- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Soumik Nandy Majumdar

“While thinking of Cubism I was reminded of something. When the potter turns his wheel the centre appears to be simultaneously whirling and yet remaining still.” (-Nandalal Bose in a letter written to Asit Haldar, 1922)

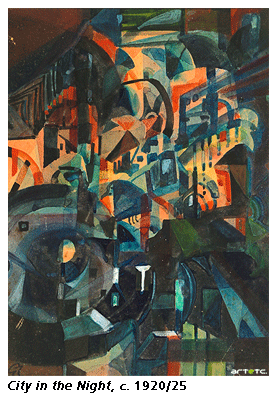

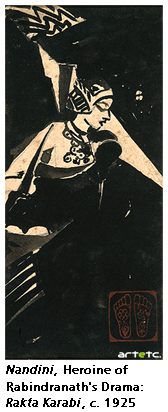

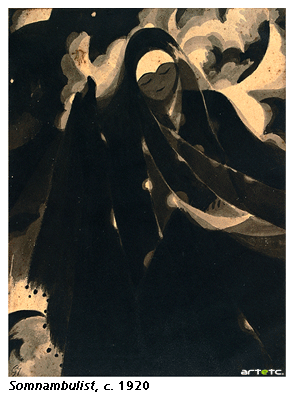

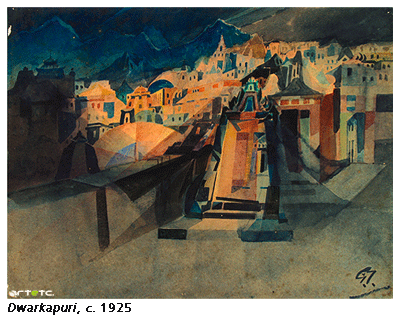

Gaganendranath Tagore (1867-1938), one of the brilliant artists and cultural activists of his time was unabashedly open to various kinds of artistic influences and sources throughout his life. Following the chronological sequence it is evident that Gaganendranath moved with great élan from one mode of pictorial style to another in different phases of his career eschewing any singular stylistic consistency but exploring a range of variables cutting across culture and time. The specific contexts of his art at various points of time also provided him with the necessary logic for each stylistic framework. Despite a certain kind of continuity in the early phase when he was producing the portraits and figure sketches with commendable accuracy or the Puri landscapes (up to 1911) or even the Chaitanya series (1911-1915) and illustrations for Jeevansmriti (1912), he was clearly responding to diverse stylistic sources like Japanese brush techniques, wash paintings, sumi-e (black ink method) and possibly Chinese ink paintings as well. The variations in brushwork attempted by him in his political cartoons at the cost of contrived elegance are also a testimony to his penchant for sourcing and consequently appropriating techniques in spite of highly empirical and local subject matters. Similarly, the so-called Cubist phase is one such group of paintings done during the period from 1921 to 1925 leading to a highly complex and personal imageries of the late paintings before he was unfortunately debilitated by cerebral paralysis.1

Gaganendranath's Cubist paintings have been a major issue for a number of writers who debated over the validity of such an influence on an Indian artist in the time of nationalist art movement catching the imagination of some of the leading artists of the time including Gaganendranath's younger brother Abanindranath Tagore. According to Dineshchandra Sen, although Abanindranath was more enthusiastic than Gaganendranath about collecting and archiving traditional Indian art, the latter did take part in removing the European paintings from the walls of their drawing rooms and replacing them with indigenous artifacts including Mughal and Rajput paintings. Historian Dineshchandra Sen wrote in the obituary, 'In divesting their house of everything of foreign origin, the brothers seem to enjoy the iconoclast's pleasure. They were also moved by patriotic zeal and they were anxious that Indian art should receive the due recognition.' 2 Gaganendranath's scathing criticism of the British colonial rule through the witty cartoons also testifies his patriotic zeal. Yet, his responses to Cubist paintings (mainly through monochrome reproductions in the beginning) are not completely unexpected since he has always been interested in the intellectual developments of the modern West and kept himself informed on a regular basis. What is interesting is to take a note of how others were reacting to this.

That Nandalal Bose was quite comfortable with Gaganendranath's cubist take is evident when he wrote, '(Gaganendranath Tagore) was inspired by the experimentalist art of modern Europe, but it did not sweep him off his feet; indeed his later paintings are splendid examples of how fresh forms and moods can be created through a complete assimilation of the alien and the familiar.'3 By emphasizing on the aspect of assimilation Nandalal Bose was openly declaring his faith in eclecticism.

When the first series of cubistic paintings by Gaganendranath were reproduced in Rupam in 1922, it seemed that he had seized the 'modernist moment' to realize his artistic vision through Cubism. Stella Kramrisch in the accompanying article significantly titled as An Indian Cubist gives credit to Gaganendranath for introducing Cubism in India albeit a different dimension.4 According to her, French Cubism “… dislocated the solid volume and rebuilt it as a continuum of movement and change.” In Gaganendranath's paintings on the other hand, she noticed a dissolution and fragmentation of the dynamic character of objects and not of the static. Further she pointed out the expressive nature of Gaganendranath's Cubism wherein 'the turbulent, hovering or pacified forces of inner experiences' were projected in terms of planes, facets and cubistic forms. Kramrisch argued that despite the influence of such a 'foreign' form Gaganendranath had internalized the peculiar cultural experience of India by turning the interpenetrating order of vertical and horizontal units into an expressive 'three-dimensional context or emotional pattern'. Though she thought that 'Indian Cubism is a paradox', she justified the case by arguing how Gaganendranath was successfully reinventing Cubism by evoking and tracing similar formal tendencies evident in the phantasmagoria of rocks and mountains in Ajanta painting. For Kramrisch it was both the cultural experience and the traditional vestiges that validated Gaganendranath's brand of Cubism. This was in tune with her assertion that even though Cubism was a European discovery, its formalist simplicity was neither unique nor significantly different from the objectives of other forms of non-illusionist art. However, she cautioned that Gaganendranath's dynamic diagonal compositions tended to set up a contradiction between the 'flowing life and lyricism of Indian art' and the 'geometric rationality' of Cubism.

When the first series of cubistic paintings by Gaganendranath were reproduced in Rupam in 1922, it seemed that he had seized the 'modernist moment' to realize his artistic vision through Cubism. Stella Kramrisch in the accompanying article significantly titled as An Indian Cubist gives credit to Gaganendranath for introducing Cubism in India albeit a different dimension.4 According to her, French Cubism “… dislocated the solid volume and rebuilt it as a continuum of movement and change.” In Gaganendranath's paintings on the other hand, she noticed a dissolution and fragmentation of the dynamic character of objects and not of the static. Further she pointed out the expressive nature of Gaganendranath's Cubism wherein 'the turbulent, hovering or pacified forces of inner experiences' were projected in terms of planes, facets and cubistic forms. Kramrisch argued that despite the influence of such a 'foreign' form Gaganendranath had internalized the peculiar cultural experience of India by turning the interpenetrating order of vertical and horizontal units into an expressive 'three-dimensional context or emotional pattern'. Though she thought that 'Indian Cubism is a paradox', she justified the case by arguing how Gaganendranath was successfully reinventing Cubism by evoking and tracing similar formal tendencies evident in the phantasmagoria of rocks and mountains in Ajanta painting. For Kramrisch it was both the cultural experience and the traditional vestiges that validated Gaganendranath's brand of Cubism. This was in tune with her assertion that even though Cubism was a European discovery, its formalist simplicity was neither unique nor significantly different from the objectives of other forms of non-illusionist art. However, she cautioned that Gaganendranath's dynamic diagonal compositions tended to set up a contradiction between the 'flowing life and lyricism of Indian art' and the 'geometric rationality' of Cubism.

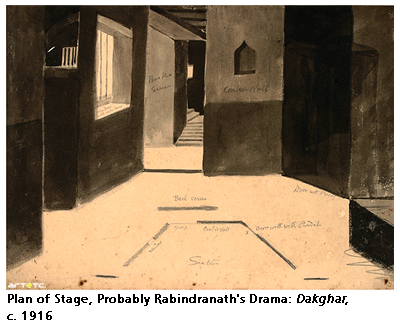

In complete contrast to Stella Kramrisch's thoughtful appreciation of Gaganendranath's cubist works, W. G. Archer in his influential account Indian and Modern Art (1959) dismissed these works by scoffing them as derivative and as product of cultural misunderstanding.5 According to him they were simply bad imitations of Picasso. For him the use of the syntax of Cubism, a product of the West, by an Indian artist was a sign of inferiority and slavish mentality. Archer in other words questioned the integrity of the artist for all the wrong reasons. Obviously, he failed to see, or did not want to acknowledge that Gaganendranath was responding to Cubist paintings as a new linguistic possibility. For Gaganendranath it was a new point of departure to address his own predilections for themes dealing with the mysterious quality of light, movement and spatial conundrum. Gaganendranath was on the threshold of a peculiar experimental modernity. The avant-garde in him discovered a whole set of possibilities in the flexible revolutionary syntax of Cubism. Truly he was the only Indian painter until 1940s who made use of the language and syntax of Cubism in his painting. Many critics have noticed close and illuminating resemblances between Gaganendranath's works and that of by European painters like Robert Delaunay, Franz Marc and Lyonel Feininger, Alexander Rodchenko and the works by the Rayonists. Needless to say that Gaganendranath was highly inspired by the original works he saw at the exhibition of water-colours and graphic prints by Bauhaus painters held in Calcutta in December 1922 sponsored by Indian Society of Oriental Art. Artists like Feininger, Johannes Itten, Kandinsky, Klee, Gerdhard Marcks and George Muche were included in this show. Not only for Gaganendranath, but for the entire artist-critic community this show symbolized the moment of 'graduation of Indian taste from Victorian naturalism to non-representational art'.6 More interestingly, Gaganendranath's Cubist fantasies, including his well-known House of Mystery, had their first public exposure alongside this Bauhaus exhibition of 1922. Hence it is obvious that his run-up to cubist works started long back in his Jeevansmriti illustrations, in his great interest in proscenium lighting for dramas and in his eagerness to pick up the delicate ink-and-brush technique from Japanese Nihonga artist Taikan. Moreover, around 1915 Gaganendranath was quietly withdrawing from Abanindranath's nationalist preoccupations and moved into a poetic fairytale world feeding on Bengali literature and performances. The cover image on the book Satbhai-Champa written by Gyanadanandini Devi is one such captivating example. A style emerging out of several fragmentations of the facets in terms of its spatiality and tonal gradations is of course suggestive of a Cubist connection but the indigenous personal cultural content of such visualization is unmistakable.

In complete contrast to Stella Kramrisch's thoughtful appreciation of Gaganendranath's cubist works, W. G. Archer in his influential account Indian and Modern Art (1959) dismissed these works by scoffing them as derivative and as product of cultural misunderstanding.5 According to him they were simply bad imitations of Picasso. For him the use of the syntax of Cubism, a product of the West, by an Indian artist was a sign of inferiority and slavish mentality. Archer in other words questioned the integrity of the artist for all the wrong reasons. Obviously, he failed to see, or did not want to acknowledge that Gaganendranath was responding to Cubist paintings as a new linguistic possibility. For Gaganendranath it was a new point of departure to address his own predilections for themes dealing with the mysterious quality of light, movement and spatial conundrum. Gaganendranath was on the threshold of a peculiar experimental modernity. The avant-garde in him discovered a whole set of possibilities in the flexible revolutionary syntax of Cubism. Truly he was the only Indian painter until 1940s who made use of the language and syntax of Cubism in his painting. Many critics have noticed close and illuminating resemblances between Gaganendranath's works and that of by European painters like Robert Delaunay, Franz Marc and Lyonel Feininger, Alexander Rodchenko and the works by the Rayonists. Needless to say that Gaganendranath was highly inspired by the original works he saw at the exhibition of water-colours and graphic prints by Bauhaus painters held in Calcutta in December 1922 sponsored by Indian Society of Oriental Art. Artists like Feininger, Johannes Itten, Kandinsky, Klee, Gerdhard Marcks and George Muche were included in this show. Not only for Gaganendranath, but for the entire artist-critic community this show symbolized the moment of 'graduation of Indian taste from Victorian naturalism to non-representational art'.6 More interestingly, Gaganendranath's Cubist fantasies, including his well-known House of Mystery, had their first public exposure alongside this Bauhaus exhibition of 1922. Hence it is obvious that his run-up to cubist works started long back in his Jeevansmriti illustrations, in his great interest in proscenium lighting for dramas and in his eagerness to pick up the delicate ink-and-brush technique from Japanese Nihonga artist Taikan. Moreover, around 1915 Gaganendranath was quietly withdrawing from Abanindranath's nationalist preoccupations and moved into a poetic fairytale world feeding on Bengali literature and performances. The cover image on the book Satbhai-Champa written by Gyanadanandini Devi is one such captivating example. A style emerging out of several fragmentations of the facets in terms of its spatiality and tonal gradations is of course suggestive of a Cubist connection but the indigenous personal cultural content of such visualization is unmistakable.

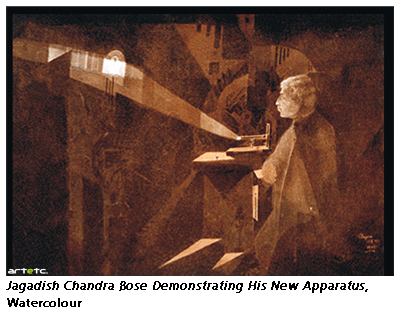

His criss-cross colour beams seemingly evoking light, quick washes of prismatic colour tones and fragmentation of the pictorial surface into several indefinite interweaving planes are detectable in his works prior to 1922. Tagore Reading His Poem at the Congress Session and Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose Demonstrating His New Apparatus are two remarkable paintings in this context in terms of their interplay and juxtaposition of light and shadow, of course without any cubist break-ups. But a lightness of being brought about by a maze of intersecting lights in varying tones and thereby evoking a sense of mystery leaving a definitive meaning less important has been a characteristic trait right at the outset. He was drawn to the prismatic experience of light almost instinctively. Hence, neither it was a mere coincidence that Gaganendranath Tagore discovered Cubism at a very significant juncture of his artistic career nor it was a compromise as Archer suspected. But it was almost like a confirmation of what he was up to in his experiments. In an interview with Kanhaiyalal Vakil in 1926 Gaganendranath says, “…………… (The new experiments) have enabled me to discover new paths and I am now expressing them better with my new technique developed out of my experiment in Cubism than I used to do with my old methods. The new technique is really wonderful as a stimulant”.7

His criss-cross colour beams seemingly evoking light, quick washes of prismatic colour tones and fragmentation of the pictorial surface into several indefinite interweaving planes are detectable in his works prior to 1922. Tagore Reading His Poem at the Congress Session and Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose Demonstrating His New Apparatus are two remarkable paintings in this context in terms of their interplay and juxtaposition of light and shadow, of course without any cubist break-ups. But a lightness of being brought about by a maze of intersecting lights in varying tones and thereby evoking a sense of mystery leaving a definitive meaning less important has been a characteristic trait right at the outset. He was drawn to the prismatic experience of light almost instinctively. Hence, neither it was a mere coincidence that Gaganendranath Tagore discovered Cubism at a very significant juncture of his artistic career nor it was a compromise as Archer suspected. But it was almost like a confirmation of what he was up to in his experiments. In an interview with Kanhaiyalal Vakil in 1926 Gaganendranath says, “…………… (The new experiments) have enabled me to discover new paths and I am now expressing them better with my new technique developed out of my experiment in Cubism than I used to do with my old methods. The new technique is really wonderful as a stimulant”.7

Much has been said regarding the influence of Picasso on Gaganendranath's works. But Gaganendranath's brand of Cubism was a far cry from Picasso's explorations. In the latter's case the emphasis on the flat surface of painting and drawing led him eventually to show that objects could be realized in all their tangibility without giving us the discreet identity of these objects. The representational and narrative strategy of image making one of the most long-standing norms of pictorial art seems to have been proved dispensable in Picasso's Cubism which was initiated by Le Demoiselles d' Avignon in 1907. For the Cubists, it was a kind of linguistic exploration, constantly moving in its analysis of how reality could be grasped. It was an art of memory not only in its approach to its subjects which it evoked by re-presenting those accumulated, remembered experiences which constituted knowledge of these subjects but also in its approach to its own pictorial language. However, with Gaganendranath the representational aspects and the spatial depth never took a back seat. Elucidating the essential differences with the European Cubists, Stella Kramrisch brought to attention Gaganendranath's strength as a narrator through his own brand of Cubism and also his ability to soften Cubism's formal severity and often ruthless geometry with 'a seductive profile, shadow or outline of human form'. 8 Perhaps, as critics have evocatively written elsewhere, the 'visible music and pulsating light' in Gaganendranath's Cubist paintings and the solicitously selected themes toss him out of the more formalist program of European Cubism and raise an important issue regarding the reception of the Western modern within the orientalist / nationalist orbit. Beside softening of angularity and rigorous linearity of the Analytic Cubism the amazingly fecund period of French Cubism from 1909 to 1912 Gaganendranath was extremely keen on addressing his preoccupations with prismatic luminosity, imaginary interiors (mysteriously illuminated by hidden artificial lights) and his enchanting fantastic fairyland. This naturally led to most experimental yet satisfactory methods of conjuring up almost surreal, interwoven, indefinite spatial depth teasing our optical habit and reminding us of someone like the Dutch artist M.C. Escher. In fact for Gaganendranath, the dynamic forms of the Futurists were more suitable than the more static Analytical Cubism. The fact that his sincere association with Cubism was rooted more in his personal imagination and literary culture rather than anything else can be argued as well. The lyricism and theatricality inbuilt in his works also on the other hand prompt us to see the dissolution of the harder side of Cubism and an invocation of a certain kind of orientalist proclivity. However, Gaganendranath's moments with Cubism played an extraordinarily important role in the normative feature of his pictorial art. He began to conceive, more effectively than before, of the pictorial components as tangible elements, to be freely arranged, to far greater extent than he could do earlier. He was no longer tied to illusionistic or naturalistic space; he was now able to arrange its elements at will, following his own ideas and visions of space and atmosphere. Hence his cubist paintings, as Benodebehari Mukherjee writes, 'leaves a lasting impression on our mind than the pressure of matter'.9

Beside an indifference to the formal implications of Analytical Cubism, Gaganendranath Tagore was effectively representing a decontextualizing tendency much favoured by many important artists of the modernist project. It is said that Cubism was a passing phase in Indian art and Gaganendranath had no follower as such. But, interestingly enough, a less discussed artist of Santiniketan who picked up from where Gaganendranath left was Prosanto Roy (1908 - 1973) a direct student of the former. A thorough study of the Roy's cubist paintings would be extremely useful to construct the history of this unique legacy.

Reference

1. Ratan Parimoo, 'Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality', Art etc. news & views, vol.3, No.11, Kolkata, July 2011

2. Dineshchandra Sen, 'As I Knew Him', 'Gaganendranath Tagore', Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta. 1972 p.11

3. Nandalal Bose, 'Gaganendranath Tagore', Gaganendranath Tagore, Rabindra Bharati Society and Assam Book Depot, Kolkata, 1964

4. Stella Kramrisch, An Indian Cubist, Rupam, vol.xi , Calcutta, July 1922

5. Quoted in Partha Mitter, 'The Triumph of Modernism', London, 2007

6. ibid

7. Ratan Parimoo, 'Gaganendranath: Painter and Personality', Art etc. news & views, vol.3, No.11, Kolkata, July 2011

8. Mitter, op.cit

9. Benodebehari Mukherjee, 'Gaganendranath Tagore', Gaganendranath Tagore, Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta. 1972, p.43.