- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Sandip Sarkar

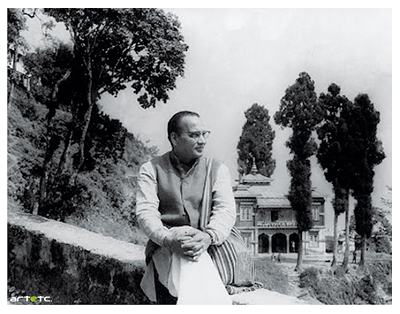

Indra Dugar was born in Jiagunj in 1918 and died in 1989 in Kolkata. He was the son of Hira Chand Dugar (1898 1951), a major painter of the early modern period of Indian Art.

Whenever I discussed with Indra Dugar about his art, he would invariably say in all humility: “my father, Hira Chand, was the melodious music. I am just a very faint distant echo. If you insist writing about my works, then you should write about his contribution in great detail. He is s a key that would, as it were, open the small lock of my humble treasure chest. “

I shall abide by Indra Dugar's express request and concentrate on the works of the father before I focus on the paintings of the son.

I still remember going to Kumar Singha Hall with my father. I was just 14 years old. It was my first exposure to actual paintings. Before it, I had only seen art reproductions in books. The Hall was dimly lit but the pictures were fabulous. My father told me most of the works were done in pure transparent watercolour. A couple of them were in gouche. He pointed out that most of them were on paper. Two were on silk. There were exquisite flower studies done in sundrenched colours with stems curling up in the posture of dance. There were hillscapes with undulating fields with trees moving to catch the mildly clouded sky in the horizon. He was a poet of lonely landscapes.

I still remember going to Kumar Singha Hall with my father. I was just 14 years old. It was my first exposure to actual paintings. Before it, I had only seen art reproductions in books. The Hall was dimly lit but the pictures were fabulous. My father told me most of the works were done in pure transparent watercolour. A couple of them were in gouche. He pointed out that most of them were on paper. Two were on silk. There were exquisite flower studies done in sundrenched colours with stems curling up in the posture of dance. There were hillscapes with undulating fields with trees moving to catch the mildly clouded sky in the horizon. He was a poet of lonely landscapes.

The Dugars are Jains and strict followers of the Tirthankaras (Saviours) who preached non violence and austerities to reach a perfect state of emancipation. Philosophically, it takes an extreme agnostic position. Both the monks and the laity practice vegetarianism.

The Dugars migrated to Murshidabad, the seat of Mughal governor of Bengal, during the tenure of Murshid Kuli Khan, more than two hundred years ago, from Rajasthan. They finally settled in Jiagunj, Murshidabad district, became engaged in trading and business. Hira Chand Dugar's father Surajmal was a successful entrepreneur like his forefathers and a very enlightened person.

According to the information that Indra Dugar gave me, Surajmal was attracted to Rajasthani miniature painting, Jain miniatures of Western India, Jaipur Frescoes, and also Haveli paintings done on walls of rich merchant houses of the Marwari clan. Surajmal was so enamoured to visual art that he did not object to Hira Chand's joining the Government School of Art and Craft, Kolkata, at the age of 16.

He worked diligently under Ishwari Prasad Verma, a great exponent of the Patna 'Kalam' (Style) of provincial Mughal Art. In 1919 Nandalal Bose took over the charge of Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan from Asit Halder, the first head of the institution who, shortly afterwards, left to join as principal of Jaipur Maharaja Art School. Bose insisted Hira Chand to quit Government Art School and join Kala Bhavan. His classmates were Dhirendra Krishna Deb Barma, Krishnakinkar Ghosh and Ardhenduprasad Banerjee.

He worked diligently under Ishwari Prasad Verma, a great exponent of the Patna 'Kalam' (Style) of provincial Mughal Art. In 1919 Nandalal Bose took over the charge of Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan from Asit Halder, the first head of the institution who, shortly afterwards, left to join as principal of Jaipur Maharaja Art School. Bose insisted Hira Chand to quit Government Art School and join Kala Bhavan. His classmates were Dhirendra Krishna Deb Barma, Krishnakinkar Ghosh and Ardhenduprasad Banerjee.

In Santiniketan Hira Chand trained rigorously under Bose and took to landscape in right earnest. Bose was by then moving away from Abanindranath Tagore's Schooling of Wash Painting and beginning to experiment with Gouche, Tempera and large Frescoes and mural on walls of Santiniketan. Hira Chand however preferred transparent watercolours.

After completing the art course in Santiniketan, Hira Chand was recalled by Surajmal to take over the family business in Jiagunj. Soon after this he lost his wife. For twenty years he was so busy that he found no time to paint.

Indra Dugar told me: “During a trip to Madhuban, Parasnath in Bihar, with my family, father accompanied us. For Jains it is a pilgrimage, an abode of Tirthankaras. You walked nine miles to reach the hilltop. There is a Jal mandir, a temple surrounded by water. We observe the rituals and I found time to paint in watercolours.”

“One day, father was stirred up by the scenic beauty. He quietly asked me, 'would you lend me your brush, paper and cakes of colour for a while? In the intervening twenty years I have forgotten how to draw and paint' I gladly gave them to him. He looked at the scene before him for a while, drew a deep breath, and began to paint. Then as if by some magic, the scene emerged and transformed the paper. From then on I watched him when he worked. He would be deeply absorbed as if in a trance. He painted hills, valleys, lakes, and rarely family events like marriage. In Rajgir, Bihar he painted Gridhakut, the temple of Keshari Ji, the Kund or hotspring and the Ban Ganga. In Udaipur he painted the Fatehsagar Lake, in Jaipur Nahargar Fort. This is the type of paintings that were exhibited in the Kumar Singh Hall, Kolkata. This was the only solo exhibition that he had during his lifetime”.

Shortly after the death of Indra Dugar I curated Hira Chand Dugar's only posthumous exposition. It was homage to Indra Dugar and his devoted love for his father. Mrs.Dugar opened up the art treasures of her father in law. It was a huge success and the Indian museum and some collectors bought paintings from the solo exhibition.

Indra Dugar told me: “My father went with my family on a pilgrimage to Palitana in Saurashtra. The temple was up the hill. While climbing he would stop to gasp for breath, sketch and paint. During the last stretch, he suddenly collapsed and died. He had a massive heart attack. It was on the 3rd May, 1951. He was only 52, I had no formal art training in an art school. In my childhood I lived in Santiniketan with my parents. Through my father, I met his mentor Nandalal Bose. When Abanindranath Tagore came on a visit, my father took me along to see him. Occasionally he would take me to Rabindranath Tagore. I frequently met his fellow students like Dhirendra Krishna Deb Verma, Ramendranath Chakraborty, Benodebehari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij. I grew up in an electrifying atmosphere. I had my first rudimentary lessons from my father. When my grandfather recalled my father to Jiagunj, I stayed back in Kolkata and got through school and completed matriculation. In college I passed Intermediate of Commerce. In 1941, I received my B.Com degree from Calcutta University. During holidays I would go to Santiniketan. Nandalal Bose, who was called 'Mastermoshai' by everyone, gave me private lessons in painting. Every time I went to Santiniketan I took some works to show to Mastermoshai. He would tell me what was good or what had gone wrong.”

“In Kolkata, Rathin Moitra, the famed painter and a founder of the 'Calcutta Group', gave me a short course on oil painting, privately. He had by then joined the Government School of Art and Craft as a mentor. I took some of my oil paintings to show to Mastermoshai. He became furious: “You have broken the taboo. You have eaten beef.” (Before independence, Indian Nationalist artists took oil painting to be a sign of foreign domination).

Lady Ranu Mukherjee took a liking to Indra Dugar. Gopal Ghosh and Rathin Moitra were the joint secretaries of Academy of Fine Arts. Indra Dugar became the arc between the two solid pillars.

He remembered Mastermoshai's flushed angry face and gave up oil painting. Most of his works are in transparent or opaque water colour, or tempera.

He told me: “The Academy of Fine Arts Annual Exhibition was held during the Christmas and new year season. Artists from every corner of India sent their works. They would receive one of the many awards. Consult their biodata you would find what I am saying is true. A great artist like Jamini Roy to major ones like M.F.Husain had won an award. Rathin Moitra, Gopal Ghose, Nirode Mazumdar and my work were displayed with a 'Not for competition' tag: but it was Mazumdar who stole the show.”

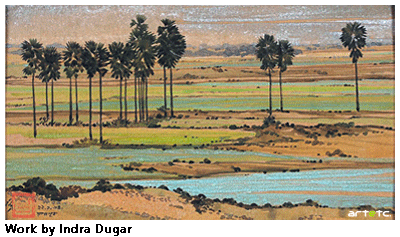

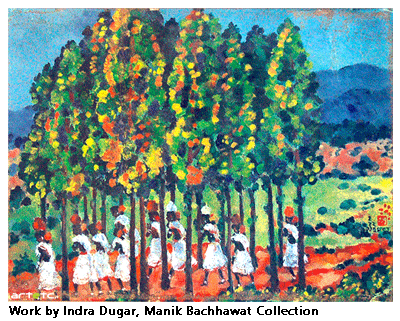

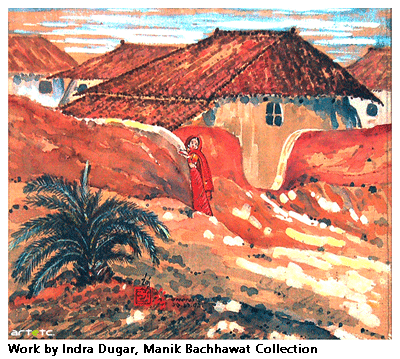

Indra Dugar was a versatile artist and very professional too in his approach to art. Many of his works are visual passion and poetry. He portrayed the atmosphere of rural life with compassion and feeling. Most of such works are done outdoors. Sometimes he did a series of colour sketches and at other times he painted directly on the spot. Indoors he would at times develop the sketches he liked the most. Through his close contacts with Rathin Moitra, Sunil Paul and Satyen Ghosal he moved out of the orbit of the neo-Bengal School. His landscapes did away with unnecessary details. From modern Indian masters like Nirode Mazumdar and mentors like Rathin Moitra he learned the technique of structuring his landscape. His colours were not as sundrenched as Hira Chand's, but a bit subdued and rather diffused. Even then his works reflect real life and glories of nature.

Indra Dugar was a versatile artist and very professional too in his approach to art. Many of his works are visual passion and poetry. He portrayed the atmosphere of rural life with compassion and feeling. Most of such works are done outdoors. Sometimes he did a series of colour sketches and at other times he painted directly on the spot. Indoors he would at times develop the sketches he liked the most. Through his close contacts with Rathin Moitra, Sunil Paul and Satyen Ghosal he moved out of the orbit of the neo-Bengal School. His landscapes did away with unnecessary details. From modern Indian masters like Nirode Mazumdar and mentors like Rathin Moitra he learned the technique of structuring his landscape. His colours were not as sundrenched as Hira Chand's, but a bit subdued and rather diffused. Even then his works reflect real life and glories of nature.

He retained the tradition that he inherited from Hira Chand. This was watercolour painting on silk. He told me: “You see, I have seen my father doing beautiful paintings on silk. Much later, I saw Manicklal Banerjee's exquisite watercolours on silk. From Banerjee I picked up the technique and experimented and adapted to my style and pictorial content.”

His oil paintings are not as strong as his work in other media. He did a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi during riot torn Noakhali district (presently in Bangladesh) just before the partition of Bengal. He told me: “I used a photograph for this realistic painting. Ramendranath Chakraborty, my father's class friend, was then the principle of Government Art School. After I finished the painting I took it to him. He studied the painting and gave me some valuable suggestions. Oil has one advantage when you compare it to other pictorial media. You can erase and change things that have burdened the work.”

Unfortunately I have not seen his mural paintings. He, I have heard, painted mural for the Jain temple in Kolkata and the Parliament House in New Delhi. In 1987 he donated forty paintings to Dr. Karan Singh for the Amar Mahal Museum, Jammu.

His works have been collected by individuals and museums around the world. In this respect a special mention must be made of new Japanese Art Association, Tokyo: The Academy of Fine Arts, Indian Museum and Raj Bhavan, Kolkata.

He participated in many international exhibitions at home and abroad. The most prestigious one was the UNESCO sponsored art exhibition, held in Paris in 1946. He received many awards, but the Academy of Fine Arts silver medal he prized the most.

The main body of his work is in either transparent or opaque watercolours. He used to paint landscapes on the spot. The images are like runways that he uses to lift off into the azure sky of his imagination. His paintings depict and do not depict, reflect and do not reflect, the actual scene. Through his bold and dancing brush strokes he reaches out behind and beyond what is on view. His paintings do not describe the actuality, illustrate a site, but launch out into the realm of poetry and music.

Through the elements of pictorial settings, he tries to reach out into regions of musical sensibility and feeing. He tries to evoke the incommunicable stuff of which our dreams and imagination are made of.

His painting Music of the Mountain does not only depict the scenic beauty of mountainous region of Darjeeling. It seems to allude a celestial music through effects of misty contrasting shades and hues. There is series of watercolours he did on river views. There are two that come immediately to mind. They depict the riverfront of Jiagunj during the day (titled: Sadarghat) and night (titled: Ratri). One can almost hear the wind blowing through the leaves and rustling waves of the river. He uses the subtlety of colour contrasts and complimentaries to reach out beyond the bounds of reality.

He had travelled around various places in the country. He depicts the Ajanta caves, the temple at Mamallapuram, the approach to the Konark temple. These works are not photographs, tourist posters are picture postcards that a traveler sends home. There are hints of inner feelings, a supple form beyond the realm of the familiar scene. Reality seems to dissolve, break off and reassemble. There is a precision in the arrangements of space and depth.

He does not break up the manifest real world but rearranges everything into his personal idiom. He does not disfigure but stylizes the parts into harmonic improvisations of visionary content. The onlooker is given an entry point with a familiar scene before the eyes. As the viewer observes, he is absorbed into an unfamiliar area of visual experience. Dugar does not carry the observer to the region of the abstract. There is a mystic hint of this. The viewer, if willing, may explore it all alone.