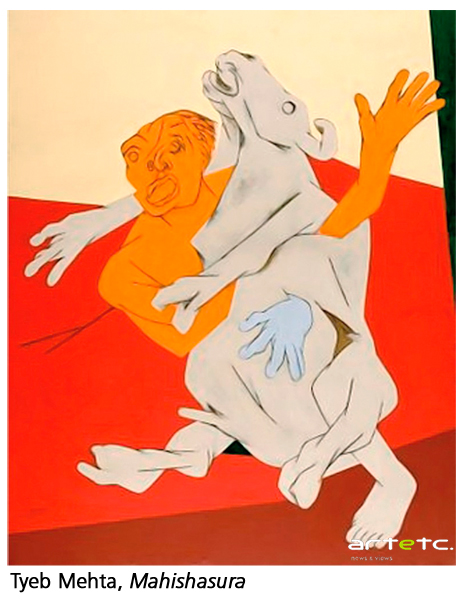

Frankly speaking, the top three of the Progressives— Husain, Souza and Raza still command the biggest chunk of the Indian art market the world over. As the Times of India in a December 8, 2011 article wrote, “Though there is no established monitor for Indian art - with the field relying mostly on independent estimates by various agencies - a majority of the experts agrees that the Big Four (Husain, Raza, Souza and Mehta) hold more than half of the total market. The market itself is valued at anywhere from $100 million to $ 400 million (roughly Rs 1000-1600 crore). This is, however, a finite market, as Husain, Souza and Mehta have passed away. Mehta, anyway, was not a prolific painter and created only about 200 canvases in his lifetime though it was his Mahishasura that had first crossed the million dollar mark when it fetched $1.54 million at a Christie's auction in September 2005. Husain and Souza were productive but the frequency with which their canvases will come into the market will depend on the collectors who hold them.”

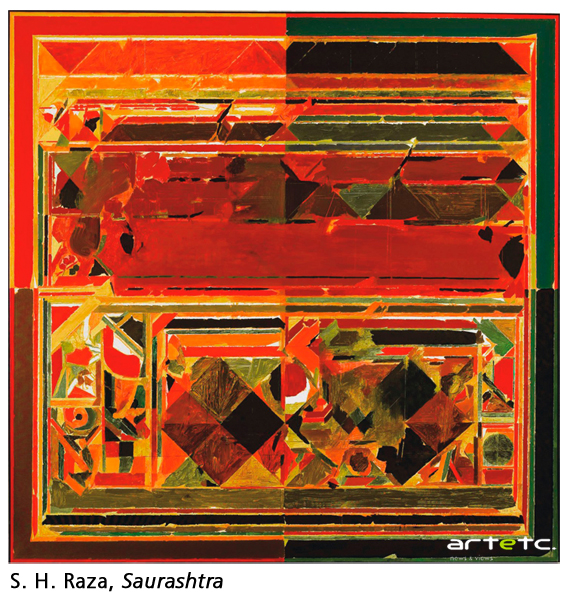

It is also to be noted that it is Raza who still holds the record for the highest price commanded by the work of an Indian artist, which was created when his Saurashtra sold for the record-setting $3.4 million at Christie’s in 2010. In fact, the New York Times in an article dealing with the Bombay Progressives agreed that, “Of the original six, it is Mr. Husain, Mr. Raza and Souza who command the highest prices at international auctions... top lots by Souza and Mr. Husain have sold in past auctions for $2.5 million and $1.6 million, respectively.”

According to a latest report by Arts Trust, which has been collated after tracking auction prices from all domestic and international auctions and market reports to give an approximate price movement of the best performing Indian artists, Raza, Husain and Souza feature among the top four Indian painters in terms of market liquidity. A close look at the graphs reveal that Raza had over US $ 15 million sold in 2010 and was the most liquid artist that year, with a lot of his paintings coming into auctions all through the year. In 2011 too, Raza initially started on a very strong note, but since July, his prices came down. Though there has been an average 20 per cent drop in his prices since then, he has managed to remain on a plateau thanks to some of his paintings selling at 2007-08 levels during the initial half of 2011.

Husain comes second in terms of liquidity. Although 2010 has been a low point for the prolific artist, his death in 2011 has made the subsequent market pretty bullish. One of the reasons may be that collectors now know that new Husain canvases will never be created and thus there is a rush to posses one of India’s most controversial and most popular artists the world over—so much so that the change in average price between 2010 and 2011 has been close to 100 per cent, in some cases almost, if not wholly reminiscent of the 2007 peak year. Incidentally, it has been Husain’s older paintings that have been fetching the high prices.

The third most liquid artist has been Souza. He went up to his highest in 2007, but with the global economic downturn, his value came down sharply. 2010 had not been a good year for Souza collectors, but 2011 told a different story, with his prices going up on an average of 100 per cent when compared to 2010 standards. However, just like Raza and Husain the second part of 2011 has also been slow for Souza.

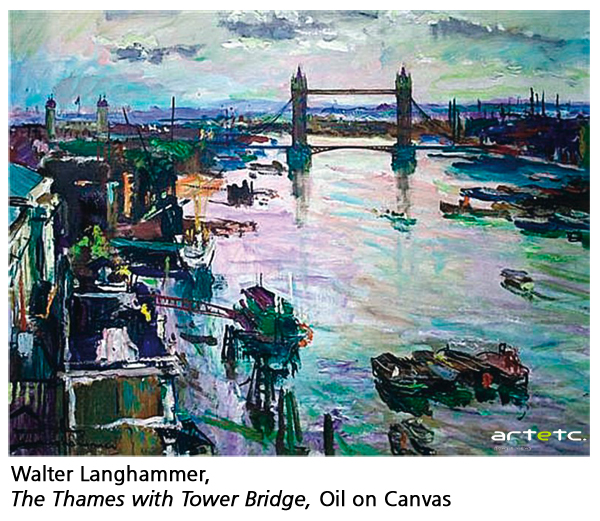

Although the top three of the founding fathers have enjoyed the cake and the cherry, what happened to the rest three? Why did they fade out eventually, hardly being able to create a dent in the international market? The New York Times article explains it precisely and honestly—“Unlike the others, Ara had no formal art training and was helped by both von Leyden (an art patron of Bombay in the forties and fifties), who paid him a small stipend, as well as by Langhammer (another art patron), who helped him hone his technique. He painted still lifes and then migrated to nudes, before spending most of his time running The Artists’ Center, a gallery for emerging artists. Gade, a longtime friend of Mr. Raza’s, trained in the sciences and is said to have discovered modern art only after joining the Progressives. Colour and landscapes were his calling cards, but he struggled to gain recognition and fell into relative obscurity. Bakre experimented with various mediums, including sculpture and wood carving, in addition to painting. After living in Britain for 24 years, he returned to a reclusive life on the coast of western India, and publicly accused some of his Progressive peers, especially Mr. Husain, of opportunism. That Ara, Gade, and Bakre did not achieve the fame of Mr. Raza, Mr. Husain and Souza is in part explained by the latter three’s prodigious output. “The mind space that Raza, Husain, Souza share is very strong,” said Dinesh Vazirani, co-founder of the online auction house Saffronart. “They are deeply entrenched in the market, and any collector of modern Indian art wants to own them.” By 1950, Mr. Raza had left for France and Souza for England. Bakre followed in 1951. The original group may have disbanded, but the Progressives continued to exist until 1956, with a younger group of artists coming together under its rubric. “Although the group faded away in 1956, the Progressives are an important punctuating point in locating the modern Indian art movement,” said Ms. (Maithili) Parekh (director) of Sotheby’s (in India). “Even today, having stood the test of time, paintings by Husain, Souza, and Raza form the core of stellar private and public collections of Indian modern art.”

Although the top three of the founding fathers have enjoyed the cake and the cherry, what happened to the rest three? Why did they fade out eventually, hardly being able to create a dent in the international market? The New York Times article explains it precisely and honestly—“Unlike the others, Ara had no formal art training and was helped by both von Leyden (an art patron of Bombay in the forties and fifties), who paid him a small stipend, as well as by Langhammer (another art patron), who helped him hone his technique. He painted still lifes and then migrated to nudes, before spending most of his time running The Artists’ Center, a gallery for emerging artists. Gade, a longtime friend of Mr. Raza’s, trained in the sciences and is said to have discovered modern art only after joining the Progressives. Colour and landscapes were his calling cards, but he struggled to gain recognition and fell into relative obscurity. Bakre experimented with various mediums, including sculpture and wood carving, in addition to painting. After living in Britain for 24 years, he returned to a reclusive life on the coast of western India, and publicly accused some of his Progressive peers, especially Mr. Husain, of opportunism. That Ara, Gade, and Bakre did not achieve the fame of Mr. Raza, Mr. Husain and Souza is in part explained by the latter three’s prodigious output. “The mind space that Raza, Husain, Souza share is very strong,” said Dinesh Vazirani, co-founder of the online auction house Saffronart. “They are deeply entrenched in the market, and any collector of modern Indian art wants to own them.” By 1950, Mr. Raza had left for France and Souza for England. Bakre followed in 1951. The original group may have disbanded, but the Progressives continued to exist until 1956, with a younger group of artists coming together under its rubric. “Although the group faded away in 1956, the Progressives are an important punctuating point in locating the modern Indian art movement,” said Ms. (Maithili) Parekh (director) of Sotheby’s (in India). “Even today, having stood the test of time, paintings by Husain, Souza, and Raza form the core of stellar private and public collections of Indian modern art.”

Thus it has been the top three that have mattered. And that actually has been the magic of the Progressive Artists’ movement in the international market. They have, since they burst into the international scene, emerged as the most sought-after Indian artists on auction floors throughout the world.