- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Sunanda K Sanyal

Back in the 1980s, the photo historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau concluded her insightful essay on art photography with a poignant observation that made many photographers uncomfortable, even irate. Art photography, she wrote, “has systematically engineered its own irrelevance and triviality. It is, in a sense, all dressed up with nowhere to go.”¹ While her comment refers to a major shift in photography's role in the discourse of modern art since the 1960s, the reaction of her critics demonstrates the refusal of many in the photo world to acknowledge the consequences of that shift. Here I want to synopsize the historical transition of photography that serves as the background of Solomon-Godeau's essay, and examine the works of two artists to locate its relevance to contemporary art.

and examine the works of two artists to locate its relevance to contemporary art.

The status of photography in the first half century following its invention was largely unambiguous. Popularly seen as an industrial medium destined to document reality, it had little rivalry with painting. The camera was considered an objective eye without a brain. In an era known for its positivist obsession with empiricism as the basis of all knowledge, faithful emulation of nature was central to the academic discourse of painting. And from such a perspective, it was widely held that the human eye could see much more than the camera, but that unlike human vision, the camera was able to fix slices of reality on a flat surface (this erroneous notion was finally challenged in the 1870s by the English-American photographer Edweard Muybridge's images of human and animal locomotion). It is this ability of the camera to see much more than the human eye and pictorially arrest corporeality that was initially responsible for photography's secondary status in art history; yet later, precisely this same property made it a potent discursive tool in visual culture.

Attempts to treat photography as an art form are indeed evident in the works of the early practitioners of the medium, but it was not until the turn of the 20th Century that a new generation of photographers made concerted efforts to find a niche for it in the emerging discourse of Modernism. The outcome was two-fold. On the one hand, certain Modernist experiments with the nature of representation – namely Cubist collage and Dada photomontage – engaged photography in a critical dialog with Modernist ideas of art. On the other hand, the medium-specific practice of photography spawned two overlapping yet distinct genres: art photography and documentary photography. While aesthetic concern was important for both, it was fundamental to the former, which borrowed much of its formal vocabulary from painting.

With regard to the question of authenticity, a photo is diametrically opposed to a painting. In semiotic terms, it is an icon (due to its resemblance with corporeality) and an index (due to its causal relationship with corporeality). Its unequivocal power of literal reportage and of implying the photographer's presence is what deprived the early photograph of the status of a symbol, which is the key to seeing a photo as a work of art. A painting, in contrast, is artifice through and through, where any indexical value is far superseded by iconic and symbolic ones. The absence of any mechanical process guarantees its one-of-a-kindness; whereas except for daguerreotypes, tintypes and rayograms, a photo is fundamentally a reproducible artifact. However, as painting's claim to originality and transcendence became stronger in the first half of the 20th Century through its increasing denial of its iconic role, photography, too, sought its own legitimacy as art. Modernist aestheticism enabled photographic images to serve as symbols. Impeccable compositional strategies, unusual ambiences, captivating moments etc. were regarded as unique markers of genius. This newfound symbolic role of the photograph succeeded in aestheticizing its iconic and indexical roles by concealing the numerous mediating factors, such as framing, darkroom manipulations and ideological issues, which went into its making. The art photograph thus came to possess an aura that effectively subverted its reproducibility– while it was reproducible as an artifact, it was deemed unique as a creative image. Born was the cult of the print. Even in documentary photography, where iconic and indexical values had an especially crucial role, reportage was offered within a powerful aesthetic framework. In response to its marginal position in the art world, art photography eventually empowered itself through a historiography, connoisseurship, and market of its own. This celebration of the photograph at the expense of photography as a culturally mediated practice would change, beginning in the 1960s, in response to major shifts in the broader discourse of modern art.

Modernism is full of contradictions, which contributes to its complexity. For instance, while the notion of the originality of the work of art and the myth of the individual genius are indeed central to the Modernist discourse,  the Cubist and Dada experiments did much to challenge such assumptions. Not only does the use of mechanized mass culture images fracture the notion of the work of art as a transcendent, unified presence, but it also flaunts the reproducible property of such images in a less-than-auratic manner. In other words, early collage and photomontage powerfully expose the mediating character of photography that art photography toiled so hard to downplay. Therefore, when the unity of the work of art and the supremacy of the author were questioned through such new representational modes as happenings, installations, performances, earthworks and various conceptual practices in postwar art, it ultimately became possible to fully realize the critical potential of photography.²

the Cubist and Dada experiments did much to challenge such assumptions. Not only does the use of mechanized mass culture images fracture the notion of the work of art as a transcendent, unified presence, but it also flaunts the reproducible property of such images in a less-than-auratic manner. In other words, early collage and photomontage powerfully expose the mediating character of photography that art photography toiled so hard to downplay. Therefore, when the unity of the work of art and the supremacy of the author were questioned through such new representational modes as happenings, installations, performances, earthworks and various conceptual practices in postwar art, it ultimately became possible to fully realize the critical potential of photography.²

Whereas a photograph of a conventional work of art is a mere documentation of the piece, photos of art that are by nature fragmented and temporal become inseparable from the work itself, since photographic documentation is an indispensible component of its conceptual framework. For Joseph Beuys' performances, Alan Kaprow's happenings or Christo & Jeanne-Claude's temporary outdoor installations, photography performs its iconic and indexical roles without any aesthetic conceit. As mnemonic devices of an art project that was composed of multiple fragments never intended to crystallize into a permanent product, the photos become party to the open-ended textual process of deconstructing the ontology of art. Thus, they remain symbolic signs of an idea that has long outlasted the actual object or event.

Needless to say, such a self-critical function of photography in the larger discourse of art was incompatible with art photography's medium-specific practice. But since the 1970s, a number of artists who never claimed to be photographers have exploited precisely this conceptual potential of the medium to expose the normativities of a variety of social discourses. One of the earliest such projects is Cindy Sherman's “Film Stills” from 1978.

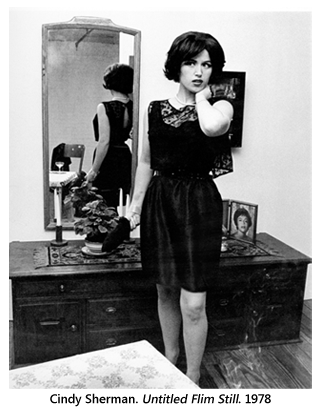

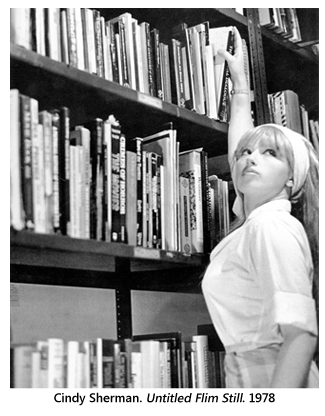

The series consists of seventy-five black-and-white photographs that simulate the look of still images from Hollywood B-movies from the 1940s and the 1950s. With Sherman appropriating a fictive character from a fictive movie, each of them shows a single figure in an outdoor or indoor setting. Each is characteristic of a movie still in its composition, immediacy, light and texture, showing a fragment of a larger narrative arrested in a snapshot, like a disjunctive utterance of a specifically unknown yet culturally familiar speech. Taken as a whole, the hybridity of the entire series signifying myriad nonexistent movies, resists any completion of that speech. The project raises intriguing questions about social as well as representational issues.

As representations of stereotypical female roles from movies of a bygone era, the images speak of the gender discourse of a capitalist society where docility of women was the norm. Each “character”  seems helplessly trapped in its environment. Her apprehensive glance outside the frame turns an apparently benign setting like a library or a living-room into an intimidating, claustrophobic space, where she appears vulnerable to some unseen threat. And buried in this array of “fake” portraits is the provocative question of the artist's self-representation. Sherman's role-playing in this series demonstrates a powerful play between the notion of personality (something innate and essential) and persona (something tentative and multi-dimensional). In the shadows of the cinematic females, with which she had grown up to be a woman, are these Sherman's self-portraits? Does she, in the process of deconstructing these imagined roles that perform according to accepted social codes, also delve into her own gender identity? Furthermore, as both the subject and object of her images, does she succeed in displacing her authorial role?

seems helplessly trapped in its environment. Her apprehensive glance outside the frame turns an apparently benign setting like a library or a living-room into an intimidating, claustrophobic space, where she appears vulnerable to some unseen threat. And buried in this array of “fake” portraits is the provocative question of the artist's self-representation. Sherman's role-playing in this series demonstrates a powerful play between the notion of personality (something innate and essential) and persona (something tentative and multi-dimensional). In the shadows of the cinematic females, with which she had grown up to be a woman, are these Sherman's self-portraits? Does she, in the process of deconstructing these imagined roles that perform according to accepted social codes, also delve into her own gender identity? Furthermore, as both the subject and object of her images, does she succeed in displacing her authorial role?

Even though Sherman's photographs defy the aesthetic obsession of art photography, they emerge as vibrant symbols, where the photo as an artifact is subservient to photography as a mediating agent. If female roles in movies are simulations, then Sherman's staged images of imagined movie characters are meta-images; they are perfect instances of what Jean Baudrillard calls the simulacrum of the third order. Rejecting the real, yet generating their own sense of reality, they are hyperreal signs par excellence. Since the photos document only constructed scenarios (which is what actual movie stills do as well), their iconic and indexical values are categorically subverted by their role as symbolic signs. Attention to such artifice as the reflection of a glass of wine on a table and a jacket hanging from a chair, or the titles of the books on the library shelf heightens the drama of each scene and intensifies the symbolism of the image. And as symbols, the photos signify the discursive role of photography as a representational mode, no less than they allude to the legacy of gender discourse in American society.

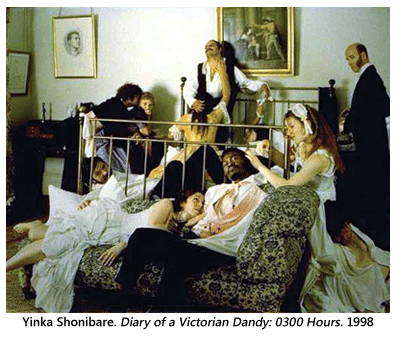

There is no question that projects like Cindy Sherman's “Film Stills” significantly inform the Nigerian-British artist Yinka Shonibare's 1998 series “Diary of a Victorian Dandy”. A set of large color prints in Victorian frames “documents” the daily schedule of a dandy, played by Shonibare himself. Using appropriate settings and a cast of characters, each staged scene meticulously reconstructs the dizzyingly laid-back lifestyle of this Victorian narcissist, surrounded by lackeys – an indispensible component of dandyism – through all hours of day and night. He plays billiard with his shameless toadies at five in the evening, and engages in an open orgy with them at three in the morning. The centrality of an imagined character who is more a social type than a specific individual recalls Sherman's work. However, where Shonibare's project strikingly differs from Sherman's is in his insertion of himself as a dandy without hiding his racial identity.

Dandyism represents a subculture within a colonial society. A dandy was a middle-class young man who so aspired to aristocracy that he rigorously constructed for himself an identity of an eligible socialite. With a persona normalized by Victorian society as a personality, the dandy, then, is a sign of colonial decadence. A black man as a Victorian dandy would be an impossibility, yet that is exactly what seems to happen in the photo series. The son of a Nigerian father and a white English mother, Shonibare is a product of an uneven cross-cultural dynamic, rooted in the colonial discourse of otherness; racial, ethnic and other identity questions have always been a crucial aspect of his life in British society. In response, here he playfully yet aggressively substitutes a postcolonial sign for a colonial one. The stereotypical image of his bi-racial self, however, is a far more multivalent sign than the one it displaces. Shonibare deconstructs the notion of authenticity with regard to identity more forcefully than Sherman. The odd resonance of a black male as a Victorian socialite surrounded by white yes-men uses photography as its active accomplice to wittily imply identity as a social construct. Not only is the artifice of the photographed scenes obvious, but so is the anachronism of the large colour prints in elaborate Victorian frames. Most importantly, it exposes history itself as a construct.

Painting is no longer central to our visual culture. Having lost the codes that once made painted images intelligible across a broad audience, it is now a specialised medium meant for the initiated few. On the other hand, the ubiquity of the photographic image in the over-saturated visual culture of today, cannot be overstated Along with the moving image, it has taken over the public role of painting. What is more, if Modernist art photography once forcefully legitimised the camera, the digital image as a powerful simulacrum has completely undermined it. It would then seem logical to assume that in an age notorious for its manipulation of images, the old faith in the iconic-indexical role of the photograph – its ability to present facts through resemblance – would be a relic of the past. But in fact, the notion of “truth” associated with it still has its firm grip on society. Not only does the photograph remain a reliable arbiter in myriad contexts, from official identification to criminal investigation, but it continues to play a vital role in the art scene as well. As the immense controversy surrounding Andres Serrano's “Piss Christ” and Robert Mapplethorpe's “Portfolio X” in the late 1980s demonstrates, the symbolic function of a photo can still be hijacked by its innate capacity as an icon and an index.

Photography as a discipline has had to evolve radically to come to terms with such complexity of the role of the photographic image in contemporary visual culture. Despite being thoroughly commoditised and conceptually exhausted, the cult of the print still exists as a retrograde, but a lucrative enterprise with noticeable influence on a substantial following. In fact, there is a market-friendly effort in that milieu to co-opt the aesthetic language of Modernist art photography for the digital image. In more critical circles however, ambitious experiments by the younger generations have pushed the boundaries of the older definitions and norms of art photography. For instance, as more and more photographers critically reinterpret the conventional notion of photo reportage while keeping themselves open to everything from large format cameras to Photoshop and from outdoor shoots to studio constructs, the Modernist distinction between art and documentary photography is significantly blurred. Yet others now explore the ontology of the medium itself. “Working everywhere from Photoshop to woodshop”, writes one critic about certain young artists, “a growing number of photographers shoot, appropriate, manipulate, print, paint, and sculpt their works, making objects that stretch the traditional definition of the medium.” Finally, many artists who do not primarily identify themselves as photographers, rely heavily on photographic images as a vital component of their work.

photographic image in contemporary visual culture. Despite being thoroughly commoditised and conceptually exhausted, the cult of the print still exists as a retrograde, but a lucrative enterprise with noticeable influence on a substantial following. In fact, there is a market-friendly effort in that milieu to co-opt the aesthetic language of Modernist art photography for the digital image. In more critical circles however, ambitious experiments by the younger generations have pushed the boundaries of the older definitions and norms of art photography. For instance, as more and more photographers critically reinterpret the conventional notion of photo reportage while keeping themselves open to everything from large format cameras to Photoshop and from outdoor shoots to studio constructs, the Modernist distinction between art and documentary photography is significantly blurred. Yet others now explore the ontology of the medium itself. “Working everywhere from Photoshop to woodshop”, writes one critic about certain young artists, “a growing number of photographers shoot, appropriate, manipulate, print, paint, and sculpt their works, making objects that stretch the traditional definition of the medium.” Finally, many artists who do not primarily identify themselves as photographers, rely heavily on photographic images as a vital component of their work.

No serious artist or critic today would argue against photography's status as art. More crucially, however, with the total exhaustion of such medium-specific debates in art criticism, the question itself is largely irrelevant in the face of the hybridity of contemporary art. And projects like “Film Stills” and “Diary of a Victorian Dandy” play an instrumental role in making such questions obsolete by recognising the powerful discursive potential of photography, rather than the fetishistic role of the photograph.

The author is Associate Professor of Art History and Critical Studies at the Art Institute of Boston at Lesley University.

¹Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “Photography after Art Photography”. In Brian Wallis ed. Art after Modernism: Rethinking Representation. New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art & Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc., 1984: 85.

²For reference to the role of photographs in earthworks, see Sanyal, Sunanda K. “Installation in Perspective: Two Outdoor Projects”. Art News & Views, 3(8), April 2011.

Photos Courtesy: the Author