- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by R. Siva Kumar

“A doctor is talking to you: 'This pill will erase your memory. You will forget all your suffering and all your loss. But you will also forget your entire past.' Do you swallow the pill?” (-Yann Martel)

The above sentence is from the penultimate page of Yann Martel's Beatrice and Virgil, an allegorical tale about representation of the holocaust. But the question is agonisingly existential and would be relevant to an artist in a colonised country, to immigrants or refugees in alien lands, and to men and women in many other circumstances for whom memory has become painful. They would all want to forget and let life move ahead and yet they wouldn't want to forget, or welcome amnesia.

To lose one's memory is to lose oneself, to get lost in the world just as one gets lost in an unknown city. This is what amnesia teaches us. Without memory what was once familiar becomes alien, what once belonged to you becomes estranged. Without these ties of belonging one doesn't know who one is. And not knowing who one is can drive us mad or make us depressive. The thought of dementia does not promise bliss but makes us see dread. Thus the loss of memory is not merely the loss of self but also of humanity. Without memory and our many ties with people and things we shall be turned into a thing among things.

Our world is a web of stories that connect us with others, and men with things, and hold everything together with ties of belonging and non-belonging, of oneness and difference, of friendship and hatred, of love and enmity, of fraternity and domination, of equality and hierarchy, of compassion and cruelty, of help and exploitation. And this web of stories is ever changing, one overlapping the other, one rescinding the other, or one mutating into many recensions or into other new stories, changing with every teller and every hearer, worming itself into the womb of other stories and transforming it from within or re-emerging and taking a new birth and a new identity. A living society is in short a web of living stories.

Colonialism arrived in many societies like a marauder who came to plunder but stayed on to rule. But the new emperor, and sometimes the new empress, who ascended the throne being not witty enough to understand the stories decreed them to a halt. They replaced storytellers with taxonomists who came in various guisesdressed as geologists, archaeologists, zoologists, botanists, linguists, and the like. They turned land into maps; caves, temples and mosques into monuments; objects with which one told stories of life and dreams into objects in museums; put animals into menageries and plants into herbariums; and transformed speech into grammar. In their hand life became knowledge, and life being too restless and unruly to be classified was dismantled, everythingmen, beasts, plants and thingswere detached from the web of stories and put into appropriate boxes or columns and tuned into items that could be studied and analysed without hurry.

Initially this was not totally unpleasant to the native storytellers and the readers and listeners of their stories, turning stories into taxonomic knowledge appeared to them to be the work of a marvellous magician. There was so much about themselves and their world they hadn't known, and they now looked at it as into a mirror and marvelled at what were being revealed about themselves, and they felt very pleased. In the mirror of knowledge they saw each thing in a clear scientific light that lit it up independently, and presented each thing detached from its distracting settings and without obfuscating shadows. In the stories one thing ran into another, and always hurrying forward they never stood still; their contours blurred, they lost weight and became part of shifting kaleidoscopic patterns. In contrast to this in the encyclopaedic book of knowledge, rendered in the round and in full clarity, things stood still on the page, became as substantial as the learned dons who turned the clear light of science on them and acquired a new ponderous gravity.

This was new and enchanting but not so very new either, because there were as many pundits as there were storytellers among the natives and the pundits were no less erudite and weighty then the colonial taxonomists. They too categorised and tried to hold things still within their assigned places. But they were not always successful in stemming the flow of stories, no sooner than they had given shape and clarity to a system a wave of stories would lash at them and erode their contours or cover them up with polluting sediments. Clever as they were life was never easy for the pundits; they could not avoid wrestling with the storytellers. The storytellers having been silenced, the invading taxonomists triumphed in a way the native pundits could not. In the past systems and stories intermingled and they moved together like the waters of a big flood.

But gradually the enchantment wore off and the natives discovered that with no more stories the world stood still like a city that has been cursed into sleep. The natives realised that without resuming the telling of stories they could not bring life and movement back into their world, but the storytellers had lost their voices and forgotten the art of drawing things and times together. One among those who realised this was Abanindranath Tagore. Unlike in Mughal or Rajput paintings in which life merged with the stories, in the paintings Indian painters did for the Company officials everything stood separate even when they were placed together, like cut flowers in a vase. He wanted to connect the flower to the plant, the plant to the garden, and the garden to the gardener and to the lovers who came to dally in it. But in summiting themselves to the rule of the alien taxonomists the artists had forgotten the art of narration. So Abanindranath talked of art as a magic-wand, and of awakening the sleeping beauty as the artist's mission. And with that awakening he believed that the flow of stories would start once again.

Abanindranath's career can thus be read as a slow endeavour to revivify the links between things, men and the world, to regain the native voice and to restore the flow of stories. Seen from this perspective his early paintings like the Krishnalila Series were an attempt to salvage the fragmentary remnants of ancient stories he found in old texts, and the attenuated practice of craftsmen. Into these pictures based on the padavalis and palakirtans he introduced textual inscriptions in a script reminiscent of the Persian calligraphy found in Mughal paintings and painted them using watercolour in the way he had learned from his western teachers and gilding he had learned from a native craftsman. Thus into these images based on narrative remnants from the past he infused a more hybrid and secular present in which the West was as much a reality as memories of pre-colonial India. Thus from the outset it was not a revival of stories but a revival of storytelling that he was after.

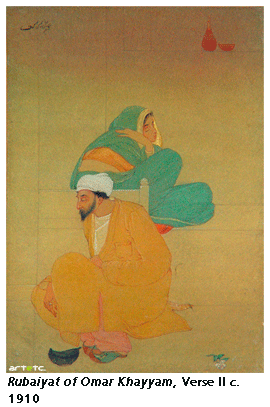

Bowing to the more secular and hybrid present he soon moved from religion and mythology to history and to styles made richer and more personal through a further amalgamation of Mughal and Japanese elements. Paradoxical as this may sound Abanindranath moved towards an individual style and voice through an assimilation of elements from various cultural pasts and the re-articulation of internalised memories. Even when he turned to history, be it episodes from Mughal history or Todd's Annals or the life of Buddha, he read it more as fable and story than as an analysis of facts or a still-life of truth. In his paintings and literary texts the line between history and literature progressively became indistinct, and emperor Shahjahan became in his imagination a close kin of the wine, love and agnostic-thought intoxicated philosopher of the Rubaiyat.

In his writings he is even more clearly a recounter of stories. Popular folk tales, literary classics, modern day annals are all made his own through re-narration. As we read or rather listen to themyes listen, because he wrote his texts in such a manner that he makes us listen even if we are only reading them to ourselvesthe story teller, through whom narrations emanating from various social and literary registers pass through and remerges transformed, begins to gain the contours of an individual sensibility. He has compared this to the transformation of sunrays into moonbeams through lunar intervention; and in both cases the transformation brings the transformer into focus.

In painting to achieve something similar he moved beyond historicist themes and representation and infused a denseness of mood and feeling into painted images, making a bird, an animal or a landscape a thing of thought and feeling more than a thing of nature. This gave his images of a tired camel or a radiant white peacock or a Shelidah landscape an evocative denseness. These pictures are not narrative but they promise stories like overcast monsoon skies that promise a rich downpour. And they make us ache for meaning and make our minds rove looking for it in our own memories.

A different kind of denseness is brought into some of his other paintings. In these the subjects are not from life but from the world of culture. Based on some visual experience or an earlier text, these images can be characterised as either representational or illustrational. But by picking on certain details and making his viewers refocus their attention, he turned them into retakes that displaced the original or familiar meanings attached to the source material. His paintings based on the actors of the popular Bengali stage and the images based on Moha-Mudgara the devotional composition attributed to Shankaracharya belong to this category. And their denseness is more intellectual than emotional, of thought rather than feeling.

While this looked like satire it was not, because it did not displace one meaning with another, or privilege one over the other, but held them together in a kind of intertextuality where primacy and judgement were at least provisionally suspended. This became clearer in his writings where the same speech was delivered in rustic patois, in affected babu-speech, and in starched literary style, and in theoretical writings where a deeply serious discourse on art was conducted in a mixture of literary and colloquial Bengali with liberal infusions of words and phrases from other languages. Such linguistic diglossia and collage of styles endorsed the enlivening co-existence of interlocutory registers rather than call for exercising a standardizing choice. And occasionally going further and signalling the final triumph of imagination, he reversed the conventional relation between plots and words, and let wordsfreed from their subservience to plotsdetermine the progress of his stories.

A collage of voices and imagination are the two elements at the heart of his storytelling. In the Arabian Nights paintings using a collage of styles and multiple registers of narration Abanindranath emerged as a triumphant storyteller creating through the series a whole web of stories. Everything he had tried and achieved piecemeal in his earlier works came together in these paintings. The Arabian Nights was not merely a text his chose to illustrate but was in itself a palimpsest of memories culled from many cultures and churned into a labyrinth of stories which he used to add depth and resonance to his readings of the present. We could call it a collage or a narrative conjoining of different times and spaces. He did this partly by painting narrative recensions where elements were changed and their relationships were sometimes inversed, and by driving home the differences by keeping other texts behind or besides his own image and in constant focus.

The fragmentary inscription of the tale into the painting on a different register or ground act as a visible sign of different narrative voices within the picture. While the inscribed text is physically conterminous with the painting and chromatically harmonises with it, it does not belong to the space of the pictured scene and is thus a simultaneous presence and not an integral part of the image. Further that the stylistic sophistication of the pictures stands in contrast to the vulgar patois of the inscribed texts reiterates the simultaneous presence of different narrative voices and cultural registers. And within the paintings themselves the rendering of different figures often carry echoes of different visual traditions. Such stylistic differences within the paintingsubtle as they areare yet another devise that gives a narrative edge to visual representation. All these taken together compel us to read these pictures as forming a web of stories which in turn is part of a larger web of stories carrying the memories of different cultures and many pasts.

While the Arabian Nights paintings contain many thematic strands the one that focuses on storytelling is of special interest to us here. The Arabian Nights is not only one large labyrinth of stories but its narrator Sheherazade like Abanindranath himself was also a victim of circumstances whose only weapon of salvage was her skills as a storyteller. That she succeeded in winning her freedom and those of her gender should have served a beacon of hope for the painter who used her stories as a trope for gaining his own narrative voice. To see how he signals this we may now turn to Abanindranath's representations of storytellers in the Arabian Nights paintings.

The first of these shows Sheherazade with her father and her younger sister. Clearly the three form a family of storytellers. It is an art that needs to be cultivated; they are each shown with a book in their hands, and the Arabian Nights also makes amply clear that she is well read. And it is a skill that is enriched through sharing and assimilation. The old Vizir and the elder daughter are masters who occupy and share the storyteller's seat; the younger daughter is by comparison a neophyte taking her first tentative steps into the world of storytelling. Each one has a different physiognomy and is also painted differently. The young daughter is a wisp of a girl on the threshold of youth, the elder one represents life in the fullness of bloom, her figure recalls that of Abanindranath's Zebunnisa and is painted with a translucent richness of colour, and the Vizir's is a grave patriarchal figure modelled with the material palpability of a Titian portrait. Their three different physiognomies and representational styles are also indicative of the three vital aspects of storytellingtruth, enchantment and wisdom.

The first of these shows Sheherazade with her father and her younger sister. Clearly the three form a family of storytellers. It is an art that needs to be cultivated; they are each shown with a book in their hands, and the Arabian Nights also makes amply clear that she is well read. And it is a skill that is enriched through sharing and assimilation. The old Vizir and the elder daughter are masters who occupy and share the storyteller's seat; the younger daughter is by comparison a neophyte taking her first tentative steps into the world of storytelling. Each one has a different physiognomy and is also painted differently. The young daughter is a wisp of a girl on the threshold of youth, the elder one represents life in the fullness of bloom, her figure recalls that of Abanindranath's Zebunnisa and is painted with a translucent richness of colour, and the Vizir's is a grave patriarchal figure modelled with the material palpability of a Titian portrait. Their three different physiognomies and representational styles are also indicative of the three vital aspects of storytellingtruth, enchantment and wisdom.

The second painting showing King Shahriyar listening to Sheherzade's narration of a story attended by Dunyazade who had been planted according to the Arabian Nights to ask for a story, for storytelling cannot begin without a listener who wishes to hear a story. However, the focus of the painting is on the effect Sheherzade's storytelling has on Shahriyar. While he is represented as the cruel and unrelenting misogynist in the text and remains so until wisdom dawns at the end here is shown as a man emotionally thawing as he listens to her story. Abanindranath represents him not as brute but as a hookah smoking aristocrat and a refined reader of books. The stories have clearly awakened old memories, and Sheherzade watches him as he, listening to her story, slips into reverie. It is an image about the transformative power or curative potency of stories.

The second painting showing King Shahriyar listening to Sheherzade's narration of a story attended by Dunyazade who had been planted according to the Arabian Nights to ask for a story, for storytelling cannot begin without a listener who wishes to hear a story. However, the focus of the painting is on the effect Sheherzade's storytelling has on Shahriyar. While he is represented as the cruel and unrelenting misogynist in the text and remains so until wisdom dawns at the end here is shown as a man emotionally thawing as he listens to her story. Abanindranath represents him not as brute but as a hookah smoking aristocrat and a refined reader of books. The stories have clearly awakened old memories, and Sheherzade watches him as he, listening to her story, slips into reverie. It is an image about the transformative power or curative potency of stories.

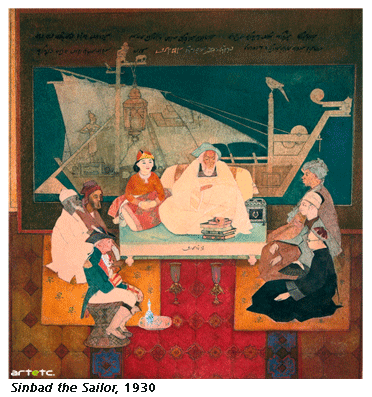

The third picture is based on the story of Sinbad the Sailor; but through a kind of reversal of it Abanindranath represents the triumph re-emergence of the native storyteller. While in the Arabian Nights story Sinbad is an adventurous world traveller who returns home to tell wondrous tales of the world to Sinbad the Landsman and other listeners. In the painting Sinbad is essentially a wise landsman and a traveller in imagination. It might be further noted that the artist's signature in this painting appears on the edge of the storyteller's seat suggesting a self-identification of the painter with the storyteller, who in fact is not one but a twosome combination of a wide-eyed boy and an erudite old man. While the eyes of the child looks into the distance that of the old narrator is turned inward, in a of similar gesture binary opposition the old storyteller has one hand resting on the pile of books before him and the other raised to his chest. The sources of his story lie both outside and within himself, and they emanate from within and travel outwards.

The third picture is based on the story of Sinbad the Sailor; but through a kind of reversal of it Abanindranath represents the triumph re-emergence of the native storyteller. While in the Arabian Nights story Sinbad is an adventurous world traveller who returns home to tell wondrous tales of the world to Sinbad the Landsman and other listeners. In the painting Sinbad is essentially a wise landsman and a traveller in imagination. It might be further noted that the artist's signature in this painting appears on the edge of the storyteller's seat suggesting a self-identification of the painter with the storyteller, who in fact is not one but a twosome combination of a wide-eyed boy and an erudite old man. While the eyes of the child looks into the distance that of the old narrator is turned inward, in a of similar gesture binary opposition the old storyteller has one hand resting on the pile of books before him and the other raised to his chest. The sources of his story lie both outside and within himself, and they emanate from within and travel outwards.

That his Sinbad is an imaginative landsman is further clarified by the manner in which the ship on the backdrop before which he sits is painted. It belongs not to the space of the storyteller and his audience which is rendered as palpable space, but to that of the inscribed text; it is flat and abstract like the written word and belongs like the text to a register folk cultural. In this world of imagination proportions do not matter, the lamp can be larger than the sailor and heavier than the mast from which it hangs, real birds can a alight on painted ships, and carved animals can come alive. The adventurer's boat is an emblem of the mind's freedom, and of the storyteller's imagination which is all that counts. And Abanindranath's Sinbad, like the painter himself, is a landsman and a storyteller who has travelled only in imagination but to whom the world comes to listen to his stories. With this image he announces the re-emergence of the native storyteller who has regained his voice and awakened the sleeping city and its web of stories.