- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

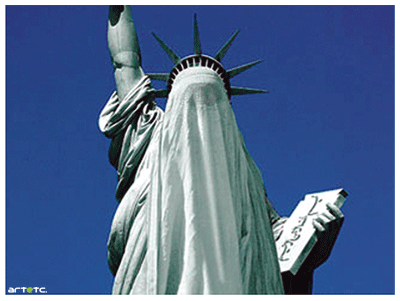

Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

As Christie's was tuning in to their big Impressionist, modern and contemporary sales in May with a confidant and solid sale of a 82-lot auction of 19th-century European art on April 23, 2012, three galleries in Vladimir Putin's Russia were jointly announcing a virtual close-down. This apparently seems queer, when one considers the fact that Russian oligarchs are the biggest drivers in the western art market.

A Reuters report on May 4 bluntly stated, 'Fearful of Putin, rich flee Russian art market' – but that may only be part of the story. The report was quoted all over the virtual space, and tongues have started wagging already against the possible state-sponsored belligerence towards anti-Putin art practices in Russia and the effect it will have on the already fumbling commercial art-scene in the country. But before we go to that, this is what exactly happened:

A Reuters report on May 4 bluntly stated, 'Fearful of Putin, rich flee Russian art market' – but that may only be part of the story. The report was quoted all over the virtual space, and tongues have started wagging already against the possible state-sponsored belligerence towards anti-Putin art practices in Russia and the effect it will have on the already fumbling commercial art-scene in the country. But before we go to that, this is what exactly happened:

Three well-established galleries, Aidan, Marat Guelman and XL, ceased commercial activities following a press conference in Moscow on April 23. Aidan will become a studio space, and Guelman and XL will transition into non-commercial ventures. Aidan, Guelman and XL are three of the pioneers behind bringing Russian contemporary art to the forefront in the country. Thus, the announcement of their virtual closure sent shockwaves through the art-fraternity in the country.

Aidan Gallery was opened in 1992 by Aidan Salakhova, one of the first spaces to brave the post-Soviet world, when an art market barely existed. Three years prior to that she had been co-founder of First Gallery, the USSR's first contemporary art gallery. An artist and art teacher in her own right, her gallery had been instrumental in turning the interest of a lot of Russian investors scattered in other European countries and investing in Western contemporary art outside Russia, back to the country.

XL, which opened in 1993 and represents a number of important contemporary artists including Salakhova, made regular appearances at the premier international art fairs like Art Basel in both Miami Beach and Switzerland, and London's Frieze. Guelman of course has been the oldest Russian gallery among the three, being established in 1990 and had always been associated with strong contemporary Russian art groups like Group AES and Oleg Kulik.

Hence a change in business strategy of these three galleries, amounting to termination of profit-making activity arising out of a need for survival in an almost constricted commercial environment should be a cause for concern.

Hence a change in business strategy of these three galleries, amounting to termination of profit-making activity arising out of a need for survival in an almost constricted commercial environment should be a cause for concern.

According to Artron.net, “The last art market boom was a huge boost to Moscow's art scene. By 2005, the art press was abuzz with news of new galleries popping up in Moscow, such as Stella, which, like some of the others, was run by the wife of an oligarch. A few years later, just before the market crash of 2008, the Winzavod art building opened in a renovated Moscow building, providing larger spaces for existing galleries like Aidan, XL, Guelman and others, and allowing new ones to open. Then, it all fell apart with the unraveling of the world's economy and, unlike in other places, like New York and London, the art market failed to recover. Ms. Salakhova said that the years 2001 to 2007 were increasingly fruitful for her gallery, and that the best years were 2005 to 2007, the height of the last boom. But the past few years have seen a huge drop off. She estimated that in 2011 she sold about half the amount, by dollar value, of what she sold in 2005. After expenses, her total profit in 2011, she said, was a mere $60,000. “We sold like $1.5 million or $2 million in 2005, and last year we sold $600, 000,” she said.”

One of the reasons Salakhova ascribed to the dwindling art scene in Moscow to a lot of collectors who have left the country: “Some of them moved to London and began collecting American and European art.” A new generation of collectors has not formed in recent years in Russia, she said. “The whole art market is not working here. After the crisis, people stopped buying art. The artists don't have studios, they don't have good education programs,” she said. “The cultural level of the country is very low now.”

ArtTactic's Global Art Market Outlook report 2012 that examines the current trends within Russia as well as the rest of the top art markets does not have much good news to give for the contemporary art scene in the country. In the summery to the report, it states, “There is a snapshot of the overall art market barometer and an individual breakdown of the welfare and performance of each region. This report includes auction analysis and the expectations for the year ahead.

“The effects of high oil prices and an accelerating Russian economy have had a significant impact on the Russian art market for the last few years. Russian collectors have made significant acquisitions of international Modern and Contemporary art, but they have also had a profound effect on the Russian art market. A wide range of Russian painters from the 19th and 20th centuries have seen rapid price appreciation. However, the market for Russian contemporary art continues to struggle to find a proper voice in the international art market.”

So what went wrong with the Russian contemporary art market scene? This is where the Reuters report becomes relevant. As it states, “Dejected by Vladimir Putin's return to power, many of Russia's glitterati have left, turning their backs on a fledgling modern art market that may now have to seek help from the state - the people who scared off its potential patrons…” and goes on to add, “…their regulars have largely left Russia, leaving their luxury market in the hands of rich bureaucrats, who neither want to draw attention to their wealth or spend on art that is often critical of the Kremlin.

So what went wrong with the Russian contemporary art market scene? This is where the Reuters report becomes relevant. As it states, “Dejected by Vladimir Putin's return to power, many of Russia's glitterati have left, turning their backs on a fledgling modern art market that may now have to seek help from the state - the people who scared off its potential patrons…” and goes on to add, “…their regulars have largely left Russia, leaving their luxury market in the hands of rich bureaucrats, who neither want to draw attention to their wealth or spend on art that is often critical of the Kremlin.

“When the richest people are bureaucrats - deputy ministers, the children of governors, the wives of mayors - then these people are ashamed of their wealth,” Gelman (owner of Gelman Gallery) said. “They would rather buy some expensive yacht far from everyone.”

“Each of the three trendsetting galleries is changing in its own way to respond to plummeting sales but they joined forces last month to communicate their message: To survive, modern art in Russia needs state support.”

“We cannot stay silent. Russian art needs help,” said Yelena Selina, whose XL Gallery is a stalwart of the Frieze, Art Basel, Fiac and Miami Basel international art fairs.

“Huge amounts of (state) money are being spent on creating a positive image of Russia. Modern art is a great calling card.”

“But her decision and that of Gelman gallery to move to a non-commercial format met with scepticism from other artists who said the state would do little more than sap the oxygen from a milieu that strives to be provocative.”

The Reuters report quotes Viktor Bondarenko, one of the country's top collectors of contemporary and other Russian art, who said that while he had not joined the stampede out of Russia, he had lost faith in reforms and sent his three children abroad.

“Modern art is the hope of the country in modernisation and innovation,” he said. “When hunters go after cats they beat them on the head with cudgels - that is about what the state and the church have done to contemporary art and hope here.”

And that is exactly what Salakhova had pointed out that a new generation of collectors is not forming in Russia and that is a huge cause for concern and if left at its own inertia, can only mean the slow but systematic dwindle of one of Europe's most potential art scene.

Which, as the British typically put it, would be such a shame.