- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Sabeena Gadihoke

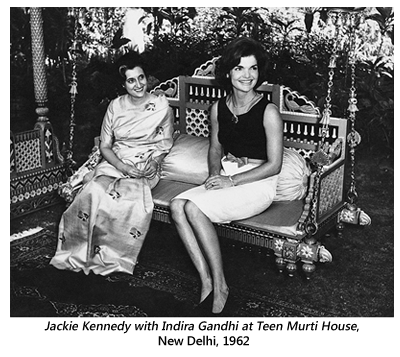

In 1962, Jackie Kennedy was a state guest of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in India. Pictures of the American President's glamorous partner were in great demand from prominent magazines in Delhi. On the first day of her stay at Teen Murti House, a press photographer went to check on why she was taking so long to come out for the photo session. Looking through the window and seeing Mrs. Kennedy clad in a black and white skirt and sleeveless top, he returned to complain to a colleague, “She is not even dressed appropriately as yet!” The colleague he was speaking to happened to be the only woman among press photographers in Delhi at the time. She came from a cosmopolitan community, the Zoroastrian Parsi faith where women did not face too many restrictions around their attire. Despite her background and the nature of her profession, this press photographer insisted on wearing a saree. For years, weighed down by several cameras, she even rode a bicycle to work.

In 1962, Jackie Kennedy was a state guest of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in India. Pictures of the American President's glamorous partner were in great demand from prominent magazines in Delhi. On the first day of her stay at Teen Murti House, a press photographer went to check on why she was taking so long to come out for the photo session. Looking through the window and seeing Mrs. Kennedy clad in a black and white skirt and sleeveless top, he returned to complain to a colleague, “She is not even dressed appropriately as yet!” The colleague he was speaking to happened to be the only woman among press photographers in Delhi at the time. She came from a cosmopolitan community, the Zoroastrian Parsi faith where women did not face too many restrictions around their attire. Despite her background and the nature of her profession, this press photographer insisted on wearing a saree. For years, weighed down by several cameras, she even rode a bicycle to work.

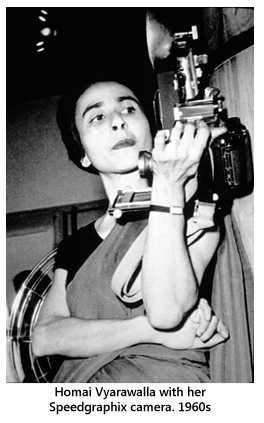

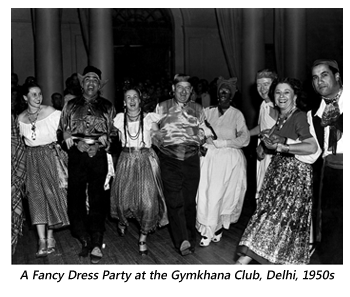

Creator of a rich archive of historical images, India's first woman press photographer, Homai Vyarawalla photographed for over three decades, from the late 1930s to 1970. This was an extremely significant period in Indian history that spanned the birth of the nation and the two decades after, marking euphoria and disillusionment with undelivered promises from the 1960s. Her heterogeneous body of work during this time straddled different historical and cultural spaces.  Homai Vyarawalla worked for the British High Commission and not surprisingly a significant part of her repertoire focused on capturing official events in the capital. Her employers did not discourage her from following her own independent subjects and Homai soon became a familiar figure at social and cultural gatherings in the city. She was the 'preferred' photographer at the St James Church in Kashmiri Gate and her photographs of these “high society” weddings were published in the Onlooker magazine. Mr. Kapur, the dynamic principal of Modern school requested Homai to cover his school functions. She also had an unrestricted entry to the Delhi Gymkhana Club where she photographed fancy dress parties and dances. Exploring the city by foot, Homai captured street life and the monuments of old Delhi. All this and more makes Homai Vyarawalla one of the key chroniclers of the Nehruvian era. And then, having been a professional working woman for thirty-three years, she slipped with absolute ease one day into a life of a homemaker, never looking back once on her career.

Homai Vyarawalla worked for the British High Commission and not surprisingly a significant part of her repertoire focused on capturing official events in the capital. Her employers did not discourage her from following her own independent subjects and Homai soon became a familiar figure at social and cultural gatherings in the city. She was the 'preferred' photographer at the St James Church in Kashmiri Gate and her photographs of these “high society” weddings were published in the Onlooker magazine. Mr. Kapur, the dynamic principal of Modern school requested Homai to cover his school functions. She also had an unrestricted entry to the Delhi Gymkhana Club where she photographed fancy dress parties and dances. Exploring the city by foot, Homai captured street life and the monuments of old Delhi. All this and more makes Homai Vyarawalla one of the key chroniclers of the Nehruvian era. And then, having been a professional working woman for thirty-three years, she slipped with absolute ease one day into a life of a homemaker, never looking back once on her career.

Early Years

Born in 1913, Homai's father was an actor in an Urdu-Parsi theatre company. Growing up in the city of Bombay, it was here that she eventually met her future husband, Maneckshaw Vyarawalla who was a self-taught photographer. She got her first lessons on using the camera from him but given the difficulty of a woman being accepted as a professional photographer in those days, Homai's own images were first printed under Maneckshaw's name and credited with his initials, “M J V”. Homai's early photographs in the thirties' and forties' are a visual record of every-day urban life in Bombay. While most of them depicted a developmentalist colonial state through themes of scientific and social transformation they also reflected other stories of everyday life. Homai captured several of her women friends at the J J School of Arts, as they learnt career skills and participated in utility services for the Second World War. Her earliest pictures feature these young women at picnics where they pose for the camera like film stars. This part of her work has perhaps received less attention in retrospect. Homai's eventual move to Delhi directed her photography away from these subjects towards nationalist politics. The end of the War in 1945 marked a major shift in her work from an emphasis on civilian life to covering high profile events and elite nationalist icons in the capital.

She got her first lessons on using the camera from him but given the difficulty of a woman being accepted as a professional photographer in those days, Homai's own images were first printed under Maneckshaw's name and credited with his initials, “M J V”. Homai's early photographs in the thirties' and forties' are a visual record of every-day urban life in Bombay. While most of them depicted a developmentalist colonial state through themes of scientific and social transformation they also reflected other stories of everyday life. Homai captured several of her women friends at the J J School of Arts, as they learnt career skills and participated in utility services for the Second World War. Her earliest pictures feature these young women at picnics where they pose for the camera like film stars. This part of her work has perhaps received less attention in retrospect. Homai's eventual move to Delhi directed her photography away from these subjects towards nationalist politics. The end of the War in 1945 marked a major shift in her work from an emphasis on civilian life to covering high profile events and elite nationalist icons in the capital.

Independent India and Press Photography

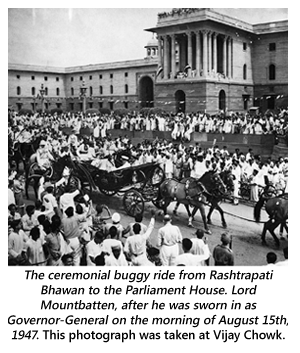

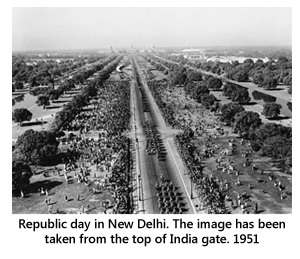

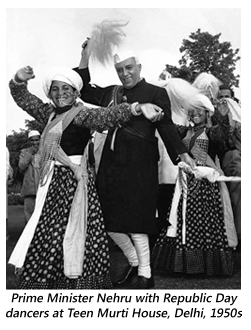

India became independent on August 15 1947 and obviously one lot of photographers did not set aside their cameras to give way to another when the clock struck 12. Instead what we have is a trajectory of continuity and very gradual change. If imperial durbars and hunts were important subjects for photographers in colonial India, they had post colonial equivalents in State performed ceremonial functions and rituals like Republic Day. In post independence India, these spectacles of iconic events could be captured using more mobile and instantaneous technologies. Homai Vyarawalla recalls being able to climb to the top of India gate in order to get a bird's eye view of Rajpath during Republic Day. Of course there were still some limitations that press photographers faced. The high costs of photographic supplies and equipment meant that user friendly technologies arrived with a time lag in India.

India became independent on August 15 1947 and obviously one lot of photographers did not set aside their cameras to give way to another when the clock struck 12. Instead what we have is a trajectory of continuity and very gradual change. If imperial durbars and hunts were important subjects for photographers in colonial India, they had post colonial equivalents in State performed ceremonial functions and rituals like Republic Day. In post independence India, these spectacles of iconic events could be captured using more mobile and instantaneous technologies. Homai Vyarawalla recalls being able to climb to the top of India gate in order to get a bird's eye view of Rajpath during Republic Day. Of course there were still some limitations that press photographers faced. The high costs of photographic supplies and equipment meant that user friendly technologies arrived with a time lag in India.  The 35 mm Leica that used roll film had arrived by the 1930s but it only became popular in India in the 1960s. This had a decisive influence on press photography. Medium format cameras such as the Speedgraphix and Rolleiflex may have been relatively more mobile but these cameras with their big flashbulbs were still bulky. They used plate films that could only give eight or twelve exposures at a time after which the plate needed to be replaced. Moreover it was difficult to assess the final image in many of these twin-lens reflex cameras. Given the high costs of equipment, many photographers could not afford accessories like flash guns or tele-photo lenses. Some of these ground realities put limits on the instantaneity of the press photograph as photographers needed to

The 35 mm Leica that used roll film had arrived by the 1930s but it only became popular in India in the 1960s. This had a decisive influence on press photography. Medium format cameras such as the Speedgraphix and Rolleiflex may have been relatively more mobile but these cameras with their big flashbulbs were still bulky. They used plate films that could only give eight or twelve exposures at a time after which the plate needed to be replaced. Moreover it was difficult to assess the final image in many of these twin-lens reflex cameras. Given the high costs of equipment, many photographers could not afford accessories like flash guns or tele-photo lenses. Some of these ground realities put limits on the instantaneity of the press photograph as photographers needed to  work by instinct and be more measured while shooting.

work by instinct and be more measured while shooting.

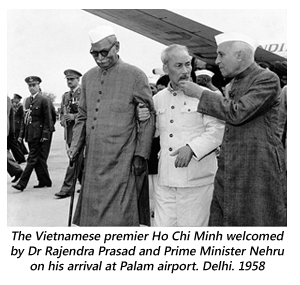

The process of decolonisation and the early years of nation building in India were imbued with euphoria and hope. Most press photographers who were also citizen-subjects were not unaffected by this optimism that found expression in their images of spectacular national events. Despite being predicated on candid photography (this was the era of the 'decisive moment') I suggest that their iconography actually took some of its representational cues from an earlier more staged sensibility with associated notions of propriety. The bodies of 'Leaders' for instance could not be photographed in 'disarray.' This was also a consequence of the fact that press photographers were directly  or indirectly dependent on State patronage for their images of contemporary politics. Among the many images of Nehru in Homai Vyarawalla's collection is a photograph of President Rajendra Prasad and the Prime Minister receiving the premier of North Vietnam Ho Chi Minh on his visit to India. Homai did not exhibit this photograph publicly till very recently. Taken spontaneously as they chatted, the image captures Nehru gesticulating with his hand. However the formation of their bodies in motion caught by the camera makes it seem like the Prime Minister was pulling Ho Chi Minh's beard! Vyarawalla took pride in her candid photography but at the same time she was also emphatic about not compromising the dignity of her important subjects. In visual terms this meant imbuing the image with what she termed 'grace'.

or indirectly dependent on State patronage for their images of contemporary politics. Among the many images of Nehru in Homai Vyarawalla's collection is a photograph of President Rajendra Prasad and the Prime Minister receiving the premier of North Vietnam Ho Chi Minh on his visit to India. Homai did not exhibit this photograph publicly till very recently. Taken spontaneously as they chatted, the image captures Nehru gesticulating with his hand. However the formation of their bodies in motion caught by the camera makes it seem like the Prime Minister was pulling Ho Chi Minh's beard! Vyarawalla took pride in her candid photography but at the same time she was also emphatic about not compromising the dignity of her important subjects. In visual terms this meant imbuing the image with what she termed 'grace'.  In another interview Vyarawalla is critical of a famous Cartier Bresson photograph that features Nehru making a face as he stands between Lord and Lady Mountbatten. After all”, she asserts, “you cannot make our Prime Minister look like a clown!” While the photographer's interviews reveal her strong sense of ethics around the shooting of her subjects, they also indicate the aura and reverence attached to the bodies of public figures.

In another interview Vyarawalla is critical of a famous Cartier Bresson photograph that features Nehru making a face as he stands between Lord and Lady Mountbatten. After all”, she asserts, “you cannot make our Prime Minister look like a clown!” While the photographer's interviews reveal her strong sense of ethics around the shooting of her subjects, they also indicate the aura and reverence attached to the bodies of public figures.

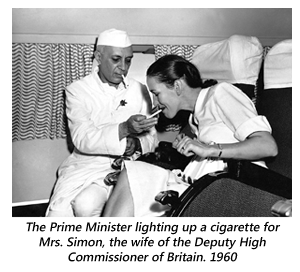

The lack of security requirements in early post independence India assured the close proximity of photographers to charismatic leaders like Gandhi and Nehru. While most events of this time isolated the leader from the 'crowd', the iconicity of these politicians was also heightened by the use of flash bulbs during the day and the low angles prompted by the use of the medium format camera. Despite being one of the most photographed men in history, Mahatma Gandhi actually hated the flash. Nehru on the other hand is remembered as “the darling of the photographers”. Extremely camera friendly, he was not averse to performing for them in both public and private moments.

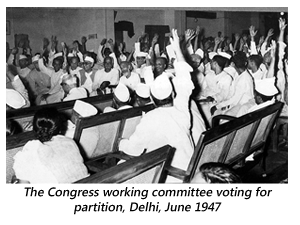

In documenting key events and personalities of this time, press photographers, often unconsciously became visual archivists of the official history of the nation. The unfurling of the flag at Red Fort on Independence Day had such a powerful presence in popular imagination that even the memory around it was framed in accordance. At exhibitions, Homai Vyarawalla has always had to explain that the first such event was actually on August 16th, 1947 and not August 15th the officially recognized date of Independence. While most of her images of the early years of the nation were predictably 'euphoric' they acquire a certain irony when viewed through the prism of historical events over the last sixty years. For instance, in a photograph of the first cabinet lunching at Patel's house in 1950 are both the Dalit leader, Dr Ambedkar and Shyama Prasad Mookerji who later founded the Right wing Jan Sangh . It is also interesting to see what we chose to forget.

Among Homai's collection are several images of an important Congress meeting held two months before independence in New Delhi, where leaders including Nehru, are seen raising their hands, albeit halfheartedly. This was a meeting where the June 3rd plan or the decision to partition the country was ratified by the Congress Working Committee. Never becoming part of our collective memory of Partition, Homai's narrative about this meeting reveals critical insights into the history that she was witnessing. “I felt absolutely disappointed about partition. They were in a hurry to take power into their own hands and if you see my pictures of the final meeting, where they said 'raise hands for partition' you could see that there were very few people there.  India is so big: they should have taken the consensus of people but they didn't do that”.

India is so big: they should have taken the consensus of people but they didn't do that”.

While her days were spent photographing political events, Homai had a completely different agenda at night. This was when she replaced her cotton sari for a silk one and set out for the Gymkhana Club or an Embassy party where she covered the social life of Delhi. Her images of fancy dress parties, fashion shows, boisterous games and sporting events represent a glimpse into a small but elite sub-culture of the city. The Gymkhana Club had opened its doors to Indians only after Independence and while the colour of its guests may have changed, its functions and membership remained as embedded in social hierarchy as before. However the colonial encounter was more complex and Homai's friendships with numerous Europeans are also representative of other kinds of collaborations. Her images pay homage to this encounter.

Retirement and Rediscovery

After a self-imposed retirement in 1970, Homai Vyarawalla settled into a life of anonymity in Pilani where she was homemaker for her only child, Farouq. Her previous life was never invoked till a chance newspaper interview 'outed' her as a photographer. She would subsequently re-visit her professional career as article after article asked her to recollect the past. Perhaps it was in this act of remembrance that the Nehruvian era came to be represented as a time of 'innocence'. While her images of a white-washed Connaught Place might seem symbolic of this nostalgia, Homai's oral narratives about those times are often far more complex. One such example is a description of what happened in Connaught Place during Partition. Homai's landlords in the locality were a Muslim family who fled to the camps leaving their home under the protection of their Parsi tenants. Despite best efforts to guard the house, a Hindu family who had migrated from Pakistan forcibly occupied the shop. A prominent and respected family of Delhi today, Maneckshaw witnessed them forcing one of the sons of their landlord to sign away their property at the point of a dagger. She never saw them again. Nehru may have been her favourite subject but Homai thought that he surrounded himself with a coterie and could not see the corruption infiltrating Congress politics. Despite her photographs of backlit leaders, development projects and uncluttered streets, Homai's disappointment with the Nehruvian dream was evident in her interviews that followed. The same breakdown of “values” in her profession was to push her to lay down her camera in 1970 and never pick it up again.

professional career as article after article asked her to recollect the past. Perhaps it was in this act of remembrance that the Nehruvian era came to be represented as a time of 'innocence'. While her images of a white-washed Connaught Place might seem symbolic of this nostalgia, Homai's oral narratives about those times are often far more complex. One such example is a description of what happened in Connaught Place during Partition. Homai's landlords in the locality were a Muslim family who fled to the camps leaving their home under the protection of their Parsi tenants. Despite best efforts to guard the house, a Hindu family who had migrated from Pakistan forcibly occupied the shop. A prominent and respected family of Delhi today, Maneckshaw witnessed them forcing one of the sons of their landlord to sign away their property at the point of a dagger. She never saw them again. Nehru may have been her favourite subject but Homai thought that he surrounded himself with a coterie and could not see the corruption infiltrating Congress politics. Despite her photographs of backlit leaders, development projects and uncluttered streets, Homai's disappointment with the Nehruvian dream was evident in her interviews that followed. The same breakdown of “values” in her profession was to push her to lay down her camera in 1970 and never pick it up again.

The Lady in the Rough Crowd

Once, Homai Vyarawalla was asked by Dr. Ambedkar, “How did you get into this rough crowd?” The only professional woman press photographer in her time, Homai had an extremely cordial and comfortable relationship with her male colleagues. Her acceptance by others was the result of a careful juggling of codes of behavior.  It is interesting that her colleagues referred to her as “Mummy”. She shrewdly notes how this became a mode of address that she used to her advantage. An extremely attractive woman, Homai cultivated a persona that kept people at a distance. Perhaps in this lay the key to her successful working relationship as the only woman photographer among the men at that time. Her Parsi background may have helped and the easy acceptance of a woman as a photojournalist is also due in large measure to the support of many British employers with whom Homai developed deep friendships. As a pioneering woman in her time, Homai Vyarawalla straddled several identities and spaces. Her vast body of work offers a rich and multi layered photographic archive of the Nehruvian era that we are yet to fully access.

It is interesting that her colleagues referred to her as “Mummy”. She shrewdly notes how this became a mode of address that she used to her advantage. An extremely attractive woman, Homai cultivated a persona that kept people at a distance. Perhaps in this lay the key to her successful working relationship as the only woman photographer among the men at that time. Her Parsi background may have helped and the easy acceptance of a woman as a photojournalist is also due in large measure to the support of many British employers with whom Homai developed deep friendships. As a pioneering woman in her time, Homai Vyarawalla straddled several identities and spaces. Her vast body of work offers a rich and multi layered photographic archive of the Nehruvian era that we are yet to fully access.

The Homai Vyarawalla collection is on permanent loan to the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi, that is dedicated to researching the archives and providing a public platform. Over the last year, a retrospective exhibition of Homai has been organised by the Alkazi Foundation and the National Gallery of Modern Art, curated by Sabeena Gadihoke in Delhi and Mumbai. It opens in the Bangalore NGMA on May 8, 2011 and will be on view for 2 months.

Sabeena Gadihoke is Associate Professor at the AJK MCRC, Jamia University. Her biography "Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla" was published by Mapin/Parzor in 2006. Versions of this article have appeared in Indian Horizons, ICCR, Vol 54, No 4, Oct-Dec 2007 and India Perspectives, Ministry of External Affairs, Vol 22, No 3, June-July 2008

Images Courtesy: H.V. Archive/The Alkazi Collection of Photography