- Prelude

- Editorial

- Raghu Rai: The Historian

- Ryan Lobo, 34 in Baghdad

- Through the Eye of a Lensman

- Adrian Fisk

- And Quiet Flows the River

- The Lady in the Rough Crowd: Archiving India with Homai Vyarawalla

- Raja Deen Dayal:: Glimpses into his Life and Work

- Raja Deen Dayal (1844-1905) Background

- Vintage Views of India by Bourne & Shepherd

- The Outsiders

- Kenduli Baul Mela, 2008

- Collecting Photography in an International Context

- Critical Perspectives on Photograph(y)

- The Alkazi Collection of Photography: Archiving and Exhibiting Visual Histories

- Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

- Kodachrome: A Photography Icon

- Three Dreams or Three Nations? 150 Years of Photography in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Show And Tell – Exploring Contemporary Photographic Practice through PIX

- Vintage Cameras

- Photo Synthesis

- The Right Way to Invest

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata: March – April 2011

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- North East Opsis

- Previews

- In the News

- Somnath Hore

ART news & views

Looking Back at Tasveer's Fifth Season

Volume: 3 Issue No: 16 Month: 5 Year: 2011

by Nathaniel Gaskell

After years of living in the shadow of India's thriving contemporary art scene, photography is finally getting the recognition it deserves. Many of the country's leading art galleries include lens based media as part of their exhibition programmes and a variety of spaces dedicated solely to championing photography as an art form, such as Photoink, Tasveer and the Matthieu Foss Gallery, have popped up in the last 10 years. The recent exhibition, Contemporary Photography form the V&A at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bangalore also suggests that the larger public institutions are acknowledging the cultural importance of photography. In addition to this, a solid infrastructure is  developing between galleries and educational institutions, ensuring that photographic talent in the country is receiving vital grass roots support. As such, The National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad now offers a Masters in Photographic Design and the Srishti School of Art and Design in Bangalore provides a specialisation in Gallery Practice in the context of photographic arts. In 2008, Toto Funds the Arts established an award for promising photographers and this is also playing a crucial part in supporting new ideas and emerging talent.

developing between galleries and educational institutions, ensuring that photographic talent in the country is receiving vital grass roots support. As such, The National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad now offers a Masters in Photographic Design and the Srishti School of Art and Design in Bangalore provides a specialisation in Gallery Practice in the context of photographic arts. In 2008, Toto Funds the Arts established an award for promising photographers and this is also playing a crucial part in supporting new ideas and emerging talent.

Tasveer is involved in a number of different ways in endorsing these various initiatives. As well as tying up with institutions within India, the gallery also collaborates with dealers and organisations internationally. By looking at the past six shows that Tasveer has staged, we can see how these cross-cultural dialogues become manifest in the exhibition programming, and sometimes in the work itself.

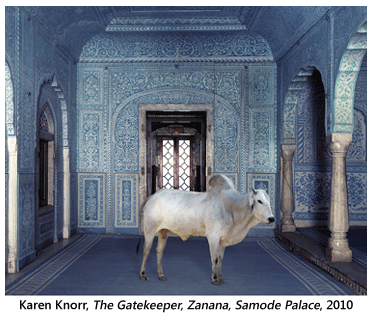

Karen Knorr - Transmigrations

UK photographer Karen Knorr began collaborating with Tasveer in 2008 to produce her ongoing body of work, India Song. By opening up many of the palaces in which the work was made, the gallery played an integral part in the production of the series. In the photographs, exotic animals occupy the interiors of stately buildings, from which they are normally forbidden. Each creature is symbolic and its placement within the opulent architectural space is loaded with possible readings. Since the 1970s, Knorr's work has lent itself to feminist critique and associated theories regarding the 'politics of representation'. In her India Song work, this is expressed in the relationship between feminine subjectivity and animality in Rajput architectural zones, where she considers men's space (mardana) and women's space (zanana) in palaces, havelis and mausoleums. The animals and the informative titles of the photographs, such as The Gatekeeper, Zanana and Samode Palace, simultaneously refer to specific avatars of feminine historic characters whilst also appealing to our imaginations as celebrations of the universal and inherent mythical properties of animals. There is, however, something so seductively pleasing about Knorr's work on purely aesthetic terms that this synergy with art theory recedes to the periphery as we relish in her finesse as an image-maker. Our eyes indulge in the visual display and we get lost in the exquisitely sharp details of the photographs - a result of Knorr combining a large format film camera with the latest digital technology.

100 Vintage Views of India

100 Vintage Views of India presented some of the earliest photographs ever taken in the country, and showed many of India's most recognizable monuments. These images were taken in the medium's infancy and they therefore constitute some of the very first photographs of the subjects they depict, by some of the most well known early photographers: Samuel Bourne, Francis Frith and Edward Sache, to name a few. Many of these photographs exist only in low numbers and the idea for the exhibition was therefore to provide an opportunity to see such important historical items en masse.

Emerging from the spirit of Victorian enlightenment, the invention of photography coincided with the European age of colonization and exploration. The 'travel photography' of the early 19th Century can be seen as a technological manifestation of the Victorian desire to categorize and order the world in an attempt to control and understand what was to them 'Other' or exotic. Making an interesting comparison with the architecture in Knorr's work, the photographs on display also touched upon the inherent dichotomy within all photographic images: their intellectual and conceptual framework on the one hand, and their more experiential and aesthetic qualities on the other.

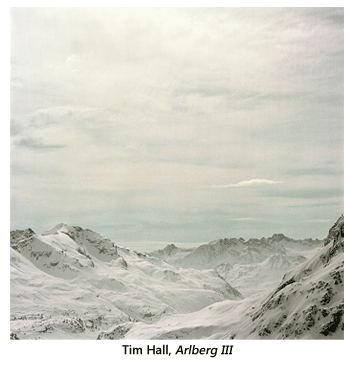

Tim Hall – Escape

Whereas many of Tasveer's exhibitions are loaded with cultural, aesthetic, social and historical meaning, the strength in Tim Hall's work lies in his suppression of such cultural clutter. Signifiers are excluded from the frame and we are instead presented with landscapes in their purest and rawest form. His photographs are more akin to the history of painting, and indeed it is the minimalist painters whom Hall cites as his inspiration. He provides us with the basic image, but the experience one gets when looking at the photographs is entirely dependent on the viewer. As such, it provides the perfect tonic to Tasveer's other, more culturally complex exhibitions. One should not be fooled by the seeming simplicity of the images however. In fact, the landscape today is an incredibly complex entity and its representation in art poses loaded questions regarding our relationship to the natural world. If in the other exhibitions, the suggestion has been that reading a photograph involves a balanced contract between viewer and viewed, in the work of Tim Hall, this balance is tipped in favour of the audience. We bring to the empty scenes our own set of interpretations, insecurities and meditations. As our relationship to the environment is a continuing point of analysis and debate, the landscape will remain an important and relevant artistic genre.

Magnum Ke Tasveer – at the Movies

Considering the central position of cinema in Indian contemporary culture, the idea of the exhibition, Magnum Ke Tasveer - At the Movies, was to show iconic photographs from Hollywood's golden age, along with images of luminaries from India's own cinematic heritage, such as Marc Riboud's photo of Satyajit Ray. The show therefore constituted a dual education in photography and the history of cinema, whilst for an older generation, it was also an indulgent exercise in nostalgia and a testament to photography's power to evoke the aesthetic essence of a past era. Founded in 1947, Magnum was one of the first cooperative photo agencies. It is known throughout the world for its professional integrity and the impeccable standards of its photographer members. At The Movies was a collaboration between Magnum and Tasveer and it introduced some of Magnum's top photographers, including two of its founding members: David Seymour and Robert Capa. The subject matter in this exhibition was not the brand of social documentary for which Magnum is primarily known. Instead, the lens was mainly turned on the glamour of America's enchanting film industry. Robert Capa is probably the most famous war photographer of all time, for example, but his portrait of Ingrid Bergman shows that he was equally competent photographing Hollywood's elite. As such, the exhibition showed a side to the individual photographers that is not so often seen, and thus formed an interesting take on some the 20th century's most celebrated documentary photographers.

Considering the central position of cinema in Indian contemporary culture, the idea of the exhibition, Magnum Ke Tasveer - At the Movies, was to show iconic photographs from Hollywood's golden age, along with images of luminaries from India's own cinematic heritage, such as Marc Riboud's photo of Satyajit Ray. The show therefore constituted a dual education in photography and the history of cinema, whilst for an older generation, it was also an indulgent exercise in nostalgia and a testament to photography's power to evoke the aesthetic essence of a past era. Founded in 1947, Magnum was one of the first cooperative photo agencies. It is known throughout the world for its professional integrity and the impeccable standards of its photographer members. At The Movies was a collaboration between Magnum and Tasveer and it introduced some of Magnum's top photographers, including two of its founding members: David Seymour and Robert Capa. The subject matter in this exhibition was not the brand of social documentary for which Magnum is primarily known. Instead, the lens was mainly turned on the glamour of America's enchanting film industry. Robert Capa is probably the most famous war photographer of all time, for example, but his portrait of Ingrid Bergman shows that he was equally competent photographing Hollywood's elite. As such, the exhibition showed a side to the individual photographers that is not so often seen, and thus formed an interesting take on some the 20th century's most celebrated documentary photographers.

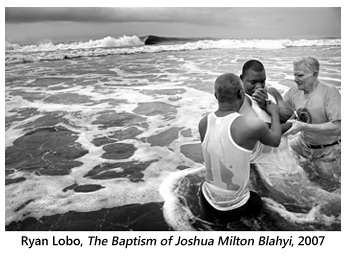

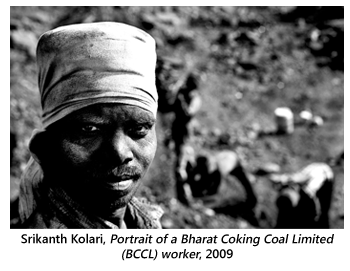

Srikanth Kolari And Ryan Lobo

For Srikanth Kolari and Ryan Lobo, the human story is the central theme of their work. The seemingly innate ability of the photographers to present human issues with such veracity and integrity made these shows very moving in their own different ways. Both Kolari and Lobo attest to the medium's power to tell stories whilst educating an audience on issues outside their immediate towns or cities. We are given a window to peep into other people's lives, and enriched as a result. Kolari's exhibition, Thereafter…, contained three such stories; Jharia, which concentrates on the lives of Indian coal miners in Jharkhand, The Tsunami Coast, which focuses on communities in the Tsunami-stuck region of Tamil Nadu, and Kashmir, a photo story which tackles the prevalent issue of post-traumatic stress and depression in Kashmir. Kolari himself has commented that he does not want to be considered as an artist, but rather as a messenger. He distances himself from irrelevant visual sensationalism in an attempt to give the subject matter more room to breathe. However, one can never fully escape the aesthetic cloak that photography holds over reality, and the photographer's vision will always dictate our interpretations to a certain degree. Accordingly, Kolari's careful compositions give his work purity and balance whilst his choice of dark tones hints at something altogether more melancholic.

Ryan Lobo's images occupy the space between war photography and social documentary. They deal with very real issues as  their subject matter but the questions they raise and the themes they muse upon are universal; war may be the base subject, but in these photographs specifics are marginalized in favour of the more plural themes that are common across humanity. In Liberia, we are confronted with the powerful story of redemption of the former Liberian warlord, Joshua Milton Blahyi. This man was responsible for the death of thousands of individuals during Liberia's First Civil War and Lobo's photographs tell the story of Blahyi's voyage across his formerly terrorized homeland in search of forgiveness from his former victims. A moving narrative is offered whereby exultant scenes of the General's evangelical conversion are juxtaposed with the tormented faces of the families of those whose deaths he was himself responsible. Forgiveness is part of all cultures and religions; by looking at these photographs and considering the story they unmask, we are forced to consider our own capacity for forgiveness, both as it relates to the photographs in question, but also within our own personal histories.

their subject matter but the questions they raise and the themes they muse upon are universal; war may be the base subject, but in these photographs specifics are marginalized in favour of the more plural themes that are common across humanity. In Liberia, we are confronted with the powerful story of redemption of the former Liberian warlord, Joshua Milton Blahyi. This man was responsible for the death of thousands of individuals during Liberia's First Civil War and Lobo's photographs tell the story of Blahyi's voyage across his formerly terrorized homeland in search of forgiveness from his former victims. A moving narrative is offered whereby exultant scenes of the General's evangelical conversion are juxtaposed with the tormented faces of the families of those whose deaths he was himself responsible. Forgiveness is part of all cultures and religions; by looking at these photographs and considering the story they unmask, we are forced to consider our own capacity for forgiveness, both as it relates to the photographs in question, but also within our own personal histories.

The debate as to whether or not photography is art seems redundant in today's more multidisciplinary art world. As Tasveer's exhibition programme demonstrates, photography is not a singular art. Its real interest lies in its ability to extend beyond itself and relate to all aspects of the human condition; both in the context of contemporary art, and in opposition to it. In fact, more than an art form, photography is an educational force, an aide-memoir, a political tool, a historical document and above all, a device that encourages us to ask questions regarding how we document our existence and interpret our surroundings.

Images Courtesy: Tasveer