- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Nanak Ganguly

The complex entanglements of cultural currents that emerged with the arrival of colonialists in the eighteenth century can only be presented adequately in exhibitions like these and thus become an experience. If Historicism and even the modern, European idea of history came to non- European peoples in the nineteenth century or somebody's way of saying “not yet” to somebody else. If former simple presentation models are abandoned and the dialogues between cultures as open process, the exhibition space transforms into a site of 'European gaze'. The present site provokes a dialogue that will not question our own notion of culture and society but will also affect how we imagine ourselves. The dialogue is a continuous process: it has little to do with past concepts of edification but emerges as a vital process, a landscape where we become familiar with the changes influencing our lives. Thus signals out how an eclectic range of imagery from the changing world of colonial India became instrumental in evolving a visual language of collage and citation, which in turn, acted as a vehicle of cultural force, creating and negotiating as the sacred, the erotic, the political and the colonial modern. The very idea of historicizing carries with it some peculiarly European assumptions of disenchanted space, secular time and human sovereignty and thus Europe becomes original site of the modern. Daniells description, to cite one among the thousands will confirm that feeling of enchantment:

“The banian puts forth its shoots, which strike into the ground, and produce a rapid succession of younger trees. It is the asylum of animals …who subsist on its fruits, and are protected by its foliage. The peacock here unfolds its splendid plumage, doves nestle on the topmost boughs and monkeys live and chatter among its branches. Beneath its shade, the herdsman watches its flock, the manufacturer plies his loom, the musician touches his pipe, whilst the Bramin (sic!), abstracted from all sublunary objects, performs his solitary though not silent devotions”. And the Native is thus born.

Late scholar, art historian and Fulbright Scholar Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007) assiduously worked on the artisans in Murshidabad, Patna, Calcutta (Company paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna-1750-1850) trained and directed by the company agents in the eighteenth and nineteenth century with the zeal of a missionary and came up with a text laced with an oral tradition, which is any researcher's delight. The list of artists is a veritable who's who of company painters in nineteenth century. These painters' work constitutes European enlightenment to provide a sustained conversation between historical thinking and postcolonial perspectives and the rich legacy the colonial period has left behind in respect to artistic and cultural activity.

The art practice in Bengal flourished with the rise of Calcutta as a metropolis and its phenomenal growth as the headquarters of East India Company home to the ruling elite of the John Company. Around 1770-1850, an array of artists including the Europeans came to Calcutta to depict the aesthetic city that had grown from Job Charnock's noon day halt. Their charming portrayal of palaces and people, the melee and the melas, has left us with a rich colonial legacy of the graphic records of European Calcutta and the Black Town. Moreover, it was Calcutta more than the settlements at Bombay, Meerut, Madras or Surat that inspired them to most fevered and immortal output.

Within less than a century of Job Charnock's noon day halt on that fateful rainy afternoon of 24th August, 1690, Calcutta had grown both in beauty and importance. Travelers called Hastings's Calcutta a miniature tropical London. It was already the political, commercial and intellectual hub of India.

The colonial rule impressed its presence in Calcutta through the demarcation of new world of 'high art' and exclusive category of 'artists'. European painters and engravers who frequented India from the 1780's with a monopoly over the patronage of the emergent colonial elite, epitomized the new definition of the 'artist'. Emulating the European example, a similar identity of an artist evolved in indigenous society by the mid-nineteenth century. While the western category of 'artist was gradually loosening to accommodate Indians of middle class backgrounds, privately trained in oil painting by European tutors the category of 'artisan' included a mixed community of local painters, the draughtsmen and printmakers, who were responding equally to the pressures of westernization and new market demands. Mughal painters from Patna , Murshidabad, Lucknow who had drifted to Calcutta (as the provincial Mughal courts declined, and locus of power and patronage shifted to the British in these old seats of Nawabi culture, European painters stepped in where the traditional court artists had once thrived. The shifts in the tastes of Nawabs and the dwindling of court patronage reduced the latter to the state of 'bazaar' painters- a new colonial category) and were using western techniques, were picked up by British officials and civilians and made to learn the 'right' conventions of shading, perspective and naturalized drawing and commissioned to paint their masters' houses and servants, genres or ethnological specimens of different Indian 'trades' and 'castes'. These paintings including birds, beasts, flowers and fauna produced under the supervision of East India Company officials came to be known as 'Company School paintings'. There were painters in Chinsurah and Chandannagore who produced paintings that were 'iconographic' representation of Hindu epics, gods and goddesses, popularly known as “Dutch Bengal” or “French Bengal”- still an undefined school. These traditional gouache artists were trained to handle aquarelles, engravings and lithographs. The skills f these miniature artists were valued primarily for their adaptability to western naturalistic conventions and for the flair for their precision and detail in the pictures and diagrams ordered for them. Caught in changing demands, the traditional artist was reduced to a mere 'copyist' the result was a hybrid manner of painting.

The colonial rule impressed its presence in Calcutta through the demarcation of new world of 'high art' and exclusive category of 'artists'. European painters and engravers who frequented India from the 1780's with a monopoly over the patronage of the emergent colonial elite, epitomized the new definition of the 'artist'. Emulating the European example, a similar identity of an artist evolved in indigenous society by the mid-nineteenth century. While the western category of 'artist was gradually loosening to accommodate Indians of middle class backgrounds, privately trained in oil painting by European tutors the category of 'artisan' included a mixed community of local painters, the draughtsmen and printmakers, who were responding equally to the pressures of westernization and new market demands. Mughal painters from Patna , Murshidabad, Lucknow who had drifted to Calcutta (as the provincial Mughal courts declined, and locus of power and patronage shifted to the British in these old seats of Nawabi culture, European painters stepped in where the traditional court artists had once thrived. The shifts in the tastes of Nawabs and the dwindling of court patronage reduced the latter to the state of 'bazaar' painters- a new colonial category) and were using western techniques, were picked up by British officials and civilians and made to learn the 'right' conventions of shading, perspective and naturalized drawing and commissioned to paint their masters' houses and servants, genres or ethnological specimens of different Indian 'trades' and 'castes'. These paintings including birds, beasts, flowers and fauna produced under the supervision of East India Company officials came to be known as 'Company School paintings'. There were painters in Chinsurah and Chandannagore who produced paintings that were 'iconographic' representation of Hindu epics, gods and goddesses, popularly known as “Dutch Bengal” or “French Bengal”- still an undefined school. These traditional gouache artists were trained to handle aquarelles, engravings and lithographs. The skills f these miniature artists were valued primarily for their adaptability to western naturalistic conventions and for the flair for their precision and detail in the pictures and diagrams ordered for them. Caught in changing demands, the traditional artist was reduced to a mere 'copyist' the result was a hybrid manner of painting.

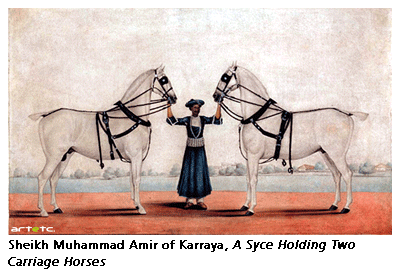

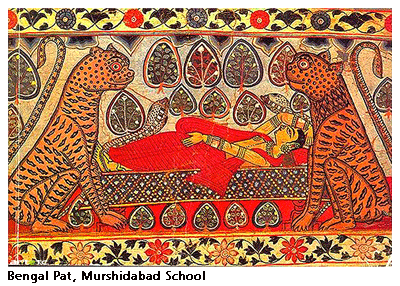

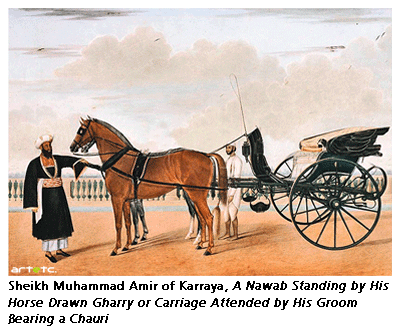

Murshidabad and Patna, till the end of the end of eighteenth century had a strong stamp of a provincial miniature style- stiff stylized figures, ornamental details and a very bright palette. A clear transition of style is evident in Murshidabad around 1790, when local painters took to copying in gouache the oils of the visiting English artist George Farrington centered around themes like the puppet Nawab Mubarak-ud- daulah at the durbar with the British resident or attending local festivals like Holi or Muharram. Among these 'company school' painters, the rarer case of artists who elevated to greater status are known for signing their pictures, as for example, E.C. Doss who painted a stereotype sets of Indian minions like barber, sircar, dewan, munshi or the more talented and distinguished like Sheikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya, pictures that reflect one of the highest points of refinement and grace in 'Company' paintings. His delicate, photo-realistic studies of the horses, horse-drawn carriages and grooms of his European patron became his distinctive trademark. It is clear from these facts that the art activity of the Company men and amateur British painters did help in the setting up of an art school along the western lines. Towards the middle of nineteenth century, art schools in Madras (1853), Calcutta (1854), Bombay (1857), and Lahore (1878) were opened and the syllabi offered were derived from London's Kensington School.

Murshidabad and Patna, till the end of the end of eighteenth century had a strong stamp of a provincial miniature style- stiff stylized figures, ornamental details and a very bright palette. A clear transition of style is evident in Murshidabad around 1790, when local painters took to copying in gouache the oils of the visiting English artist George Farrington centered around themes like the puppet Nawab Mubarak-ud- daulah at the durbar with the British resident or attending local festivals like Holi or Muharram. Among these 'company school' painters, the rarer case of artists who elevated to greater status are known for signing their pictures, as for example, E.C. Doss who painted a stereotype sets of Indian minions like barber, sircar, dewan, munshi or the more talented and distinguished like Sheikh Muhammad Amir of Karraya, pictures that reflect one of the highest points of refinement and grace in 'Company' paintings. His delicate, photo-realistic studies of the horses, horse-drawn carriages and grooms of his European patron became his distinctive trademark. It is clear from these facts that the art activity of the Company men and amateur British painters did help in the setting up of an art school along the western lines. Towards the middle of nineteenth century, art schools in Madras (1853), Calcutta (1854), Bombay (1857), and Lahore (1878) were opened and the syllabi offered were derived from London's Kensington School.

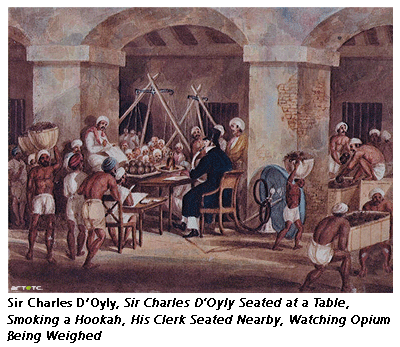

As the colonial power established its rule a number of foreign artists came to India with the hope of becoming rich overnight. These artists worked primarily in three techniques: oil on canvas, miniature painting in water colour on ivory and water colour on paper and prints made from them by engraving process. Prominent among oil painters were Tilly Kettle, Zoffany, Arthur Davies, Thomas Hickey, Francesco Ronaldi, Robert Home, William Beechy, Marshal Clakson, and Vereschagin. In addition, Ozies Humphrey, George Chinnery and Sir Charles D'oyly were notable miniature artists on ivory. Notable engravers and printmakers were Hodges, Solvyns, Soltykoff, James Mofat, Colsworthy Grant, William Simpson and the Daniells. The Great mutiny of 1857 had brought India a considerable attention in Britain and Day & Sons produced a large format book of tinted lithographs by Simpson. William Purser(1789-1852) was a painter and architect , his 'Aurangabad , from the ruins of Aurangzeb's Palace'(from a sketch by Capt. Grindlay) watercolour on paper had been engraved by C.F. Hunt in Grindlay's Scenery, Costumes and Architecture, chiefly on the Western side of India, 1830. While all the attention was being lavished on white Calcutta, the Black Town, seething with life and exotic variety, remained uncaptured on the palette. Madame Belnos, a French artist and Sir Charles D'oyly, minimized this shortfall by to a small extent. But it was Balthazar Solvyns (1760-1824), a Franco-Belgian who arrived in Calcutta in 1791 and placed it on the artistic map. A Flemish marine artist, born to a prominent merchant family in Antwerp, Calcutta was his home for thirteen years. These painters may not be a part of Dipak's thesis but couldn't resist mentioning here to give a clear picture of the art activity between 1750-1850, an area of the late scholar's specialization.

These company school engravers and painters also depicted in great detail certain aspects of the British way of life in India, especially British houses, servants, and modes of travel. In his latest piece of fiction River of Smoke Amitav Ghosh writes about George Chinnery giving a graphic account about the life of Europeans in the subcontinent”. Chinnery on the other hand, had earned fabulous sums of money while in Calcutta and his household was as chuck- muck as any in the city, with paltans of nokor- logue doing chukkers in the hallways and syces swarming in istabbuls; as for the bobachee- connah, why, it had been known to spend a hundred sicca rupees on sherbets and syllabubs, in one week….”. They also served accordingly as authentic contemporary piece of journal and as a source of information of the day. Even today D'Oyly's and other European painters including Company School artists have a wide intellectual appeal today and the complex cultural, political, social interactions between the West and the sub-continent.

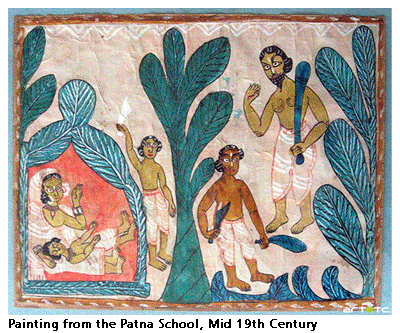

Brilliant but an amateur artist Charles D'Oyly had Indian painters to assist him. George Foster complained, “The Hindoos of this day have a slender knowledge of the rules and proportion, and none of the perspective. They are just imitators, and correct workmen; but they possess merely the glimmerings of genius.” D'Oyly, while he was stationed in Patna, set up a lithographic press to reproduce not only his own drawings but those of an enthusiastic circle of amateurs living there.

Brilliant but an amateur artist Charles D'Oyly had Indian painters to assist him. George Foster complained, “The Hindoos of this day have a slender knowledge of the rules and proportion, and none of the perspective. They are just imitators, and correct workmen; but they possess merely the glimmerings of genius.” D'Oyly, while he was stationed in Patna, set up a lithographic press to reproduce not only his own drawings but those of an enthusiastic circle of amateurs living there.

“In Patna around 1800's, the European community combined the same aloofness from Indian social life with similar interest in the picturesque, and it was this latter trait which gradually gave the Patna painters their expanded market. The city, which must have seemed at one time only a slightly more settled alternative to Murshidabad, was gradually seen to contain a new specialized demand. The Patna artists began to experiment with compositions of local Indian scenes…until about 1830 they had become perhaps the most lucrative branch of Patna paintings. The artists painted whole sets of 'Snapshots' known as 'Firkas' there were the familiar figures of the European compound: washermen, butlers returning from the market, tailors, maid servants. They portrayed the various bazaar tradesmen and craftsmen, peddlers, bangle sellers, butchers, fish-sellers, blacksmiths etc. They painted familiar town and village sights: elephants, ekkas, bullock carts, palanquins, pilgrims etc. (-Patna Painting. Mildred Archer. The Royal India Society. London, 1947). A similar demand was being met by the lithographs of Sir Charles D'Oyly, which portray the same type of the subject. Archer writes” D'Oyly's career is of great interest, for while he was posted in Patna he set up the Bihar Lithography, where he employed a Patna artist, Jairam Das, as his assistant. Several of his books portraying Indian scenes and costume, which had a wide circulation amongst Europeans in India, were made at Bihar Lithographic Press, and it is interesting to speculate how far D'Oyly may have influenced the Patna painters in their style and subject matter, or alternatively, whether they in making competent sepia drawings of the countryside and sketches for lithographs. Jairam Das received direct instructions from D'Oyly and were shown a wide range of work by Europeans. The results were electrifying. Captain Robert Smith in “Pictorial journal of travels in Hindustan from 1828 to 1833” writes “for productions of the pencil, through, I was informed, the fostering care of Sir C. D'Oyly, who has endeavoured, and with great success, to inspire the natives with some of his own pure taste and artist- like touches, instead of the hard dry manner of the Indian painters. I was much pleased with what I saw”. Captain Smith of 44th regiment was himself a talented painter as well. In the Patna Museum there is a large scrapbook of his landscape, one of which shows himself seating under a huge umbrella sketching. While he was collector in Dacca from 1808-1812 he took lessons from George Chinnery the artist, who was living there also.

D'Oyly became an opium agent in Patna in 1818 and started living in a large bungalow at Bankipore on the Ganges. Later it belonged to a Civil Surgeon whose family lived in it till 1942. D'Oyly published several of lithographs and engravings books in his lifetime The Costumes and Customs of Modern India. The European in India was published in London in 1813, followed by the Antiquities of Dacca in Dacca in 1816. In 1828 he published Tom Raw, where he refers Chinnery and Griffin as 'the ablest limner in the land', and it is clear that his style was influenced by Chinnery. Bihar Amateur Lithographic Scrapbook was published in 1828. Mildred Archer mentioned about it- “in 1830 Views of Calcutta, sketches of the new road in journey from Calcutta to Gaya was published whereas “Views of Calcutta and its Environs”, Lithographed and Published by Dickinson & Co, London was published in 1848. This was presented to the Victoria Memorial Hall by Mrs. George Lyell in memory of her husband in 1932. “It is not known whether D'Oyly had any direct contact with the better known Patna painters, though his assistant, Jairam Das, was related to many of them nor do we know whether D'Oyly actively influenced the Patna painters, but if a lithograph such as “The Nautch” (in the Bihar Lithographic Scrapbook) or some illustrations from “Costumes of India” are compared with the Patna paintings it is evident that one or the other has been influenced. It is possible that some of the stone of these lithographs were actually drawn on stone by Jairam Das and his Patna assistants from D'Oyly's drawings. …as late as 1880 Bahadur Lal II was making free copies of birds from D'Oyly and Christopher Webb-Smith's books, and in the Patna Museum there is a copy of the pictures “Ord Bhawn” or Hindu fakir from D'Oyly's costumes of India. D'Oyly may also have had a great influence on the Patna painters in their choice of subjects. his own subject matter- birds, costumes, scenes of Indian life such as gambling, music, and dancing parties, elephants, a dancing girl holding a dove- identical that of Patna pictures, and it is possible that at a time when the Patna painters were exploring the European market and trying to adapt their style to European fashions, D'Oyly and his press may well have be supplied them with a significant model” (-Mildred Archer, Patna Painting, The Royal India Society, 1947)

D'Oyly became an opium agent in Patna in 1818 and started living in a large bungalow at Bankipore on the Ganges. Later it belonged to a Civil Surgeon whose family lived in it till 1942. D'Oyly published several of lithographs and engravings books in his lifetime The Costumes and Customs of Modern India. The European in India was published in London in 1813, followed by the Antiquities of Dacca in Dacca in 1816. In 1828 he published Tom Raw, where he refers Chinnery and Griffin as 'the ablest limner in the land', and it is clear that his style was influenced by Chinnery. Bihar Amateur Lithographic Scrapbook was published in 1828. Mildred Archer mentioned about it- “in 1830 Views of Calcutta, sketches of the new road in journey from Calcutta to Gaya was published whereas “Views of Calcutta and its Environs”, Lithographed and Published by Dickinson & Co, London was published in 1848. This was presented to the Victoria Memorial Hall by Mrs. George Lyell in memory of her husband in 1932. “It is not known whether D'Oyly had any direct contact with the better known Patna painters, though his assistant, Jairam Das, was related to many of them nor do we know whether D'Oyly actively influenced the Patna painters, but if a lithograph such as “The Nautch” (in the Bihar Lithographic Scrapbook) or some illustrations from “Costumes of India” are compared with the Patna paintings it is evident that one or the other has been influenced. It is possible that some of the stone of these lithographs were actually drawn on stone by Jairam Das and his Patna assistants from D'Oyly's drawings. …as late as 1880 Bahadur Lal II was making free copies of birds from D'Oyly and Christopher Webb-Smith's books, and in the Patna Museum there is a copy of the pictures “Ord Bhawn” or Hindu fakir from D'Oyly's costumes of India. D'Oyly may also have had a great influence on the Patna painters in their choice of subjects. his own subject matter- birds, costumes, scenes of Indian life such as gambling, music, and dancing parties, elephants, a dancing girl holding a dove- identical that of Patna pictures, and it is possible that at a time when the Patna painters were exploring the European market and trying to adapt their style to European fashions, D'Oyly and his press may well have be supplied them with a significant model” (-Mildred Archer, Patna Painting, The Royal India Society, 1947)

The historian's hermeneutic, as suggested by his copious research, proceeds from an unstated and assumed premise of identification that is later disavowed in the subject- object relationship. What fundamentally rends the seriality of historical time and makes any particular moment of historical present out of joint with itself.