- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Anuradha Ghosh

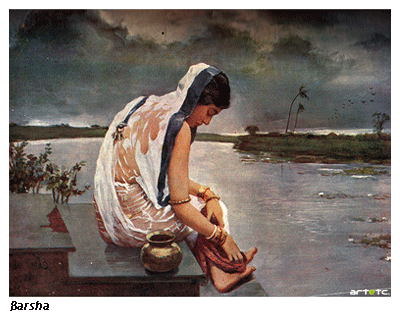

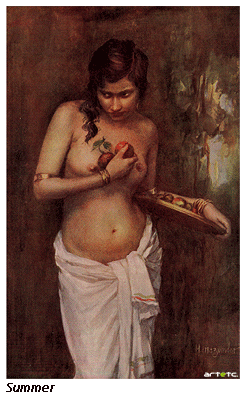

It is an encounter with moments of privacy that we are drawn into, as we view a series of works by Hemen Majumdar. For the viewer, this journey also involves moving from the point of recognizing the familiar to the discovery of its altered countenance, because of the situating of the commonplace in a subtly (often subversively) rewritten reality. Women who appear in dripping wet white sarees (Majumdar is traditionally famous for his paintings of Siktabasana Sundari, possibly because of the sheer tactile drama that he succeeds in creating with transparent folds of wet cloth on skin) are surrounded by moments of privacy that, in a sense, redefine them.

Apart from that initial sense of wonder that verisimilitude rarely fails to evoke, this visual experience can probably be explained in terms of a negotiation between two distinct modes of appreciation: one is an aesthetic engagement with the formal aspects of the paintings, the other is a need to make sense of the offered, if rather loosely-threaded, narrative that appears in the paintings. But there is also a third way in which the point of contact of some of these works can be read: it seems to have considerable potential to make voyeurs out of us, with the artist's signature blend of concealment and disclosure working on various levels. In a sense, the viewers are 'voyeured' not only by the strong erotic element present in most of Mazumdar's works, but also by the frame of isolation within which he situates his solitaries, thereby allowing the viewers a peep into that most private human moment: a silent dialogue with one's self.

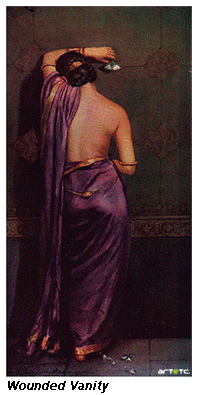

In all probability, the painter worked with the prior assumption of a heterosexual male viewership, which, in a sense, is privileged by both the story told and the devices used in its telling. Most of his paintings depict solitary female figures. Some of these lone women are also sad women, each situated in an intense moment of suffering. The uses of certain visual details as well as the choice of titles adequately uncover the reason for their suffering: this seems to be, almost always, inflicted by a man, by way of separation, betrayal and/or abandonment. For example, in the work titled Porityokta (The Abandoned) we have this woman who is presented in a recognizable gesture of distress. There is partial frontal nudity, and the interesting fact is that, in spite of her undress, she is still ornamented. Both her ornaments and her state of undress speak of the man who has just departed. The narration hinges upon such hints, remains open-ended and lends itself to diverse interpretations. For instance, we find ourselves wondering whether it is a wife or a prostitute we're looking at, and we try guessing at the circumstance of the desertion. We are allowed our own preferred version, which, however, does not compromise the hegemonic positioning of the painter, as we do see what he wants us to see- a woman defined by a man, even in his absence. The painting titled Abhiman (Wounded Vanity) also hints at a recentness of a male departure (though here it is less indicative of abandonment) with the white flower, a gift, still held loosely by the woman. Alternately, this may also be read as a tale of waiting; the man she waits for has not arrived, and the flowers meant for him are therefore torn and scattered on the floor out of frustration and 'wounded vanity'.

In all probability, the painter worked with the prior assumption of a heterosexual male viewership, which, in a sense, is privileged by both the story told and the devices used in its telling. Most of his paintings depict solitary female figures. Some of these lone women are also sad women, each situated in an intense moment of suffering. The uses of certain visual details as well as the choice of titles adequately uncover the reason for their suffering: this seems to be, almost always, inflicted by a man, by way of separation, betrayal and/or abandonment. For example, in the work titled Porityokta (The Abandoned) we have this woman who is presented in a recognizable gesture of distress. There is partial frontal nudity, and the interesting fact is that, in spite of her undress, she is still ornamented. Both her ornaments and her state of undress speak of the man who has just departed. The narration hinges upon such hints, remains open-ended and lends itself to diverse interpretations. For instance, we find ourselves wondering whether it is a wife or a prostitute we're looking at, and we try guessing at the circumstance of the desertion. We are allowed our own preferred version, which, however, does not compromise the hegemonic positioning of the painter, as we do see what he wants us to see- a woman defined by a man, even in his absence. The painting titled Abhiman (Wounded Vanity) also hints at a recentness of a male departure (though here it is less indicative of abandonment) with the white flower, a gift, still held loosely by the woman. Alternately, this may also be read as a tale of waiting; the man she waits for has not arrived, and the flowers meant for him are therefore torn and scattered on the floor out of frustration and 'wounded vanity'.

It would indeed be interesting to see the viewer (who is allowed to gaze at these private moments) as one who identifies with the extra-textual male presence and assumes a position of power in relation to the woman in the painting. We must also keep in mind that the gazer and the object of the gaze are locked together in a relationship of power, the former obviously privileged over the latter. These visual texts, therefore, seem to address the empowered voyeur, his power flowing not only from a sense of control, but also from a sense of erotic gratification. It is the apparent passivity of the object of his gaze that invests him with agency.

John Berger in Ways of Seeing observes that from 17th century (he has the European context in mind) paintings of female nudes reflected the woman's submission to the owner of both women and painting. In our present context the concept of ownership is problematised, because while the male viewer may or may not be the owner of the original painting, he definitely owns the printed reproduction of the paintings that frequently appeared in various Bangla magazines and were widely popular. This further problematises the position of the female viewer. Do we agree with Paul Messaris when he asserts (speaking about advertisements in his book Visual Persuasions) that in the female figure women see themselves as men may be seeing them, or in other words, they are invited to identify both with the person being viewed and with an implicit, opposite-sex viewer? Or is it, for them, a tale of colliding with the complex politics of collusion that implicitly exists between the male painter and the male spectator?

John Berger in Ways of Seeing observes that from 17th century (he has the European context in mind) paintings of female nudes reflected the woman's submission to the owner of both women and painting. In our present context the concept of ownership is problematised, because while the male viewer may or may not be the owner of the original painting, he definitely owns the printed reproduction of the paintings that frequently appeared in various Bangla magazines and were widely popular. This further problematises the position of the female viewer. Do we agree with Paul Messaris when he asserts (speaking about advertisements in his book Visual Persuasions) that in the female figure women see themselves as men may be seeing them, or in other words, they are invited to identify both with the person being viewed and with an implicit, opposite-sex viewer? Or is it, for them, a tale of colliding with the complex politics of collusion that implicitly exists between the male painter and the male spectator?

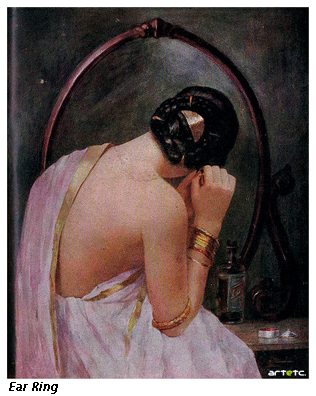

Majumdar's women frequently appear absorbed in the act of looking at themselves; their preoccupation of looking intently into a mirror, or mirror-like reflective surface (such as still water) can be read in interesting ways. In fact, the figure of the mirror-gazing woman is recurrent and familiar across cultures, and sparks off a number of diverse interpretations, ranging from vanity to auto-eroticism. In Majumdar's paintings women are typically captured as oblivious to their surroundings, looking intently into the mirror, their faces pensive, even anxious. A mirror, in a sense, creates a double of the self, and mirror-gazing can be read as a silent dialogue between the subject and her image, a practice directed at the reading of selfhood. But what if this doubled self in the mirror is appraised by an appropriated gaze? Does the woman stare at the mirror in order to understand what she looks like to the man in her life? This appropriation of the gaze of an absent male instills a sense of otherness in the reflected self within the mirror. Thus this solitary woman staring at herself is also defined by an absent man. In a sense, therefore, the painter's technique of situating his women in a space that speaks of the presence of an absent male frame, defines their individual narratives. This also relates to the theory of the dual identities of the surveyor and the surveyed in women, co-existent yet distinct, where she shifts from being herself to being an imaginary male who gazes at her (when she appraises herself critically and considers the probability of appreciation) back to the role of the passively 'surveyed', her selfhood now heavily mediated and thereby modified by the appreciative/critical gaze of the man whom she has imagined and inhabited. We feel compelled to agree with John Berger when he insists that 'To be born a woman has been to be born, within an allotted and confined space, into the keeping of men.' What he means therefore is that, the social presence of women has evolved through a process of acclimatizing oneself to this limited and limiting space, and the inexorable tutelage of men, and thus her self is split in two- 'A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself.'

Majumdar's women frequently appear absorbed in the act of looking at themselves; their preoccupation of looking intently into a mirror, or mirror-like reflective surface (such as still water) can be read in interesting ways. In fact, the figure of the mirror-gazing woman is recurrent and familiar across cultures, and sparks off a number of diverse interpretations, ranging from vanity to auto-eroticism. In Majumdar's paintings women are typically captured as oblivious to their surroundings, looking intently into the mirror, their faces pensive, even anxious. A mirror, in a sense, creates a double of the self, and mirror-gazing can be read as a silent dialogue between the subject and her image, a practice directed at the reading of selfhood. But what if this doubled self in the mirror is appraised by an appropriated gaze? Does the woman stare at the mirror in order to understand what she looks like to the man in her life? This appropriation of the gaze of an absent male instills a sense of otherness in the reflected self within the mirror. Thus this solitary woman staring at herself is also defined by an absent man. In a sense, therefore, the painter's technique of situating his women in a space that speaks of the presence of an absent male frame, defines their individual narratives. This also relates to the theory of the dual identities of the surveyor and the surveyed in women, co-existent yet distinct, where she shifts from being herself to being an imaginary male who gazes at her (when she appraises herself critically and considers the probability of appreciation) back to the role of the passively 'surveyed', her selfhood now heavily mediated and thereby modified by the appreciative/critical gaze of the man whom she has imagined and inhabited. We feel compelled to agree with John Berger when he insists that 'To be born a woman has been to be born, within an allotted and confined space, into the keeping of men.' What he means therefore is that, the social presence of women has evolved through a process of acclimatizing oneself to this limited and limiting space, and the inexorable tutelage of men, and thus her self is split in two- 'A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself.'

The private moments in Mazumdar's paintings are, therefore, rather paradoxical. The woman in question is continually watched, surveyed and judged, either by herself or an extra-textual male presence, and this meticulous creation of privacy works as an ambient factor. This embedded sense of being on display makes for an interesting and intensely observable alternation between the public and the private, the representational and the experiential.