- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Supriya Roy and Sushobhan Adhikary

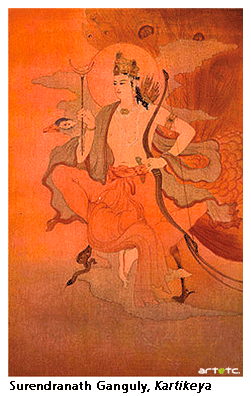

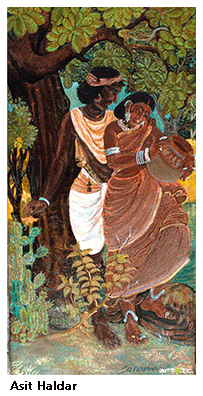

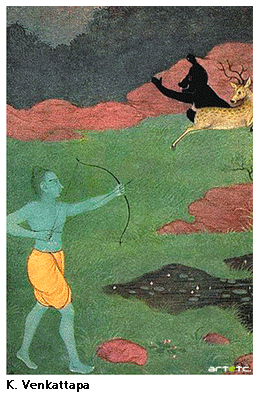

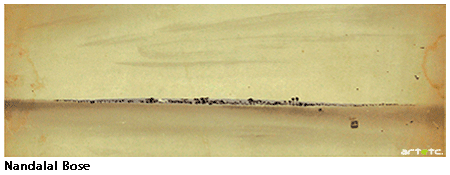

Abanindranath's role as a teacher overlapped in a number of spheres. In 1905 he was made Vice-principal of the Government Art School in Calcutta. He would work in his studio at the school and work on his paintings while his students would sit with him doing their own work, watching him and asking him for suggestions now and then. Among his first batch of students were Surendranath Ganguly (1885-1909), Nandalal Bose (1882-1966), Asit Haldar (1890-1964) and K. Venkattapa (1887-1965). Surendranath and Nandalal studied under Ishwari Prasad, a traditional painter of the Patna qualam. These various influences helped to produce the new entity of Indian painting. A traditional scholar was employed by Abanindranath to recite the Ramayana and Mahabharata to his students in order to familiarize them with the epics. They were also encouraged to paint themes from these epics.

Abanindranath's role as a teacher overlapped in a number of spheres. In 1905 he was made Vice-principal of the Government Art School in Calcutta. He would work in his studio at the school and work on his paintings while his students would sit with him doing their own work, watching him and asking him for suggestions now and then. Among his first batch of students were Surendranath Ganguly (1885-1909), Nandalal Bose (1882-1966), Asit Haldar (1890-1964) and K. Venkattapa (1887-1965). Surendranath and Nandalal studied under Ishwari Prasad, a traditional painter of the Patna qualam. These various influences helped to produce the new entity of Indian painting. A traditional scholar was employed by Abanindranath to recite the Ramayana and Mahabharata to his students in order to familiarize them with the epics. They were also encouraged to paint themes from these epics.

The second sphere of his role as guru, or master was at the southern verandah of his home at Jorasanko. Here the three brothers, Abanindranath, Samarendranath and Gaganendranath would sit and work all day. They would be visited by Abanindranath's students, other artists, Japanese artists, European art critics and art dealers. The brothers were connoisseurs of Indian art and were collectors. This milieu gradually evolved into the Vichitra art club. In the evenings there would be poetry readings, dramatic performances, musical soirees and lively discussions by the members of this club who were leading litterateurs, artists and intellectuals of the time. But during the day Vichitra was an art class and studio. Abanindranath would work with his pupils. Talented women from the Tagore household like Sunayanidevi and Pratimadevi joined as students.

The second sphere of his role as guru, or master was at the southern verandah of his home at Jorasanko. Here the three brothers, Abanindranath, Samarendranath and Gaganendranath would sit and work all day. They would be visited by Abanindranath's students, other artists, Japanese artists, European art critics and art dealers. The brothers were connoisseurs of Indian art and were collectors. This milieu gradually evolved into the Vichitra art club. In the evenings there would be poetry readings, dramatic performances, musical soirees and lively discussions by the members of this club who were leading litterateurs, artists and intellectuals of the time. But during the day Vichitra was an art class and studio. Abanindranath would work with his pupils. Talented women from the Tagore household like Sunayanidevi and Pratimadevi joined as students.

Abanindranath's active participation in the Indian Society of Oriental Art was of immense benefit to his students. The society arranged exhibitions of their works regularly; prints were made of their works. Patronage and support needed by all artists at the beginning of their careers were provided. These artists and their works were being recognized all over India; several exhibitions of their works were successfully held in some of the cities of the West. By the end of the second decade of this century Abanindranath's students were heading art schools in Lucknow, Jaipur, Lahore and Madras.

Abanindranath was no ordinary teacher taking formal classes in drawing and painting. He created an atmosphere where teacher and students would work together in a spirit of camaraderie; he was the guiding force using a variety of methods to get his point across. Each student had to be tackled differently, but what was common to all students was his love and affection for them. Once Nandalal had told Dhirendrakrishna Devvarma that the first step towards learning is respect for the teacher and the teacher's love for the student. He then spoke of his own deep feeling of respect for Abanindranath and recalled Abanindranath's love for him. When Nandalal left Calcutta for Santiniketan, the teacher felt he had lost everything and when Nandalal returned, he said he felt so exhilarated it was like having had a whole bottle of whisky!1

Dhirendranath writes of another incident. In his early years as a student, Nandalal had painted The Tapasya of Uma; he took the painting to Abanindranath, who on seeing it said, “The painting is well-executed, but there is a lack of colour, put some colour.” Early next morning, Nandalal sat with his palette and colours, wondering where to add the colour, when he heard the sound of a car; Ababindranath had come himself to stop his student from adding colour. He said, “Yesterday, after I told you to add colour, and you had left, I realized that this was a painting of Uma's austerities, the colour was within Uma, there was no need to add colour to it. Thinking of the painting, I could not sleep all nightI feared that you might add colour and so I rushed to you so early in the morning.” Nandalal recounted this incident to Dhirendranath and then added, “My guru had ordered me to add colour, so to keep his word, I added a little green stone to Uma's grass ring, and you have to look very closely to spot it!”

There was something about Abanindranath's relations with his students that touched a chord in the hearts of people who came into contact with them. William Rothenstein, on his visit to India was thus affected: “At Calcutta, at the Tagore house and at the Government School of Art I met a group of charming young artists, who gave me a touching welcome. Had I but come to India earlier, I would gladly have stayed among these students, so perplexed betwixt two traditions. Nandalal Bose, Asit Kumar Haldar and other gifted young painters, under the guidance of Abanindranath Tagore, were reviving a purely Indian tradition of painting…”2

Another student of Abanindranath was the French post-Impressionist painter, Andrée Karpelès. She recalled her experience of learning from him: “…Squatting on a low armchair, Abanindra is painting; he dips his fine Japanese brush in an ancient bowl of burnished silver; a perfect pink lotus floats on the water, beautiful and pure like the lines and colours flowing from the artist's brush. In short sentences, full of meaning, he sums up his ideas on Art; his teaching is rich and deep; the listener feels that none of Abanindra's words ought to be lost. He hands her a small sheet of paper, where he has hastily written a few sentences: The lotus of the mind (Manasapadma) is blooming because the spirit is resting on that…a work of art is the carrier of this perfume of the hidden Lotus, the unseen flowering of the mind.

Another student of Abanindranath was the French post-Impressionist painter, Andrée Karpelès. She recalled her experience of learning from him: “…Squatting on a low armchair, Abanindra is painting; he dips his fine Japanese brush in an ancient bowl of burnished silver; a perfect pink lotus floats on the water, beautiful and pure like the lines and colours flowing from the artist's brush. In short sentences, full of meaning, he sums up his ideas on Art; his teaching is rich and deep; the listener feels that none of Abanindra's words ought to be lost. He hands her a small sheet of paper, where he has hastily written a few sentences: The lotus of the mind (Manasapadma) is blooming because the spirit is resting on that…a work of art is the carrier of this perfume of the hidden Lotus, the unseen flowering of the mind.

The keener the sight, the surer the hand; the stronger the bow, the swifter the arrow flies. Lines flow unchecked from a good brush, so the perfume of the mind comes out uninterrupted through the finger tips, quick and skillful.

Manava (Mankind) is God's Manasputra (child of the mind); all our great works should be born of our Mind. So an artist from the very beginning must learn to express that which his mind sees and feels. This training of the mind should not be deferred till the artist has mastered the methods of drawing, etc. The bird must try to fly from the very beginning; otherwise it will never be able to use its wings.”3

For Abanindranath, no student was unimportant. His presence was often enough to transform a person. He has narrated an incident in his memoirs, Jorasankor Dhare (By the Side of Jorasanko): Mr. Thornton, an engineer at Martin Company, was involved with the Art Society; he was a close friend of Abanindranath. One day, before he left for England, he brought to Abanindranath his peon who he said had flair for drawing, and if Abanindranath would accept him as a student. He would pay for all expenses. The peon came the next day to attend classes. He had drawn some Calcutta streets, tramways and the like with Mr. Thornton's red and blue office pencil. The peon was asked to sit near Nandalal; Abanindranath told his students that he was a student like them and they should not look down on him. In his class, all students were equal. The poor fellow stood quietly on one side; in spite of repeated requests he kept standing. It took the teacher quite a number of days just to make him sit properly! However, he would come every day and draw pictures. He even started improving. When Mr. Thornton returned, he had to go back to his work as peon. Mr. Thornton met Abanindranath and asked him, “What have you done to my peon? Leave alone his drawing; he is now a changed man. He has amazed me with his behaviour, his good manners and his manner of talking. He is not the old peon now, he has completely changed, how did you do it?” Abanindranath replied, “Not much, I only taught him to sit!”

Rani Chanda was another of his students. To her goes the credit of patiently recording her teacher's memoirs. Without her help, these memories of Abanindranath's life would have been lost. She has left behind lively memories of Abanindranath, herself; as a teacher, he could be very strict with his students. She recalls how her brother, Mukul Dey, rather authoritarian in character, would stand sheepishly while Abanindranath would expound on the flaws in his work.

Binodebehari Mukherjee had once gone to Jorasanko to show some of his paintings to Abanindranath. He took the first painting, looked at it and asked, “What is this?” Benodebehari answered that it was a boy playing the flute. “Is he playing the flute, or is he eating a banana?” The second was of a hunter with a bow. Abanindranath told him that at the exhibition, he would also be exhibiting a painting of a hunter; “Let us see whose painting is better,” he told young Benodebehari. He refused to look at the other paintings, saying they were painted with dirty colours! He was asked to show them to Gaganendranath. The older brother first picked up the painting of the flute-player; he then asked Binode if he could play on a flute. When the boy said he could not, Gaganendranath said, “Try and blow through one, you will know where you have gone wrong.”

Rati Petit came from Bombay to Santiniketan in 1934 to study art and Manipuri dance. She later married a professor of German language in Visva-Bharati, the Buddhist Lama, Anagarika Govinda; she too became a Buddhist and adopted the name Li Gotami. She was in Santiniketan for twelve years, but it was only in 1942, that she first met Abanindranath. From her memoirs and diary notes we get more insights on Abanindranath as a teacher.4 She wrote, “Abanindranath had his own ways of teaching and they were as different from the traditional ''path'' as anyone could possibly imagine. Whatever he taught, he taught naturally and playfully, so that for me it was like learning new things from a clever little school-mate.”

During his later years, he would talk to her about art, about his strange fears and dreams. One day, in 1943, he said, “Art is like Nature. Nature is always there for those who need her. She does not throw herself at any one. If one does not feel the need to see her, she does not mind. It does not disturb her. Art is like that but in my dream Hazrat came and said: 'Teach them the REAL art.' How to teach the real thing? It took me 72 years to learn it. But he commanded me. Can I refuse...I am afraid, I tell you franklyI am afraid. Where is the strength? Where is the time? How to do it, when on all sides you students are surrounded by unreal things and unreal ideas? …Then, like a flash, it came to me last night! Hazrat came and made it plain as plain could be. Yes, I said to myself. Hazrat is right. This is not art, what I am teaching them. And then, like a cloud all the old methods vanished. I will now teach you in another way but if you do not catch it, do not blame me.”

“Hazrat” was the word Master and pupil used to denote inspiration. It had originated from a story he had told Rati about a Muslim magician who would take things from his audience and make them vanish into thin air, and then, by clapping his hands and calling out “Hazrat” three times, he would make the things reappear!

“But in fun sometimes lies real magic, and it was in such fun, perhaps, that he reached into the air and, saying “Hazrat-Hazrat-Hazrat” caught something invisible for me and, pressing it into my hand, said, 'Hold it tight. It is my very own Hazrat and I am passing it on to you…'”writes Rati.

Perhaps, of all his teaching methods, this giving of Hazrat to his students was the most precious and the one that stood by each of them in their lives as artists.

Reference:

1 Dhirendranath Devvarma, Smritipate, Santiniketan: Research Publications, 1991.

2 Rothenstein, William, Men and Memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein, 1900-1922. London: Faber & Faber, 1934

3 From the Aryan Path, 1952

4 Li Gotami 1) Abanindranath Tagore:From the Leaves of My Santiniketan Diary published in Aesthetics, A Tagore Memorial Number and 2) Abanindranath Tagore: Artist Magician in The Illustrated Weekly of India, 27 January 1952.