- Publisher’s Note

- Editorial

- Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview

- S. H. Raza: The Modern

- Ara: The Uncommon Commoner

- Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

- M.F. Husain: An Iconoclastic Icon

- Husain’s ‘Zameen’

- Life and Art of Sadanand Bakre

- Hari Ambadas Gade: Relocating the Silent Alleys

- Mysticism Yearning for the Absolute

- Modernist Art from India at Rubin Museum of Art, New York

- Traditional Art from India at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Nandan Mela 2011: A Fair with Flair

- India's First Online Auction of Antiquities

- The Market Masters

- Markets May Plunge and the Rich May Flock To Art

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Julian Beever: Morphing Reality With Chalk Asthetics

- Eyes on Life: Reviewing Satish Gujral’s Recent Drawings

- Exploring Intimacy: Postcards of Nandalal Bose

- Irony as Form

- Strange Paradise

- Eyeball Massage: Pipilotti Rist

- René Lalique: A Genius of French Decorative Art

- The Milwaukee Art Museum – Poetry in Motion

- 9 Bäumleingasse

- Art Events Kolkata: November – December 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dais

- Tacita Dean at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London

- Preview: January, 2012 – February, 2012

- In the News: December 2011

ART news & views

Art of Francis Newton Souza:A Study in Psycho-Analytical Approach

Issue No: 24 Month: 1 Year: 2012

Feature

by Ratan Parimoo

This essay is written by a painter art historian who has been keeping an ‘eye’ on Souza (1924-2002) since his own student days during the 1950s at Baroda. It is a shorter version of a comprehensive critical essay I worked on a year after his death in March 2002. With Souza’s completion of his earthly existence there is the need to have a fresh look at his entire oeuvre including writings, since at one stage he was also extolled as a promising journalist and art thinker. I wish to float two ideas at the outset. One that we can better understand his creative out-put from the psycho-analytical angle, i.e. classifying his personality as schizotypal. The other is if we can apply the notion which John Berger had formulated for Picasso: ‘Success and Failure of Francis Newton Souza’, despite of his extraordinary creativity.

This essay is written by a painter art historian who has been keeping an ‘eye’ on Souza (1924-2002) since his own student days during the 1950s at Baroda. It is a shorter version of a comprehensive critical essay I worked on a year after his death in March 2002. With Souza’s completion of his earthly existence there is the need to have a fresh look at his entire oeuvre including writings, since at one stage he was also extolled as a promising journalist and art thinker. I wish to float two ideas at the outset. One that we can better understand his creative out-put from the psycho-analytical angle, i.e. classifying his personality as schizotypal. The other is if we can apply the notion which John Berger had formulated for Picasso: ‘Success and Failure of Francis Newton Souza’, despite of his extraordinary creativity.

In 1948, as a youth of 24, Souza had painted his self portrait in complete nudity, which was probably the reason why the exhibition in which it was displayed had to be closed ostensibly for obscenity. It was one of the series of mischievous events we know from his early autobiography which included rustication from school for drawing obscene graffiti in the school premises, as well as expulsion from the J.J. School of Art of Bombay, for having slapped one of his teachers on not being allowed to shout nationalist slogans. The consistent series of self-portraits spread throughout his work from his youth to old age as well as the nude self-portrait, interestingly remind us of the similar naked figure painted by the German Renaissance painter, Albrecht Durer, (late 15th and early 16th century) which is among his several direct or indirect self portraits. On the basis of such intense interest in oneself, Erwin Panofsky had linked Albrecht Durer with the psychological state of ‘Meloncholia’, conceptualizing that such a personality also possesses extraordinary genius as well as creativity. This feature of creative genius, that is interest in oneself, has been diagnosed by Sigmund Freud as ‘narcissism’ in the psychoanalytical parlance. That Souza had written his autobiography at the young age of 35 and recorded many childhood memories is also a narcissistic trait. These autobiographical notes smack of egotism, self love, introverted pessimistic personality portraying himself as some kind of tortured soul. The personally recorded childhood memories are valued by psychoanalysts for offering leads into the mind of a diagnosed schizophrenic and even a highly creative genius. Souza had spent his childhood in relative poverty under the care of his mother having lost his father soon after his birth. There is no doubt that he was aware of Oedipus complex in the manner he linked his own birth with his father’s death in his autobiographical writings. Even the admiration for his mother has been acknowledged. The strict Roman Catholic priestly control on social life of Christian community had provided yet another factor for Souza’s bitterness towards society.

In his classic psychoanalytic study of Leonardo da Vinci, Freud has played up the phenomenon of absence of father in Leonardo as a child. Freud derived certain hypotheses out of such a case which I find relevant for the manifestation of hidden mental processes in Souza. Souza’s fatherless childhood, resulting in narcissistic orientations and self-absorption, fits in with that conceptualized by the Indian psychoanalyst, Sudhir Kakar, according to whom, the ambiguous role of the father in Indian childhood is yet another factor that attributes to the narcissistic vulnerability of Indian men. I am adopting the term ‘schizo-tyal’, which psychoanalysts have coined to distinguish between persons whose abnormal symptoms require psychiatrist’s attention (that is schizophrenia) and those persons who reveal split personality traits, but who are other-wise near normal. It is such persons who at one extreme go for brash and shocking behavior, transgressing social norms and on the other extreme are highly creative and geniuses in the fields of arts, literature and scientific inventions.

Now that Souza has completed his full life, the consistent painting of self-portraits must be considered as a significant chunk of his total work just as these are in the oeuvre of introverted narcissistic painters, Rembrandt as well as Vincent Van Gogh (both painters of Holland during 17th and 19th Century). To study Souza’s process of evolving his style and typical approach to ‘distortion’ at the level of heads and faces is also to understand his approach to the whole human figure as well as pictorial compositions.

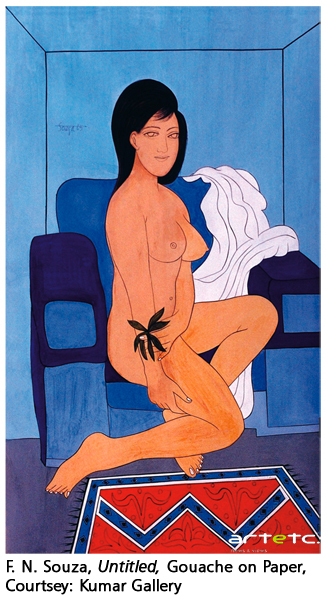

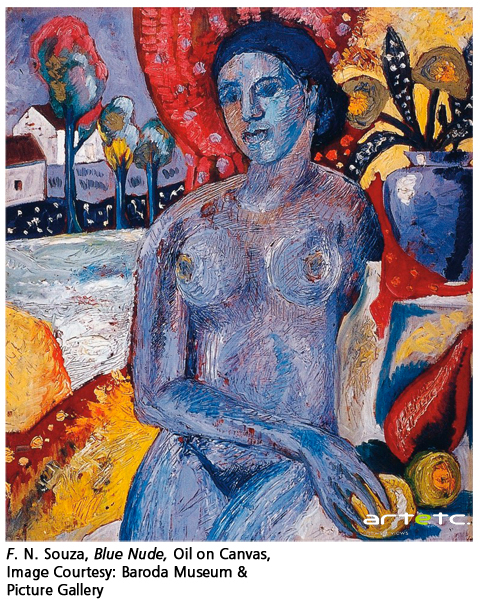

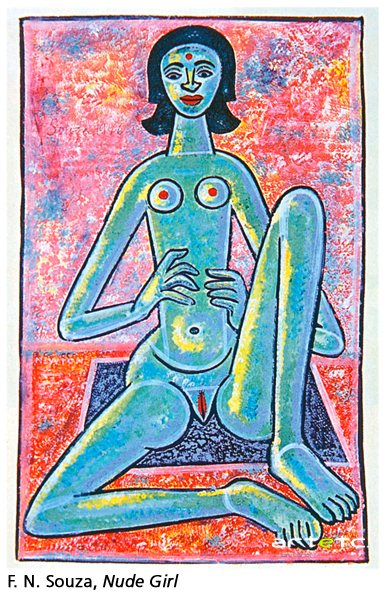

Nudes and Sexuality

(We have already covered Souza’s early phase in my ‘over-view’ article). Female nudes constitute a major repertoire of Souza’s work even from his student days. His exceptional mastery of the female form makes him a unique painter among his contemporaries and must be now considered much more than exercises in attracting attention as well as buyers. He had grown into an obsessive and compulsive painter of the female nudes which phenomenon can now be interpreted in Freudian as well as Feminist analyses. It has been observed that among the 20th century artists, painting of nudes and erotic imagery became an important weapon in the battle for modernism. Shocking the onlookers was among the strategies to assert their individuality and freedom. This way very much the case with Souza, who had already projected his bravado by depicting the nude in stark frontal view (in 1946). Very early he painted embracing couples based on photographs from the famous Khajuraho temples, establishing that he derived the buxom sensuous female form, from his observation of Indian erotic sculpture.

The manner in which the Nude Seated on Chair has been depicted in a series of variations by Souza is very instructive reflecting both his painterly ingenuity as well as his sexuality. With this favourite motif of Matisse as a usual model’s pose, Souza has taken liberties with the position of legs, first hesitatingly and subsequently unabashedly, to fit with Freudian description of the voyeuristic tendency, which we can observe in his drawing Nude on Chair, dated 1947. Subsequently the on-looker’s eye level is adjusted in such a manner so that the sexual organ of the nude, seated with outstretched knee, is directly face to face the onlooker’s gaze as in the drawings dated 1957 and 1960, and in a painted version of 1962. Even such bold variations Souza has done with his adaptations taken from the reclining nude compositions of his favorite Italian Renaissance painter, Titian. (A painting dated 1961 is based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino and a painting dated 1962 is based on Danae).

The manner in which the Nude Seated on Chair has been depicted in a series of variations by Souza is very instructive reflecting both his painterly ingenuity as well as his sexuality. With this favourite motif of Matisse as a usual model’s pose, Souza has taken liberties with the position of legs, first hesitatingly and subsequently unabashedly, to fit with Freudian description of the voyeuristic tendency, which we can observe in his drawing Nude on Chair, dated 1947. Subsequently the on-looker’s eye level is adjusted in such a manner so that the sexual organ of the nude, seated with outstretched knee, is directly face to face the onlooker’s gaze as in the drawings dated 1957 and 1960, and in a painted version of 1962. Even such bold variations Souza has done with his adaptations taken from the reclining nude compositions of his favorite Italian Renaissance painter, Titian. (A painting dated 1961 is based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino and a painting dated 1962 is based on Danae).

The insatiable voyeurist in Souza prompted him to go to the extreme limits of the postures that can be visualized in nude from behind (painted 1988). In this context the unabashed exposure provided to the female organ from the back view of the derrier pushed toward the view, can be expected only from Souza’s creative energy. To further heighten the sexuality of the imagery, he depicts two men on either side of the nude eagerly waiting for their turn. The feminist art historian, Carol Duncan, has observed that in the depiction of the nude is reflected the male artists personal masculinity and domination over the female. It represents the uninhibited sexual appetite of the artist. It is for him that these women disrobe and recline, thus willful assertive presence of the artist is too obvious. This assertion is very true of Souza who has left us in no doubt about his consistent interest in women.

A number of nude drawings and paintings around 1960 could be associated with a particular woman, same body, face and enchanting but vulnerable expression. Her long limbs and pliable body give her posture a peculiar captivating attention whether seated or standing, which the artist had caressed and known intimately. Quite appropriately Souza was capable of evoking a tenderness through adjusting the quality of line and configuration for depicting the young mother holding her newly born child. Probably the same model of the above nude paintings has posed for it and Souza has drawn it with utmost delicacy to bring-out the freshness of the motherhood in the woman and the fragility of the newly born infant. The ambiance created by the mother’s expression and the care with which she holds the child close to her as if showing it off to her lover: ‘look at the flower of our love.’

Another frequent figure type emerging in Souza’s nude drawing and paintings has heavy and buxom features. In a painting dated 1965 her seductive splendorous body is posed amidst an interesting color/space structure competing with Matisse’s paintings. It is related to a remarkable line drawing of the same large-breasted woman drawn from the side view in an innovative posture. In a 1974 titillating line drawing continues his imagery exaggerating her large breasts. We presume these two women had provided Souza with his version of the bewitching ‘femme-fatale’ imagery. Nonetheless, we could make a generalized statement that a variety of women have posed for many of his nude paintings until his old age. Undoubtedly it is the presence of the sitter which could have facilitated a fine quality of direct outline, wirery and incisive in a number of provocative nude drawings. Alongside the buxom but yielding women possessed with inviting quality, Souza has also painted the nude with repelling quality. Invariably these are painted in dark tonalities with prominently delineated private parts. These are referred to as black nudes or ‘ebony’ nudes. A sort of reverse process of painting has been devised, the details are drawn in white lines over the black naked female figure. In some paintings of this imagery the dark tonality of paint, both in the entire nude body as well as the spaces around it, are treated in nuances, of somber tones as well as texturing with brushwork and thick/thin paint layers, almost with the amazing sensitivity of a musician. In a painting the standing nude, which we may term as ‘persona’, is represented with the ‘shadow’ cast by her on the wall just behind her. The dark blue of the shadow as well as the aura-like pinkish outline around both the ‘bodies’ imparts a visual ambiguity of another person intertwined with the nude from behind her back.

Another frequent figure type emerging in Souza’s nude drawing and paintings has heavy and buxom features. In a painting dated 1965 her seductive splendorous body is posed amidst an interesting color/space structure competing with Matisse’s paintings. It is related to a remarkable line drawing of the same large-breasted woman drawn from the side view in an innovative posture. In a 1974 titillating line drawing continues his imagery exaggerating her large breasts. We presume these two women had provided Souza with his version of the bewitching ‘femme-fatale’ imagery. Nonetheless, we could make a generalized statement that a variety of women have posed for many of his nude paintings until his old age. Undoubtedly it is the presence of the sitter which could have facilitated a fine quality of direct outline, wirery and incisive in a number of provocative nude drawings. Alongside the buxom but yielding women possessed with inviting quality, Souza has also painted the nude with repelling quality. Invariably these are painted in dark tonalities with prominently delineated private parts. These are referred to as black nudes or ‘ebony’ nudes. A sort of reverse process of painting has been devised, the details are drawn in white lines over the black naked female figure. In some paintings of this imagery the dark tonality of paint, both in the entire nude body as well as the spaces around it, are treated in nuances, of somber tones as well as texturing with brushwork and thick/thin paint layers, almost with the amazing sensitivity of a musician. In a painting the standing nude, which we may term as ‘persona’, is represented with the ‘shadow’ cast by her on the wall just behind her. The dark blue of the shadow as well as the aura-like pinkish outline around both the ‘bodies’ imparts a visual ambiguity of another person intertwined with the nude from behind her back.

Psychoanalysts have drawn attention to unconscious anxieties in the male vis-à-vis the female which is termed as castration anxiety, the fear of loss of penis. The dark female nude of Souza signifies this fear. i.e. it will devour the male penis. The devouring female is a take-off from the ‘femme-fatale’ imagery of the late nineteenth century French symbolists. Here we should note that some of Souza’s nudes are sexually aggressive as well as sensuous at the same time, though obviously not threatening. But Souza’s threatening female is bestial, carnivorous and vividly grotesque. It can be observed that Souza turns the represented figure itself into a fetish object (or primitive deity) so that it becomes re-assuring rather than dangerous, circumventing her threat. Psychoanalysis also draws attention to the unconscious imagery of woman with prominent row of teeth as representing the penis devouring female genitals. Interestingly, Souza has painted several such faces, sometimes titled Laughing Head or Queen, which would signify ‘castration’ syndrome. However, we should note that the initiator of Freudian Psycho-analytical research in India, Girindra Sekhar Bose, had in 1920s pointed out that the castration dread in Indian society was less in intensity. Therefore the possibility of deification or iconization of the female.

Souza’s drawings and paintings of couples in love-making postures give rise to the question if he wished to imply sexual activity as torture as well as animality. More than Souza’s single nudes, it is the couples which some critics have classified as representing ‘sin’ when they are juxtaposed against the delineations of biblical subjects. The eminent theater director and critic Ebrahim Alkazi terms them as ‘seasons in hell’, thus in a way also giving them a Biblical context. In the love-making couple of 1964, in their crawling postures as well as in the woman’s transformed arms resembling animal like fore-legs, the bestial suggestion is unmistakable. Alkazi’s phrases are appropriate, instead of a ‘game of passion’ between lovers, the ‘sense of claustrophobia and suffocation suggests an underworld of coarseness and malevolence.’ Similar sense of claustrophobia prevails in the painting of 1962 in which a woman is forcibly held lying on her belly, while Souza is compelling the on-looker to gaze at the act of penetration by a monstrous male, the whole composition resembling a scene of torture.

The unusual aspect of such paintings is quite a contrast with the lyrically drawn love-making couple dated 1959. Souza’s innovative genius is reflected in the manner he represented naked man and woman seated on a chair and united in love-making (painted in 1966). Prominence is given to the merging of their bodies and limbs within each other as well as the female sexual parts, which are displayed towards the on-looker and constructed in broad brushwork. Significantly in one of his late statements Souza thought of claiming that he created modern erotic art with its roots in medieval temple sculpture of Khajuraho and Konarak, and made it flower into an entirely contemporary expression.

Christian Themes

Souza’s involvement with Christian subject matter began during his years as an art student in Mumbai. As a Goa-born Christian drawing from biblical themes was as natural to him as the interest in Hindu subject matter by the Hindu artist. In the case of the Hindu artist it would be furthermore an act of nationalism as well as an assertion of identity during the colonial rule. In the case of Souza it will be his manner of announcing himself as a Goan Christian, that is both at national as well as regional level. It is my contention that gradually the depiction of Christian themes became a serious concern for Souza as he continued to mature as an artist. In Goa as a youngster he had witnessed the pomp of the church rituals and the routine Christian iconography of what was rather a second-hand Portuguese version of European art. But during the London and Paris years he was directly exposed and confronting the awe-inspiring masterpieces of Christian subject-matter as well as the special caliber of each individual European master painter which was more a challenge of widening the repertoire of his themes.

Souza used the term ‘religion’ for his Christian themes as we may note in the following quotation: ‘For me the all pervading and crucial themes of the predicament of man are those of religion and sex…in Hindu religious-erotic philosophy these themes are coincidental and mutually illuminating. They are not in conflict. But within the Christian faith they are, of necessity in discord..’

It is evident that Souza felt the need to explain the co-existence of imageries like nudes and crucifixion in his paintings, and perhaps it is here that he found it relevant to note that as an ‘Indian’ it is possible for the same ‘mind’ to reconcile the two antinomous themes. Yet the rhetoric coined by some critics about Souza’s concern with ‘sin’ and ‘spirituality’ needs to be questioned because neither has sexuality been considered as ‘sin’ by him nor do Christian themes necessarily represent ‘spirituality’. We have to locate a personal reason for Souza to depict episodes from Christ’s sacrifice. Christ for Souza becomes a personal symbol as well as a symbol of how men committed cruelty on other men.

Therefore in my opinion Christian subject-matter opened a window for Souza to relate to European art more than any other Indian painter. This is where his being a Goan Christian (Roman Catholic for that matter) was an advantage, that is to say standing in front of Biblical paintings would be like ‘home-coming’, especially in the most appropriate setting of the great church interiors of Europe. Therefore Souza’s Christian paintings reveal a facet of his creativity which is not only unique for an Indian modern painter, but this is how Souza could share with the ethos of a European painter and emerge eventually, I would like to call, a ‘universal’ painter. Neither could have an Indian painter concretized Christ’s passion scenes with such spontaneous dexterity as has been done by Souza (knowing all the ins and outs so to speak of the icons and their meanings). Some observers of Souza have floated the view that he has to be understood essentially as a Goan. Souza’s Christ departs radically from Western iconography; he is denied dignity and divinity in order to illuminate the artist’s own tortured obsessions with the mystery of life and faith’. Virgin Mary has kinship with the mother as Goddess, beloved of Indian tradition. Souza’s Madonna and Child of 1962 does not have the remote majesty but is infused with approachable humanity.

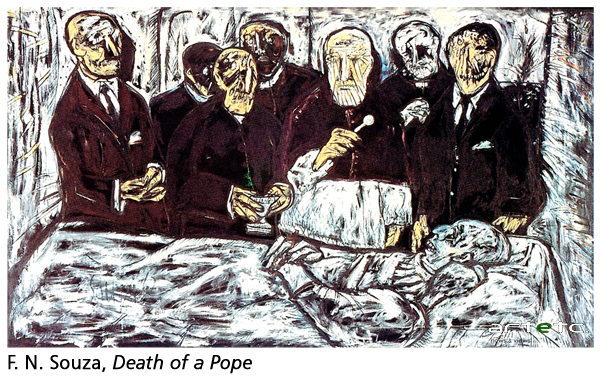

We may begin with the analyses of Lament for the Dead (1951) and The Death of the Pope (1962), both of these should be considered together, which are based on Souza’s direct experience of European art. The Death of the Pope needs in-depth analysis which is a critical as well as revolutionary work especially in terms of handling a Christian subject-matter. It is apparent that it was Souza’s answer to much talked about variations that Francis Bacon had done over Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, during the early 1950s.

We may begin with the analyses of Lament for the Dead (1951) and The Death of the Pope (1962), both of these should be considered together, which are based on Souza’s direct experience of European art. The Death of the Pope needs in-depth analysis which is a critical as well as revolutionary work especially in terms of handling a Christian subject-matter. It is apparent that it was Souza’s answer to much talked about variations that Francis Bacon had done over Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, during the early 1950s.

Though Lament for the Dead (1951) relates to ‘the Death of the Pope’ (1962) thematically, but the iconography of the earlier painting with the bending grieving female figure also suggests that it represents the death of Souza’s own father, and the lamenting woman as his mother. This painting unconsciously combines Christian iconography with an event in personal life which Souza had not seen directly but had been ingrained in his subconscious. The male figure in yellow holding the dead man’s head could be the priest, while other two women (probably family members) are sharing the grief.

For his ‘religious’ paintings Souza chose from the episodes of Christ’s suffering, known as ‘passion’ series, i.e., from the episode when he was captured, through trial and crucifixion followed by subsequent events. In 1941 Souza did one of his earliest drawings delineating Crucifixion which shows the set of three bodies nailed on to the crosses, silhouetted against the sky, the two of them flanking the central one were actually ordinary thieves. I am reminded of the important etching of the same theme by Rembrandt which Souza may have seen in a book. Compositions with single cross or the set of triple crosses, Souza continued to draw or paint even during his old age. In fact often any playful scribbling by him would result into a Crucifix. Most forceful Crucifix was painted in 1960, which is perhaps the one acquired by Tate Gallery.

The imposing centralized nailed body is the personification of suffering grieved by two disciples, one of whom gestures towards Christ’s body, the other tries to cover his face. It is this one which has been compared with both Grunewald and Graham Sutherland. But before this Souza had done a very dramatic scourging episode called Christ Tormented (1958) contrasting the victim’s suffering with the delight of the demonic tormentors. It is here that the much talked about ‘Expressionism’ of Souza is conspicuous that we could juxtapose this painting with some of the episodes of Christ’s Life painted by Emile Nolde, the German Expressionist painter.

Souza’s Christ in the Garden of 1957 is to be understood as his version of the iconography of ‘Christ’s Agony in the Garden’. It is that moment when Christ received the visionary inspiration to give up himself to the Roman authorities and is thus the first episode in ‘Passion’ cycle culminating with Crucifixion. It is remarkable to observe how Souza has combined his own way of visualizing the face as well as his landscape ‘genre’ to give it a biblical connotation. It is an impressive ‘mask’ of fear, sadness and fatalistic inevitability, which is ‘looking through’ the future horrible events to occur.

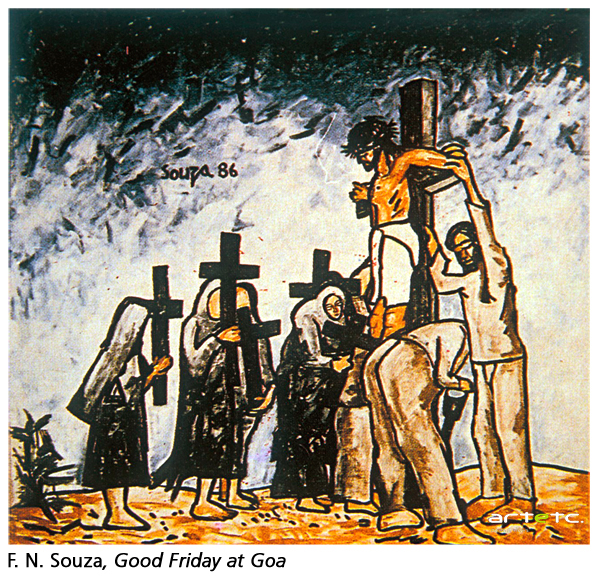

A particular Biblical painting which is sometimes connected with Souza’s Goan Christian experience is the one titled Good Friday at Goa. Iconographically it depict Three Marys at the Crucifixion, each of them holding up a cross, Mary the mother of Christ, Mary the mother of St. James and Mary Magdalene. It is painted with thick patches of black and blue for the sky and chrome yellow for Christ’s body and the foreground indicating the tropical sun and thus an effect of tragic atmosphere has been built up.

A particular Biblical painting which is sometimes connected with Souza’s Goan Christian experience is the one titled Good Friday at Goa. Iconographically it depict Three Marys at the Crucifixion, each of them holding up a cross, Mary the mother of Christ, Mary the mother of St. James and Mary Magdalene. It is painted with thick patches of black and blue for the sky and chrome yellow for Christ’s body and the foreground indicating the tropical sun and thus an effect of tragic atmosphere has been built up.

‘Christ at Emmaus’ is again a miraculous appearance of Christ, that Souza painted two times in 1958 and in 1995 in slightly distinct styles of London phase and New York phase. Two disciples were chosen to witness the miracle of revealing himself to them when Christ broke bread and offered it to them as their unacquainted companion at the meal in an inn. Souza chose the responses of the two personages towards the central figure to suggest in a summary manner the discovery of the diving presence. That Souza should have also grappled with the ‘Last supper’ need not come as a surprise. He definitely wished to propose an original arrangement for this symbolical meal, as in the drawing of 1959, in which the disciples are seated on two sides of an ‘L’ shaped table and Christ is placed off centre. Among the more than half a dozen later versions the one dated 1989 is colorful against a dark backdrop, with frontal grouping of the disciples. But placement in clusters of six heads on either side of Christ makes this painting appear much different than the more familiar type of Leonardo da Vinci. The haloed Christ is holding up a monstrance, that is a vessel bearing a relic. A critic has characterized the faces of disciples by the term ‘mutants’, while discussing such paintings. Souza’s several versions of Mystic Repast, (1953), Frugal Meal (1959) should also be mentioned here, which suggest poverty as well as symbolize Christ’s ‘Last Supper’, when he distributed pieces of bread to his disciples forewarning his sacrifice. It is significant that Picasso also had painted a young couple, entitled Frugal Meal (1904) to serve as prototypes for Souza.

Souza in America

Souza’s years in America should be regarded as a significant aspect and phase of his life as an artist. He left for U.S.A., in 1967 at the height of his fame in London and spent more than three decades there in what may be considered relative obscurity. No Indian or Western critic has explored this long phase of Souza’s artistic output, during the heydays of American Abstract-Expressionism and Pop Art (I have attempted this in the longer version of this essay). During the initial years in America he seemed to have been enthusiastic partly due to having married a young girl (now for the third time) from whom a son was born in 1971. Souza reported about the birth in a letter to Husain and about his new joyful attitude to the critic S.V. Vasudev in Mumbai.

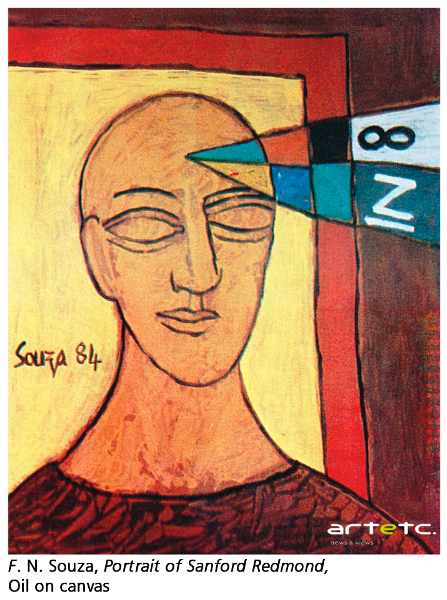

The positive aspect of American years has been the influence of the American scientist and thinker Sanford Redmond. The impact of the American scientist on his thinking is clear as Souza acknowledged so himself at the East and West Encounter, Mumbai, which is documented by Marg Publicantions in 1987. Souza had based his scientific philosophy on Sanford Redmond’s thesis of ‘Nature in an Altered Perspective’. The critic Jag Mohan explained that Souza had reconciled this latest scientific theory of the universe with the ancient, almost forgotten Sankhya philosophy of sage Kapila. Souza wrote the book ‘White Flag Revolution’ (1982) to provide the balm and balsam for the troubled world threatened by nuclear disaster. Anthony Ludwig, the American admirer of both the scientist as well as the artist, contributed an essay for the 1986 exhibition held at Delhi’s Dhoomimal Gallery. He claimed that humanity’s dreadful march into oblivion has always agitated Souza’s conscience. Christ betrayed and Crucified, becomes the symbol for the forthcoming ugliest sin of humanity – the thermo nuclear war – more barbarous than nailing Christ on cross. Ludwig thus gives a new meaning to Souza’s Christian themes. Discussing Souza’s recent Last supper, Ludwig explains that each of the 12 disciples is a ‘mutant’. Significantly in his Portrait of Sanford Redmond (1984), Souza recorded the scientist whose philosophy and thinking had impressed him serving as a kind of raison d’etre for his long sojourn in New York. In his imagery, Souza has incorporated Tantric notion of ajna chakra plexus on the forehead of the scientist/ thinker from which emanate the rays of his theory. With clean shaven head and meditative face (the eyes are shut) of the scientist, Souza has added another analogy, that of the opening up of Shiva’s third eye. The signs ‘IN8’ written on the emerging rays comprising of several colors, may refer to some scientific symbolism.

The positive aspect of American years has been the influence of the American scientist and thinker Sanford Redmond. The impact of the American scientist on his thinking is clear as Souza acknowledged so himself at the East and West Encounter, Mumbai, which is documented by Marg Publicantions in 1987. Souza had based his scientific philosophy on Sanford Redmond’s thesis of ‘Nature in an Altered Perspective’. The critic Jag Mohan explained that Souza had reconciled this latest scientific theory of the universe with the ancient, almost forgotten Sankhya philosophy of sage Kapila. Souza wrote the book ‘White Flag Revolution’ (1982) to provide the balm and balsam for the troubled world threatened by nuclear disaster. Anthony Ludwig, the American admirer of both the scientist as well as the artist, contributed an essay for the 1986 exhibition held at Delhi’s Dhoomimal Gallery. He claimed that humanity’s dreadful march into oblivion has always agitated Souza’s conscience. Christ betrayed and Crucified, becomes the symbol for the forthcoming ugliest sin of humanity – the thermo nuclear war – more barbarous than nailing Christ on cross. Ludwig thus gives a new meaning to Souza’s Christian themes. Discussing Souza’s recent Last supper, Ludwig explains that each of the 12 disciples is a ‘mutant’. Significantly in his Portrait of Sanford Redmond (1984), Souza recorded the scientist whose philosophy and thinking had impressed him serving as a kind of raison d’etre for his long sojourn in New York. In his imagery, Souza has incorporated Tantric notion of ajna chakra plexus on the forehead of the scientist/ thinker from which emanate the rays of his theory. With clean shaven head and meditative face (the eyes are shut) of the scientist, Souza has added another analogy, that of the opening up of Shiva’s third eye. The signs ‘IN8’ written on the emerging rays comprising of several colors, may refer to some scientific symbolism.

The half-size nude figure with large breasts and generative organ has been titled Prakriti Yoni, (1984). It is for the first time Souza used Indian titles. Of course we are reminded of the terra-cotta prototypes of the female icons from early Indian sculpture, which for Souza now represents Redmond’s Theory of Nature. The ‘Y2k Nude’ (1999) is posed as if seated or half reclining on bed, possessed with enormous breasts while the device of small head imparts it a huge scale. These female figures with large breast could be understood with the psycho-analytical interpretation of the breast. The breast is the object of oral wishes, impulses and anxieties and is synonymous, with ‘the mother regarded as a part-object’, or ‘the mother regarded as a need-satisfying object’. The concept refers not only to the breast as a sucking organ but also to the infant’s obliviousness of the mother’s person.

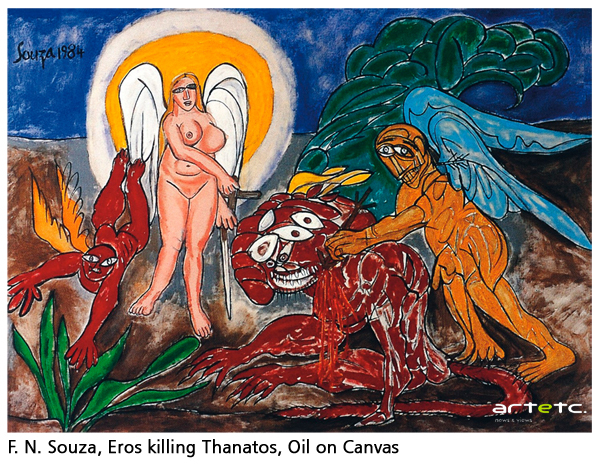

Eros Killing Thanatos (1984) now in the NGMA, New Delhi, is not only a major painting from Souza’s American period, but also reflects his new zest for life perhaps under the influence of Redmond’s philosophy and personal interest in Freud. I quote here the psychoanalytical explanations of the two concepts which so appropriately explains Souza’s imagery: Eros is the Greek God of Sexual Love used by Freud to personify the life and the sexual instincts. Eros is contrasted with ‘Thanatos’, the god of Death, that is the personification of the ‘Death Instinct’. Freud adopted Eros as poetic metaphor rather than a scientific term. The metaphor derives from (a) the fact that Eros was the secret lover of psyche and (b) the fact that his role was to co-ordinate the elements which constitute the universe. ‘It is he who brings harmony to chaos….’ In Souza’s painting a voluptuous female figure is collaborating with Eros who could be psyche, but she too has been given wrings. Souza’s imagery of Thanatos is the kind of demonic creature invented by him over the years which is the copulating savage like crossbreed creature in the painting ‘Fall-out Mutation’, undated, which is also the creature pursuing a female (The Red Curse) dated 1962. The mutating creature from the hell, the Devil, is described by Freud as the Lord of Hell and the Adversary of God as super male with horns, tail and a big penis-snake. Souza’s imageries uncannily match with these descriptions.

Eros Killing Thanatos (1984) now in the NGMA, New Delhi, is not only a major painting from Souza’s American period, but also reflects his new zest for life perhaps under the influence of Redmond’s philosophy and personal interest in Freud. I quote here the psychoanalytical explanations of the two concepts which so appropriately explains Souza’s imagery: Eros is the Greek God of Sexual Love used by Freud to personify the life and the sexual instincts. Eros is contrasted with ‘Thanatos’, the god of Death, that is the personification of the ‘Death Instinct’. Freud adopted Eros as poetic metaphor rather than a scientific term. The metaphor derives from (a) the fact that Eros was the secret lover of psyche and (b) the fact that his role was to co-ordinate the elements which constitute the universe. ‘It is he who brings harmony to chaos….’ In Souza’s painting a voluptuous female figure is collaborating with Eros who could be psyche, but she too has been given wrings. Souza’s imagery of Thanatos is the kind of demonic creature invented by him over the years which is the copulating savage like crossbreed creature in the painting ‘Fall-out Mutation’, undated, which is also the creature pursuing a female (The Red Curse) dated 1962. The mutating creature from the hell, the Devil, is described by Freud as the Lord of Hell and the Adversary of God as super male with horns, tail and a big penis-snake. Souza’s imageries uncannily match with these descriptions.

The very last works of Souza (during the late 1990) were done with a fluid liquid leaving a kind of dark brown line and could be used on any kind of paper. These have been named as ‘chemical paintings’ and drawn very quickly and spontaneously, an asset that Souza always possessed. The point is that any scribbling by Souza will hold the viewer’s interest. This brings up the topic of Souza’s drawings which are very close to his style of painting because the finished work is based on structure which is constructed with lines. This leads to my view that Souza’s style as well as whole career could be discussed using mostly his drawings. Apropos the developments in Souza’s line, I would like to observe that never was so much activity done and accomplished pictorially solely with the use of line and linear brush strokes as has been done by Souza. I enumerate: thin, wirey, incisive, sharp, lyrical, crystalline, staccato, attenuated, angular, jerky, thick, board, short, long, fluid, sweeping, energetic, powerful, drawn with the nib of a pen, thin sable-hair brush, wide flat brush, soft graphite, thin line with centipede like off-shoots on both sides, sketchy, finished, vicious, modulated and so forth.

The very last works of Souza (during the late 1990) were done with a fluid liquid leaving a kind of dark brown line and could be used on any kind of paper. These have been named as ‘chemical paintings’ and drawn very quickly and spontaneously, an asset that Souza always possessed. The point is that any scribbling by Souza will hold the viewer’s interest. This brings up the topic of Souza’s drawings which are very close to his style of painting because the finished work is based on structure which is constructed with lines. This leads to my view that Souza’s style as well as whole career could be discussed using mostly his drawings. Apropos the developments in Souza’s line, I would like to observe that never was so much activity done and accomplished pictorially solely with the use of line and linear brush strokes as has been done by Souza. I enumerate: thin, wirey, incisive, sharp, lyrical, crystalline, staccato, attenuated, angular, jerky, thick, board, short, long, fluid, sweeping, energetic, powerful, drawn with the nib of a pen, thin sable-hair brush, wide flat brush, soft graphite, thin line with centipede like off-shoots on both sides, sketchy, finished, vicious, modulated and so forth.

Factually speaking, Souza’s paintings (oeuvre) need to be considered in the context of Pan-Indian Modernism during the mid-twentieth century, i.e. at national level emerging at regional level in western India, but maturing, growing and fructifying at International level, especially because he lived in London and New York for most of the half century (1949-2002). Souza is a worthy successor to some of the best European artists of the first half of 20th century. As a creative personality, Souza has the place as a Universal painter on the analogy of several noble-prize winning novelists and poets belonging to different countries of the world.

His early serious critic Edwin Mullins (1962) had discussed Souza’s nude paintings in the context of European art such as Matisse, Picasso and Rouault. It was not only in terms of their influences but also to give Souza, a non-European artist, a place in the mainstream of Western art. Even if Mullins had referred to Souza’s own Indian heritage for the theme of the female nude, the English critic did not use this notion to justify this forte of Souza. I would like here to insist that it was Souza’s temerity which made him to perceive himself as the successor of the above masters. Souza has as much command on the female form as well as the plasticity of the line to delineate with equal ease as does Matisse and as does Picasso. Souza’s nudes match with the sensuality of the former and the eroticism of the latter as well as he had absorbed the stark sensuality flaunted by Rouault’s nudes particularly titled Prostitute, who walk about lifting their chemises. Undoubtedly Souza had developed tremendous formal inventiveness of pictorial language due to his closeness as well as distance with the ‘female object’. This may have been among the reasons for the acceptance and recognition that Souza had received in London’s art world of the 1950s.