- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Collecting Photography in an International Context

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Nathaniel Gaskell

In order to understand how photography operates on the art market, it is necessary to have a basic comprehension of the medium's history – both in terms of its cultural narrative and its relationship to the art world in general. The invention of photography itself can be seen parallel to the human desire to order, interpret and understand the world around us. The existence of the photography market is therefore a further manifestation of this drive.

interpret and understand the world around us. The existence of the photography market is therefore a further manifestation of this drive.

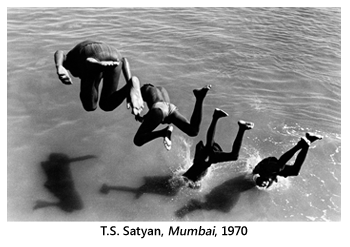

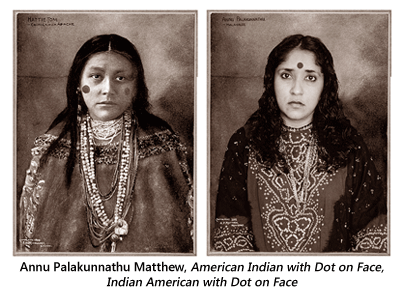

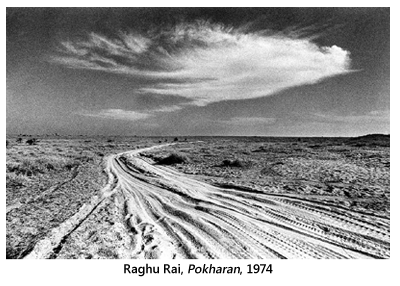

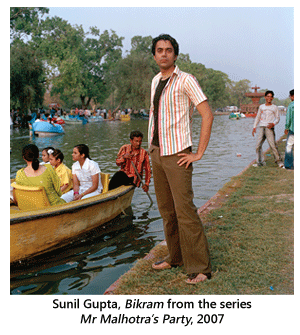

Photography's early history is centered on discoveries in Europe, whereas in the latter half of the 20th Century, a lot of its development and acceptance as an art form took place in America. However, since its inception, photography has had many alternative histories, not least in India. In fact, the early 'travel photography' of the late 19th Century taken in the subcontinent remains an extremely collectable genre, whilst original prints by 20th Century 'masters', such as Raghu Rai, Dayanita Singh and T.S. Satyan, are also highly coveted. Many Indian photographers working today, including Amit Madheshiya, Prabuddha Dasgupta and Mahesh Shantaram, are still following this more documentary tradition, crossing the boundaries between photojournalism and art. Alongside this, photographers such as Annu Palakunnathu Matthew, who uses appropriated images to examine notions of identity, and Sunil Gupta, who explores themes of gender-politics, fit more comfortably into the vein of what can be called Contemporary Art Photography. Having lived in both places, Matthew and Gupta are represented by galleries in India and the West. In fact, a growing number of Indian contemporary artists are gaining recognition on the international art market today and the increased assimilation of photography within these discourses, as well as photography's own position as a unique and distinct medium, will act to secure India's role in the future of contemporary photography, in both art-historical and art-market terms. What follows is an analysis of photography's acceptance into the art world in the West and how this relates to the photography scene in India.

For the idea of collecting photography to really take off in the art world, two main concerns had to be tackled. First, this question regarding photography's justification as art, and, secondly, how it should operate on the market in light of its reproducible nature. Throughout the early 20th Century, whilst many could appreciate the unique aesthetic qualities of photographs, and whilst the pictorialist movement in Europe used photography to mimic the aesthetic criteria of painting, its position in the art world remained ambivalent. There were, however, some early advocates of the medium who were dedicated to promoting it as an art form, and they wrote many articles in its defense. Two such examples are the American gallerist and photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, and the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw. In 1941, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Alfred H Barr, Jr., began collecting photography for the museum with the progressive belief that it was a crucial and valid art form and one that would arguably become the most important visual discipline of the modern world. Soon after, the International Museum of Photography was established at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, and these two institutions paved the way for many more important collections of photography to spring up in the following years. By the 1970s, this established network of museums and galleries gave rise to a whole generation of historians, curators and critics, who all promoted the idea of photography as a unique art. This provided the medium with a much-needed academic and art historical framework and did a lot to increase its legitimacy to the rest of the art world. It was also during the 1970s that the major auction houses in London, Paris and New York began to organize specialist photography sales.

its position in the art world remained ambivalent. There were, however, some early advocates of the medium who were dedicated to promoting it as an art form, and they wrote many articles in its defense. Two such examples are the American gallerist and photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, and the Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw. In 1941, the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Alfred H Barr, Jr., began collecting photography for the museum with the progressive belief that it was a crucial and valid art form and one that would arguably become the most important visual discipline of the modern world. Soon after, the International Museum of Photography was established at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, and these two institutions paved the way for many more important collections of photography to spring up in the following years. By the 1970s, this established network of museums and galleries gave rise to a whole generation of historians, curators and critics, who all promoted the idea of photography as a unique art. This provided the medium with a much-needed academic and art historical framework and did a lot to increase its legitimacy to the rest of the art world. It was also during the 1970s that the major auction houses in London, Paris and New York began to organize specialist photography sales.

In parallel to this, photography's relationship to Conceptual Art practices coming out of America in the 70s, did much to boost its profile. By redefining art as a vehicle for ideas rather than as an object of purely aesthetic or iconographical value, Conceptual Artists championed concept over physicality, and in doing so they undid traditional notions of art's 'objecthood'. Photography featured widely in the work of these artists, largely as a device to document, extend or highlight the processes of their work. Examples would include artists like Gordon Matta Clark, Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer and Martha Rosler. Despite the best efforts of photography's academic advocates, the photograph still had a relatively low profile on the art market in comparison to painting and sculpture, and was considered by many as a cheap, readily available and ephemeral mass-medium. In other words, photography's opposition to traditional notions of the fine art object made its adoption by the Conceptual artists act in synergy with their ideologies regarding object making. Paradoxically, therefore, the inclusion of photography within Conceptual Art's matrix catapulted it into the realm of contemporary art, previously only occupied by painters and sculptors. Despite making work entirely constructed from photographs, artists such as Ed Ruscha, Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, who were working in the 70s with a conceptual bent, were not considered 'photographers' at all, but instead as 'artists using photography'. It was at this point, therefore, that the terminology and categorisation that previously held photography as a separate entity from the rest of the art world had broken down.

It was at this point, therefore, that the terminology and categorisation that previously held photography as a separate entity from the rest of the art world had broken down.

With this bourgeoning place of the photographic image as an object of cultural and market value on the up, be it 19th Century, modern or contemporary, an understanding of the various kinds of prints available and how these should function in regards to exhibitions, collections and the art market in general needed to be laid down. In other words, dealers and auction houses were confronted with the problem posed by a mass-medium from which they had to create notions of rarity, hierarchy and desirability. As such, terms like 'original', 'vintage' and 'edition' were reinvented in the context of photography and their use is now central to how the photography market operates.

Before the advent of digital imaging, any photographic print made from a photographer's original negative was considered as an 'original print'. Some collectors would argue that to qualify as an original, a photograph has to have been printed by the photographer himself, but this argument is redundant for the simple reason that in today's contemporary photography market, and in fact in the world of 19th Century photography too, photographers use assistants to help them realize their ideas in print – the process of conceiving photographic works in many respects being a separate discipline from the craft of printmaking. A more encompassing and correct definition of an original print is therefore one that was made under the supervision of the photographer, or their estate if the print in question in posthumous. The reproducible nature of a photograph means that a photographer can essentially re-print an image at any point throughout their career. The term 'vintage', which in this context is a construct of the photography world, therefore refers to those prints made within about five years of the time the photograph was taken. If a photographer makes a print ten or twenty years later, this is termed a 'later print' and if one is being made considerably later than that, the term 'modern' print is used.

In the absence of a developed market in the first half of the 20th Century, photographers were more casual about the production of their prints. They would not necessarily note the amount of copies they were making and they might even print the same image on different paper, using a different crop, or a different size altogether. This simply doesn't work in today's market. For the photographer to be remunerated for their work, and for the collector to have a framework around which their collection can be valued and traded on the art market, dealers and photographers invented the practice of editioning photographs, largely following  the protocols of print editions in the rest of the art world. By designating the total number prints in an edition of their work, photographers are showing that the prints within that edition are art-objects in their own right, and produced as such in a finite number.

the protocols of print editions in the rest of the art world. By designating the total number prints in an edition of their work, photographers are showing that the prints within that edition are art-objects in their own right, and produced as such in a finite number.

Whilst this system within which fine photographs operate is universal, the history of photography in India ran along slightly different lines. As mentioned, India's dominant contributions to the international photography scene can be split into two categories: 19th Century and contemporary. Internationally, 19th Century photography in India is traded by mainly Western dealers. Taken largely by British photographers such as Samuel Bourne, Charles Shepherd and Francis Frith, but also Indian photographers such as Lala Deen Dayal, these photographs were sold by studios in India as visual records of the Raj. There is an increased interest in this kind of photography in India and in the last few years various exhibitions of the same have been curated, such as the recent Deen Dayal retrospective at the IGNCA in Delhi. 19th Century photographs are also coming back into the country from Europe and sold to the Indian market today. This is creating a kind of photographic repatriation that is perhaps emblematic of the changing world order - both in terms of financial markets in general, but more specifically in regards to photography.

Indian contemporary photography really began to take shape in New Delhi in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with galleries showing photographs as part of their exhibition programmes alongside painting and sculpture. In 1999, for example, Nature Morte exhibited the work of Dayanita Singh in a group show that also included works by Subodh Gupta, Jitish Kallat and Bhupen Khakhar. In 2002 they also exhibited Annu Palakunnathu Matthew's series Bollywood Satirized, which contained photographic re- drawings of film posters and saw the beginning of Matthew's wholesale use of the photograph, as exemplified in her 2003 series 'An India from India'. It is important to note that the inclusion of photography at such exhibitions marked the beginnings of photography's role in the Indian contemporary art market. In a similar way, therefore, to the boost photography received via its association with Conceptual Art in the West in the 70s, the inclusion of photographs in the New Delhi gallery scene at the turn of the last century did much to promote photography as a contemporary art form in India.

With the opening of Tasveer in 2006, photography was championed as the central medium of a gallery's exhibition output, rather than merely fulfilling a supporting role. Subsequently, Tasveer has become the most active institution in the country promoting photography as a singular, yet diverse, art form.  Its role in the future development of the medium in India is therefore fundamental. The outreach of Tasveer is international, and as such it encourages dialogues with the West through its exhibition programming and ties with institutions abroad – a practice not uncommon in the Indian art scene, as shown at the recent Indian Art Summit which included various such collaborations. By exhibiting the work of Western photographers alongside those from India, Indian photography is given a wider context, whilst international shows, such as the recent exhibition of Raghu Rai, Prabuddha Dasgupta and Ryan Lobo at the OFOTO Gallery in Shanghai, or the 2010 exhibition, Where Three Dreams Cross, staged in collaboration with the Whitechapel Gallery in London, are acting to promote Indian photography abroad. As the largest exhibition in Europe of photography from the Indian subcontinent, Where Three Dreams Cross also did a lot to confirm the developing interest and cultural significance of Indian photography, as well as encouraging a reevaluation of the medium's past in an international context.

Its role in the future development of the medium in India is therefore fundamental. The outreach of Tasveer is international, and as such it encourages dialogues with the West through its exhibition programming and ties with institutions abroad – a practice not uncommon in the Indian art scene, as shown at the recent Indian Art Summit which included various such collaborations. By exhibiting the work of Western photographers alongside those from India, Indian photography is given a wider context, whilst international shows, such as the recent exhibition of Raghu Rai, Prabuddha Dasgupta and Ryan Lobo at the OFOTO Gallery in Shanghai, or the 2010 exhibition, Where Three Dreams Cross, staged in collaboration with the Whitechapel Gallery in London, are acting to promote Indian photography abroad. As the largest exhibition in Europe of photography from the Indian subcontinent, Where Three Dreams Cross also did a lot to confirm the developing interest and cultural significance of Indian photography, as well as encouraging a reevaluation of the medium's past in an international context.

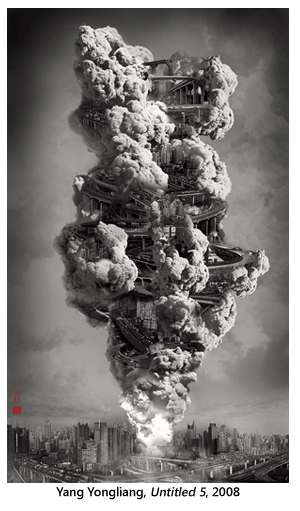

Whilst on the one hand these cross-cultural collaborations are opening up new markets for Indian photographers, they are also acting to develop a market for international photography within India. The success in India of solo shows by European photographers, such as Martine Franck and Karen Knorr, and the forthcoming exhibitions of international photographers, such as the group show of contemporary Chinese photography at Tasveer, which includes work by Yang Yongliang later this year, are just glimpses of how the future market could unfold. Despite the prevailing dominance of Western dealers and collectors, there is a very real, if still nascent, potential for India to play a succinct role in the future of the photography market. More importantly, it will be interesting to see how this change is manifested in the production of contemporary photography itself, as artists and curators respond to the increasingly international art world.

Images Courtesy: Tasveer