- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- Jogen Chowdhury: Maestro par Excellence

- Company School Paintings of Calcutta, Murshidabad, Patna (1750-1850): Doctoral Thesis of Late Dipak Bhattacharya (1960-2007)

- Kalighat Pat, a Protomodern Art Tradition?

- Academic Naturalism in Art of Bengal: The First Phase of Modernity

- Under the Banyan Tree - The Woodcut Prints of 19th Century Calcutta

- The Arabian Nights and the Web of Stories

- Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

- Gaganendranath's Moments with Cubism: Anxiety of Influence

- Abanindranath as Teacher: Many Moods, Some Recollections

- Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation

- J.P. Gangooly: Landscapes on Canvas

- Defined by Absence: Hemen Majumdar's Women

- Indra Dugar: A Profile of a Painter

- The Discreet Charm of Fluid Lines!

- Delightful Dots and Dazzling Environments: Kusama's Obsessive Neurosis

- Peaceful be Your Return O Lovely Bird, from Warm Lands Back to My Window

- Shunya: A Beginning from a Point of Neutrality

- The Tagore Phenomenon, Revisited

- The Bowl, Flat and Dynamic Architecture of the BMW Museum

- Baccarat Paperweights: Handmade to Perfection

- Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Outstanding Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Retrospective of Wu Guanzhong at the Asia Society Museum

- Masterpieces from India's Late Mughal Period at the Asia Society Museum

- The Dhaka Art Summit: Emergence of Experimental Art Forms

- Many Moods of Eberhard Havekost

- Random Strokes

- Is it Putin or the Whole Russian State?

- The Onus Lies With Young India

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Preview May, 2012 – June, 2012

- In the News, May 2012

- Art Events Kolkata, April – May 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Art Bengaluru

- Musings from Chennai

- Cover

ART news & views

Gaganendranath Tagore's Satirical Drawings and Caricatures

Issue No: 29 Month: 6 Year: 2012

by Ratan Parimoo

In the theatre activities and stage performances of the Bichitra club, Gaganbabu had been fully active as an actor and stage designer. An interest in the 'comic' and 'comedy', as contents of a play and challenging assignments for an actor would have been immediate inspirational stimulants. This brings us to the predecessor writers on the 'comic', which are social satire, the playwrights of comedies and staging of farces. The sources for Gaganendranath's caricatures were his own responses to Bengali society of his generation. But there are precedents by social reformers exposed to western education as well as well as writers of plays to be performed on stage i.e. farces for theatre.

Satirical plays in the context of Gaganendranath's caricatures connect with the best farcical play of Jyotindranath Tagore, first titled Eman Karma Ar Kabo Na, I won't do such a deed again, (1977), later changed to Alik Babu, The False Baboo, 1900. It had been performed with a signal success. An immediate phase of theatrical development which certainly influenced Gaganendranath, are the plays written and performances directed by Girish Ghosh (1844-1911) at the turn of the 19th century. Utpal Dutt had tremendous admiration for Girish Ghosh's contribution to contemporary Indian theatre rather than the narrow negative opinion the Bengali literary critic, Sukumar Sen, had of him. Gaganendranath's criticism in his satirical drawing is of a different category than the Hindu reformers who took to European destructive reformation. The latter view was actually held by Vivekananda.

The following quotation from Vivekananda, selected by Utpal Dutt, would also suit Gaganendranath's caricatures. Vivekananda was critical of the copper-bottomed educated pillars of the society whose one ambition was to be blessed by the English Government with a responsible job. The quotation is as follows: “You think yourselves highly educated. What nonsense have you learnt? Getting by heart the thoughts of others in a foreign language and stuffing your brain with them and taking some university degrees you consider yourselves educated? Fie upon you! Is this education? What is the goal of your education? Either a clerkship, or being a roguish lawyer, or at the most, deputy magistracy which is another form of clerkship mist that all”. (See Gaganendranath's drawing satirizing 'university'). I quote from the only written statement left by Gaganendranth in the preface for Virupa Vajra (Birup Bajra) Strange Thunderbolt (1917), “When deformities grow unchecked, but are cherished by blind habit, it becomes the duty of the artist to show that they are ugly and vulgar and therefore abnormal”. J.C. Bose, the great contemporary scientist was the subject of one of Gaganendranth's drawings, despite his intimacy with the artist. Seeing the cartoon Bose said: “Gaganendranth's cartoons are not the sour delineation of a cynic but scenes which must have wronged the artist's soul with sorrow”.2

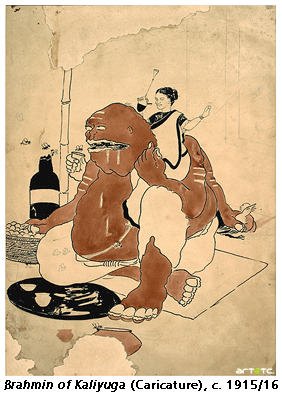

What was the status of pictorial satirization before Gaganendranath? The pictorialization of social satire had already been initiated in the visual medium by the Kalighat painters. Kalighat painters could easily adopt facets of contemporary life simultaneously with religious Icons, but naïve folk painters did not realize that the 'style' of their language did not have the expressiveness for the imageries of the 'comic'.

I presume that Gaganbabu along with other Bengali intellectuals of the time would be aware of such satirical weekly journals as the German SIMPLICISSIMUS, which regularly published (between 1896 and 1926) serious satirical drawings of prestigious artists (including Expressionists). It is considered to be one of the greatest picture magazines in the history of Journalism, which “appears in retrospect as a monument of German culture in the first half of the 20th century”,3 Gaganendranath's drawings are closer to Rudolf Wilke, whose drawings were published between 1900 and 1908. George Grosz's drawings were published from 1916 onwards with which Gaganbabu would not be so familiar. Both are exact contemporaries. The comparison with Daumier the French mid 19th century realist painter and pioneer political caricaturist in the medium of lithography is justified. Gaganbabu adopted the same technique as well as the coining of captions in pithy phrases.4

Birupa Bajra, Strange Thunderbolts and Adbhut Lok, Realm of Absurd, both these sets of caricatures were published in 1917 and are among the earliest such satirical paintings by Gaganendranath. A careful observation would reveal a remarkable sophistication of style, because of which it is possible to link them with Gaganendranath's Chaitanya series, most of which had been completed by 1914. The use of thin wirey lines going over the surface of the paper as well as large patches of black, not only shows Gaganendranath's sensitivity for surface design, but also is an attempt to give them a quality like Aubery Beardsley's much acclaimed illustrations.5

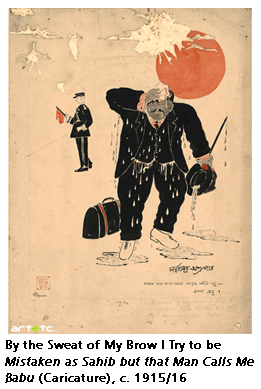

By babu we should not necessarily imply all middle class Bengalis as perceived by the British colonial administrators, or babu as a section of the Bengali middle class who were looked at as the 'other' or 'them' and who thus deserved to be severely criticized by the enlightened middle class. I think that the satirizing of the 'babu' is also part of the efforts of the middle class towards self-criticism, if not leading to social improvement but certainly to face the facts and laugh at human weakness.6 The babu's mentality of looking like and being accepted as a Gora or white sahib has been satirized in several witty drawings by Gaganendranath. This made him exclaim that 'By the sweat of my brow I tried to be mistaken for a sahib, but still that man called me Babu'.

A Noble Man

The Maharaja of Bardhman has been adopted as the archetypal rich Bengali. His natural bulkiness provides the comic imagery, elevated as an icon placed on a pedestal. Needy hands extended in front of him are shooed off by brandishing a stick held in his left hand. On his backside is depicted his wealth as heaps of coins, vulgarly spent on festivals, prostitutes (suggested by the female hand) and psychophants, (symbolized by the eagles). It is executed neatly in the same style of thin wiry lines.

Pyare Mian

The drunkenness of the husband and mistreatment of his wife, who still addresses him as pyare mian or my dear husband, has been delineated in one of the most expressive satirical drawings. Here, Gaganendranath used colour quite suitably especially for the blood dripping from the wife's forehead. The babus' attitudes, toward women not only represent further comments on the middle class mentality but also imply Gaganendranath's sympathy for women's plight.

Marriage

With an intense social sensitivity, Gaganendranath created a complex satirical drawing on Bengali attitudes and practices concerning marriage. Though the bridegroom may be a romantic dreamer holding the book of Romeo and Juliet, the father is preparing for the funeral of the dead daughter-in-law. The butterfly on her coffin cloth represents 'Prajapati', the mythical priest of wedding rituals. Most telling is the conspicuous imagery of the mother 'fishing' out a little bride from an earthen pot. It is a Bengali practice to feed a sick man with a freshly caught live fish preserved in a water-filled pitcher. The title has been coined quite thoughtfully, Sold Per Force versus Soul Force.

With an intense social sensitivity, Gaganendranath created a complex satirical drawing on Bengali attitudes and practices concerning marriage. Though the bridegroom may be a romantic dreamer holding the book of Romeo and Juliet, the father is preparing for the funeral of the dead daughter-in-law. The butterfly on her coffin cloth represents 'Prajapati', the mythical priest of wedding rituals. Most telling is the conspicuous imagery of the mother 'fishing' out a little bride from an earthen pot. It is a Bengali practice to feed a sick man with a freshly caught live fish preserved in a water-filled pitcher. The title has been coined quite thoughtfully, Sold Per Force versus Soul Force.

The Dance or Ball Room Dance (also called Waltzing Mahila), is available in many versions, especially one with the male figure of dark complexion and a flat nose thereby giving him an Indian identity, is important. He is wearing a coat with tail to refer to his westernization, while his feminine counterpart's dress is a cross between sari and skirt. Their dancing together is an attempt toward harmony that is slated to failure. It is also titled Colour Scream, colour referring to racial prejudice. These caricatures use pictorial allegory and hence are fascinating from an interpretative point of view. depicts the western gown. The woman looks admiringly at her male partner. Gaganendranath has very ably caught the sprightliness, the grace and intimacy of a waltz style of western dancing.

Some feminist commentators see in it the depiction of Bengali women leaving the boundary walls of the home and interacting with the world and men outside. The transformed dress represents the emancipation of the Bengali women, reminding one of the roles of Jnanadanandini Devi, Rabindranath's elder sister-in-law, wife of Satyendranath. She was one of the first women to emerge from the seclusion of the inner apartments. She had felt the inadequacy of the traditional Bengali sari wrapped around the naked body for the purpose of going out. She evolved, along with some other ladies, first a contraption combining a frock with a scarf thrown over the torso and then the Brahmika sari adopted from the Parsi way (Bombay style) of draping on a sari.7

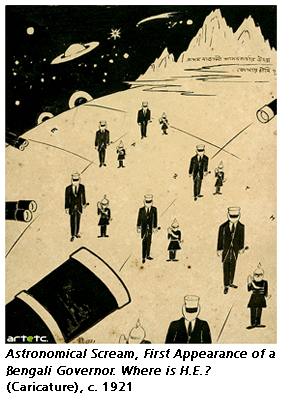

The connecting link among Gaganendranath's satirical drawings was contained in the third and the last volume. Reform Screams, (published in 1921) is the announcement of the Report of the Indian Constitutional Reforms: The Montague-Chelmsford Report. The Report formed the basis of the Government of India Act 1919, which came in to operation early in 1921. The drawings in Reform Screams reveal Gaganendranath as a bold nationalist, which must be acknowledged as a significant pictorial document of that period of the independence struggle. Obviously, Gaganendranath had observed crucial contemporary political events for nearly three years (1919-1921) and gave them expressive form. The reforms of 1919 did not satisfy the national aspirations of our countrymen and their effect upon the national struggle for independence had been like fresh fuel. Mahatma Gandhi was at first inclined to try to make the reforms work, but in a special session held in Calcutta in September 1920, he changed his judgment, and the famous resolution of Non-cooperation was adopted by the Congress party. The object of the National Congress was now defined as the attainment of Swaraj (self-rule) by all legitimate and peaceful means. Swarajya was taken to imply 'self-rule' within the Empire if possible, without if necessary.

Terribly Sympathetic 1921

The vast looming bespectacled man in western dress is a metaphorical image of both the colonial power and the immediate author of a series of new proposals, known as the Montague Chelmsford Reforms. (Sometimes he is identified as Lloyd George). One of the reforms was to announce dominion status as well as to initiate a system of Government in the various Presidency states to be run by elected representatives. Almost simultaneously, with the Reforms of 1919, the colonial Government had passed a set of new coercive measures, known as the Rowlett Act.

State Funeral of H. H. Old Bengal

The immediate casualty after the implementation of the Act of Reforms, 1919, was the disbanding of the existing Legislative Council of Bengal. This occasion was pictorialized by Gaganendranath as a grand western style funeral. That it was a severe jolt to India's journey towards self-rule is definitely the artist's intention. Gaganendranath appropriately turns it into an elaborate narrative episode, not only raising it to the level of serious painting by also reminiscent of his earlier narrative series of Chaitanya Charitamala. While the dead body is not visible, the Indian and British personages (some of whom have been identified) are clearly delineated in distinct mourning dresses.

Satire on lack of or false patriotism

Auto-Speechola or An Automatic Speech Making Machine

In the Birupa Bajra (Strong Thunderbolts) of 1917 he had already targeted zamindars, Maharajas and nominated councilors of Bengal for their lack of conviction and passive intellect. The speeches they delivered in public were prepared for them by others like automatic machines, when writers are merely thoughtless automations conforming to colonial restrictions.

My love of my country is as Big as I am

The cartoon titled My Love of My Country Is as Big as I Am is a satire on false patriotism in which Gaganendranath has depicted himself as the ordinary Bengali listener sitting in the right corner. Wearing simple indigenous dress and smoking the traditional hukka, he is amused to listen to the boastful lecture of the big-bellied figure who dominates the pictorial space. Wearing western dress complete with a cigar held in the left hand, he stands authoritatively, thus an unmistakable satire of the Maharaja Bijaychand of Burdhaman.

Chemical Scream

In the Chemical Scream, the famous chemistry professor, P.C. Roy is trying to wash out patriotism signified by 'Indian ink'. It has an explicit title: Out Damned spot, out I say.8 It is a dig at the Indian scientist's new inventions during the Swadeshi movement, most of which for the purpose of indigenous manufacturing were unsuccessful.

Poetical Scream

Latest Flight of the Poet, Query: Is it cooperation or Non-cooperation? Gaganendranath did not even spare his uncle Rabindranath, when a precise comment had to be made. Seated on his easy chair, and holding an ektara in his right hand, the poet is depicted flying in the sky. His notebooks attached with pen and reading glasses (pince-nez) are scattered in space and he looks bewildered. There are at least two undated drawings in which the sky is dark, in one case filled with stars and crescent moon and in another case, full of white clouds. In the dated drawing of 1921 assuming it to be the final version, the sky is of light tone. An enlarged nib of a pen is turned into a platform on which several inquisitive journalists are perched. The names of the newspapers are written below them such as Young India, The English Man etc.

Latest Flight of the Poet, Query: Is it cooperation or Non-cooperation? Gaganendranath did not even spare his uncle Rabindranath, when a precise comment had to be made. Seated on his easy chair, and holding an ektara in his right hand, the poet is depicted flying in the sky. His notebooks attached with pen and reading glasses (pince-nez) are scattered in space and he looks bewildered. There are at least two undated drawings in which the sky is dark, in one case filled with stars and crescent moon and in another case, full of white clouds. In the dated drawing of 1921 assuming it to be the final version, the sky is of light tone. An enlarged nib of a pen is turned into a platform on which several inquisitive journalists are perched. The names of the newspapers are written below them such as Young India, The English Man etc.

In a witty manner Gaganendranath has juxtaposed two events together so that one signifies the other. It has been recorded that Rabindranath's journey to London on 16 April 1921 was also his first travel by air. Nihal Singh had interviewed the poet and asked him, if that would be his first flight. 'Quick as flash', the poet had replied, that he had been flying all his life, but this would be the first of that sort.9 The other was the ongoing Non-cooperation movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. Naturally everyone was eager to know the poet's opinion on the momentous stage of the independence struggle, but he was air-borne or flying in the sky. The journalists assembled on the pen are looking in various directions to ascertain which side of the earth is his destination this time.

In a witty manner Gaganendranath has juxtaposed two events together so that one signifies the other. It has been recorded that Rabindranath's journey to London on 16 April 1921 was also his first travel by air. Nihal Singh had interviewed the poet and asked him, if that would be his first flight. 'Quick as flash', the poet had replied, that he had been flying all his life, but this would be the first of that sort.9 The other was the ongoing Non-cooperation movement led by Mahatma Gandhi. Naturally everyone was eager to know the poet's opinion on the momentous stage of the independence struggle, but he was air-borne or flying in the sky. The journalists assembled on the pen are looking in various directions to ascertain which side of the earth is his destination this time.

That Rabindranath had disagreed with Mahatma Gandhi has been recorded in the letters exchanged between them.10 Even the personal meeting that Mahatma Gandhi had with him did not elicit his active support. That is why Gaganendranath resorted to an additional phrase in the title of his caricature in the form of a 'query', 'is it cooperation or non-cooperation?' Since this trip was decisive in fundraising to set up the International University at Santiniketan, non-cooperation with Mahatma Gandhi for the 'non-cooperation movement', only underscored cooperation with the British establishment. This 'dithering' on the part of Rabindranath followed soon after his much-hailed decision to return the Knighthood back to the British Crown in response to the Jalianwala Bagh massacre in the Punjab (1919). Gaganendranath had recorded his own agony caused by the political situation in the Punjab in a satirical drawing entitled Peace Reigns in the Punjab which was displayed in an art exhibition in Calcutta inaugurated by Lord Chelmsford.

The notion of 'flight in a dream', when one is hovering aloft the sky and traversing though various lands, derives from Dwinjendranath Tagore's imaginary description in his poem Swapna Prayan, which has been mentioned earlier. The Charkha versus Everything Else (The Modern Review, July 1921) conclusively states the position taken by Rabindranath as well as some other thinkers of the country who held different viewpoints from that of Mahatma Gandhi. Here, Gaganendranath inverts the imagery putting the charkha in the place of the dreamer in the sky, whereas the earthly priorities below are clearly labeled such as: Hospital, Knowledge, Research, Art and so on.

The notion of 'flight in a dream', when one is hovering aloft the sky and traversing though various lands, derives from Dwinjendranath Tagore's imaginary description in his poem Swapna Prayan, which has been mentioned earlier. The Charkha versus Everything Else (The Modern Review, July 1921) conclusively states the position taken by Rabindranath as well as some other thinkers of the country who held different viewpoints from that of Mahatma Gandhi. Here, Gaganendranath inverts the imagery putting the charkha in the place of the dreamer in the sky, whereas the earthly priorities below are clearly labeled such as: Hospital, Knowledge, Research, Art and so on.

Among the extensive satirical drawings of Gaganendranath many of them were finished by him as lithographs. It has been noted that Gaganendranath's cartoons had been printed on the lithography press by a Muslim technician. (i) How did Gaganendranath transfer the drawings on the litho stone? (ii) How were the drawings transformed and adjusted for the lithographic technique to impart to them the aesthetic of graphic art? (iii) What was the role of colour, as many of these are also coloured - lithographs? From the corpus of his drawings, we must distinguish those which were worked out on lithography stone and the kind of devices that are particular to this process of print-making.

Reference

1) Dr. Sukumar Sen, A History of Bengali Literature, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1992.

2) Quoted in Mulk Raj Anand, Gaganendranath Tagore's Realm of the Absurd, JISOA, Birth Centenary Number of Gaganendranath Tagore, Pulin Bihari Sen (ed.), 1972.

3) SIMIPLICISSIMUS, 108 Satirical Drawings from the famous German Weekly, Text by Stanley Appelbaum, New York, 1975.

4) Honore Daumier, 240 Lithographsi, Introductionby Wilhelm Waltmann,Abbey Art Series, London (undated).

5) R.A. Walker, The Best of Beardsley, London (undated).

6) For the description of babu, see NAARI (Magazine), Tilotama Thoru (ed.), Ladies Study Group, Calcutta, 1990.

7) For adaptation of a suitable dress for an emancipated Bengali woman and the role played by Jnanadanandini Devi, see NAARI, ibid.

8) O.C. Gangoly, The Humorous Art o Gaganendranath Tagore, Calcutta, (undated).

9) Sant Nihal Singh, An Evening with Rabindranath Tagore, The Modern Review, July, 1921.

10) Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson(editors/ translators), Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagores, Cambridge University Press,Delhi,1997.