- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Love of Life (that) Spills Over

- A Continuing Multiplication

- From Painting to Print

- Intimate Involvement

- Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

- (Hi)Story of the Garhi Printmaking Studios, New Delhi

- Surinder Chadda

- Ramendranath Chakravorty

- Group 8

- Mother and Child: A Screenplay

- Straddling Worlds

- A Brief History of Printmaking at Santiniketan

- Vignettes from History

- Southern Strategies

- The Forgotten Pioneer: Rasiklal Parikh

- Printmaking in the City Of Joy

- Amitabha Banerjee: His Art and Aesthetic Journey

- Local Style and Homogenizing trends: Early Medieval Sculpture in Galaganatha

- English China: Delicate Pallid Beauty

- The Beauty of 'Bilal'

- Photo Essay

- The Way of The Masters: The Great Artists of India 1100 –1900

- Striving Towards Objectivity

- The Art of Sculpting In the Contemporary Times

- An Artistic Framework for an Alternative to Ecology

- Bidriware and Damascene Work in Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art

- A Lowdown on the Print Market

- The 'bubble' and the 'wobble'

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata: June – July 2011

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

- Christie's Jewellery Auction at London, South Kensington

ART news & views

From Painting to Print

Volume: 3 Issue No: 19 Month: 8 Year: 2011

Features

Historical roots of printmaking in India.

by Nanak Ganguly

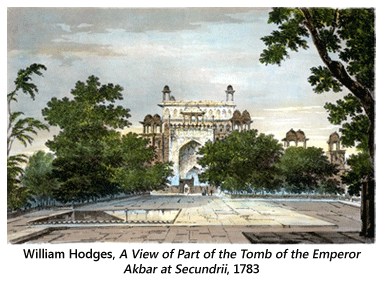

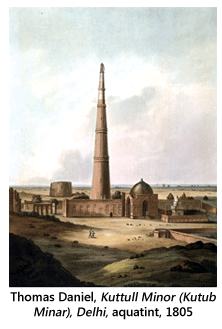

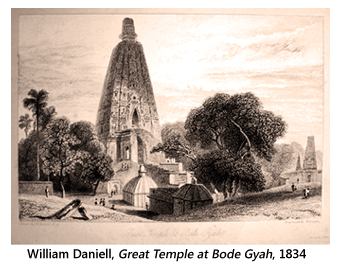

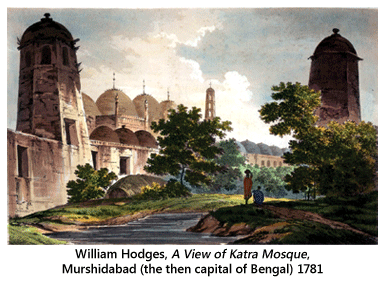

One of the most notable artists to have captured the Indian panorama in his paintings was William Hodges (1744-97) who traveled to India between 1780-83, producing his Select Views of India in 1787. Hodges received permission from the East India Company to travel to India as an artist in 1778. For accuracy of observation and attention to atmospheric conditions, Hodges had an exceptional training. He also had an introduction to Warren Hastings. He was the first professional landscape painter to visit the sub-continent. The other notable artists were the uncle and nephew team of Thomas (1749-1840) and William Daniell (1769-1837) who toured the country extensively, making sketches and watercolors which they took back to England where they produced the famous six volume series of aquatints, Oriental Scenery. Unlike Hodges, who was funded by the Company and subsequently by Hastings out of his own pocket, the Daniells combined their artistic talent with dogged endurance, determination and character;

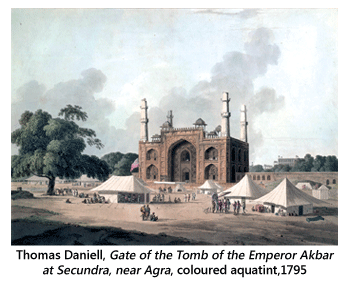

One of the most notable artists to have captured the Indian panorama in his paintings was William Hodges (1744-97) who traveled to India between 1780-83, producing his Select Views of India in 1787. Hodges received permission from the East India Company to travel to India as an artist in 1778. For accuracy of observation and attention to atmospheric conditions, Hodges had an exceptional training. He also had an introduction to Warren Hastings. He was the first professional landscape painter to visit the sub-continent. The other notable artists were the uncle and nephew team of Thomas (1749-1840) and William Daniell (1769-1837) who toured the country extensively, making sketches and watercolors which they took back to England where they produced the famous six volume series of aquatints, Oriental Scenery. Unlike Hodges, who was funded by the Company and subsequently by Hastings out of his own pocket, the Daniells combined their artistic talent with dogged endurance, determination and character;  and traveled the innermost parts of a virtually unknown eighteenth century "Hindoostan" (as the firangis lovingly referred to it) from 1786-1793. They observed with a painter's eye Mughal and Dravidian antiquities and the rural life around them. William kept a diary, and this, combined with annotated pencil drawings, watercolors and oil paintings, gives us a picture of their abundant talent.

and traveled the innermost parts of a virtually unknown eighteenth century "Hindoostan" (as the firangis lovingly referred to it) from 1786-1793. They observed with a painter's eye Mughal and Dravidian antiquities and the rural life around them. William kept a diary, and this, combined with annotated pencil drawings, watercolors and oil paintings, gives us a picture of their abundant talent.

The extent to which Thomas Daniell was indebted to Hodges is debatable. Certainly, the Daniells were at pains to denigrate his influence, his art and his accuracy. Like the Daniells, Hodges continued to work from his Indian sketches after his return to England. But in a sense, the Daniells used the best technology of their time to obtain exact perspective control: the camera obscura and an innovative reproduction method for serial printing of aquatints so obtained. They embellished this process with an imaginative use of artistic license in the final composition in order to convey a greater sense of the overall site than a narrower perspective could accurately portray.

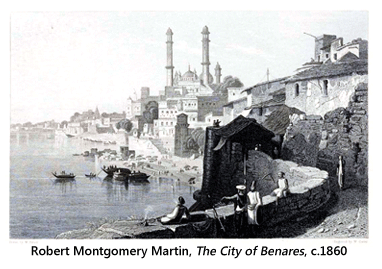

It was the idea of commercially exploiting their artistic work in India that caused the Daniells to conceive the idea of producing multiple sets of prints. This endeavour was obviously to emulate the example of Hodges, whose Select Views were also issued in two successive batches of 24 aquatints each. Daniells set about learning the craft of aquatinting, far surpassed their predecessors output, moving beyond the 48 prints issued by Hodges to a total of six-volumes of 24 prints each, supplemented by two views of the Taj. Oriental Scenery is the title usually given to this monumental six-volume work of 144 hand-coloured aquatint engravings. These publications introduced many of India's most famous buildings and sites to the European public: the temples at Thanjavur and Gaya, the forts at Rohthasgarh and Allahabad, the Taj Mahal and the British residences at Madras and Calcutta. Scenic wonders such as waterfalls, forested hills or the distant snows of the Himalayas offering the most resonant examples of the British vision of sublime and picturesque India. The better we know this work the more we can take in trust a vision of a sub-continent, which in actuality we can never see. But having seen it, the Indian landscape with its moving figures takes on a

whose Select Views were also issued in two successive batches of 24 aquatints each. Daniells set about learning the craft of aquatinting, far surpassed their predecessors output, moving beyond the 48 prints issued by Hodges to a total of six-volumes of 24 prints each, supplemented by two views of the Taj. Oriental Scenery is the title usually given to this monumental six-volume work of 144 hand-coloured aquatint engravings. These publications introduced many of India's most famous buildings and sites to the European public: the temples at Thanjavur and Gaya, the forts at Rohthasgarh and Allahabad, the Taj Mahal and the British residences at Madras and Calcutta. Scenic wonders such as waterfalls, forested hills or the distant snows of the Himalayas offering the most resonant examples of the British vision of sublime and picturesque India. The better we know this work the more we can take in trust a vision of a sub-continent, which in actuality we can never see. But having seen it, the Indian landscape with its moving figures takes on a new dimension which transcends modernity.

new dimension which transcends modernity.

European Calcutta was confined throughout the 18th century, to a space of little over a square mile with the fort at the western end and skirting the Hooghly and Lal Dighi in the heart of it. Although there are written descriptions of the first fifty years 1690-1740, there are hardly any pictures of it, and of the unplanned growth of the native or the "Black Town" of that period. Of the two or three black and white engravings executed before 1750 which exist, the most important is the only extant engraving of the long demolished Old Fort William, by a Dutch artist, G. Vandergucht, published in 1736. Johannes Zoffany, possibly the best-known professional painter to have ever visited India, came in 1783. He had drawn portraits of the Governor General Warren Hastings and his wife and painted the Last Supper, a mural for the newly constructed St. John's Church. However, he too chose to ignore Calcutta scenes, and it was not until William Hodges arrived around the early Eighties, that we got what was probably the first landscape of Calcutta- a view of the harbour as seen from the present Fort William.

The period that followed belonged to the Daniells. Thomas Daniell (1770-1840) and his nephew William (1770-18370), wrongly quoted by some scholars as the "Daniell Brothers", were inseparable from each other in their work. Both became memorable for their mighty opus: a six part double elephant folio containing 144 plates including twelve celebrated views of European Calcutta, symbolizing in the public mind the entire corpus of British and European Art in India. In 1786, Daniells set themselves to depict their Twelve Views of Calcutta employing the newly invented process of aquatint, apart from three portrayals of the Black Town,  two of Chitpore Road, Calcutta's oldest street, and the temple of Govind Ram Mitter, also on Chitpore. Capt. William Baillie Fraser, who followed the Daniells, too concentrated on white Calcutta. The only extant picture of Military Orphan's School, Howrah, is the only picture of that suburb during those times.

two of Chitpore Road, Calcutta's oldest street, and the temple of Govind Ram Mitter, also on Chitpore. Capt. William Baillie Fraser, who followed the Daniells, too concentrated on white Calcutta. The only extant picture of Military Orphan's School, Howrah, is the only picture of that suburb during those times.

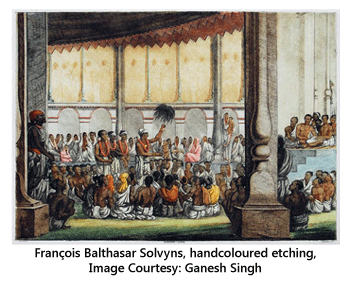

Within less than a century of Job Charnock's famous noon day halt on that fateful rainy afternoon of 24th August ,1690, Calcutta had grown both in beauty and importance. Travelers called Hastings's Calcutta a miniature tropical London. It was already the political, commercial and intellectual hub of India. While all the attention was being lavished on white Calcutta, the Black Town, seething with life and exotic variety, remained uncaptured on the palette. 7Madame Belnos, a French artist and Sir Charles D'oyly, minimized this shortfall by to a small extent. But it was Balthazar Solvyns (1760-1824), a Franco-Belgian who arrived in Calcutta in 1791 and placed it on the artistic map. A Flemish marine artist, born to a prominent merchant family in Antwerp, Calcutta was his home for thirteen years. When he arrived in Calcutta, the debate over sati was just beginning as missionaries, among others, condemned official toleration of the "dreadful practice" and called for its suppression. Of all the Hindu customs, none more fascinated or appalled the Europeans than “suttee”, the practice of widow burning (within the city of Calcutta, under jurisdiction of British law, suttee had been prohibited since 1798, but outside Calcutta, the “dreadful practice” flourished in Bengal in epidemic proportions). Tilly Kettle (1735-1786) painted the serene young widow bidding farewell to her relatives, Johann Zoffany (1733-1810), in one of the three paintings he devoted to the subject, but in the early 1780's William Hodges witnessed a suttee near Benaras and made a drawing at the scene. He subsequently completed a painting, ”Procession of a Hindu Woman to the Funeral Pyre of her Husband” that served as the basis for the engraving accompanying his description in Travels in India.  Solvyns in his portrayal of suttee, seeks to record faithfully and accurately as an observer what he witnessed in order to give fullness, truth and spirit to the resemblance. However, he no less than his contemporaries, brings a mixture of admiration, sympathy and condemnation. Unlike Tilly Kettle, Thomas Hickey, and Johan Zoffany who enjoyed the patronage of the nabobs and nawabs alike, Solvyns initially was more of a journeyman artist. Initially, he provided decoration for celebration and balls, cleaned and restored paintings, and offered instruction in oils, watercolours, and chalk. In 1794, inspired by Sir William Jones, Solvyns announced his plan to publish A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos.

Solvyns in his portrayal of suttee, seeks to record faithfully and accurately as an observer what he witnessed in order to give fullness, truth and spirit to the resemblance. However, he no less than his contemporaries, brings a mixture of admiration, sympathy and condemnation. Unlike Tilly Kettle, Thomas Hickey, and Johan Zoffany who enjoyed the patronage of the nabobs and nawabs alike, Solvyns initially was more of a journeyman artist. Initially, he provided decoration for celebration and balls, cleaned and restored paintings, and offered instruction in oils, watercolours, and chalk. In 1794, inspired by Sir William Jones, Solvyns announced his plan to publish A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos.

Solvyns's works exhaustively captured the humble dwellings of the natives, the soaring temples and mosques, the teeming streets and bazaars, the gharries, rickshaws and palanquins, the bullock carts and the entire gamut of country craft dotting the Hooghly. With equal fastidiousness, Solvyns also recorded the festivities and ceremonies that accompany the Hindu way of life. But most charming of all was his portrayal of men and women from all echelons, including holy men in their distinctive garb, street characters in their individual costumes, musicians with their array of instruments and even eunuchs, without which the life of Black Town would have remained unknown. There was such demand for Solvyns pictures that John Gantz (British, 1772-1853) who had a lithographic press in Madras was induced to publish in 1827,  The Indian Microcosm, a set of twenty prints portraying some native trades and other bazaar characters. Gantz was a draughtsman for the East India Company, before working as an architect and lithographer based in Madras. Gantz and his sons Justinian Walter and Julius Walter completed many watercolour drawings of Madras houses, which were issued into prints. Without these artists, we would have no graphic record and visual record of Calcutta and the sub continent before 1850. Among the colonial powers of the world, none has been able to rival the British in the vastness and variety of the colonial and artistic legacy.

The Indian Microcosm, a set of twenty prints portraying some native trades and other bazaar characters. Gantz was a draughtsman for the East India Company, before working as an architect and lithographer based in Madras. Gantz and his sons Justinian Walter and Julius Walter completed many watercolour drawings of Madras houses, which were issued into prints. Without these artists, we would have no graphic record and visual record of Calcutta and the sub continent before 1850. Among the colonial powers of the world, none has been able to rival the British in the vastness and variety of the colonial and artistic legacy.

“In Patna around 1800's, the European community combined the same aloofness from Indian social life with similar interest in the picturesque, and it was this latter trait which gradually gave the Patna painters their expanded market. The city, which must have seemed at one time only a slightly more settled alternative to Murshidabad, was gradually seen to contain a new specialized demand. The Patna artists began to experiment with compositions of local Indian scenes…until about 1830 they had become perhaps the most lucrative branch of Patna paintings. The artists painted whole sets of 'Snapshots' known as 'Firkas' there were the familiar figures of the European compound: washermen, butlers returning from the market, tailors, maid servants. They portrayed the various bazaar tradesmen and craftsmen, peddlers, bangle sellers, butchers, fish-sellers, blacksmiths etc. They painted familiar town and village sights: elephants, ekkas, bullock carts, palanquins, pilgrims etc." (from Patna Painting, Mildred Archer, The Royal India Society. London, 1947)

A similar demand was being met by the lithographs of Sir Charles D'Oyly, which portray the same type of the subject. Archer writes,  "D'Oyly's career is of great interest, for while he was posted in Patna he set up the Bihar Lithography, where he employed a Patna artist, Jairam Das, as his assistant. Several of his books portraying Indian scenes and costume, which had a wide circulation amongst Europeans in India, were made at Bihar Lithographic Press, and it is interesting to speculate how far D'Oyly may have influenced the Patna painters in their style and subject matter, or alternatively, whether they in were making competent sepia drawings of the countryside and sketches for lithographs. Jairam Das received direct instructions from D'Oyly and was shown a wide range of work by Europeans." The results were electrifying. Captain Robert Smith in Pictorial journal of travels in Hindustan from 1828 to 1833 writes "for productions of the pencil, through, I was informed, the fostering care of Sir C D'Oyly, who has endeavoured, and with great success, to inspire the natives with some of his own pure taste and artist-like touches, instead of the hard dry manner of the Indian painters. I was much pleased with what I saw". Captain Smith of 44th regiment was himself a talented painter as well. In the Patna Museum there is a large scrapbook of his landscape, one of which shows himself seating under a huge umbrella sketching. While he was collector in Dacca from 1808-1812 he took lessons from George Chinnery the artist, who was living there also.

"D'Oyly's career is of great interest, for while he was posted in Patna he set up the Bihar Lithography, where he employed a Patna artist, Jairam Das, as his assistant. Several of his books portraying Indian scenes and costume, which had a wide circulation amongst Europeans in India, were made at Bihar Lithographic Press, and it is interesting to speculate how far D'Oyly may have influenced the Patna painters in their style and subject matter, or alternatively, whether they in were making competent sepia drawings of the countryside and sketches for lithographs. Jairam Das received direct instructions from D'Oyly and was shown a wide range of work by Europeans." The results were electrifying. Captain Robert Smith in Pictorial journal of travels in Hindustan from 1828 to 1833 writes "for productions of the pencil, through, I was informed, the fostering care of Sir C D'Oyly, who has endeavoured, and with great success, to inspire the natives with some of his own pure taste and artist-like touches, instead of the hard dry manner of the Indian painters. I was much pleased with what I saw". Captain Smith of 44th regiment was himself a talented painter as well. In the Patna Museum there is a large scrapbook of his landscape, one of which shows himself seating under a huge umbrella sketching. While he was collector in Dacca from 1808-1812 he took lessons from George Chinnery the artist, who was living there also.

D'Oyly became an opium agent in Patna in 1818 and started living in a large bungalow at Bankipore on the Ganges. D'Oyly published several of lithographs and engravings books in his lifetime – The Costumes and Customs of Modern India. The European in India was published in London in 1813,  followed by the Antiquities of Dacca in Dacca in 1816. In 1828 he published Tom Raw, where he refers to Chinnery and Griffin as 'the ablest limner in the land', and it is clear that his style was influenced by Chinnery. Bihar Amateur Lithographic Scrapbook was published in 1828. Mildred Archer mentioned about it, “in 1830 Views of Calcutta, sketches of the new road in journey from Calcutta to Gaya was published whereas Views of Calcutta and its Environs, lithographed and published by Dickinson & Co, London was published in 1848. This was presented to the Victoria Memorial Hall by Mrs. George Lyell in memory of her husband in 1932. It is not known whether D'Oyly had any direct contact with the better known Patna painters, though his assistant, Jairam Das, was related to many of them nor do we know whether D'Oyly actively influenced the Patna painters, but if a lithograph such as The Nautch (in the Bihar Lithographic Scrapbook) or some illustrations from Costumes of India are compared with the Patna paintings it is evident that one or the other has been influenced. It is possible that some of these lithographs were actually drawn on the stone by Jairam Das and his Patna assistants from D'Oyly's drawings. As late as 1880 Bahadur Lal II was making free copies of birds from D'Oyly and Christopher Webb-Smith's books, and in the Patna Museum there is a copy of the pictures Ord Bhawn or Hindu fakir from D'Oyly's costumes of India. D'Oyly may also have had a great influence on the Patna painters in their choice of subjects. His own subject matter - birds, costumes, scenes of Indian life such as gambling, music, and dancing parties, elephants, a dancing girl holding a dove - were identical to that of Patna pictures, and it is possible that at a time when the Patna painters were exploring the European market and trying to adapt their style to European fashions, D'Oyly and his press may well have been supplying them with a significant model” (-Mildred Archer, Patna Painting, The Royal India Society, 1947)

followed by the Antiquities of Dacca in Dacca in 1816. In 1828 he published Tom Raw, where he refers to Chinnery and Griffin as 'the ablest limner in the land', and it is clear that his style was influenced by Chinnery. Bihar Amateur Lithographic Scrapbook was published in 1828. Mildred Archer mentioned about it, “in 1830 Views of Calcutta, sketches of the new road in journey from Calcutta to Gaya was published whereas Views of Calcutta and its Environs, lithographed and published by Dickinson & Co, London was published in 1848. This was presented to the Victoria Memorial Hall by Mrs. George Lyell in memory of her husband in 1932. It is not known whether D'Oyly had any direct contact with the better known Patna painters, though his assistant, Jairam Das, was related to many of them nor do we know whether D'Oyly actively influenced the Patna painters, but if a lithograph such as The Nautch (in the Bihar Lithographic Scrapbook) or some illustrations from Costumes of India are compared with the Patna paintings it is evident that one or the other has been influenced. It is possible that some of these lithographs were actually drawn on the stone by Jairam Das and his Patna assistants from D'Oyly's drawings. As late as 1880 Bahadur Lal II was making free copies of birds from D'Oyly and Christopher Webb-Smith's books, and in the Patna Museum there is a copy of the pictures Ord Bhawn or Hindu fakir from D'Oyly's costumes of India. D'Oyly may also have had a great influence on the Patna painters in their choice of subjects. His own subject matter - birds, costumes, scenes of Indian life such as gambling, music, and dancing parties, elephants, a dancing girl holding a dove - were identical to that of Patna pictures, and it is possible that at a time when the Patna painters were exploring the European market and trying to adapt their style to European fashions, D'Oyly and his press may well have been supplying them with a significant model” (-Mildred Archer, Patna Painting, The Royal India Society, 1947)

The colonial rule impressed its presence in the sub-continent through the demarcation of a new world of 'high art' and the exclusive category of 'artists'. European painters and engravers who frequented India from the 1780's with a monopoly over the patronage of the emergent colonial elite, epitomized the new definition of the artist. Emulating the European example, a similar identity of an artist evolved in indigenous society by the mid-nineteenth century. While the western category of the "artist" was gradually loosening to accommodate Indians of middle class backgrounds who were privately trained in oil painting by European tutors, the category of 'artisan' included a mixed community of local painters, the draughtsmen and printmakers, who were responding equally to the pressures of westernization and new market demands. It is clear from these facts that the art activity of the Company men and amateur British painters did help in the setting up of an art school along the western lines. Towards the middle of 19th century, art schools in Madras(1853), Calcutta(1854), Bombay(1857), and Lahore(1878) were opened and the syllabi offered were derived from London's Kensington School.

epitomized the new definition of the artist. Emulating the European example, a similar identity of an artist evolved in indigenous society by the mid-nineteenth century. While the western category of the "artist" was gradually loosening to accommodate Indians of middle class backgrounds who were privately trained in oil painting by European tutors, the category of 'artisan' included a mixed community of local painters, the draughtsmen and printmakers, who were responding equally to the pressures of westernization and new market demands. It is clear from these facts that the art activity of the Company men and amateur British painters did help in the setting up of an art school along the western lines. Towards the middle of 19th century, art schools in Madras(1853), Calcutta(1854), Bombay(1857), and Lahore(1878) were opened and the syllabi offered were derived from London's Kensington School.

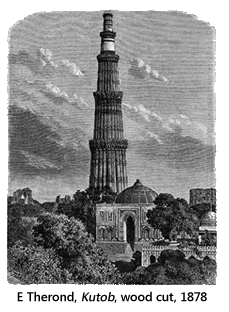

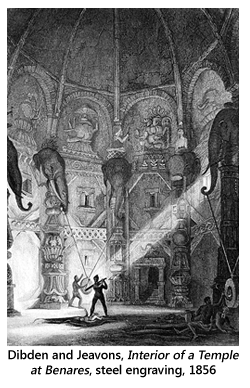

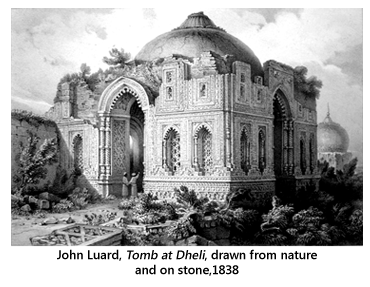

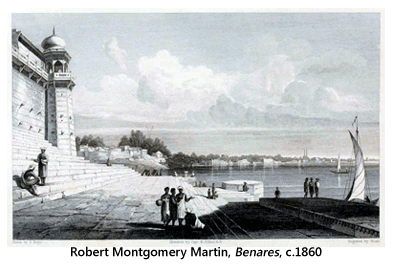

As the colonial power established its rule a number of foreign artists came to India with the hope of becoming rich overnight. These artists worked primarily in three techniques: oil on canvas, miniature painting in watercolour on ivory and watercolour on paper and prints made from them by engraving process. Notable engravers and printmakers were Hodges, Solvyns, Soltykoff, James Mofat, Colsworthy Grant, William Simpson, Robert Montgomery Martin, Dibden, Jeavons, E Therond, John Luard and the Daniells. The Great mutiny of 1857 had brought India a considerable attention in Britain and Day & Sons produced a large format book of tinted lithographs by Simpson. William Purser (1789-1852) was a painter and architect, his Aurangabad, from the ruins of Aurangzeb's Palace (from a sketch by Capt. Grindlay) watercolour on paper had been engraved by C F Hunt in Grindlay's Scenery, Costumes and Achitecture, chiefly on the Western side of India, 1830. Another European artist Eduard Hildebrandt (1818-1869), born in Gdansk, published Travel around the World, 'Reise um die Erde' lithographed and published in Berlin, which contained an attractive view of a mid century street scene in Bombay, 'Strasse in Bombay'.

which contained an attractive view of a mid century street scene in Bombay, 'Strasse in Bombay'.

Around the lanes and by-lanes that led to Calcutta's famed Kali Temple in Kalighat where migrant patuas settled, a unique school developed between 1830-1920 known as the 'Kalighat school'. Like some classic nineteenth century Bengali satires and a vast body of 'street literature' emanating from Battala in North Calcutta, the Kalighat patuas graphically represented the manner and life style of a decadent culture to serve the dual purpose of instruction and delight, where hypocrisy, particularly religious, received savage treatment with elliptical sweeps of heavy contour lines, embellished with coloured parallel shades, giving the feeling of bodily volume with water-soluble inks and colours, on stark surfaces sans background on cheap mill-made paper. Far more widespread, were the woodcut and metal engraved varieties of the Kalighat paintings, produced independently by the community of engravers at Battala. Probably the Kalighat painters themselves took their pictures to the wood engravers of Chitpur to have them replicated and more widely circulated in the market. Woodcut printing centered around indigenous Bengali printing and publishing at Battala. Initially, artisan and groups like ironsmiths, coppersmiths, gold and silversmiths (the kansaris, shankaris, swarnakars and karmakars) finding employment in the new British owned printing presses at Serampore and Calcutta, had adopted their old skills of working in metal towards preparing type-faces and engraved blocks. By the 1820s and 1830s, these printmakers became a separate community, working primarily with the wood-engraved block to suit the requirements of small sized pictures in the cheap illustrated Bengali lewd books of Battala. These books varied from religious narratives and almanacs to florid prose and adventurous stories. Since 1930s, the region around Battala emerged as the nucleus of Bengali printing and publishing with several small presses mushrooming all over Sovabazar, Darjitala, Ahiritola, Kumartuli, Garanhata, Simulia, Baghbazar - areas of north west Calcutta. These prints were flat, decorative, two-dimensional pictures, in marked tones of black and white.  The figures, like the figures in the rural pats were nicely stylized and non-naturalistic, with the emphasis on heavy black, curvilinear lines, and blunt hatchings to convey a sense of volume and density added with cross hatchings of little or ornamental motifs. In themes, as in style, the Battala prints replicated the Kalighat images, repeating the same stock of satire, mocking the dandyish babu, his corrupt life-styles and his subjugation by immoral women.

The figures, like the figures in the rural pats were nicely stylized and non-naturalistic, with the emphasis on heavy black, curvilinear lines, and blunt hatchings to convey a sense of volume and density added with cross hatchings of little or ornamental motifs. In themes, as in style, the Battala prints replicated the Kalighat images, repeating the same stock of satire, mocking the dandyish babu, his corrupt life-styles and his subjugation by immoral women.

During 1860s and 1870s, Kalighat patuas and the Battala engravers were locked in close competition, the latter freely incorporating the pats invading the market. But both the schools died with the onslaught of glossy, multicoloured and realistically drawn lithographs and oleographs and the popularization of photography. Also the popular art market of Calcutta was flooded around 1880 by hand-coloured lithographic pictures produced by the Calcutta Art Studio ran by the ex-students of the Calcutta School of Art and Crafts, and by the English chromolithographs, which made exact copies of the Art Studio pictures in a superior technique at just one-tenth of their price.

The arrival of Raja Ravi Varma's oleographs into the scene coincided with the construction of a new cultural elite the arbiters of middle class taste.