- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Feature

by Dr. Manisha Patil

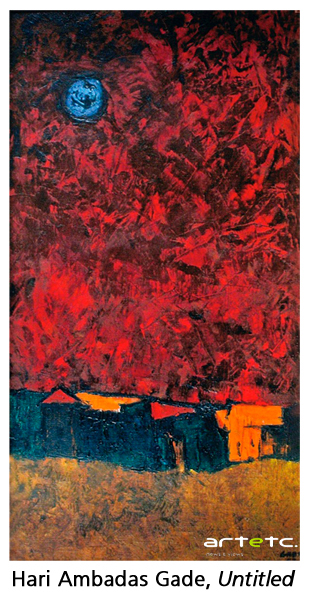

The name Hari Ambadas Gade comes with a tag- ‘Progressive Artists Group.’ It is a well recorded fact that he was one of the six founder members of the group which heralded modernism in Indian art. Of the entire Progressive who stirred up a storm on the art scene of Bombay in the late 1940’s Gade was perhaps the most reclusive figure.

The name Hari Ambadas Gade comes with a tag- ‘Progressive Artists Group.’ It is a well recorded fact that he was one of the six founder members of the group which heralded modernism in Indian art. Of the entire Progressive who stirred up a storm on the art scene of Bombay in the late 1940’s Gade was perhaps the most reclusive figure.

The pulsating city of Mumbai, Bombay of yore, saw many an aspiring artist from different corners of the country and diverse backgrounds converge here, Souza and Bakre from Goa and Konkan respectively, Ara from Hyderabad and Husain, Raza and Gade from Central India. Gade and Raza in fact briefly studied together at Nagpur School of Art prior to shifting base to Mumbai. Gade was distinguishable from the other members of his group, he was the only one armed with ‘proper’ academic qualifications, albeit in a different discipline- he was a Science graduate from the Nagpur University. His cut and dried approach to his art practice and the way he envisaged the visual world may have something to do with his engagement with scientific theories in the youth.

The pulsating city of Mumbai, Bombay of yore, saw many an aspiring artist from different corners of the country and diverse backgrounds converge here, Souza and Bakre from Goa and Konkan respectively, Ara from Hyderabad and Husain, Raza and Gade from Central India. Gade and Raza in fact briefly studied together at Nagpur School of Art prior to shifting base to Mumbai. Gade was distinguishable from the other members of his group, he was the only one armed with ‘proper’ academic qualifications, albeit in a different discipline- he was a Science graduate from the Nagpur University. His cut and dried approach to his art practice and the way he envisaged the visual world may have something to do with his engagement with scientific theories in the youth.

Born in 1917 at Talegaon in Amravati district of Maharashtra, Gade’s interest in Art appears to have been generated around the time he completed his formal education at Nagpur. ‘I was fond of drawing as a child’ the artist said, ‘but due to a compelling interest in science and mathematics, pursued my studies in this direction.’ His first job was as a lecturer at the Spencer Training College in Jabalpur , whose picturesque environs inspired him to paint his first landscapes, while he also read a bit about art techniques and became acquainted with Roger Fry’s ‘Vision and Design’.

Gade ‘s initiation into the world of painted images happened at Bapurao Athavale’s Nagpur School of Art, wherein he acquired the basic skills of drawing and spent many hours painting landscapes in the vicinity like his fellow students at the art school. Haribahu, as Gade was referred to, and Raza often went for landscapes together, recalls N.B. Dikhole, an octogenarian artist from Nagpur who was also enrolled in Athavale’s art school. In fact Raza, who was poised to move to Bombay for his further education in art is said to have egged on Gade to shift base to the city. A graduate diploma and an Art Masters from Sir. J.J. School of Art followed and Gade, like his contemporaries was geared up to learn a great deal from the turn of events in the art world.

1947 had dawned. Those were heady days on the burgeoning city’s art scene, and the Progressives, led by the fiery Souza were making their presence felt, meeting for exciting discussions at the Chetana Restaurant or The Bombay Art Society Salon. Their unenviable financial status or material discomfort was not a deterrent in the quest for a new language of art. Gade displayed his landscapes in water colours in his first solo show in Mumbai the same year, including works from his stint as a teacher in Jabalpur like Fountain Jubbalpore. The water colours follow a ‘light of touch’ style made popular by Raza and Bendre commented the art critic Rudy von Leyden, who had written encouragingly about the solo exhibitions of Souza, Raza, and Ara before the Progressive Group held their maiden show in 1949. ‘Gade’s paintings possessed the intrinsic virtues required to keep enjoyment alive ‘were the heartening comments of von Leyden. These ‘intrinsic virtues’ would spur Gade to pour his energies to painting full time, and be around as exciting things happened all around him in the growing city.

After tasting his first bout of success, Gade moved on to other mediums, notably gouache and oil colour. A compulsive traveler, his visits to diverse locations guided his painterly eye to ‘select’ subjects which were after his heart. The artist predilection for the raw and the rugged -hills, valleys and river basins, sleepy little villages with snaking alleys would eventually come to characterize his signature style. The historic town of Omkareshwar, perched on the banks of the Narmada, was one of his early inspirations, as he delightfully picked out locations in and about the town. He has waxed eloquent about the imagery and colours of the place. ‘‘The landscape thrilled me and I was moved as never before. ‘’ The phase was indeed a momentous one in the young artist’s life. His endeavours won appreciation by the way of a silver medal at the Bombay Art Society exhibition in 1948, around the same time that he joined the Progressive Artists Group.

Omkareshwar was a revelation in more ways than one- it saw the young artist cast away the last vestiges of the representational. He talks about how the imagery of the place was ‘unbelievably different’ and ‘colours strange and unique’. Apprehensions about image making were finally overcome and Gade had in all probability arrived at the ‘significant form’ which Raza talked about. To put in Gade’s words ‘the disparity of what he felt and what he saw was a significant experience’ and this was to become the guiding light in his art practice. Gade’s long standing engagement with colour had begun. The artist’s exposure to modernism owes much to the long discussions held by the young members of the Progressive Artists Group, and the Expressionist approach to colour is likely to have been influenced by the works of Walter Langhammer, the Austrian expatriate and art director at the Times of India who patronized the Progressives. There was also a great deal to imbibe from the bright colour schemes and broad sweeps of the brush of the Indore painters.

Says von Leyden about Moonlight over Omkareshwar- ‘It is a compact, well constructed picture, the blue-green shades of which are reminiscent of Cezanne in their architectural solidity.’ The early fifties also saw Gade interpret landscapes of Udaipur and Nasik in the new pictorial idiom. A family trip around the same time to Kashmir proved to be fruitful – the valley, with its breathtaking views of mountains, roads and steep, winding houses with sloping roofs engaged the artist who was in search of form and colour. The Kashmir series is particularly noteworthy for the emotive use of colour. As an art critic has noted ‘he has a good understanding of the emotional value of colours and likes to work up by means of skilful colouring at higher pitch than the subject of his paintings.’ This passion for the mountains continued till his late years- as observed in yet another series of paintings based on a trip to Himachal Pradesh in the early 1990’s.

Gade’s identity as an artist lies in his innumerable paintings on houses and streets, mostly from a semi urban milieu, and painted mostly from the mid fifties through the sixties. As a youth painting landscapes he had always shown a preference for choosing high vantage points and unusual eye levels. This fascination for seeking an architectonic alternative as formal means may have been further triggered by his two decade stay in New Delhi from 1957 onwards where in addition to his teaching job at the Central Institute of Education, Gade was visiting faculty at the College of Architecture, where he taught Art History. The houses were reduced to cubical units of coloured planes defined by dark lines of varying thickness. As art historian Nalini Bhagwat observes ‘this dark line around the forms is characteristic of the paintings of Gade, Husain, Ara as also prominent in Souza’.

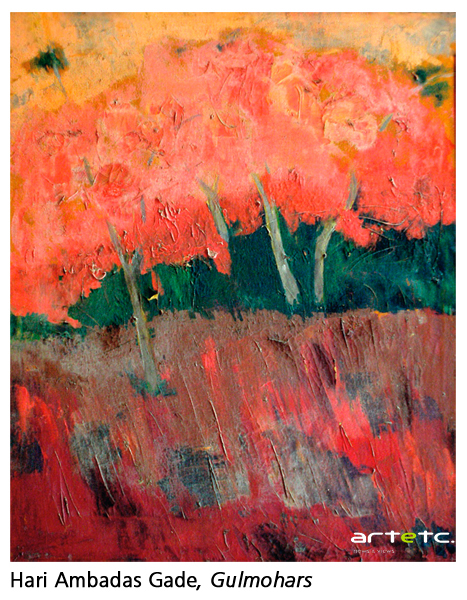

As for colour, Gade’s strength as a colourist comes across even in the landscapes of the late forties where the artist employs unusual chromatic harmonies often with dramatic contrasts. With time the palette turned richer, more luminescent, almost jewel like. The colours were loaded thickly in rapid brushstrokes and layered to create mysterious recesses. His mature works compel the viewer to look at them repeatedly, for every time they yield a new meaning. Gade himself was non committal when quizzed about what he wanted to convey. ‘I wanted to say precisely what you experience through my work’ would be his simple answer. His communion with nature was absolute, and his peaceful world was rarely interrupted by the hustle bustle of day to day movements. When he did introduce the occasional human figure or an animal against the backdrop of the hutments or the river fronts, it was more a contrived part of the pictorial scheme. Life went on, but there was rarely a burst of activity that spilled out of the canvas. For the artist it was enough to observe it pass through the dimly lit slits of the windows and doorways.

Gade seldom focused on urban life, except for the time when he painted slum dwellings, preferring smaller, nondescript towns, despite having lived his entire adult years divided between two cities, Bombay and New Delhi. Perhaps the quiet of these places let him be himself, allowed him physical and mental space to think and perceive the physical world as he wished to. Often questioned about his ideologies Gade came up with candidly simple replies - ‘I paint what I feel’.

Though less well known than his landscapes, Gade was equally fond of painting still life. His still lifes are simple and uncluttered, with objects picked up at random, stripped to their bare essentials, observed from different viewpoints and painted in broad, sweeping strokes of non-representational colours. Paintings in this genre stand out by their bold, expressive use of line and heavily textured surfaces. He was partial to flower studies, as works such as Gulmohar in Mrs. Clark’s garden , painted in 1950’s or the later painting of Gulmohars done en route to Belgaum, suggest. For a person whose roots were in the hinterland of Maharashtra, he was conversant with the many rituals and religious practices from the rural belt. A small but remarkable painting with a rare subject– the Rathasaptami festival is characteristically in his style. Painted in the mid fifties, the ritual diagram is shown by the red orb of the sun god who rides a chariot driven by seven horses. The densely textured areas and the jagged black lines unmistakably remind one of the formal language employed by the Progressives in this phase.

Though less well known than his landscapes, Gade was equally fond of painting still life. His still lifes are simple and uncluttered, with objects picked up at random, stripped to their bare essentials, observed from different viewpoints and painted in broad, sweeping strokes of non-representational colours. Paintings in this genre stand out by their bold, expressive use of line and heavily textured surfaces. He was partial to flower studies, as works such as Gulmohar in Mrs. Clark’s garden , painted in 1950’s or the later painting of Gulmohars done en route to Belgaum, suggest. For a person whose roots were in the hinterland of Maharashtra, he was conversant with the many rituals and religious practices from the rural belt. A small but remarkable painting with a rare subject– the Rathasaptami festival is characteristically in his style. Painted in the mid fifties, the ritual diagram is shown by the red orb of the sun god who rides a chariot driven by seven horses. The densely textured areas and the jagged black lines unmistakably remind one of the formal language employed by the Progressives in this phase.

‘Today we paint with absolute freedom for contents and techniques almost anarchic, save that we are governed by only one or two elemental and eternal laws, of aesthetic order, plastic co ordination and colour composition’ announced the Progressives in the foreword of the catalogue of their show in 1949. The first few years of the Progressives were eventful, the mood upbeat.

Souza was the undisputed leader and spokesperson who made hard hitting statements, while the remaining five of the group spoke little, least of all Gade. The Progressives were conversant with the works of their contemporaries, the Calcutta group who’d exhibited in Bombay in the late forties. It was followed by a joint exhibition of both groups in Calcutta in 1950, when Gade himself traveled to the city along with the Progressive artists’ paintings. By the mid nineteen fifties, the Progressive group had already disbanded, with Souza, Raza and Bakre having left the country, new entrants were welcomed into the fold, and Gade took charge as the group’s secretary. The artist was himself now unsure about his future. Sustaining a family on art was not a very viable idea in the Bombay of the fifties. On the threshold of age forty, Gade gave up the uncertainties of a freelancer’s life for security and moved to New Delhi. At the Central Institute of Education, he taught the subject of Art Education. In his two decade career in the country’s capital devoted to teaching, Gade never gave up painting. Closely associated with the Lalit Kala Akademi, Gade, along with B.C. Sanyal was a part of the group that represented India in the first ever exhibition of ancient paintings, sculptures and contemporary artworks held in December1955.when he traveled to Eastern Europe, visiting Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria and Moscow. His individual works had been showcased earlier in 1949 at the Salon de Mai in Paris, followed by an exhibition at Stanford University. In 1954 Gade was invited to participate in the Venice Biennale. His painting was awarded a gold medal at the Bombay Art Society exhibition in 1957.

As the years rolled by, the obsession with the pictorial form took precedence over everything else. The angularities of the cubical houses and the sinuous curves of the winding roads dissolved to give way to rectangular blocks of brilliant crimsons, deep blues, emeralds and tangerines embedded in a matrix of textures. Even in Gade’s abstractions there lies a precision, an element of calculation, he appears to tread his path cautiously. He has quietly asserted that his paintings are not devoid of emotions, as many came forth with the opinion that they were nothing beyond formal exercises. Gade believes that he owes much to emotion as a colourist. ‘I paint passionately, leaving the intellectual problems behind’ is how he sums up his work.

He had few but lifelong friends and almost never courted controversies. Quiet and peace loving, his scientific bent of mind and inclination towards technique made him hone his skills in other areas such as masonry, carpentry, pottery and batik design. Post his retirement from the civil job in New Delhi, Gade returned to Mumbai to settle in suburban Chembur. He continued to travel and paint well after that but somewhere down the line, the vitality of his earlier style was lost. Sometimes the magic of the Kashmir phase was recreated in paintings from such as ‘Darjeeling’ of 1982 with its Noldesque riot of colours. The burst of energy and the passionate engagement with his medium that characterized his best works from the nineteen fifties and sixties gradually became less and less, there were no new concerns occupying the artist. He had in a way fulfilled his mission as a painter.

Gade’s last painting was a still life painted in 2000, a year prior to his death. His family remembers how the aging artist had this sudden urge to paint the orchids in a vase in the drawing room. The work exhibited and sold at Bombay Art Society’s annual show, was donated as charity by the veteran artist.

Gade will be remembered as one of the first abstract expressionists in the country, a trend which was to be elevated to unprecedented heights by the likes of Ram Kumar and Gaitonde. In his own subdued manner, Gade stood for the ideals and ambitions of the Progressive Group. From his youth to the end of his life, his bond with nature remained inseparable. Nature was his muse, a sustaining force that shaped his creativity. As Rudy von Leyden succinctly put it’ his starting point is nature, his point of arrival is Gade’.