- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Love of Life (that) Spills Over

- A Continuing Multiplication

- From Painting to Print

- Intimate Involvement

- Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

- (Hi)Story of the Garhi Printmaking Studios, New Delhi

- Surinder Chadda

- Ramendranath Chakravorty

- Group 8

- Mother and Child: A Screenplay

- Straddling Worlds

- A Brief History of Printmaking at Santiniketan

- Vignettes from History

- Southern Strategies

- The Forgotten Pioneer: Rasiklal Parikh

- Printmaking in the City Of Joy

- Amitabha Banerjee: His Art and Aesthetic Journey

- Local Style and Homogenizing trends: Early Medieval Sculpture in Galaganatha

- English China: Delicate Pallid Beauty

- The Beauty of 'Bilal'

- Photo Essay

- The Way of The Masters: The Great Artists of India 1100 –1900

- Striving Towards Objectivity

- The Art of Sculpting In the Contemporary Times

- An Artistic Framework for an Alternative to Ecology

- Bidriware and Damascene Work in Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art

- A Lowdown on the Print Market

- The 'bubble' and the 'wobble'

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata: June – July 2011

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

- Christie's Jewellery Auction at London, South Kensington

ART news & views

Ramendranath Chakravorty

Volume: 3 Issue No: 19 Month: 8 Year: 2011

Pioneer in modern Indian printmaking

by Soumik Nandy Majumdar

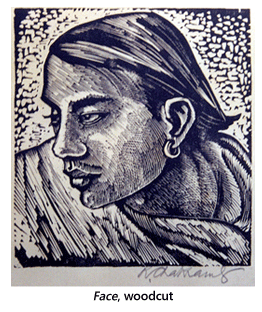

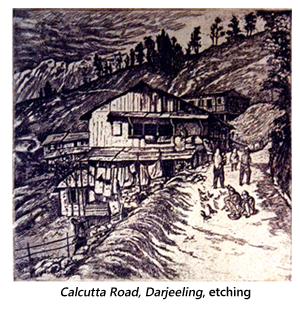

Ramendranath Chakravorty, though the name may not necessarily ring a bell among the new generation, is still reverentially remembered by many senior printmakers and artists. Sanat Kar, Lalu Prasad Shaw, Jogen Chowdhury and others recognize him as one of the key players in establishing printmaking as an immensely innovative medium within the domain of modern Indian art. A quick look at his prints reveals his natural penchant for genre art, his ability to capture the locale with all its charms, and a deep engagement with the hitherto lesser-known mediums like woodcut, etching, linocut, etc.

Ramendranath Chakravorty, though the name may not necessarily ring a bell among the new generation, is still reverentially remembered by many senior printmakers and artists. Sanat Kar, Lalu Prasad Shaw, Jogen Chowdhury and others recognize him as one of the key players in establishing printmaking as an immensely innovative medium within the domain of modern Indian art. A quick look at his prints reveals his natural penchant for genre art, his ability to capture the locale with all its charms, and a deep engagement with the hitherto lesser-known mediums like woodcut, etching, linocut, etc.

It is not altogether unnatural that the name of Ramendranath might evoke a picture of an older time and a bygone era in the history of Indian art…but there is something beyond this mere wistfulness. The era of Ramendranath was replete with the efforts and energies of dedicated artists, almost all of whom were pledged, in their own ways, to bringing Indian art into modern times. It was a time of commitment, when artists with grand ideals were rummaging around and seeking the appropriate parameters for their artistic practices. It was also a time of increasing debates around the possible premises of art pedagogy. The significance of Ramendranath Chakravorty is located in this context and certainly for more than one reason. A versatile artist, an influential teacher, and a farsighted administrator who was instrumental in bringing noteworthy changes to the art colleges, Ramendranath Chakravorty certainly deserves a reappraisal. If he had made important contributions to his times, his time too had an essential role to play in shaping him up as an artist.

and a farsighted administrator who was instrumental in bringing noteworthy changes to the art colleges, Ramendranath Chakravorty certainly deserves a reappraisal. If he had made important contributions to his times, his time too had an essential role to play in shaping him up as an artist.

Generally speaking, Ramendranath's art was informed by a dilemma typical of the period. On the one hand those times were marked by the revivalist environment with a strong swadesi bent, and on the other, in some of the individual artists at least, one could sense an increasing yearning for a wider exploration of the arts in both terms of style and technique. When you look at Ramendranath's entire oeuvre, he did in a sense reflect this duality. Quite a few works of his were done with obvious revivalist shades, and he never really gave up doing mythological and lyrical kinds of paintings in the customary idioms. Yet at the same time he craved to learn more about the art techniques prevalent outside the orbit of the Bengal School, specifically Japanese and European, and tried to work out a way past the mannered trends without being overtly an academic realist. This vacillation shows mostly in his temperas and oils. However…looking at his prints in particular…namely woodcuts, wood engravings, linocuts, etchings, drypoints and lithography, one notices the emergence of a remarkable artist with a firm approach unaffected by any kind of wavering. In this context, Benode Behari Mukherjee writes, "Initially Ramendranath was deeply attracted to the Japanese artist Hokusai. He was impressed with Hokusai's power of observation and his tenacity to keep the creative life alive even at the face of all odds. Later he found a great friend in the English artist Muirhead Bone. However, more than the artistic ideals of Hokusai or Muirhead, it was their energetic involvement that inspired Ramendranath even more. Ramendranath sincerely tried to make this stimulation absolute."1 This not only gave Ramendranath a command over the above techniques but an undeniable place in the history of modern Indian printmaking. He played the role of a pioneer in this field.

drypoints and lithography, one notices the emergence of a remarkable artist with a firm approach unaffected by any kind of wavering. In this context, Benode Behari Mukherjee writes, "Initially Ramendranath was deeply attracted to the Japanese artist Hokusai. He was impressed with Hokusai's power of observation and his tenacity to keep the creative life alive even at the face of all odds. Later he found a great friend in the English artist Muirhead Bone. However, more than the artistic ideals of Hokusai or Muirhead, it was their energetic involvement that inspired Ramendranath even more. Ramendranath sincerely tried to make this stimulation absolute."1 This not only gave Ramendranath a command over the above techniques but an undeniable place in the history of modern Indian printmaking. He played the role of a pioneer in this field.

Born in 1902 to a somewhat conservative and learned family in Tripura, Ramendranath's formal art education began when he joined the Government School of Art in 1919 leaving his conventional studies midway. Within two years he left Calcutta and reached Santiniketan to join the newly founded Kala Bhavana in 1921. It is here that he found a rather fresh and conducive environment along with a bunch of talented contemporaries like Dhirendra Krishna Deb Burman, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ardhendu Prasad Banerjee, Manindra Bhushan Gupta and others. Ramendranath had already received training from Asit Kumar Halder in Calcutta and now he got Nandalal Bose…one of the greatest artist-teachers of all times…as his mentor. Needless to say, Rabindranath Tagore was still around putting all his efforts into make Kala Bhavana an extraordinarily happening place during that time.

Ramendranath arrived at Santiniketan with an insatiable urge to learn about art, to know various mediums and hone his artistic skills. His inclination to probe new ideas and venture into uncharted lands found an uninhibited compass in such a liberated atmosphere. Alongside the knowledge of the traditional arts and crafts, Kala Bhavana's teaching program made special emphasis on nature study, asserting that nature and the objective environment is a vital and most rewarding source of our visual knowledge. Nandalal Bose motivated his pupils towards this practice. Ramendranath too was deeply moved by this when he saw how much it meant for Nandalal himself. Ramendranath later writes, "During the summer afternoons, I have often seen Nandababu, amidst dusty wind, drawn by an irresistible pull, walking along the vast stretches of khoai (parched earth), looking for the sources of his imaginations. I have noticed him; daily on his way back home he is watching everything around. The colours of the butterflies, flowers in the pasture, the huge amloki tree - he is observing the nature so intensely."2

asserting that nature and the objective environment is a vital and most rewarding source of our visual knowledge. Nandalal Bose motivated his pupils towards this practice. Ramendranath too was deeply moved by this when he saw how much it meant for Nandalal himself. Ramendranath later writes, "During the summer afternoons, I have often seen Nandababu, amidst dusty wind, drawn by an irresistible pull, walking along the vast stretches of khoai (parched earth), looking for the sources of his imaginations. I have noticed him; daily on his way back home he is watching everything around. The colours of the butterflies, flowers in the pasture, the huge amloki tree - he is observing the nature so intensely."2

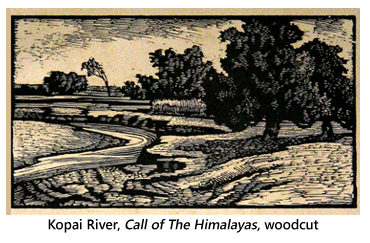

This whole question of observation implied that art should respond to the everyday realities of contemporary life and its surroundings. Ramendranath's growing interest in life and environment obliged him to take note of the minute details of tangible reality resulting in a fresh search for fitting visual forms capable of depicting things accordingly. Instead of adhering to a given idiom he created it from his own observations. Thus, in his innumerable prints, the local visual facts and subjects like Goalpara, a nearby village, the river Kopai, pastoral views of people tilling the lands, women in the fields, a group of ducks pedaling in a pond…even an ostensibly prosaic subject like variegated shadows under the trees…everything became worthy subjects for Ramendranath to draw. The mundane fact turns into a great visual delight. Ramendranath later recalled "I kept on roving in the fields, in the villages, from morning till evening…numerous sketches were piling up… I could feel that there were so many subjects accrued in nature… wherever I looked, I saw a picture, I felt I could make a composition out of any segment from this…"3

Ramendranath's beginning of genre art perhaps lies here. Progressively Ramendranath excelled in these intimate subjects. Whether in these early prints based on rural life or in the later urban subjects like Kalighat Temple, City Corner and Paris, it is quite clear that Ramendranath was not going for the picturesque at all. He was recognizing the distinguishing features of the perceived scene or object and creating his compositions based on  the immanent identities of the depicted subjects. Consequently, his works betray a great variety of compositional approaches and bypass any standardized style. This kind of artistic propensity continued to be the foundation for Ramendranath's works throughout his life.

the immanent identities of the depicted subjects. Consequently, his works betray a great variety of compositional approaches and bypass any standardized style. This kind of artistic propensity continued to be the foundation for Ramendranath's works throughout his life.

Ramendranath's experiments with the representational norms and styles were intrinsically tied up with his interest in printmaking methods. He learnt from Nandalal that each medium and technique should be addressed differently, responding to the unique problems and possibilities inherent in them. Ramendranath worked diligently to make this lesson evident in his works. In this context the role of Nandalal was unique because at that time printmaking was mostly used either for reproductive or illustrative purposes. He rescued it, as it were, from its sheer commercial trappings, and graphic art was introduced in the teaching program of Kala Bhavana right at the outset. This was possible primarily owing to the liberal and experimental ambience of Kala Bhavana itself.

Santiniketan truly was a place that attracted great exposure. By 1922 a visiting scholar like Dr Stella Kramrisch, the renowned Vienese art historian, was lecturing at Kala Bhavana on recent developments in the European art scene. Sculptor Miss Pot, Mrs Millward and other visiting artists were opening up new horizons for artists. Kala Bhavana was building up an enviable collection of art books for its library. This contact between Kala Bhavana and the outer world was a deciding factor for students like Ramendranath, particularly when French artist Madame Andre Karpeles visited Santiniketan during 1921-22 mainly to demonstrate and teach the art of wood engraving. Madame Karpeles was an expert in this technique and before long the art of engraving was introduced in Kala Bhavana for the first time. During her six months stay, Ramendranath picked up the technique as best as he could and he was soon to produce some excellent works in this medium. Around 1923 the Mexican painter Fryman, who was visiting Santiniketan, demonstrated the multi-colour woodcut process he learnt from the Japanese printmakers in Paris.  Almost immediately Ramendranath began experimenting with this new medium and in 1925 he wrote a letter to Madame Andre Karpeles in Paris requesting her to advice on how to go about colour woodcut and where to get the required materials.4

Almost immediately Ramendranath began experimenting with this new medium and in 1925 he wrote a letter to Madame Andre Karpeles in Paris requesting her to advice on how to go about colour woodcut and where to get the required materials.4

Kala Bhavana was bubbling with the new enthusiasm for printmaking when Gaganendranath Tagore donated his lithography press to Kala Bhavana and Surendranath Kar was sent to London to learn the methods of lithography and etching. Around the same time, in 1925, Nandalal Bose went to China and Japan and brought back some original prints belonging to the Far Eastern tradition. In this context it was only natural for Ramendranath to engage himself completely with these historical developments and to claim a foremost credit for launching printmaking as a viable fine art in India.

Besides being an accomplished graphic artist Ramendranath Chakravorty was also an influential teacher who inspired a whole generation of students to explore uncharted paths. After short stints at Andhra National Art Gallery (Kalashala) of Musolipatnam and Kala Bhavana, Ramendranath joined Government School of Arts, Calcutta, as the Head Assistant Teacher in 1929, during the principalship of Mukul Dey. From 1943 to 1946 he was the Officiating Principal there and more importantly he introduced the Graphics Department to the School in 1943. In addition to holding a number of other official responsibilities Ramendranath became the Principal of Government School of Arts, Calcutta in September 1949. During this time he created a landmark in his administrative career with the conversion of the School to a College in September of 1951. It was christened as Government College of Art Craft.

In 1937 Ramendranath had traveled to London for higher studies in painting at Slade School of Art, London, and studied under Sir Muirhead Bone & Eric Gill. Interestingly, while a student at Kala Bhavana long back, he had already seen some original etchings and drypoints by Sir Muirhead Bone.  Next year he had a solo show in London and it won Ramendranath wide acclaim. From this time onward (until his untimely death in 1955) he exhibited his works extensively all over the world. He also organized exhibitions of Indian artists both in India and abroad.

Next year he had a solo show in London and it won Ramendranath wide acclaim. From this time onward (until his untimely death in 1955) he exhibited his works extensively all over the world. He also organized exhibitions of Indian artists both in India and abroad.

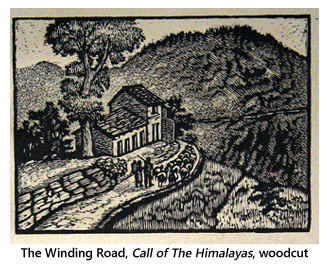

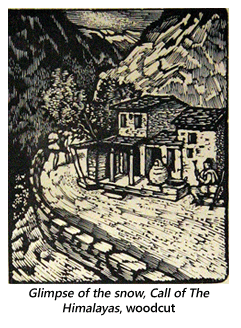

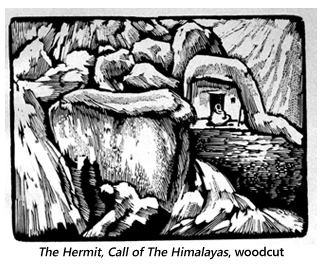

Ramendranath published his first portfolio of woodcuts called Woodcuts, with an introduction by Rabindranath Tagore, in 1931. Subsequently he kept on publishing more prints, bringing the art of printmaking close to the public and thereby popularizing it. In one such publication in a book format titled Call of the Himalayas (1943) Ramendranath displayed a hitherto unsurpassed perfection in wood engraving. Surely a masterpiece, in these works he liberally used all kinds of lines, strokes, marks and textures with a precision that is not merely technical but an ability to correspond the language of wood engraving with that of real visual experiences. It is fascinating to see how each stroke becomes a visual sign, and each engraving remains faithful to its process. This was something entirely novel after the Sahaj Path illustrations in linocuts by Nandalal Bose in 1930. Printmaking techniques henceforth became a personalized language for the artist. The enchantment of the prints by Ramendranath Chakravorty lies in this transmutation.

Notes

- Benode Behari Mukherjee, Ramendranather Shilpa-sadhana, Visva Bharati Patrika, ed. Pulin Behari Sen, Paush-Kartic 1362, Kolkata (1955), pp.163-165

- Ramendranath Chakravorty, Gurubaran (Bengali), Niriksha, Aswin 1351, Calcutta, 1944, quoted in Chitragupta,Shilpi Ramendranath Chakravorty (Bengali), Probashi, 1362, Calcutta, 1955.

- Ibid.

- Nirmalendu Das, Graphic Arts in Kala Bhavana, Nandan (Ed. by Prof. K Chakrabarti & Prof J Chakrabarti), Kala Bhavana, Santiniketan, 1985

An earlier version of this essay was published in the exhibition catalogue “Ramendranath Chakrovorty (1902 1955) : a retrospective of his graphic prints” curated Rakesh Sahni of Gallery Rasa, held at Gallery Rasa, Kolkata from 17th September to 15th October 2006.