- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

The Onus Lies With Young India

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

It is good to see that the success of India Art Fair early this year has compelled the Western Media to sit up and take notice of the Indian Art Market again, which had definitely lagged behind in front of the surging Mandarins from China-both in the mainland as well as in the free-port of Hong Kong. The way the tone has changed over a matter of just one year is encouraging.

In June 2011, The Art Newspaper had written, “Everyone had been expecting India to be the “next big thing” after China, but so far there are fewer signs of Indian collectors shifting to international names, despite the country's huge population and 55 billionaires in 2011 (Forbes). “It's still a very closed market, the collectors aren't ready yet,” says Matt Carey-Williams of Haunch of Venison. However, Lord Poltimore of Sotheby's says that at the top there are “truly international Indian collectors, but they are very discreet”. Only now are a few private collectors opening art spaces, such as the Poddars, so perhaps watch this space.”

In June 2011, The Art Newspaper had written, “Everyone had been expecting India to be the “next big thing” after China, but so far there are fewer signs of Indian collectors shifting to international names, despite the country's huge population and 55 billionaires in 2011 (Forbes). “It's still a very closed market, the collectors aren't ready yet,” says Matt Carey-Williams of Haunch of Venison. However, Lord Poltimore of Sotheby's says that at the top there are “truly international Indian collectors, but they are very discreet”. Only now are a few private collectors opening art spaces, such as the Poddars, so perhaps watch this space.”

By February 2012 however, the India Real Time blog of The Wall Street Journal wrote, “After a roller-coaster ride, India's art market seems to be on stable ground.

At the recently-ended India Art Fair, sales were better than last year with 90% of the roughly 90 Indian and international galleries participating in the fair selling between one to four works of art.

All international galleries have vowed to come back next year, the event's organizers say, something that had not been the case last year.

While sales patterns suggest the market is showing some signs of recovery, few expect it to go back to pre-2008 levels.”

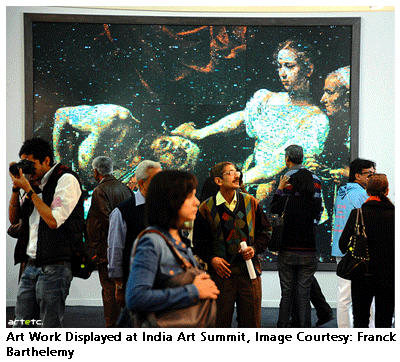

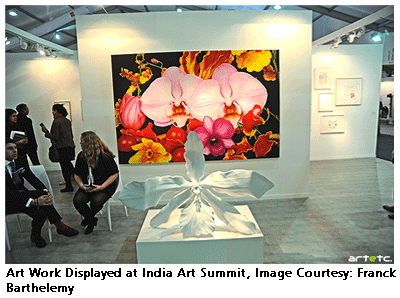

The biggest villain in the Indian art growth-story had been the 2008 downturn. WSJ writes, “Prices of contemporary and modern Indian art started soaring around a decade ago, setting the industry wheels in motion. In 2008, the first major fair of Indian art - then known as the Indian Art Summit - took place in New Delhi.

Months after that, the financial downturn hit art markets world-wide and India's wasn't spared. In that period, prices of Indian art fell by more than half.

This took a toll on several art funds that had been set up a few years earlier. When Osian's, a Mumbai-based auction house, launched its art fund in 2006, it attracted the interest of many investors.

But by the summer of 2009, when the fund was due to pay its 656 investors their returns, Osian's didn't have the money to pay them back fully. In an essay published in December, forwarded to India Real Time in response to a request for comment, Osian's founder Neville Tuli vowed to repay all investors. “Whatever the costs, this will happen very soon,” he wrote.”

However, that doesn't mean that Indian Art is back to an appreciably gung-ho state. As Neha Kirpal, the founder and director of the India Art Fair put it in the same article, “It was an artificial hype. Prices are more leveled now. That's certainly the way we want it.”

Kirpal described the overall situation as one of “stable and slow growth.” And she was not the only one to say it. Many gallerists who attended the trade fair also agreed. In the same article, Renu Modi of New Delhi's Gallery Espace which specializes in Indian Contemporary Art was quoted as saying, “It wasn't like an absolutely wow wow sale but we did sell.”

In fact as far as Indian artists are concerned, the modernists are still a lot more dependable to investors than the contemporaries. At the IAF, sales of contemporary art works priced between $50,000-$100,000 did better than those with a price tag of $200,000 or above. This, when compared to the works of the modernists like Raza, Souza and Husain shows that investors still feel more comfortable in putting their money on the predecessors of Dodiya, Kher and others.

One reason for this is the established names and the blue-chip nature of the modernists. As far as investors are concerned, they have always gone for blue-chip artists than taking a risk with the modernists. Even here, there is a clear demarcationwith the probability of a Dodiya or Kher selling higher than someone who is relatively lesser known in the international field.

However, there is a catch to this dry statistics when it comes to contemporary Indian artists. Why would the $50,000 to $100,000 range fare better than those priced at $200,000. The simple answer is affordability. But that also points at the demography of the buyers of Indian contemporary art. The market is young, and those who are buying art are also young. And experts think that this new class of buyers - young executives, entrepreneurs etc are buying art more out of love and hope rather than big-time profit. To support this, Business Today's Anumeha Chaturvedi in a March 2012 article quotes Southeby's India Director Maithili Parekh and curator Ina Puri. Parekh says, “The market is driven by young collectors who educate and acquaint themselves with art before buying.” Puri, too, talks of young collectors, many of whom believe art to be a safe investment. “There is no overnight rise or fall in prices and they have been going up gradually,” she says.

However, there is a catch to this dry statistics when it comes to contemporary Indian artists. Why would the $50,000 to $100,000 range fare better than those priced at $200,000. The simple answer is affordability. But that also points at the demography of the buyers of Indian contemporary art. The market is young, and those who are buying art are also young. And experts think that this new class of buyers - young executives, entrepreneurs etc are buying art more out of love and hope rather than big-time profit. To support this, Business Today's Anumeha Chaturvedi in a March 2012 article quotes Southeby's India Director Maithili Parekh and curator Ina Puri. Parekh says, “The market is driven by young collectors who educate and acquaint themselves with art before buying.” Puri, too, talks of young collectors, many of whom believe art to be a safe investment. “There is no overnight rise or fall in prices and they have been going up gradually,” she says.

Chaturvedi quotes young collectors in the same article, trying to understand their psyche. She writes, “But profit's not always the motive. Mumbai-based architect Ashish Shah, 32, started collecting artworks when he was in school, and has not re-sold any. His house is designed around works by Sudarshan Shetty, S. H. Raza and Shilpa Gupta. Regardless of the motive, there is no doubt that art buyers are getting younger. Consider the statistics from the recent India Art Fair in New Delhi. “Of the sales, about 40 per cent were generated by those investing in art for the first time,” says Neha Kirpal, the fair's founder and organiser.

One of those first-time buyers is Priyanka Khanna, 30, who works with a fashion magazine and bought a piece by New York-based artist Aakash Nihalani. “I have always loved art. My mother exposed us to galleries and museums across the world as children,” she says.

The bloodline worked for 34-year-old Pooja Chandra, too, albeit an acquired one. A partner with Delhi-based consultancy firm Cicero Associates, she is landscape artist Satish Chandra's daughter-in-law. Pooja's foray into the world of art coincided with her marriage, and surged with the entry of artists like Vivan Sundaram into photo prints, which are more affordable. She owns one Sundaram photo print worth Rs 1.5 lakh and is eyeing an A. Ramachandran sketch worth Rs 3 lakh. "People inherit jewellery and property, I inherited art," she says.”

Note that most of these young collectors are going for Indian names. That is significant, if one keeps in mind the most typical character of the surge in the Chinese art market. The way Qi Baishi sprinted past Pablo Picasso setting the world-record for the highest price paid for a piece of art was possible because wealthy Chinese collectors were ready to splurge upon their native artists rather than looking to West. Who can say that this phenomenon may not be repeated in India?

After all, it is not without reason that this is the market that gallerists and curators are keenly eyeing these days. Otherwise two separate interviews by two absolutely removed men in two different publications could not have been so repetitive. LiveMint's Anindita Ghose quoted the London-based Sandy Angus, who has been in the art business since the 60s and was actively involved in this year's India Art Fair, as saying, “The Indian art market is young and thriving and it's a good time to be a part of it. There's an increase in awareness in the art sector in ways that one would not have thought possible 10 years ago.” While Business Today's Anumeha Chaturvedi quoted Saffronart's COO Nish Bhutani as saying, “The Indian art market is young and thriving and it's a good time to be a part of it. There's an increase in awareness in the arts, with a wide range of exhibits taking place and information available. As a result buyers and collectors have become more informed and discerning, and look for the best quality works.”

Two people, same words. That says a lot!