- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Love of Life (that) Spills Over

- A Continuing Multiplication

- From Painting to Print

- Intimate Involvement

- Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

- (Hi)Story of the Garhi Printmaking Studios, New Delhi

- Surinder Chadda

- Ramendranath Chakravorty

- Group 8

- Mother and Child: A Screenplay

- Straddling Worlds

- A Brief History of Printmaking at Santiniketan

- Vignettes from History

- Southern Strategies

- The Forgotten Pioneer: Rasiklal Parikh

- Printmaking in the City Of Joy

- Amitabha Banerjee: His Art and Aesthetic Journey

- Local Style and Homogenizing trends: Early Medieval Sculpture in Galaganatha

- English China: Delicate Pallid Beauty

- The Beauty of 'Bilal'

- Photo Essay

- The Way of The Masters: The Great Artists of India 1100 –1900

- Striving Towards Objectivity

- The Art of Sculpting In the Contemporary Times

- An Artistic Framework for an Alternative to Ecology

- Bidriware and Damascene Work in Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art

- A Lowdown on the Print Market

- The 'bubble' and the 'wobble'

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Bengaluru

- Art Events Kolkata: June – July 2011

- Musings from Chennai

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Previews

- In the News

- Christie's Jewellery Auction at London, South Kensington

ART news & views

Intimate Involvement

Volume: 3 Issue No: 19 Month: 8 Year: 2011

Passionate love of Mukul Chandra Dey, for drypoint and etching.

by Satyasri Ukil

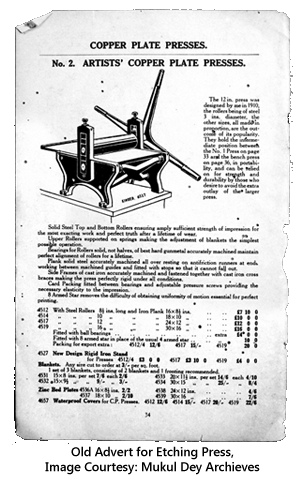

A printmaker's studio is a strange interface between art and technology, where art production is as dependent on artistic skills as on chemicals, machines, and specialized tools to engrave and scratch the image on metal plates. Here one finds needles and burins instead of brushes. And the place is full with acid mordant, beeswax, asphalt, bitumen, hotplate, French Chalk, pigments, metal plates and finally the press, with its rollers, and sets of soft yet durable felt sheets.  The entire scenario is in stark contrast to the almost feminine tenderness of a painter's studio. Yet here are produced images with wonderful chiaroscuro and bold and delicately fluid lines in multiple impressions! A printing studio may seem medieval, yet it withstands obsolescence.

The entire scenario is in stark contrast to the almost feminine tenderness of a painter's studio. Yet here are produced images with wonderful chiaroscuro and bold and delicately fluid lines in multiple impressions! A printing studio may seem medieval, yet it withstands obsolescence.

My brother Shivasri and I grew up in close proximity of one such printmaker's studio-workshop in Santiniketan during the 1960s and 70s. It belonged to artist Mukul Chandra Dey, our maternal grandfather. My earliest recollections of Dey go back to 1960, the year he returned from the UK after his more-or-less successful exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute in London. I remember his return to home primarily due to sheer bulk of luggage he brought back.

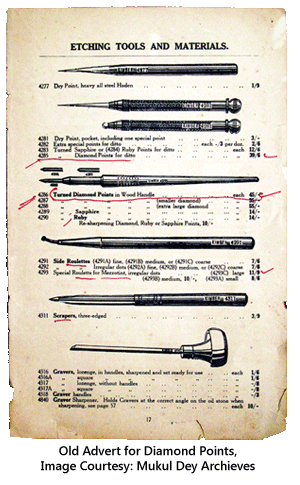

Gradually, as his travelling chests were opened, we found that the artist had purchased a supply of almost everything he needed to do printmaking for years to come, the most precious of the lot being a set of diamond-point needles, which he always carried afterwards in an old leather briefcase which had all sorts of interesting shipping liner labels stuck on its sides. These gem-points, mounted at the tips of finely crafted wooden handles, were his most precious possessions. Unfortunately, they were stolen at Santiniketan sometime later during the mid-1960s…a loss which he could never come to terms with during his life;  neither could he procure another set again.

neither could he procure another set again.

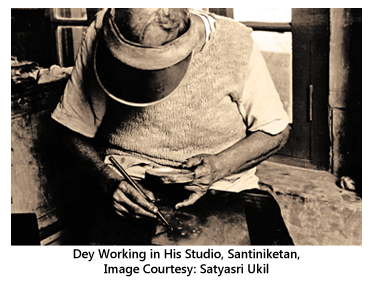

Grandfather's return from London was followed by spells of busy printmaking activity in his studio. Mukul Dey was an early riser. About seven in the morning he was ready to start in the studio. For pulling an etching or a drypoint impression he would work for days, painstakingly preparing his copper plate by beveling the edges at about 45 degrees with a flat metal file, and would polish its surfaces with a stub of special charcoal and machine oil to a mirror finish till it was spotlessly clean. Copper-plates are extremely “sensitive” he would say, and any smudge or dirt could show up in the final impression or even spoil the plate in the acid bath. Mostly he preferred to use 16 gauge copper-plates, thick and heavy, where beveling file marks were carefully scraped off and then burnished so that the edges wouldn't cut the printing paper as the plates rolled through the press.

His studio had large open windows where he fitted thick translucent paper stretched on wooden frames for soft diffused daylight, and beneath this screen the artist would place his copper-plate on a table and work on it by resting his working hand on a raised rectangular wooden support or a disc-shaped heavy leather cushion to protect the plate from unwanted fingerprints and scratches. His lines were slow, deliberate and steady. His grip on the needle was firm, yet easy. Frequent glances through the lens of a magnifying-glass on a goose-neck stand re-assured him that enough burrs were created at the right location on the image. Mukul had a craftsman's precision, and the sweat of labour went into those delicately fluid scratches. Drypoint demanded ever more of his energy and time. I can hear even now how my grandfather softly murmured to his plates and tools when they were being difficult. He used to relate to his tools and machine as if they were living beings.

With etching he was more at ease. He'd watch the width and the depth of the lines being formed in the acid bath and make careful manipulations. He was ever alert about those disturbing bubbles, which he dislodged very swiftly with the aid of a long and stiff flight-feather. As the acid starts “eating” the metal plate,  multiple air-bubbles are produced. They tend to adhere stubbornly to the scratches on a corrosion-proof etching ground, and unless these are dislodged in time, they invariably break the continuity of the line being etched.

multiple air-bubbles are produced. They tend to adhere stubbornly to the scratches on a corrosion-proof etching ground, and unless these are dislodged in time, they invariably break the continuity of the line being etched.

My grandfather did exclusively hard-ground etching; but made at least two plates of aquatint as far as I can remember. When his supply of beeswax would deplete, Mukul would replenish the stock by refining locally available honeycombs around Santiniketan, collected for him by his Santhal friends and employees. Similarly, asphalt was collected locally too.

Chemical treatments of a plate with acid and mordant were never carried out inside Dey's print studio. For this purpose, initially, he purchased the body of a small bus from a scrap-dealer. He ingeniously converted the bus into an etcher's chemical lab during the early 1940s, the same time he retired from the Government Art School of Calcutta and returned to Santiniketan. I have seen photographs of this makeshift arrangement in my childhood. Unfortunately, at the present moment of time, I could not find that precious record however hard I tried! Later on, two small adjacent rooms were built at the same location for his chemical workshop.

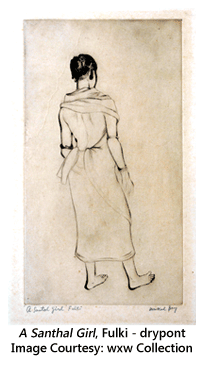

Mukul Dey was a compulsive sketcher. He, literally, made thousands of sketches from life, and many of these drawings were later used in his graphic prints. For example, I came across a pencil sketch of a tribal woman going through maize fields in Bihar in 1917, which later on was developed into a small drypoint titled Coming through the Rye. I still wonder why Mukul Dey had selected the lead lines of an old Scottish lyric to title this image of a Santhal maiden! Similarly, Dey's Hilsa Fishing, A Corner of Calcutta, On the Ganges, The Toy Seller, The Stream of Falgu, Threshing Floor, Fulki and Pearson's Bungalow at Chandipur were direct outcomes of  his sketches done from life.

his sketches done from life.

Making a print always started about fourteen hours prior to actually rolling the press. Papers were cut to size, and individual sheets were placed between two large sheets of blotting-paper that were carefully damped by a Japanese flat brush. Fresh paper clips to lift the print off the plate were made prior to each session. Dey brought with him large sheets of printing paper from the UK in 1960, while in the later years he often used slightly yellowish Japanese mulberry paper, known popularly as kozo-shi.

Next day early in the morning he would take me and my brother Shivashri to his studio for grinding powder colours like Frankfort black, French black and lamp black. The grinding was done on a white stone slab with a conical stone muller. Dey would add a few drops of strong or weak oil with his own hand, and often mix in a dash of burnt-sienna and raw umber to get a nice warm tone. At times he would even add a tiny drop of raw linseed oil in the pigment while it was ground. Raw linseed oil takes years to dry, so it gives a faint golden glow to the printed lines.

Mukul Dey almost always applied colours to plate with his bare fingers, often pushing in a little extra ink to the areas of deep etch or heavy burr. Though he had his soft leather dabbers and rollers handy he seldom used them. In 1974, as we were helping him in his major printmaking project Indian Life and Legends, I remember him often saying that one needs to ink the plates with bare finger tips to feel the lines prior to wiping and pulling the impression. He said the most important part was wiping as this way one can visualize the final print before it is actually printed. He would say that it takes years to learn wiping alone!

Near his worktable at the studio stood an iron hotplate on four legs, heated with an old English flat-wicked kerosene stove.  It had a longish chimney and mica-covered peep-window to inspect the glow. Grandfather always warmed the copper-plate a little before inking it, as well as before running it through the press, though at times he would pull a cold proof, especially during the summers.

It had a longish chimney and mica-covered peep-window to inspect the glow. Grandfather always warmed the copper-plate a little before inking it, as well as before running it through the press, though at times he would pull a cold proof, especially during the summers.

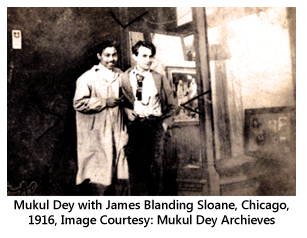

His press, which we still have with us, is a small tabletop machine devoid of gear wheels. It was purchased in New York, way back in 1916 - 17, during the time he had accompanied Rabindranath Tagore to the USA. As far as I know, this machine, which was initially established in a rented accommodation at Chitpur in Calcutta, was the earliest press on which a modern Indian artist ever started doing his own printmaking.

Mukul's press had a zinc bed going through two heavy iron rollers having twin adjustable pressure levers at both the ends, the topmost of these rollers being moved by four radiating handles. As his machine was not geared, rolling the press was always a tricky exercise. Unless a smooth and continuous movement could be maintained, the impression would spoil. Dey rolled his press till the early part of 1974, when he was about seventy-eight years of age, but during the latter half of that year the job was entrusted to me and my brother.

As mentioned earlier, 1974 was a tremendously productive time for Mukul Dey. The printing of his limited edition Indian Life and Legends was in progress at this time. Around 1967 he had suffered a cerebral stroke, and for about the next one year he lost his writing and reading abilities. But he had recovered miraculously fast! I can see from his 1966 catalogue of an exhibition in New Delhi that he had already committed to do this limited edition folio album which was to contain about twenty of his original prints. So as soon as he was well he embarked on this long-cherished project in right earnest. But the times were extremely difficult then in West Bengal especially politically. However, Dey started work undaunted.

There was political turmoil and change of government. Almost none of the printmaking raw materials, which Dey needed so badly, were available locally moreover, Dey's means were limited to a few hundred rupees, which he earned as a pension. To top it all, there was enough skepticism in the family on his ability to complete the project successfully. Turning a deaf ear to all doubts and anxieties, grandfather requested help from his friends abroad, which they did extend to the aged artist. They sent him powder colors and oil; some even brought him papers, while he had ordered a whole stock of excellent handmade backing sheets from Auroville, Pondicherry.

In the USA James Blanding Sloane and his wife Mildred were there. Though aged, they helped him with funds to procure printing materials. In UK there were Clifford Maggs and Queenie. From Switzerland Roger Renevey, Anne Marie Schumkli and Beat Aeschlimann provided much practical support to the artist. In the summers of 1973 -74 we found the studio a very busy place. Mukul Dey had advertised in the newspaper for a personal assistant and out of many applicants selected a young girl, Maya Mukherji, from Gushkara an adjacent township near Bolpur. However, for actual printmaking he preferred to train us two brothers to the craft.

In UK there were Clifford Maggs and Queenie. From Switzerland Roger Renevey, Anne Marie Schumkli and Beat Aeschlimann provided much practical support to the artist. In the summers of 1973 -74 we found the studio a very busy place. Mukul Dey had advertised in the newspaper for a personal assistant and out of many applicants selected a young girl, Maya Mukherji, from Gushkara an adjacent township near Bolpur. However, for actual printmaking he preferred to train us two brothers to the craft.

It was during this time that we got a chance to see most of his plates, which remained wrapped in tissue-paper for many years in a small steel almirah. It took weeks of careful labor to clean them properly so that the grooves could receive and retain printing ink again. Here, I must mention that only one original print that of a drypoint portrait of Abanindranath Tagore was not printed at this time, as grandfather had a number of them in his stock already.

As the printmaking was in progress at the studio, Mukul's daughter (my mother), Manjari Ukil, prepared the descriptions of the images, some of which were inspired by medieval Bengali literary works that are generally known as Mangalkavyas. These notes were being block-printed at the Navana Press of Calcutta, and proofs were constantly coming in for correction.

After the printmaking session of 1974 came to close, the studio never ever revived. Dey was aged and gradually losing hope. Many of the Indian Life and Legends albums he sent abroad to his friends came back undelivered - his friends were long dead. About forty years ago, there was no market for original prints in India, and collectors were interested to buy only the more “modern” [!] art.

I remember seeing grandfather begging Indian collectors to buy his etching and drypoint impressions for fifty rupees a piece.

Satyasri Ukil is a grandson of Mukul Chandra Dey. He works to maintain the Mukul Dey Archives in Santiniketan with the help his wife Uma and his brother Shivasri.