- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

And Quiet Flows the River

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

Profile

by Nalini S Malaviya

The New Delhi based artist, Atul Bhalla has been involved with exploring the physical, historical, spiritual and political significance of water in the urban environment and in local communities through his art installations. In conversation, Nalini S Malaviya takes a closer look.

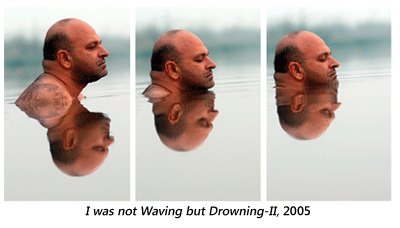

Atul Bhalla has rcently returned from extensive travels that involved a series of presentations at Harvard University, amongst several other places. The talk at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum for instance was held in conjunction with his installation, I Was Not Waving but Drowning II (2005), a work that has been acquired by the Museum. It belongs to a series with the same title which includes 14 digital photographs, based on Stevie Smith's 1957 poem, 'Not Waving but Drowning'.

Atul Bhalla has rcently returned from extensive travels that involved a series of presentations at Harvard University, amongst several other places. The talk at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum for instance was held in conjunction with his installation, I Was Not Waving but Drowning II (2005), a work that has been acquired by the Museum. It belongs to a series with the same title which includes 14 digital photographs, based on Stevie Smith's 1957 poem, 'Not Waving but Drowning'.

As a conceptual artist, Bhalla incorporates photography, video, painting, sculpture and mixed media in his installations. He made a shift from painting to photography and conceptual work in the year 2000. Going through a gestational period that involved a measure of introspection and experimentation with different media, he refrained from showing his works for nearly five years. In 2005, he showed I Was Not Waving but Drowning, a series for which he immersed himself in the Yamuna river, one of the most polluted rivers in the world. Here, the element of 'performance' and photography came together as a viable means of expression. Terming it as 'performative photography', Bhalla realised there were infinite possibilities with the medium, both conceptually and practically, which could be explored over a period of time.

In this work, the photographs portray the artist gradually immersing himself in the Yamuna. The images shown are at the point when his head nears the surface of the water. The reflection in the water makes it appear as though both object and the mirror-image created are joined at the surface. Over the next few images, facial details and their reflections become increasingly blurred until the point that the head completely disappears beneath the surface. In view of the strong religious and spiritual beliefs associated with the river Yamuna, or in fact any other river in India, the loss in clarity is meant to indicate a loss in identity as a direct consequence of environmental pollution.

Over the years, water has become an essential component of Bhalla's art practice. He explains,  “my explorations with water have evolved from personal reasons as well. How water occupies space in our lives as a material and as a substance.” Undoubtedly, the significance of water ranges from deeply personal, political and cultural contexts as a natural element that sustains life, to one that is associated with reverence and spirituality. For Bhalla, visiting Haridwar and Rishikesh was a turning point of sorts, a place where people immerse themselves in the holy river, Ganga and even drink it as a healing agent. Bhalla however also noticed that devotees would opt for bottled water, perhaps reflecting a dichotomy between belief and practice. The visit triggered a philosophical dilemma in the artist's mind as he began questioning the essence of the river water, its significance from both micro and macro perspectives. It also raised questions regarding the altered state of water bodies due to pollution and desecration.

“my explorations with water have evolved from personal reasons as well. How water occupies space in our lives as a material and as a substance.” Undoubtedly, the significance of water ranges from deeply personal, political and cultural contexts as a natural element that sustains life, to one that is associated with reverence and spirituality. For Bhalla, visiting Haridwar and Rishikesh was a turning point of sorts, a place where people immerse themselves in the holy river, Ganga and even drink it as a healing agent. Bhalla however also noticed that devotees would opt for bottled water, perhaps reflecting a dichotomy between belief and practice. The visit triggered a philosophical dilemma in the artist's mind as he began questioning the essence of the river water, its significance from both micro and macro perspectives. It also raised questions regarding the altered state of water bodies due to pollution and desecration.

Close to the artist's home in New Delhi, the river Yamuna runs near the cremation ground and is a receptacle for ashes of the deceased. He says, “the Yamuna is considered to be the sister of Yama, and it is believed that bathing in the river should keep away death, but the river herself is now dying, which is ironic and sad.” Bhalla therefore explores the harmful effects of urbanisation, which is causing pollution of rivers and choking them. On the other hand, deep-rooted beliefs and folk-lore have also been associated with water bodies: this duality arises as rivers are symbols of divinity and not merely physical entities.

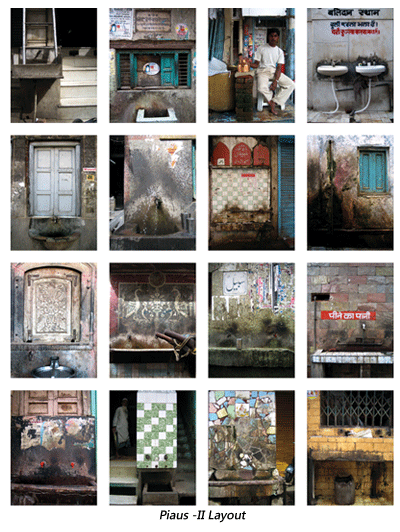

In 2006, Atul Bhalla was a part of Dilli Dur Ast, an Old Delhi based residency organized by KHOJ-International Artists Association, which further opened up possibilities with a lens based medium. As he had already been working on water as a concept, he conceived two works, which he states, “allowed me to further pursue the concept within my own practice and to expand it with an attempt at a different medium.” In order to create one of his works, he learnt how to halal a goat to have a mashk made out of it. Although the idea was to examine the tradition of providing free water from a traditional leather water carrier - mashk, it also examined practices traditionally associated with specific communities. The entire process resulted in a five minute videos and 22 colour prints, while the installation had a mashk and a knife on display. The other work which emerged from the residency involved mapping the 'piaus', the traditional free drinking water sites of Old Delhi and showed in graphic detail how grime and dirt had accumulated all around them.

One notices that Bhalla's 'performative photographs' are not mere snapshots of a moment; there is a much deeper and intrinsic intent that straddles politics, aesthetics, formal and philosophic components creating multiple points of reading and exploring their consequences. Interestingly, the formal and aesthetic content in most of Bhalla's photographs are deceptively sublime and tranquil. Like a beautiful mirage, the serene surface of the water reflects the tangibles even as it conceals the pollutants within its folds.

Bhalla emphasises that in each of his works, his involvement or the 'performance' and the process of creation is a part of the discourse, where the medium is incidental and what takes precedence is the concept through his own journey. This is widely evident in the series entitled 'Yamuna-walk', which traces the artist's five-day walk around a portion of the river that encircles New Delhi, forcing him to climb fences and cross concrete overpasses in his path. Similarly, the 'Mumbai-walk', which mapped all the drains along Marine Drive, from Chaupati to Nariman Point (also a part of the title of the work), expanded his field of reference to another city with a similar problem.

Bhalla explains that the use of diptychs and multiple images is a means to emphasise the message and to allow the viewer to revisit and re-enter the work numerous times. He believes that a subtle and nuanced method of communicating becomes more powerful than having a direct and explicit approach.  Yet, Bhalla is clear that he does not wish his art to become a didactic but rather a catalyst for positive change. He mentions that his practice does not involve “random photography, but a methodical approach.” It invoves studying the site and examinig its cultural and historical nature before responding to it.

Yet, Bhalla is clear that he does not wish his art to become a didactic but rather a catalyst for positive change. He mentions that his practice does not involve “random photography, but a methodical approach.” It invoves studying the site and examinig its cultural and historical nature before responding to it.

Currently, Bhalla is involved with an Indo-German project titled 'Contemporary Flows. Fluid Times'. It examines the interdependency of communities and ecological systems and the sensitive balance that exists between the two – in this case, the river Yamuna in Delhi, and Elbe in Hamburg. The project is jointly curated by Ravi Agarwal and Till Krause and will result in a public art festival – an extension of the recently held seminar that addressed new threats resulting from climate change and “an attempt to rethink of the river as an 'ecology,' using not only science and technology, but also the poetics of our imaginaries.”

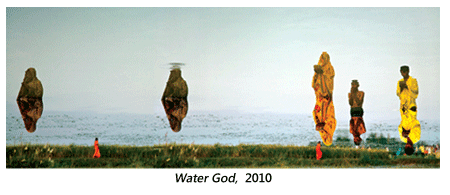

Bhalla reveals that his next series of photographs draw from the illustration of water bodies in mythological legends and tales, such as the Mahabharata, an ancient repository of wisdom and knowledge. He examines the historicity of myths and legends their presence in contemporary life, and the transformations and shifts in our relationships with varied communities.

Images Courtesy: Atul Bhalla