- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Review

by Anuradha Ghosh

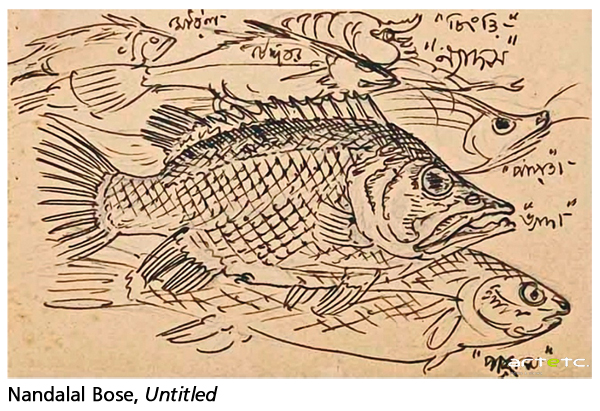

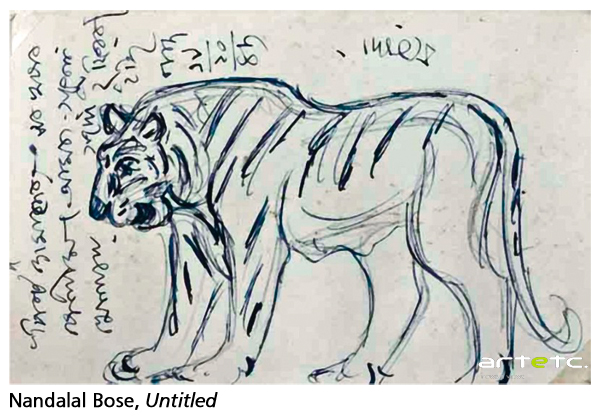

Kolkata. It’s a rare exhibition that offers viewers such an overwhelming,almost overpowering, sense of intimacy. Intimacy, in all its forms and ramifications, which includes an invitation to approach and even eavesdrop onto private exchanges: for this remarkable show, Postcards of Nandalal Bose hovers around that indeterminate area between the private and the public, the intimate message and the open iteration, a poise that makes for the singularity of the show. For what we are looking at are real-life letters, carried by post, with the text side unrevealed in most cases. Yet the sketches that face us are frequently connected to the unseen text, bound therefore by a narration/illustration referentiality. The curator of this show at Akar Prakar, Debdutta Gupta (who owes us an entirely deserved round of thanks for this very special effort) insists that these exhibits ‘can also be seen as part of the miniature corpus’. This is justifiable not only because the actual, physical dimensions of the postcards- that is, the smallness of the support- neatly agrees with the conceptual requirements of the genre. I had always felt that the miniature form frequently requires, and actively operates on, a deeper measure of intimacy on the part of the viewers- probably hinging upon the simple fact that one needs to come closer to the artwork in order to view it properly. In this particular case, this circle of physical proximity is also overwhelmingly underlined by a very real sense of privileging: the chance of being witness to a series of intimate, private interactions.

Kolkata. It’s a rare exhibition that offers viewers such an overwhelming,almost overpowering, sense of intimacy. Intimacy, in all its forms and ramifications, which includes an invitation to approach and even eavesdrop onto private exchanges: for this remarkable show, Postcards of Nandalal Bose hovers around that indeterminate area between the private and the public, the intimate message and the open iteration, a poise that makes for the singularity of the show. For what we are looking at are real-life letters, carried by post, with the text side unrevealed in most cases. Yet the sketches that face us are frequently connected to the unseen text, bound therefore by a narration/illustration referentiality. The curator of this show at Akar Prakar, Debdutta Gupta (who owes us an entirely deserved round of thanks for this very special effort) insists that these exhibits ‘can also be seen as part of the miniature corpus’. This is justifiable not only because the actual, physical dimensions of the postcards- that is, the smallness of the support- neatly agrees with the conceptual requirements of the genre. I had always felt that the miniature form frequently requires, and actively operates on, a deeper measure of intimacy on the part of the viewers- probably hinging upon the simple fact that one needs to come closer to the artwork in order to view it properly. In this particular case, this circle of physical proximity is also overwhelmingly underlined by a very real sense of privileging: the chance of being witness to a series of intimate, private interactions.

To rashly attempt an one-liner: the sketches and drawings attempt to capture lived life, along with its myriad contexts and references. The rural and the subaltern form a recurrent thematic pattern (I would have loved to resist the mention of these theoretical categories, as their present critical import may in fact be misleading and erroneous in case of Nandalal: for him the portrayal of the marginal as a subject did not seem to carry the undernote of a reverse privileging). The fisherman, the sweetmeat peddler, the carpenter and many such figures are captured in simple rhythmic lines, central to the design of life that he fabricates- each ensconced in his own profession, each with his own social space that is very clearly non-judgemental. In fact I have noted in these drawings a very strong tendency towards documentation. The meticulous eye for detail, coupled with the ever-alert sensibility of a legendary art teacher created works which could well be studied for their educative value alone. What is immensely interesting is that, his encounters with any object that is unfamiliar, even unusual, seem to have invariably resulted in attempts to capture and pictorially describe its shape, size and functionality. There’s this postcard which minutely describes the working of a ‘latakhamba’, which is a lever used in parts of Bihar to draw underground water, the layers there frequently lying too deep down for normal access. What is remarkable about this drawing is the artist’s delight in detail- the mechanism is captured on the postcard with perfect precision, while the insertion of text labels lends the work the countenance of a scientific diagram. One can hardly miss Nandalal’s unbridled, almost child-like wonder at this homespun utility machine. In a sense, Nandalal captures the social culture of a given region with limited lines, on a limited canvas, but with a touch that enlivens the work with the flavor of locality. In one way, they are travelogues then- this, and the other postcards recording his stay at Hazaribagh, written to his son-in-law Santosh Kumar Bhanja- visuals supplementing, and oftener than not, even surmounting text, communicating one’s situatedness through a different set of alphabets.

Situatedness, though, could be a complex matter to unravel, and communicating it would be an even more trying task, something that had always been one of the most ingrained challenges of creativity. It is this interpermeation between the self and the surroundings that defines a cultural moment, the material of history and of art, and this series of postcards offers an invaluable scope to observe and study the workings of a syncretic cultural vision. Since we are dealing with artworks which are chiefly letters, the question of communication gains a natural primacy. If we take the example of the series of postcards sent from places as diverse as the Bagh caves, Darjeeling, and Benaras, we shall see how Nandalal had let his surroundings transcribe his moment of being. In a postcard sent from ‘Chandmari, Darjeeling’, precise strokes describe the hilly terrain, the lush vegetation on the slopes, and the cloudy sky, all at once. But it is really the foregrounded figure rotating the prayer wheel that fixes the otherwise undifferentiated landscape to a solid local mooring. Could we call these ‘cultural landscapes’, then, using the term rather tentatively? This reminds me of an immensely significant point he made in Drishti O Srishti: speaking about the co-presence of nature and human/living figures in landscapes, Nandalal maintained that the principal focus of the work should receive a subdued treatment (that is, if the chief concern is nature, it is the included figure that should be treated with closer attention and meticulous detailing- and vice versa). Here he is very clearly talking about an oblique way of seeing, of defining a subject not by itself, but by its complement. Nandalal also clearly states that it is the living being transposed within a landscape that embodies the self of the painter in an artwork, and enthuses it with life. I had always felt that Nandalal’s figures-in-landscapes, apart from serving the very significant purpose of animating nature, also mediate as instruments of empathy for the viewer. And there are quite a few exhibits in the show that amply illustrates this.

Situatedness, though, could be a complex matter to unravel, and communicating it would be an even more trying task, something that had always been one of the most ingrained challenges of creativity. It is this interpermeation between the self and the surroundings that defines a cultural moment, the material of history and of art, and this series of postcards offers an invaluable scope to observe and study the workings of a syncretic cultural vision. Since we are dealing with artworks which are chiefly letters, the question of communication gains a natural primacy. If we take the example of the series of postcards sent from places as diverse as the Bagh caves, Darjeeling, and Benaras, we shall see how Nandalal had let his surroundings transcribe his moment of being. In a postcard sent from ‘Chandmari, Darjeeling’, precise strokes describe the hilly terrain, the lush vegetation on the slopes, and the cloudy sky, all at once. But it is really the foregrounded figure rotating the prayer wheel that fixes the otherwise undifferentiated landscape to a solid local mooring. Could we call these ‘cultural landscapes’, then, using the term rather tentatively? This reminds me of an immensely significant point he made in Drishti O Srishti: speaking about the co-presence of nature and human/living figures in landscapes, Nandalal maintained that the principal focus of the work should receive a subdued treatment (that is, if the chief concern is nature, it is the included figure that should be treated with closer attention and meticulous detailing- and vice versa). Here he is very clearly talking about an oblique way of seeing, of defining a subject not by itself, but by its complement. Nandalal also clearly states that it is the living being transposed within a landscape that embodies the self of the painter in an artwork, and enthuses it with life. I had always felt that Nandalal’s figures-in-landscapes, apart from serving the very significant purpose of animating nature, also mediate as instruments of empathy for the viewer. And there are quite a few exhibits in the show that amply illustrates this.

Apart from the human figures, Nandalal’s drawings of animals, birds, fishes and even insects deserve special attention. Often they are parts of a landscape, but there are quite a few works where these creatures are captured for their own sake- with an attentive eye to detail- often reminding us of natural history drawings. There’s this work which depicts no less than six different species of fishes, with familiar names- we must keep in mind that most of these non-exotic fishes used to be quite inexpensive then, and thus must have been included in the day-to-day diet of the average Bengali. Familiarity, then, is the keyword here. Nandalal, in this meticulous study, is also trying to carefully differentiate between the appearances of these fishes almost with the ardent eye of a dedicated student; the educative intention can hardly be missed here. This work also indicates how the film of unfamiliarity often leads us to overlook the wonder of details.

Apart from sketches, the exhibits include a number of pen and ink drawings, a woodcut and a linocut. Nandalal’s experiments with printmaking involved a technique of simplification, rejecting details in order to capture the essential form in bold and untentative lines. For many of us, these specific works also initiate a pleasant jolt of memory, as we are reminded of the linocuts of Nandalal that were used for Sahaj Paath illustrations, those well-loved prints that played such a significant role in shaping our visual imagination during early childhood (a similar nostalgic vein accompanies Nandalal’s watercolour illustrations of Gnanadanandini Devi’s Tak Duma Dum Dum). In some of his pen and ink works, we witness an interesting use of calligraphic lines: the expressionistic undernote of such lines are bridled with designal control, this duality gaining in significance especially in view of the given limits that the smallness of the support has to offer. In fact what I found primarily noteworthy in the specific context of this exhibition is the magic of containment. It hardly takes much effort to appreciate the mastery that goes behind the achievement of a sense of completeness within a pre-allotted, tiny space. I would like to refer to a postcard which illustrates the admirable use of wash technique, depicting a crow and a rat (this work gains in emotional significance when we are reminded that this postcard was sent to Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal’s mentor in wash technique, at the Patharpuri Tagore House in Puri).

Apart from sketches, the exhibits include a number of pen and ink drawings, a woodcut and a linocut. Nandalal’s experiments with printmaking involved a technique of simplification, rejecting details in order to capture the essential form in bold and untentative lines. For many of us, these specific works also initiate a pleasant jolt of memory, as we are reminded of the linocuts of Nandalal that were used for Sahaj Paath illustrations, those well-loved prints that played such a significant role in shaping our visual imagination during early childhood (a similar nostalgic vein accompanies Nandalal’s watercolour illustrations of Gnanadanandini Devi’s Tak Duma Dum Dum). In some of his pen and ink works, we witness an interesting use of calligraphic lines: the expressionistic undernote of such lines are bridled with designal control, this duality gaining in significance especially in view of the given limits that the smallness of the support has to offer. In fact what I found primarily noteworthy in the specific context of this exhibition is the magic of containment. It hardly takes much effort to appreciate the mastery that goes behind the achievement of a sense of completeness within a pre-allotted, tiny space. I would like to refer to a postcard which illustrates the admirable use of wash technique, depicting a crow and a rat (this work gains in emotional significance when we are reminded that this postcard was sent to Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal’s mentor in wash technique, at the Patharpuri Tagore House in Puri).

There is an entirely different series of works in the show- the collages- that hint at another journey, another distinct way of negotiating with referentiality. Whereas a study begins with a fixed object which is then subjectivised, and often embellished with atmosphere, these works frequently began with certain incidental forms. Pieces of paper (coarse brown paper in most of the works) were torn out, pasted on the support, lines were drawn to add recognizability and context. The creative play involved here, the inherent delight in understanding the essential form in the piece of paper, and consequently, seeking a referential frame for the abstract shape, introduces the viewers to the actual, palpable process of creative translation of a true master.

Intimacy means closeness, intimacy also implies a sharing of space. My experience with this show was a revelation in a very real sense: here was a perfect illustration of the way in which a significant show opens up a shared space between the artist and the viewer, thus making possible multiple lines of communication that are almost instinctive.