- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Love of Life (that) Spills Over

- A Continuing Multiplication

- From Painting to Print

- Intimate Involvement

- Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

- (Hi)Story of the Garhi Printmaking Studios, New Delhi

- Surinder Chadda

- Ramendranath Chakravorty

- Group 8

- Mother and Child: A Screenplay

- Straddling Worlds

- A Brief History of Printmaking at Santiniketan

- Vignettes from History

- Southern Strategies

- The Forgotten Pioneer: Rasiklal Parikh

- Printmaking in the City Of Joy

- Amitabha Banerjee: His Art and Aesthetic Journey

- Local Style and Homogenizing trends: Early Medieval Sculpture in Galaganatha

- English China: Delicate Pallid Beauty

- The Beauty of 'Bilal'

- Photo Essay

- The Way of The Masters: The Great Artists of India 1100 –1900

- Striving Towards Objectivity

- The Art of Sculpting In the Contemporary Times

- An Artistic Framework for an Alternative to Ecology

- Bidriware and Damascene Work in Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art

- A Lowdown on the Print Market

- The 'bubble' and the 'wobble'

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata: June – July 2011

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

- Christie's Jewellery Auction at London, South Kensington

ART news & views

Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

Volume: 3 Issue No: 19 Month: 8 Year: 2011

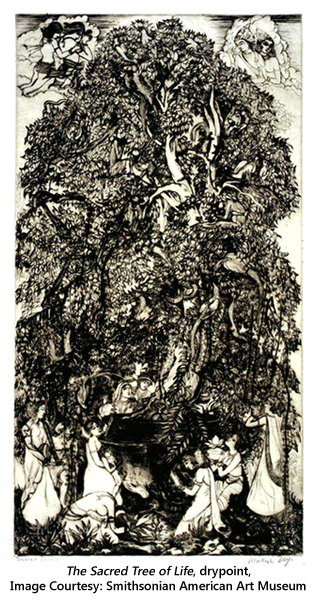

Nowadays Mukul Dey tries to keep in an artistic form by retouching drypoints decades old. He does not have the resources to engrave new plates and pull prints from them. “From 6 am to 11 am everyday, I slog to retrieve the time-worn incisions,” he says with an ironic smile and florid gestures. At 84, he hardly gives away his age, the manner bespeaking a reservoir of untapped energy rather than natural debility. He presently appealed for help, especially to UNESCO, in preserving the engraved graphics.

“Sir Muirhead Bone,  one of my teachers at the Slade in London,” he explains, pointing to a retouched engraving from 1920…the resurrected portrait, gleaming pink on the dusty copper traces in a web of hairline scorings. There are two other plates on which he has been grinding away for days: a 1916 nude done in America and an Indian rural view from the mid-1940s. The chipped table, crammed with burins, scrapers, brushes and other paraphernalia, serving him as the atelier stand, epitomizes the pervasive disorder of his life. All over the porch of his house at Santiniketan rise mounds of litter in which prints, drawings, and copies of once valuable documents can be made out. “I am defeated by this avalanche,” he wryly admits. A small pension being his only regular income on which he and his wife have to live, preserving the works which entails framing and other costly measures is beyond his means.

one of my teachers at the Slade in London,” he explains, pointing to a retouched engraving from 1920…the resurrected portrait, gleaming pink on the dusty copper traces in a web of hairline scorings. There are two other plates on which he has been grinding away for days: a 1916 nude done in America and an Indian rural view from the mid-1940s. The chipped table, crammed with burins, scrapers, brushes and other paraphernalia, serving him as the atelier stand, epitomizes the pervasive disorder of his life. All over the porch of his house at Santiniketan rise mounds of litter in which prints, drawings, and copies of once valuable documents can be made out. “I am defeated by this avalanche,” he wryly admits. A small pension being his only regular income on which he and his wife have to live, preserving the works which entails framing and other costly measures is beyond his means.

In a green 'lungi' and a towel thrown over his shoulders, he sits in a chaise-lounge, a denial (indecipherable) of the artist. With a day's growth of stubble, a powerfully built man, he has grown rather obese but retains a fairly good vision and uses only reading glasses. The spryness is amazing in view of the strokes he has had, one imprisoning him in bed for months.

The large studio, squatting back from the living quarters in one corner of the tree-shaded grounds, is a bleaker scene of desolation. Like an abandoned warehouse, it is a (indecipherable) tattered volumes and (indecipherable) in various stages of disintegration. The manual press where he ran a limited edition of his Indian Life and Legends a couple of years ago bristles with cobwebs. A silk watercolour on which he collaborated with his guru Abanindranath Tagore is merely a relic of the original.

Mukul Dey is bitter about his plight at this late point of life, and the sourness keeps breaking into his talk. He speaks of apathy of the politicians who reneged on their promises to help him, and of the Lalit Kala Akademi which is yet to use much of the material he submitted for publication. And as if to research the present he also delves into his past, evoking eventful characters: his initiation in Bengal revolutionism, draughtsmanship in London, his world travels and association with famous men. He arranged a show of Tagore's art in Calcutta after the poet's debut in Paris in 1930. Einstein gave him ungrudging sittings for a graphic portrait which the scientist later inscribed in German. Laurence Binyon wrote the introduction to My Pilgrimages to Ajanta and Bagh, a book about his cave residence at the two sites where he made copies of the decaying frescoes.

“At least 3000 pieces need immediate protection,” he says. Ranging from paintings and drawings to photographs, they include a series of engraved plates from which no impressions have been taken. He is prepared to sell them if that will insure them against an exposure to moisture, damp and dust. The output of a brilliant career, they are a mirror of the art renaissance led by Abanindranath Tagore.