- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Love of Life (that) Spills Over

- A Continuing Multiplication

- From Painting to Print

- Intimate Involvement

- Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

- (Hi)Story of the Garhi Printmaking Studios, New Delhi

- Surinder Chadda

- Ramendranath Chakravorty

- Group 8

- Mother and Child: A Screenplay

- Straddling Worlds

- A Brief History of Printmaking at Santiniketan

- Vignettes from History

- Southern Strategies

- The Forgotten Pioneer: Rasiklal Parikh

- Printmaking in the City Of Joy

- Amitabha Banerjee: His Art and Aesthetic Journey

- Local Style and Homogenizing trends: Early Medieval Sculpture in Galaganatha

- English China: Delicate Pallid Beauty

- The Beauty of 'Bilal'

- Photo Essay

- The Way of The Masters: The Great Artists of India 1100 –1900

- Striving Towards Objectivity

- The Art of Sculpting In the Contemporary Times

- An Artistic Framework for an Alternative to Ecology

- Bidriware and Damascene Work in Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art

- A Lowdown on the Print Market

- The 'bubble' and the 'wobble'

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata: June – July 2011

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

- Christie's Jewellery Auction at London, South Kensington

ART news & views

Love of Life (that) Spills Over

Volume: 3 Issue No: 19 Month: 8 Year: 2011

Creative Impulse

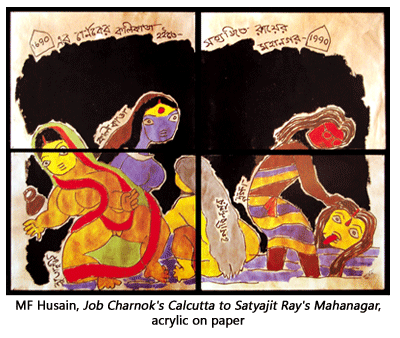

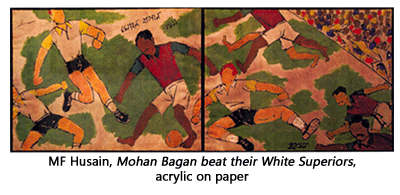

Manasij Majumder in Conversation with Husain

(The following article is based on an interview taken for an English daily in February 1993. Husain came to Calcutta in connection with the Wounds exhibition mounted by a Calcutta Gallery in response to the communal riots which broke out in Ayodhya and Mumbai after the Babri Mosque was razed on December 6, 1992. For reasons I cannot recollect now, the article was not published and I had forgotten all about it until recently when it was accidentally found lodged in a pile of old papers.)

“I was a boy, mother called me Maqbool and I have become (baney gaya hai) M F Husain.” This is how India's foremost contemporary painter sums up his life in his forthcoming autobiography1 he is now busy writing. The words, like a few pen-and-ink strokes in a brisk self-portrait, ideally describe one's impression about him in his presence when one meets him for an exclusive interview. This tall jean-clad, sage-like, barefoot and bearded artist bubbling with inexhaustible energy warms up instantly to talk on anything under the sun with a disarming simplicity that makes his interviewer feel free to ask him any question, though he cannot escape a subtle spell of his towering personality.

a disarming simplicity that makes his interviewer feel free to ask him any question, though he cannot escape a subtle spell of his towering personality.

Husain was recently in Calcutta - a city he frequently visits to exhibit in connection with the inaugural of Wounds exhibition mounted by the Centre for International Modern Art, in which he is represented by a large canvas shot through with a spirit of hope and harmony amidst all the gathering gloom in the country since the December 6 event last year. Since those days in the late thirties when he would paint huge film billboards, Husain has seldom been out of touch with people around him and he has rarely painted anything not out of his lived experience and not inspired by his response to life in India. Over a period of more than four decades this prolific painter has brought under his brush the vast panorama of reality that is India. People, places, myths, legends, epics in short the whole of India, past, present and timeless-have bustled into the picture spaces of the massive body of his works executed in a bewildering range of mediums and techniques.

An artist who has so much of “love of life [that] spills over” and who cannot paint abstract because of the very “sight of surging humanity all around”, the CIMA exhibition on Wounds was an exciting occasion for him to visit Calcutta. He is extremely worried about the sudden upshot of communalism but he is confident that it is a passing phase“a temporary setback for India's secular forces”. “For the Wounds exhibition, therefore, I have painted no scene of violence. I have done things like that before, as in the Assassination series but I believe communal harmony will reassert itself very soon.”

What's about art prompted by topical events? As an inveterate figurative painter who has always drawn upon such events to do thematic paintings, he believes that “on such occasion as now artists cannot afford to remain indifferent. He dismisses as “pure nonsense” the idea of pure art, that art should discard image or that canvas painting has no vogue in the West now as were claimed by the French artists participating in an Indo-French art camp, Confluence 2, in Calcutta recently. “Art is alienated from life in the West, they have lost touch with the finest elements of human existence. The West is now doing a lot of garbage.”

Husain has been mainly a canvas painter except for an occasion when he painted on the nude female torsos preserved in photographs. And he paints nearly always what the French artists called, image, that is figurative image and “my images do a lot of story-telling.” He doesn't mince his words, expressing his disgust about what is now being done in the West in the name of avant-garde art. “Their art is fraud or Freud,” Husain quipped cryptically.

“Indian art, too, has gone beyond the human figure. Our Nataraja is related to the Cosmoseven his nails are proportioned to the cosmic scale. The human figure in western art is related to human and physical realities only. But the West does not know the East.” regrets Husain. “We have no Andre Malraux to teach them about our art. But it is not always ignorance but bias against any tradition beyond theirs in the West.” He gives an example.

In 1969 Husain was in Germany showing a short film he did on the painted erotic sculptures in wood, from Nepal, of gods and men. “Around 1955 Picasso did about 300 erotic graphics drawings of copulating couplesnothing much besides that. They were shown all over the world even in India. So my audience in Germany thought that I had taken all this from Picasso. They know absolutely nothing of our heritage. Think of our Kamasutra the depth and variety of erotic pleasures! Even the great womaniser, Picasso, could never conceive anything like that.”

Husain wants contemporary Indian art to go abroad. Just as the world outside knows we are poised to make giant strides in our industry and technology, the time has come for Indian art to make global ventures.

Husain wants contemporary Indian art to go abroad. Just as the world outside knows we are poised to make giant strides in our industry and technology, the time has come for Indian art to make global ventures.

“If the West does not know Indian contemporary art it is because we have never projected it globally the right way.” The Government does nothing but cultural propaganda. India has to enter the global cultural arena. “But we cannot go on harping on our past art and past culture only we must break our sitar and invent a new instrument.” A great lover of Indian music, Husain puts it symbolically but “this can be done”, he adds, “only in visual arts, of all arts the only one absolutely free, and only if it is freed from interference by the pundits and the Governments.”

It is precisely in this context that he sees the launching of CIMA as an event of all India importance. “This new centre is going to play a foremost role”, Husain is more than sure, “to promote contemporary Indian art abroad, not just keeping sales in view, but exclusively on the strength of the merit. “This cannot be done by holding occasional shows in London and New York.” Husain had a solo show in New York in 1964 but not a single line about it appeared in the press.” Certainly that does not mean I am a lesser artist”, Husain indulges in no false modesty. He thinks CIMA is ideally equipped to take abroad properly curated shows of contemporary Indian art, backed by necessary resources and professionalism to make big impacts on the media, market and museums over there.

But there is something disturbing in the general response to our contemporary art in the West. They find it an offshoot of the modern western art of the first half of the twentieth century, Husain does not agree with this view, though he admits that “we have borrowed from the West when Indian art was on the threshold of the modern age. That was a historical necessity. We learnt Cubism which is the language of the century and we learnt from it to change the scale of reality and restructure it to the given space of the picture. With this we went to our own roots, to Tantric art, for example. And by the sixties Indian contemporary art came of age. We have discovered the element of mystery as the core of our culture.”

The West explores matter but the mystery of creation and existence is translated in Indian art. “That element is abundantly present in Bengal art today”, remarks Husain admiringly and cites the example of Ganesh Pyne but hastens to add “he is not the only example though.”

Another element that is typically Indian is our colour. There are a lot of colours in Rajasthan, most vivid, vibrant and sensuous. And colours in the South, particularly in Kerala, are “natural, but more refined abstract and intellectual.” These are two major sources of colours in Indian art today.”

Husain has always showered effusive praise on contemporary Bengal art. What is it that prompts him to do so? A figurative painter, and one who wants art to take its origin in the artist's interaction with reality, he feels at home in the art world of Bengal. Moreover, this is the city culturally most vibrant of all the cities in India. In no other city young people respond so passionately to art, music, theatre and poetry as they do here. “That may be one reason why art in Bengal does not look so flat as in the North.”

Husain often paints in public, drawing crowds to watch him in action and attracting a fresh publicity in the press. Last year he painted a series of canvases in Calcutta for a week and on the final day he undid the paintings by dabbing coats of white on them. It was high drama watched day after day by Calcutta's elite led by Mr Russy Modi and a piece of sensational news reported in the press stroke by stroke of the brush down to the last detail. Is it a publicity gimmick or his sheer love of showmanship?

“It is neither”, says Husain calmly, “I painted in public when I used to do cinema hoardings and I love sharing the thrill and excitement of painting with an audience present before me. I feel like a musician who creates his music in presence of his admiring audience.” And Husain paints with such speed and spontaneity that it seems painting does him as much as he does painting. “I don't need such props to boost my sales or my fame.” The paintings he did in Calcutta last year were not originally planned to be erased. But he felt hurt when on the fourth day a man told him that he was doing this to fetch high prices for his works. The next day he decided and announced that he would wipe the canvases clean after the paintings were done. Offers came to buy the painting at high prices and the money to go Mother Teresa. But he did not budge from his decision. “Ask any artist how it feels like undoing one's own creation, it is like killing your own child”, adds the artist with a soft sincere accent in his voice after a pause recalling all the pain of doing it.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- I do not know whether Husain later published, or has left a finished or unfinished manuscript of, his autobiography which he told me he was busy writing at the time.

- The art camp, Confluence, was organized jointly by Alliance Francaise, Calcutta, and Birla Academy in the first week of December, 1992 and participated by artists from both India and France. Indian participants were those who had received a spell of training at